Courtesy Princeton University Press

Book Review: Up from the Depths: Herman Melville, Lewis Mumford, and Rediscovery in Dark Times, by Aaron Sachs, Princeton University Press, 2022

Herman Melville’s fingers gripped tightly on the cold metal bar keeping him from plummeting deep into the sea. His lookout perch, high atop a whaling ship, provided a perspective on the earth’s watery curvature and much more, into fathoms below and upon the earth’s surface, reflected mysteriously in the glistening waves. His first biographer asserted that the “mariner and mystic” (and the literary renegade) in Melville allowed him to perceive so much that few could understand what he strove for in writing his strange, sea-soaked masterpiece Moby-Dick or, The Whale, in 1851.

The book opened arms to embrace all that a horizon-chasing lookout could see, and beyond. Yet, as time passed, along with the era of wind-propelled whaling, people forgot about Melville despite the mighty, fulminous wake he’d left behind. Until, that is, Raymond Weaver’s 1921 biography of the writer and a fresh dawning upon the profundity, the darkest realities, and beauties the former sailor had wrought.

After a century of more scholarship on Melville than any American writer, Aaron Sachs has found a fresh inlet into his seemingly bottomless depths as an intellectual diver, as a prophet of modern times.

He has done so by reviving a strikingly comparable figure, who helped project Melville’s genius into the 20th century. Lewis Mumford had a view perhaps as high and far as Melville’s, but not as a ship’s lookout. If anything, Mumford’s perspective was urban, say, from the heights of a skyscraper, even if he loved Nature with a passion. He was an urban planner, literary critic, historian, and a social philosopher. The two writers’ intellectual and spiritual connection blossomed in Mumford’s 1929 biography Herman Melville: A Study of his Life and Vision.

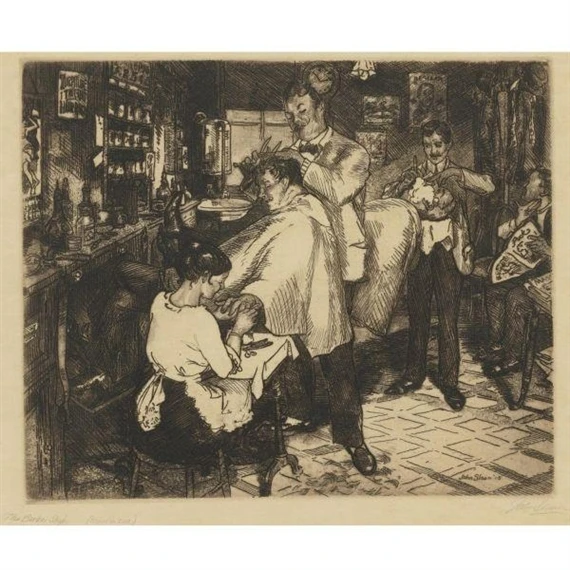

A handsome French edition of Mumford’s biography of Melville. Courtesy librarieforumdulivre.fr

As a Melvillian working on a novel about the man, I have read profusely about him, including a good handful of biographies, most of greater length. But to this day, I can’t say I’ve read one more finely and beautifully attuned to the man and the creative artist than Mumford’s.

In Up from the Depths: Herman Melville, Lewis Mumford, and Rediscovery in Dark Times, Aaron Sachs places the two writers in high biographical counterpoint, in sunlit radiance that illuminates both and, regarding Melville, can stand alongside the brilliant and vast critical and biographical work of F.O. Matthiessen, D.H. Lawrence, Harold Bloom, Sterling Stuckey, Carolyn Karcher, Laurie Robertson-Lorant, Wynn Kelly, C.L.R. James, Leslie Fiedler, Andrew Delbanco, Newton Arvin, Hershel Parker, Elizabeth Hardwick, Robert Penn Warren, and others.

Even aside from his prodigious scholarship and insight, Sachs stands upon painfully familiar grounds. So, we are blessed with fresh historical perspective on two writers courageous and gifted enough to enter the vagaries of American societal quicksand and remain aloft, aside from their periodic neglect.

Sachs alludes to today’s “dark times” when the greatest democracy in history is, as others already have, gravely threatened by an infecting fascist political impulse, that would drag us into the depths of authoritarianism, the opposite of each citizen’s active voice in a diverse society reflecting a global interconnection.

Melville fashioned a microcosm of the United States in the hearty, colorful crew of The Pequod, with the strength in its diversity, yet dared to show how readily they could be swept up in the bloodthirsty madness of eloquently transfixing Captain Ahab, a monomaniac who seized their collective spirit with his demagoguery of a whale, which sent all, save one, to their doom.

