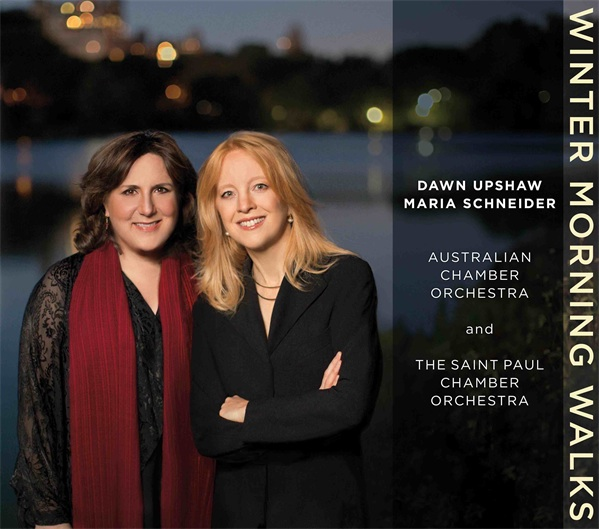

Composer Maria Schneider conducts a concert performance from her new album of chamber orchestra music, Winter Morning Walks. Courtesy leelowenfishbooktrib.com

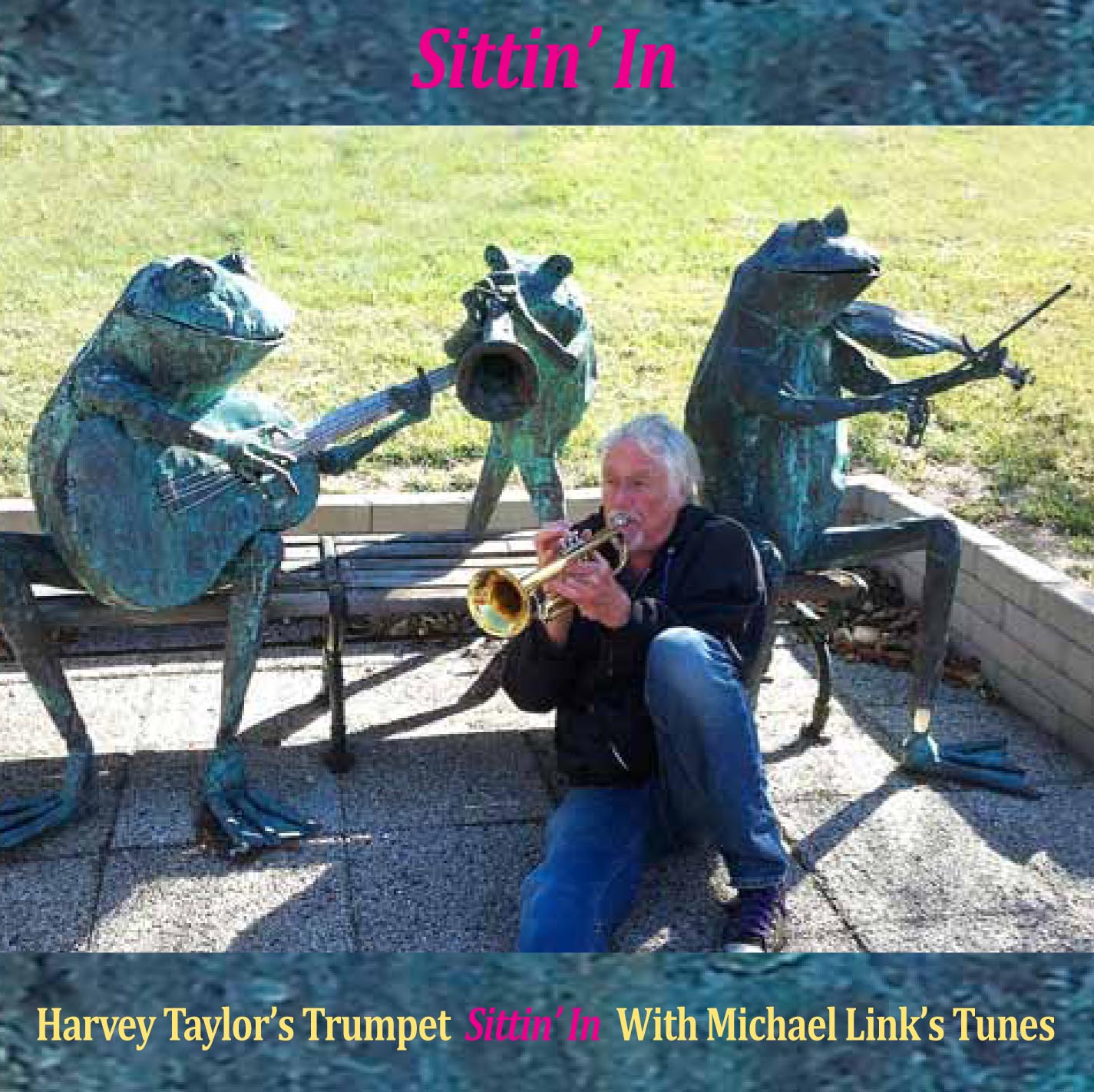

Winter Morning Walks Maria Schneider/Dawn Upshaw/ The Australian Chamber Orchestra/ The St. Paul Chamber Orchestra (ArtistShare)

The most beautiful sound in all the world…Maria’s. So Leonard Bernstein might’ve commented on how our finest jazz orchestra composer attains comparable artistry with a chamber orchestra. Setting two groups of poems, Schneider catches the wings of soprano Dawn Upshaw, whose singing swells and soars with a deep-hearted glow. Ted Kooser’s winter poems tip-toe with Frost-like reflection, which Schneider wraps exquisitely in crystalline yet wind-supple gestures. It’s gorgeous stuff, yet Schneider fragments her flow when needed, and smartly contrasts Kooser’s wide-eyed wonder with Carlos Drummond’s knowingly droll verse, including “Quadrille,” a wry meditation on unrequited love’s cruel turns.

Despite the CD’s titular theme which evokes the “bone-cracking cold” of a perfect solstice morning, Schneider again displays a melting lyricism. That quality distinguishes her from most of her jazz orchestra contemporaries and may be rooted in her classical training at the University of Minnesota, which predated her jazz schooling at Eastman School of Music. For example, there’s the stylistic manner of periodically repeating the poet’s line in the score for the singer to double up on. This commonplace of art song helps honor inspirations and allows felicitous variations of phrasing.

