“Watching Americans Watch Parades.” Lebanon, Kentucky, September 24, 2016. Photo courtesy theatlantic.com Photo by George Georgiou

The times, they are a changin’ yet, and what goes around comes around, treading over the blood and tears on the tracks, the ravaged hearts struggling on.

The Atlantic remains required reading for anyone with an open and inquiring mind about culture, politics and the world, regardless of your persuasion. The November/December issue How to Stop a Civil War might’ve been transported to the publication’s earliest years as an abolitionist publication. What might’ve happened? You unlock this door with the key of imagination, as Rod Serling would say. Times are more complicated but the conflicting dynamics, especially on race and “the Other,” is not much different.

Since then the magazine has evolved into a sometimes exquisitely-balanced — sometimes walking a tightrope — but morally inquisitive and rigorous publication without such a clear agenda.

The November 1857 Atlantic Monthly (left), a voice born in a time of crisis on the verge of The Civil War, and the current magazine and app. Courtesy the atlantic.com. Cover art of December 2019 issue by Sam Kaplan, Brian Byrne and Atlantic creative and art directors.

Look at the December issue’s cover, beside the debut 1857 issue. A pejorative adjective comes to mind with this bleeding image. On second thought, in such times this cover speaks powerfully to painfully melodramatic times. That’s the adjective. But the cover with the new bold but elegant but assertive “A” logo reflects courage and resolve in our time of crisis, as is the sum part of the issue’s theme articles. The mag’s art and creative directors see the startling hand image as a metaphor for a “body divided against itself,” deftly echoing Lincoln.

Introducing the edition, editor-in-chief Jeffrey Goldberg delineates some connections and distinctions with great urgency in the opening salvo for peace if not necessarily civility (more on that later) “A Nation Coming Apart,” by referencing the magazine’s debut issue.

But it showed how measured and penetrating the publication can be in its range of reporting.

How far do they cover the stormy waterfront?

The first of three thematic sections of the main body of the issue is titled “How to Stop a Civil War.” They set a provocative edge in one of the first pieces, an interview-feature on Daniel Miller, leader of the Texas secessionist movement on among the most mot intellectually stimulating right-wingers around. Union stalwart-angel Abe Lincoln would shudder, of course. I loved a brief, delightfully insightful photo essay (more a diptych mural, really) by George Georgiou Watching Americans Watch Parades. (See top photo)

Yoni Appelbaum’s edge-of-dystopia piece “How America Ends” follows his recent cover story which helped spur the intellectual charge to impeach Trump.

His historical perspective reaching into the Civil War legacy brought to mind a great novel a read and reviewed, Cloudsplitter the extraordinarily personal-yet-big-picture story of radical abolitionist John Brown, narrated by his son, and written by the gifted and inspired Russell Banks.

Yet the issue is also very to-the-media-and-cultural moment. Don’t miss “Why it Feels Like Everything is Going Haywire,” a social-media “conversation-essay” by Jonathan Haidt and Tobias Rose-Stockwell, with a powerful big-picture perspective.

Then there “Too Much Democracy is Bad for Democracy” by Jonathan Rauch and Ray La Raja (illustrated above by Ilya Milstein), which indicts our democracy primary election system but doesn’t rail against the Electoral College, which seemed an oversight. They argue for returning to a system of relying more on knowledgeable party experts, in the proverbial back rooms. Elsewhere, conservative columnist David Frum does address the Electoral College dilemma by asserting that a second Trump term, with a Republican Senate majority involves a deliberative body that’s “less democratically representative than the Electoral College,” in “When Trump Goes.”

Part 2 of the issue is titled “Appeals to our Better Nature”

The very meaty and challenging section is anchored by “The Road to Serfdom: How Americans can Become Citizens Again,” by Danielle Allen. “Can This Marriage be Saved?” examines an effort at applying couples-counseling technique to red and blue state group participants.

Part 3 is titled “Reconciliation and its Alternatives”

In “The Enemy Within: What Principles of Democracy Must Citizens Live By?” recent Secretary of Defense James Mattis boldly declares: “Cynicism is cowardice. And cynicism is corrosive when in it saturates society, as it has saturated much of ours.”

As thought-provoking as any piece is “Against Reconciliation,’ by Adam Serwer, which argues the dangers of a political middle acceding to those who would exploit America only further. He says the gravest danger to American democracy isn’t an excess of vitriol—it’s the false compromise of civility. Serwer likens the current state of American politics to the Reconstruction era, “when the comforts of comity were privileged over the work of building a multiracial democracy.” He argues that the illusion of peace and civility is often purchased at the expense of true progress. “The danger of our own political moment is not that Americans will again descend into a bloody conflagration. It is that the fundamental rights of marginalized people will again become bargaining chips political leaders trade for an empty reconciliation.”