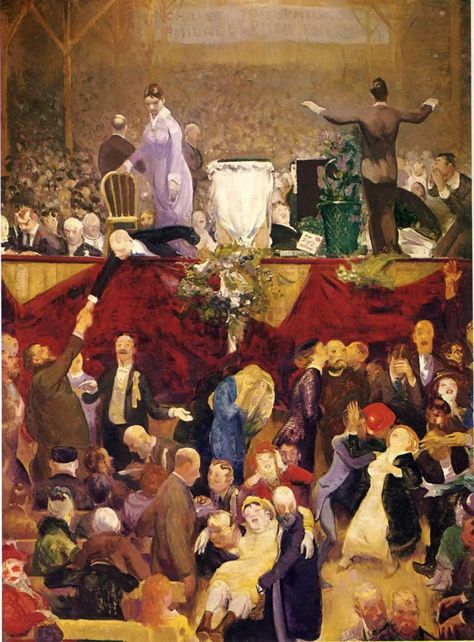

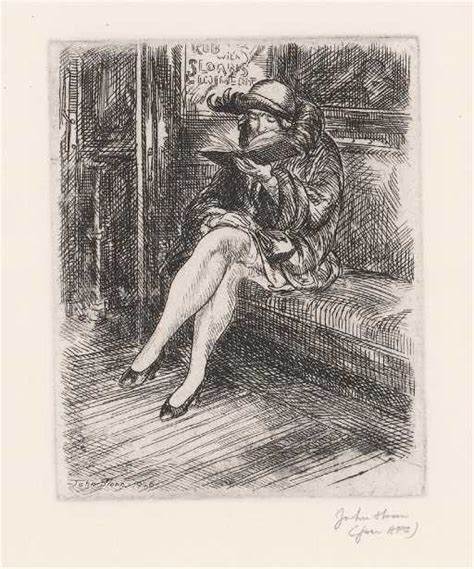

An 1870 portrait of Herman Melville by Joseph Eaton. Courtesy Towleroad Gay News

Whaling was a crucial global industry in mid-19th century, but Melville also deep probed America’s inland by illuminating the social impact of industrialization in the diptych-type short story, “The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids,” from 1855.

“Melville depicted a luxurious gentleman’s club in London and a Berkshire paper factory in which women did all the coarsest jobs,” Sachs writes. “Here, Melville was not only indicting the sacrifice of American manhood to all industrialism, but also echoing one of the themes he developed in (the autobiographical novel) Redburn, about the unconscious dependence of the leisure class on the skilled, competent labor of the scraping-by classes.” 1

Although Melville too-self-critically considered the book a knockoff job, Redburn provides rich ground for Sachs comparative analysis.

“Just as Mumford would several decades later, Melville reconnoitered here what modern cities he had access to, curious about how they shape people’s lives and how they compared to each other. In many ways, they seemed a lot like ships: sites of everyday trauma, often the result of brutally hierarchical relationships – but also sites of cosmopolitan fellowship, where eventually the sustain engagement with difference might help people rediscover a sense of commonality.” 2

Sachs continues, “Melville witnessed the worst kinds of degradation, viciousness, and apathy… people with different backgrounds and cultures…People of different classes and races would almost always be suspicious of each other. But he also saw, in every major city, the concrete possibilities of the great American experiment. At the Liverpool dock, he imagined what each ship might contribute to the United States. Such a vision, he thought, should be enough, ‘in the noble breast,’ to ‘forever extinguish the prejudices of national dislikes. You cannot spill a drop of American blood without spilling the blood of the whole world…Our blood is the blood of the Amazon, made up of a thousand noble currents all pouring into one.’” 3

Such humane and exalted thought renders Melville historically timeless and gives our nation words to live by, even words to love by, the latter a theme Mumford explored deeply.

Some people these days deride such utterances as “nationalism.” That is myopic, ungenerous thinking, especially given Melville’s cosmopolitan worldliness. He maintained a belief in a nation that embraces the world and asserts that the nobility of America’s Democratic experiment has a place in every country and in every heart. Shouldn’t there be reason to at least hope for that? Democracy may not always succeed, perhaps by its nature, but is always there for the offing: “of the people, for the people, and by the people.”

Sachs also does justice to one of Melville’s most underappreciated works, Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War. The collection of often-beautiful, vivid and tough-minded poems assesses and evokes the Civil War experience, from the starkly indelible moment of John Brown’s hanging in “The Portent,” to a long “you-are-there” shadowing of the guerrilla exploits of a renegade Confederate officer in “The Scout Toward Aldie,” to the sublime reverie over a graveyard of fallen soldiers in “Shiloh.” Another, “Ball’s Bluff,” contrasts a town’s patriotic fervor, for its young men marching off to war, against the cold reality: How should they dream that Death in a rosy clime/ Would come to thin their shining throng?/ Youth feels immortal, like the gods sublime.

Melville then added a substantial prose “Supplement” which was intended to soften the poems’ “bitterness.” And, despite Melville’s celebration of American democracy elsewhere in his work, the supplement also looks hard at post-war America.