Schneider has long mastered a floating rubato pace rare among jazz composers typically dependent on a measure of rhythmic matrix or pulse. This allows her to daub and dash her orchestral palette with a vivid array of colors which often evoke mentor Gil Evans as much as any contemporary classic composer. A recent New York Times article recounts her trying to re-orchestrate an Evans piece at the request of the great arranger-composer, who is best known for his triumphs with Miles Davis.

“I was in my 20s and felt completely out of my league,” Schneider recalled. “One day I came in with what I wrote and (Evans) was horrified. He said: ‘No, no, no. I want those low instruments at the top of the range so they’re uncomfortable. And these high instruments at the bottom of their range.’ He wanted people playing completely at the opposite range at struggling points in the music. And then it was just, My God, that’s the stuff you can’t learn.” 1

But you hear Evans-esque sorcery in her new music. Schneider inserts atonal passages with prudence and purpose, as in “Our Finch Feeder” which sonically mimics the hustle-bustle of hungry birds.

Her die-hard jazz fans may miss the improvised solos she garlands her more familiar works with. The new key here is soprano Upshaw, a master of contemporary classical music but not a jazz singer. Like much of Schneider’s recent jazz music, this is virtually all through-composed, even though three of her jazz mates (pianist Frank Kimbrough, bassist Jay Anderson and clarinetist/bass clarinetist Scott Robinson) play in portions.

