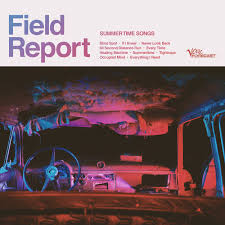

Field Report Summertime Songs (Verve Forecast)

The waning days of summer feel like a perfect time to consider what lies in the warm shadows of Field Report’s latest album Summertime Songs, released last March. Yes, days remain sultry and summertime songs glow and gleam with all the embracing life-force of the season.

Yet singer-songwriter Christopher Porterfield’s senses arise from nature’s passing cycles into death, and the quietly troubling and deeply philosophical musings of his dream-infested brain.

You feel older and wiser after it’s done, even as you sing yourself the ear worms of Porterfield vocal hooks like an enchanted teenager. Yes, it sounds slicker than anything he’s ever done, but it’s also easily as deep, beneath the pop gloss. The effectiveness arises first from the gentle experimentalism of his music, which has abdicated the lead guitar, as has much of contemporary pop, so refreshing a release from testosterone-fueled ego and excess. That’s not to knock the all the great guitarists and moments by guitarist of varying repute, but time has passed, and Field Report is right there, right here.

The album opens with a searing electric violin vamp that sounds like Steve Reich on steroids and immediately pries open the listener’s imagination. Throughout the album, the setting is expansive yet vivid in textures of synthesizers and electronic strings, and the sinuously propulsive drum grooves of jazz drummer Devin Drobka, delighting in messing with rocky back-beat jollies. But ultimately this is about the poetry of Porterfield, and his voice’s soulful declamation of it, by turns ardently striving and biting the tongue of its own querulous spirit. His eyes and senses are too wide-open to be bullish about anything, even though they love humanity in loss, of ongoing glory that summer blesses us with.

How is he doing chart wise? Well, the album may have risen and peaked already but it is listed on EuroAmericana chart the among the “Tips” albums by the chart’s resident critics. http://www.euroamericanachart.eu/. Nor has the album to date apparently caught up with the charms of the group’s first two albums, according to lastfm.com: https://www.last.fm/music/Field+Report

Porterfield remains a sort of songwriters-songwriter, having won over a number of grade-A songcrafters whom he or Field Report has opened for, including Emmylou Harris, Richard Thompson, Adam Duritz and Counting Crows, and Aimee Mann.

This cognitive dissonance in the music market may be partly because Summertime Songs is perhaps a little too streamlined in sound for the more rough textures that appeal to typical Americana music listeners. Nevertheless, Porterfield remains decidedly the sort of ruminative, deeply resonant singer-songwriter that many folk music lovers cherish. So they’re missing something if they overlook this. And there’s something quintessentially American about his point of view as well, even as the electronics seem to borrow something from EuroPop.

Christopher Porterfield of Field Report. Courtesy NPR

What’s American about this album? First, the band’s from Milwaukee, arguably the capital of the nation’s heartland. It also involves the individualism of Porterfield’s questing. He also often performs solo with only his acoustic guitar, and as big-sounding as his anthemic songs are, they work quite well solo, given the strength of his voice, musicality and poetry. He reflects today’s America especially in his ongoing striving to get a grip on truth and reality, while both seem to flirt with dreamlike states, poisoned improbabilities and living nightmares – especially when so many ordinary Americans suffer from addictions, to opioids or demagoguery’s easy, manipulative answers.

You were bouncing off the guard rail shouting at the wind

We were off our meds, drinking again;

we played them like a stolen violin

I knew my outlines and my ends,

They were embarrassed by sincerity back then.

If I knew/ what I know/ so far yet to go

The careening scene from the song “If I Knew” feels as classic Americana as Kerouac’s “On the Road,” evoked also in the album cover’s shambling car interior. And the last triplicate phrase, with its ending twist, reveals a guy gripping a few hard-won wisdoms. Yet the strongest of these is having learned a few forward steps in a still-long journey. The last phrase is the song’s resounding refrain, hollered in the roaring wind. Those who mock sincerity with currently-fashionable cynicism end up on the sidelines of complacency.

Field Report performs “If I Knew” from the album “Summertime Songs.”

The next song, “Never Look Back” sustains Porterfield’s questing theme with fresh insight. He sings of trusting someone to cut off his hair with a pocketknife “…with my eyes closed I don’t need you do try.

I just need you to know I’ve earned what I’ve been going (through? A word lost in the wind?) and I am all about the day when we cut it all off, and throw it all away.

Turn the telescope back around; get these troubles out of view. Forgiveness does not excuse, it just prevents all of the others from destroying you.

The haircut is really a metaphor. You really sense the speaker’s relationship to humanity, still a Melvillian isolato, a bit ravaged, deeply troubled, yet embracing forgiveness as a kind of shield or scab. Bleeding may ensue, as well as backsliding.

From the video of the band performing from the new album, it appears Porterfield still waits for someone to hack off a shock of hair that resembles Elvis with a finger in a socket. But it’s the meaning behind the liberating act sustaining him, not the promise of short hair, per se.

So here’s a man who wears his flaws on his sleeve, or his scalp, and never stops digging into the querulous uncertainties that awaken him restlessly each morning. And his throat clears to the voice of an everyman, with a heart big enough to let his lungs bellow out like schooner sails catching the wind.

Christopher Porterfield is the sort of seer-poet who can sustain us if we give him a chance. Late summer’s not a moment too soon. He won’t always provide comfort but he’ll give us a boost, so we can see the horizon, even with the baleful sun, or inner demons, in our face.

_______

“Summertime Songs” album cover courtesy NoDepression.com