Pianist Geoff Keezer and vocalist Gillian Margot at Blu nightclub in Milwaukee Saturday. Photo by Mark Davis

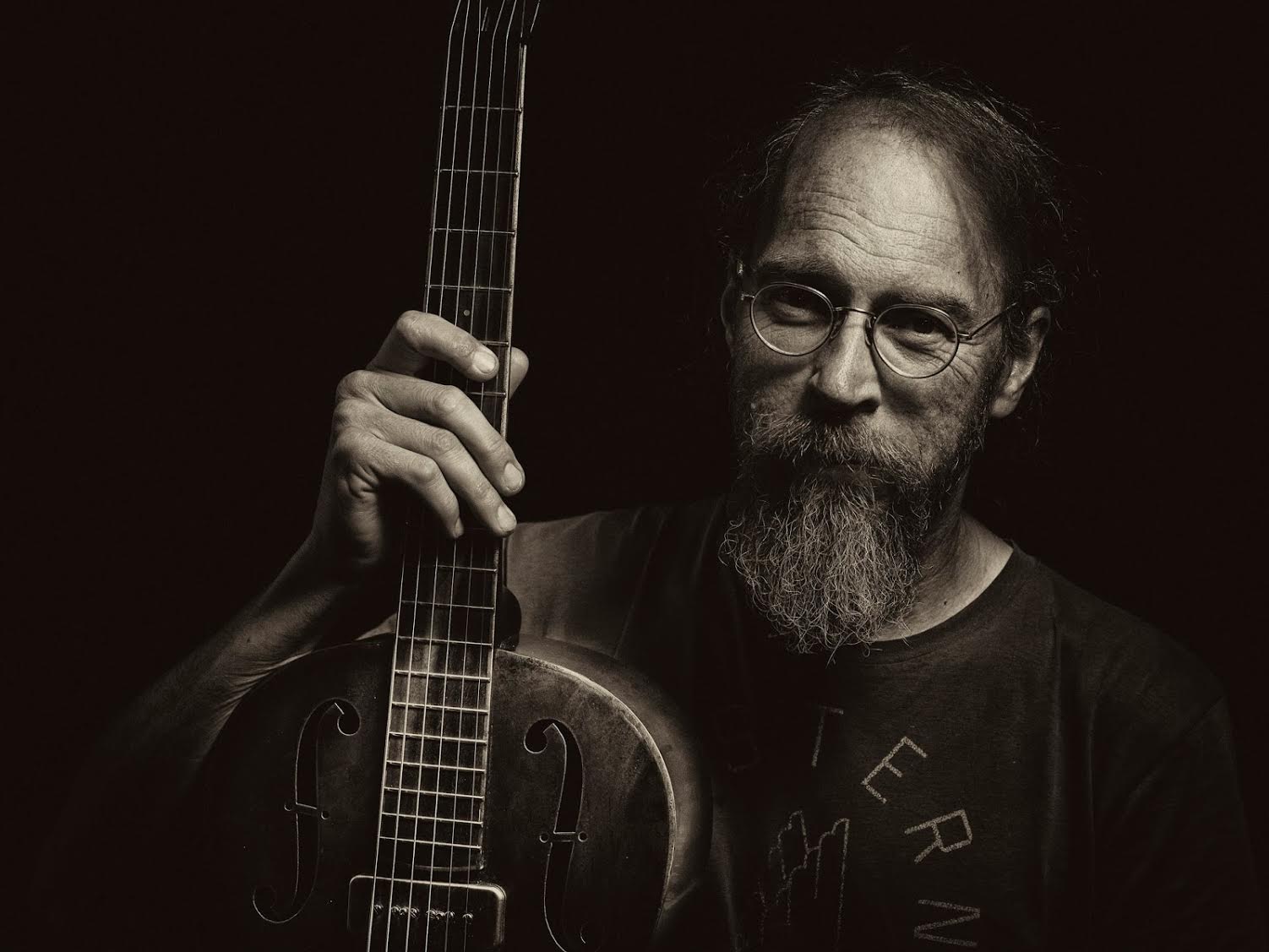

“Death don’t have no mercy in this land.” — Rev. Gary Davis

Saturday night I finally caught up with pianist Geoff Keezer again, and it’s sad that it took this long for me, due partly to over a decade of my very unsettled existence. But I think it’s also a comment on the state of jazz as a still-neglected if indomitable art form.