Finally don’t miss “What Art Can Do: The Power of Stories that are Unshakably True,” by Lin-Manuel-Miranda, creator of the Broadway masterwork, Hamilton.

Buttressing the Americana photo diptych is an essay on the great American gritty verite photographer Gary Winogrand, “A Street Full of Splendid Strangers.”

You begin to sense how brilliantly and carefully this issue was conceived and realized.

For what it’s worth, I’ve done nominating for the Pulitzer Prize a few times (in music) and was leader writer of a Pulitzer-nominated group project, and this issue is surely a powerful candidate for the coveted prize, in some group-project category.

That’s not even counting the culture review and feature pieces, which only strengthen the issue. See reviews of Margaret Atwood’s sequel of sorts to A Handmaid’s Tale, and of Martin Scorcese’s autumnal new American gangster film, The Irishman. A Q & A with first-time director Director Melina Matsoukas on her Queen & Slim, a “black Bonnie & Clyde film” starring Daniel Kaluuya, (Black Panther, Get Out) and Jodie-Turner Smith. “I wanted to showcase black love, and unity, not just romantic love. Black unity is the greatest power against oppression, Matsoukas says.

David Blight also offers a mediation titled “The Possibility of America: Frederick Douglass’s Most Sanguine Vision of a Pluralist National Rebirth,” drawing from his 2018 Pulitzer Prize-winning biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.” The black social and civil rights pioneer was also original a prophet of struggle fomenting progress.

Here’s a link to The Atlantic’s December issue: “How to Stop a Civil War.” https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/toc/2019/12/

Which leads me back to Banks’ 1998 novel Cloudsplitter, (a finalist for the Pulitzer and PEN/Faulkner Awards) and all we might gain from reflecting on the extreme socio-political dynamic that inspired Brown to such drastic measures as murder, for the sake of finally freeing black slaves.

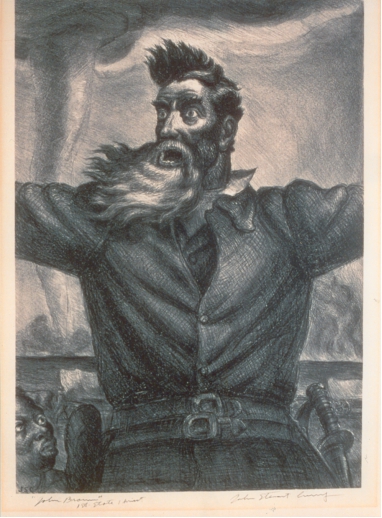

Radical abolitionist John Brown on the verge of splitting clouds, and America, with his zealous lightning strikes. Print by John Steuart Curry.

He remains a controversial figure. When I mentioned I was reviewing this book to John Patrick Hunter, a progressive political icon at The Capital Times, Hunter immediately declared, “He was a hero!” His spouse Merry, standing beside him, softly shook her head. “Killing people, I have problems with that,” she said.

Lincoln, of course, saw the ensuing conflagration as the crucible to preserve the Union, just as much as slave liberation. To me, the book’s story feels unshakeably true, and burning a brand of passion into our times. Cloudsplitter is a long but rewarding and psychologically fascinating novel. So read my review and do consider reading the book, as a profound message to the groaning pain of our changin’ times:

| THE CAPITAL TIMES

Friday, May 1, 1998

Edition: All

Section: Editorial

Page: 13A

Source: By Kevin Lynch

Type: Review

Memo: Kevin Lynch was an arts writer for The Capital Times. |

ABOLITIONIST’S STORY IS AS DANGEROUS AS AMERICA

Russell Banks’ majestically sad and impassioned novel about the abolitionist John Brown is a great and inspiring book. It is also dangerous, in the way that America is perilous and contradictory in its ever-shifting bedrock of independence for all people, rife with subtle and vile abuses.

The danger factor has been glossed over or ignored by critics who have been tossing deservedly glowing literary laurels at the feet of Banks.

I suspect the author would kick those politely aside, to search out responses from ordinary, deep-rooted Americans, descendants of slaves or of Civil War fighters, or any lovers of freedom and equality.

When he finished his last novel, “Rule of the Bone” about a teenage runaway, Banks did more than tour the tony bookstore circuit. He went to urban high schools to discuss its implications with students.

That, too, was a somewhat dangerous book, if one saw it as simply glorifying Bone’s rambling, delinquent lifestyle.

Now “Cloudsplitter” might be seized as an argument and excuse for terrorism. While copiously researched, it creatively humanizes the radical whose acts of carnage in the name of God and freedom brought this nation to the brink of the Civil War.