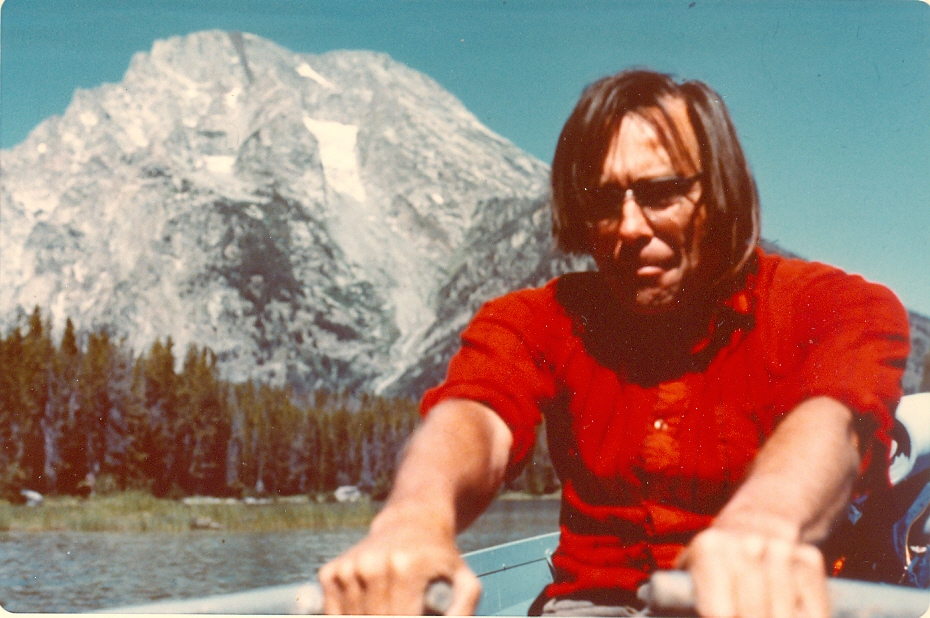

Soprano Dawn Upshaw (left) with composer-conductor Maria Schneider. Courtesy minnesota.publicradio.org.

And yet a vocal passage like the prologue for Drummond’s De Anrade Stories has a lilting air reminiscent of passages she’s concocted for jazz singer Luciana Souza, as on Schneider’s Emmy-winning “Cerulean Skies” from Sky Blue. Unsurprisingly, Upshaw handles this textually abstract passage with aviary splendor. She’s one of the best reasons for people to hear the new CD, having become a sort of crossover star due to the deep, accessible humanity of her singing and the catholicity of her tastes. She had become a Schneider fan and approached the composer about this project.

It’s a chance for such listeners to expand their horizon just as it is for classical fans who’ve never heard the likes Schneider. This recording is recommended to anyone who loves good music regardless of categorical appendage.

Ms. Schneider’s personal point of view is worth considering. I read about the new CD in The New York Times Sunday Magazine. 2 As Zachary Woolfe wrote, “Schneider still lives in the same cozy one-bedroom on the Upper West Side that she hauled music stands to and from all those years ago.”

CD cover courtesy mariaschneider.com

I’m hardly a high-profile music critic. Yet I received a copy of Ms. Schneider’s CD (via ace publicist Ann Braithwaite) within a week of the article, directly from the composer in the mail. Woolf characterizes Schneider as “prone to insecurity.” If so, this is complemented by remarkable courage. As a woman, she’s forged a currently unparalleled career in a still male-dominated jazz field. Her label ArtistShare, which she co-founded, pioneered the ambitious DIY concept of fan-financed recordings. But I wonder if her “insecurities” also reflect a gender difference, having to do with ego and humility. Schneider defers to Upshaw for top billing on the CD cover. Though many jazz bandleaders (including Evans) have performed technically limited “arranger’s piano,” Schneider never plays piano in public. Her sensibility also suggests a consistently humble Midwesterner’s experience of nature.

There’s also a celebratory rapture in this pastoral music that is characteristic Schneider and, it seems to me, an always-precious commodity in such spirit-deflating times as ours.

If she’s risking a wintry tightrope walk over her jazz success, her skills are as surefooted as a hardy north woodsman’s.

________________

A shorter version of this article was published in The Shepherd Express.

1 The New York Times Sunday Magazine, April 13, p. 22

2 Ibid p. 20

The Artist and his Mother Arshile Gorky, oil, 1926–36 Courtesy calitrev.com

The Artist and his Mother Arshile Gorky, oil, 1926–36 Courtesy calitrev.com