I had attended a convivial, if rain-swept, early-evening block party in my North River West Milwaukee neighborhood, so my girlfriend Ann and I had to change our cloths, and dry out. So we got to the Pfister Hotel’s 23rd-story nightclub Blu too late to get seats to appreciably hear and see Keezer.

But it was Saturday night at the high-altitude downtown hot spot and Keezer (and his talented current touring partner, vocalist Gillian Margot, who I can’t do justice to here) have enough of a rep to get an SRO crowd in their two-night stay.

We did have an expansive and romantic nocturnal view of Milwaukee’s Lake Michigan shoreline, with the music only fitfully filtering back, enough to hear Keezer’s ingenious adaptation of Peter Gabriel’s “Come Talk to Me.” The pianist’s irrepressibly affirmative performance of the song (here) beats back the night that The Grim Reaper always hopes to mercilessly claim again. Human connection perseveres.

Then a friendly but chatty conventioneer and outboard motor collector sat down in our far-flung corner and, for our ears, Keezer’s second set drowned in a flurry of motorboat memories, and the flotsam and jetsam left in its wake.

Water-logged once again (figuratively this time) and no closer to a better seat, we left before the end of the third set. But after the second set, I did get a chance to catch up with Keezer personally though we’d never actually met. I’d begun following his career since his earliest auspicious recordings on Columbia DIW. He played as the last pianist – with another Wisconsinite, trumpeter Brian Lynch – in the last edition of Art Blakey and Jazz Messengers, including the band’s final recording One for All, months before the firebrand drummer-bandleader’s death in 1990.

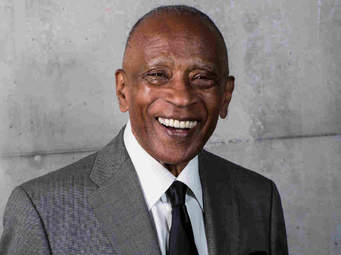

And that brings me to a theme of this column, the death of jazz musicians, including recently passed vibist Bobby Hutcherson. Though it’s hardly the death of the vernacular and art form, as musicians like Keezer, Lynch (no relation to the writer) and thousands of others prove daily.

Keezer, is from Eau Claire, Wisconsin, which naturally piqued this Badger-state native’s interest when he first came to my attention in the early ’90s. There may be no better pianist to come out of Wisconsin. As David Velleman, a YouTube commentor, noted recently to Keezer: “A lot of piano players from WI Lynne Ariele, Ethan Iverson, Melvin Rhyne, (David) Hazeltine, Dan Nimmer, Jon Weber, etc. I think you and maybe Hiromi are the only pianists on earth who can play that Chromatic to Diminished to whole tone (all scales) (or that set of set of tones you heard.)…You the man!”

Last Saturday, when I bought a CD from Keezer and introduced myself to him, a few more things came to light.