But John Brown’s vision of freedom still burns at the core of America’s best ideals, even if his Bible-based philosophizing and fiery charisma suggest cultism. The story’s narrator, Brown’s son Owen, convincingly recounts how, in growing to manhood, he fell increasingly in thrall to his father.

Early on, Brown’s family is stunned into clarity when he reads aloud scores of shameless “missing property” notices: “Runaway, a negro man named Henry, his left eye out, some scars from a dirk on and under his left arm, and much scarred with the whip” . . . “I burnt her with a hot iron on the left side of her face; I tried to make the letter M.”

As the voices of father and son alternate, the unthinkable need for their radical violence seems a matter of historic necessity.

The new western territories of the 1850s appear to be on the verge of becoming slavery states. The balance of power is clearly tipping toward the South’s political position. The reactionary Fugitive Slave Act has enabled the whim of any Northern white to deliver escaped slaves — or any freedman — back to Southern plantations. The president is Franklin Pierce, an unspoken sympathizer with slavery.

Banks’ storytelling builds a rumbling suspense, like a slowly rising earthquake, opening the cracks of the nation’s horrid moral crisis.

John Brown is an inept businessman, but he has a strangely burning brilliance as a radical abolitionist. His strategies grow from analyzing military battles and maxims in the Bible and by traveling to Waterloo to understand Napoleon’s mistakes. When the violent, racist hordes called the Border Ruffians appear to take control of Kansas, Brown and his rag-tag bunch of sons and followers respond with their shocking guerrilla counterattack, in Pottawatamie, Kan. Would it be enough to spur action from the seemingly passive Northern abolitionists?

Unlike the rhetoric of many right-wing militia types, this story is not about craven self-interest masquerading as patriotism. It is not about people lusting to possess AK-47s, to assert the “right” to act out their worst bigotry and paranoia.

John Brown’s life mission to deliver America’s blacks from slavery reveals him as the most fearless liberal of all, priming for “the revolution we should have fought back in ’76!” as he tells Frederick Douglass, the great black abolitionist.

Douglass ironically notes that the British “have outlawed slavery for close to a quarter of a century now.”

Many reasonable people understandably see a madman in John Steuart Curry’s famous portrait of Brown. He was grandiose, flawed and deluded about what he could accomplish. But this preacher’s religious fervor did not harbor political ambition — only the affirmation that the nation’s soul would be saved by the death of slavery.

As Banks tells it, no other American had Brown’s boldness of vision, not even Douglass, who tried to discourage Brown from his ill-fated raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Va., in 1859.

This novel moves with the emotional restlessness of a family and a nation just awakening to the need, finally, for a bloodletting, and a long, harsh, self-defining victory over its demons.

Among a spate of strong secondary characters, two are unforgettable — Brown’s freed-slave compatriot Lyman Epps and Owen’s simple, pure younger brother Fred — whose fates spur the story’s motion as clearly as any political act. They give the novel gut-wrenching human dimensions that Banks has now mastered over his 12 works of fiction. (Filmmakers are finally grappling with his dramatic potential, with “The Sweet Hereafter” and the upcoming “Affliction.”)

As with “Affliction,” Banks fearlessly looks at the violent instincts coursing through blood ties.

“Cloudsplitter” is the name of an Adirondack peak that symbolizes his father for Owen. This novel stands just as massive, shadowed and unshakable. That is why it transcends terrorist cant. It is rigorous moral fiction, examining its lead characters’ motives and actions from all possible angles, finding epic heroism and life-haunting fault, especially in Owen himself.

This John Brown is a caring father and husband and “regardless of their race or station, he pointedly treats women as equal to himself,” Owen writes.

His father only lords over others about slavery, the son explains. “To Father, white and black Americans alike were bound by slavery: the physical condition of the enslaved, he insisted, was the moral condition of the free.”

It is Owen who dwells in the blood-lusting darkness of the Brown family’s worst impulses. He long ago lost his faith, which remains the fundamental difference between him and his father.

Now, many years after the debacle of Harpers Ferry, he agonizes that his spiritual void contains a root of his violence, betrayal and cowardice.

He was the sole survivor.

This feels like the masterpiece of a writer who matters like few others today. “Cloudsplitter” conveys the sweep of a mighty land and the historic weight of Owen’s burdens. It reads as a private confession with an inexorable, gravitational pull.

One arrives at the end as if waking from a long dream of America, risen from the nation’s subconscious. Owen and John Brown are archetypal men one may grow to love and perhaps fear, as does a son for a great, dominant father.

As one grows to love and perhaps fear America itself, with its astonishing freedoms, its shifting moral ground and its devastating power.

________________

Like this:

Like Loading...

Packer kick returner-runner-receiver Tyler Ervin. courtesy Getty Images

Packer kick returner-runner-receiver Tyler Ervin. courtesy Getty Images