“Again and again, Melville acknowledged that America had never been Great, that the revolution had produced not a promising democratic republic but rather ‘an Anglo-American empire based upon the systematic degradation of man.’

“And he emphasized that ‘those of us who always abhorred slavery as an atheistic iniquity, gladly we join the exulting chorus of humanity over its downfall.’ ”

“The problem was that some exultant Northerners seemed to take their victory as a sign of moral perfection. To Melville, the fight against slavery was a righteous one but it was ‘superior resources and crushing numbers,’ rather than righteousness, that determined the outcome. Indeed, Northerners had been complicit in the slave system from the beginning, both morally and economically.” 4

“The outcome of the war, Melville realized, had only intensified the scorn and suspicion between whites and Blacks in the South, so if white Northerners were to heap additional scorn and suspicion on white Southerners, the Black Southerners would probably pay the dearest price.”

Melville wrote: “Abstinence (from racial hypocrisy) is as obligatory as considerate care for our unfortunate fellow-men late in bonds.” 5

Melville’s unflinching wisdom foreshadows how Reconstruction would fall apart and lead to Jim Crow, lynching, The KKK, and the ongoing degradation of Black Americans, which continues to this day.

So where do we go from here? As Mumford wrote, and demonstrated through a long, prolific career, only “the perpetual rediscovery and reinterpretation of history” makes true progress possible; when we are actively “rethinking it, reevaluating it, reliving it in the mind,” the past stops controlling us and, in fact, becomes her best tool for “the creation and selection of new potentialities.” 6

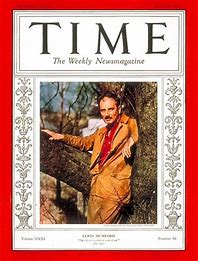

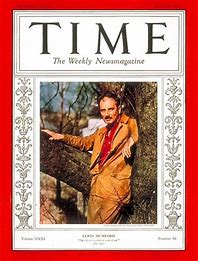

Lewis Mumford made the cover of TIME magazine in April of 1938. Courtesy TIME.

This recalls one of my favorite quotes of the great 19th century American abolitionist Frederick Douglass: “If there is no struggle, there is no progress.”

In 2008, Douglass became another major historical figure deeply compared to Melville in: Frederick Douglass & Herman Melville: Essays in Relation, edited by Robert S. Levine and Samuel Potter. This worthy comparison traverses themes of “literary and cultural geographies,” “manhood and sexuality,” and “civil wars.” Richly recommended, yet far ranging as that book is, Sachs’ is a more enjoyable overall read, given that one author weaves the two writers’ contrapuntal historical dialog into a single narrative, a reading experience enhanced by Sachs’ fluent, often-lyrical writing skills while mining such profound wellsprings of American literature and thought.

One feels it a deeply inspired work in daring to contemplate two great writers a century apart from each other.

One of Mumford’s finest themes draws from Moby-Dick. In the 1950s he was writing in the context of the dangers of the atomic bomb, but the broader resonance remains true.

“The danger we face today was prophetically interpreted a century ago by Herman Melville…Captain Ahab drives the ship’s crew to destruction in a satanic effort to conquer the white whale. Toward that end, as his mad purpose approaches its climax, Ahab has a sudden moment of illumination and says to himself: ‘all my means are sane; my motives and object mad. ’ In some such terms, one may characterize the irrational application of science and technology today. But we have yet to find our moment of self-confrontation and illumination.” 7

What could be truer, when we still struggle to face how much human self-indulgence in science and technology overwhelmingly contributes to climate change, and the precipice we teeter upon, risking Earth’s survival as a livable planet?

Both Melville and Mumford were Jeremiahs in the best sense. Indeed, Sachs ends his book in their righteous spirit, exhorting readers beyond mere contemplation of all that these great writers presented.

“Can democracy offset the looming trauma of climate change, with its inherent threat to our sense of continuity?” Sachs asks. “Only, Mumford would say, if it’s a fully inclusive democracy that fosters gratitude and sacrifice, only if democratic participation involves embracing all ‘the small life-promoting occasions for love,’ as Mumford put it in 1951, after two decades of work on The Renewal of Life.

“We need to make lifebuoys for each other, whether in the form of international treaties, or social welfare programs, or offers of shelter, or poems for our children. We need to reach across every form of difference: only a less-traumatized, less-divided citizenry will be able to replace carboniferous capitalism.” 8

Up from the depths, the bloodshot eyes of Melville and Mumford would see no less.

___________

1 Aaron Sachs, Up from the Depths: Herman Melville, Lewis Mumford, and Rediscovery in Dark Times, Princeton, 2022, 145

2 Sachs, Up from the Depths, 147

3 Sachs, Up from the Depths, 153

4 Sachs, Up from the Depths, 24

5 Sachs, Up from the Depths, 25

6 Sachs, Up from the Depths, 222

7 Sachs, Up from the Depths, 295

8 Sachs, Up from the Depths, 360

Like this:

Like Loading...