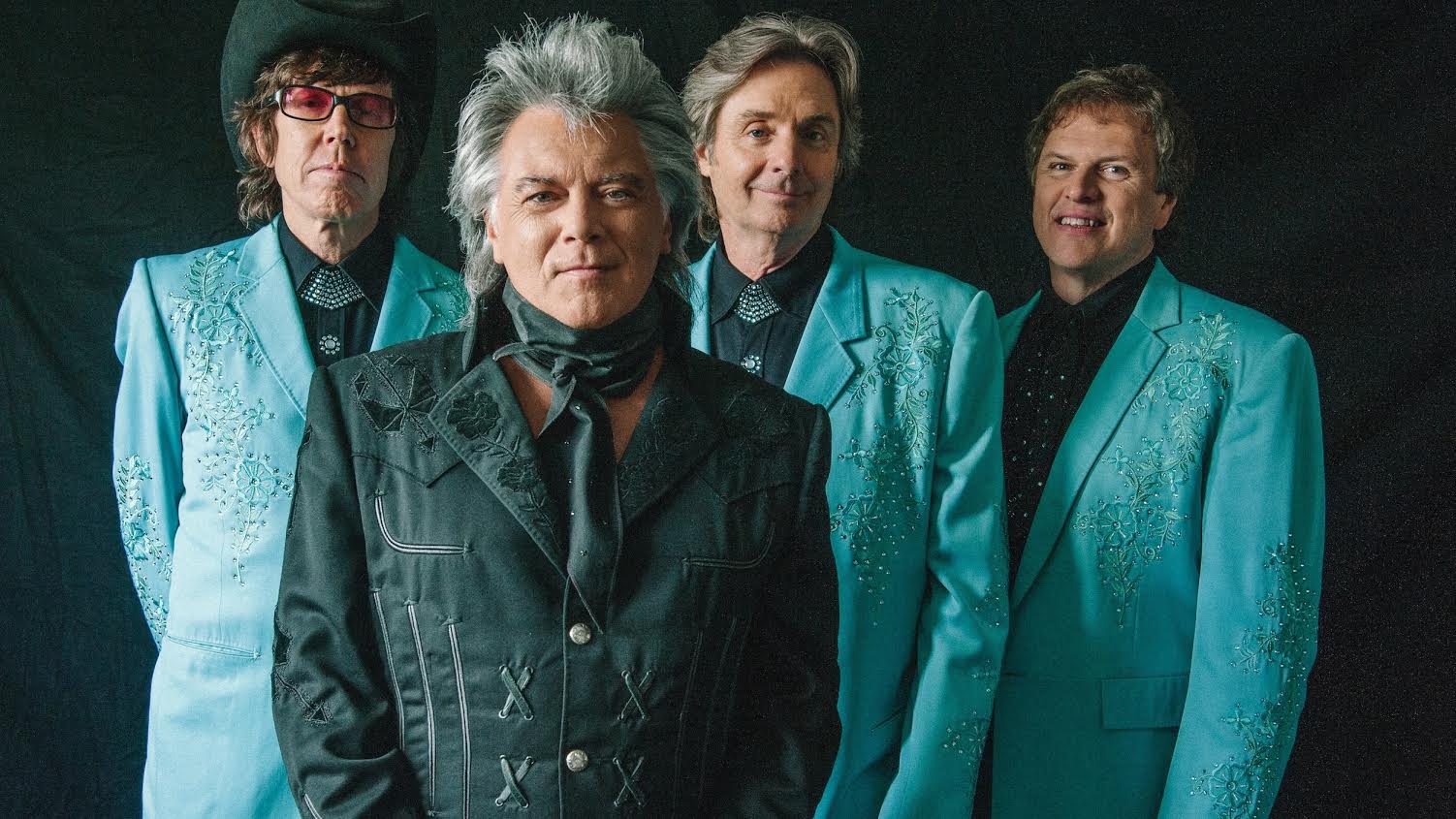

I told him that I had last seen him as a member of the fairly audacious and visionary group The Contemporary Piano Ensemble, which toured across the country in the mid-1990s.

I told Keezer of the remarkable phenomenon of seeing these four great jazz pianists — Keezer, band founder James Williams, Mulgrew Miller and Harold Mabern — playing four grand pianos with bassist Christian McBride and drummer Tony Reedus. And that this had happened outdoors at the zoo, in Racine, of all places. I’d gone down to the Racine Zoo to hear the ensemble with a dear friend Jim Glynn, a popular disk-jockey on WMSE and amateur jazz-improv drummer and flutist who (thematic strains again) died before his time, in 2004.

Keezer recalled the concert but then admitted that he never realized he was playing at a zoo. The facility’s aesthetics and humane discretion had set aside a park-like setting with bandstand for its concert series. So it created a natural physical and acoustic cocoon from the zoo itself, probably so animals would not be unduly disturbed.

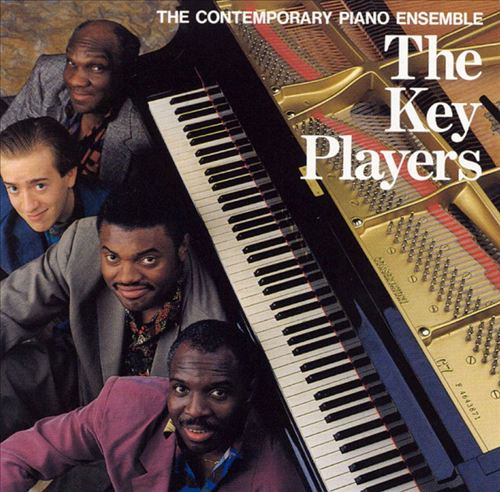

The CPE recorded only two albums, Four Pianos for Phineas, a tribute to pianist Phineas Newborn on Evidence, and The Key Players on Columbia DIW in 1993 (ex-Jazz Messenger pianist Donald Brown would sub on a few tunes, and on tour.)

Cover of “The Key Players” on Columbia DIW. Courtesy allmusic.com (top to bottom, Harold Mabern, Geoff Keezer, Mulgrew Miller, James Williams.)

Cover of “The Key Players” on Columbia DIW. Courtesy allmusic.com (top to bottom, Harold Mabern, Geoff Keezer, Mulgrew Miller, James Williams.)

But the Contemporary Piano Ensemble managed to be both straight-ahead and cutting-edge at the same time. Their repertoire of both standards and originals proved compelling and, in their eight piano hands, captivating and sometimes head-spinning. They rarely sounded gimmicky and, like the sort of “witch-doctor” Art Blakey could invoke, these musicians could shake, entrance and transform you. But they never felt like the musician-doctors who dole out medicine for the confused and weary patient, as some self-justifying improv music does.

Most amazingly, they rarely got in the way of each other, a sign of deep mutual respect of each other and their material. Here’s an example of that from The Key Players, as they play Miller’s “One’s Own Room.”

Carrying four grand pianos on tour must’ve been a bit like Hannibal leading his elephant-driven army over the mountains, so the group was perhaps as short-lived as it was memorable.

And the things Keezer carries today in his memory remain heavy. James Williams and Mulgrew Miller, friends since their days together at Memphis State University, both died young. Williams passed barely 51 in 2004 and Miller, the ensemble’s best-known pianist, died at 57 of a stroke in 2013.

“I think about them every day,” Keezer told me. “They were mentors, they were my guys,” and a clear melancholy fell momentarily over what appears to be the man’s naturally upbeat demeanor.

The ensemble’s senior member Harold Mabern survives, yet he knows of the death of jazz mates perhaps more than Keezer. In 1965, Mabern began playing with Lee Morgan, among the most celebrated of Jazz Messengers. Mabern’s association with Morgan continued on and off until the night in February 1972 that Morgan was shot dead at Slug’s Saloon in lower Manhattan. Mabern was present at the killing, one of the most shocking in jazz history. Morgan was among the most fiery and soulful — and in his last years among the most politically engaged — musicians in jazz. That’s one of the most tragic jazz stories ever, as W.K. Aker’s article details here:

http://narrative.ly/death-of-a-sidewinder/

Morgan was killed by the woman who had saved and loved him, and it’s a long story of drugs, co-dependency and what can happen when a person decides to start carrying a gun.

But for the piano ensemble, it’s notable that Mabern, Miller and Williams – all from Memphis (including Donald Brown) and all African-American – embraced the young white man from Eau Claire. It’s the jazz tradition of democracy and meritocracy – if you can play you can stay, and say your piece. In French, Eau Claire means “clear water” and if the deep, muddy Mississippi on the city’s shore ever provides clarity, it is when it offers up submerged American musical voices in the river for renewed scrutiny and historical appreciation.

Geoff Keezer, now based in San Diego, emerged from the Jazz Messenger hard-bop tradition, and helps advance the music’s ever-extending global currents, including world music and alt-rock. That’s clear on several of his more recent albums, including .

Aurea, Mill Creek Road (with San Diego guitarist Peter Sprague) and The Near Forever. But you can also pay it forward all alone, as in his most recent offering, a solo album, The Heart of the Piano. There you feel a certain loneliness, but also a deep connection to those who’ve come and gone, and left still-untold riches.

____________

Kevin Lynch (Kevernacular) is the author of the forthcoming book, Voices in the River: The Jazz Message to Democracy.

The renovated and revitalized Stoughton Opera House, built at the dawn of the 20th century, now is a Midwest mecca for American roots music.

The renovated and revitalized Stoughton Opera House, built at the dawn of the 20th century, now is a Midwest mecca for American roots music.