I had no anticipation except for perhaps a few pretty pictures when I brought my camera along on my cross-country skiing outing yesterday at Lincoln Park in Milwaukee. And yet, I almost gave up before I started. I drove up and saw that the front of the course and practice green were all literally green in January. The temperature hovered around 40 and, wearing my Christmas present – a long “Weatheredge Plus” Eddie Bauer jacket with hood – I was actually overdressed, as the recent snow was melting very fast. I walked further onto the course and realized enough negotiable snow remained, and embarked on my first skiing outing of the year.

However my body and brain were not ready for the odd patchwork quilt of snow and thatchy grass I was skiing on. A fairly substantial downward incline from the woods on the right side of the golf course’s Par 1 hole, down to the fairway, looked like an enjoyable glide. So I pushed over the precipice and let the skis carry me down the snow and to the edge of a bare grass patch halfway down the hill. Caught by the grass, the skis slowed precipitously, but my body’s speed and momentum did not. I tumbled forward over the skis and down onto the mess of snow and muddy grass. One ski pole flew about eight feet away.

DOH! I might have thought for a moment and anticipated this.

But, no, I learned the hard way, and gradually. I actually fell a couple more times under similar circumstances, but this is partly due to being a little out of practice in cross-country skiing. Normally I do not fall on this nine-hole ski tour, or perhaps just once.

But, no, I learned the hard way, and gradually. I actually fell a couple more times under similar circumstances, but this is partly due to being a little out of practice in cross-country skiing. Normally I do not fall on this nine-hole ski tour, or perhaps just once.

I soon realized this was a literal punch-in-the-gut example of climate change, or global warming. Last year and the year before, when I also took a few pictures here, there had been plenty of snow on mild and amenable winter days. See the two pictures below to compare, first the selfies both taken on the same 6th hole tee vista, and then the views from there of the fifth and six fairways at Lincoln, in 2018 and 2016.

Weather patterns here and around the continent seem in a full regression to a sorrier distance from environmental normalcy and balance. Most all scientists, of course, have plenty of explanation for all this, with consumption of fossil fuels as a primary culprit in this global crisis. Donald Trump’s rejection of the Paris Accord also pushes planet Earth on a long slippery slope in the wrong direction. Virtually all the world’s nations, activists and worthy legislators carry on against climate change, regardless. But this is a tough, tough battle, which environmental scholar/activist Bill McKibbon calls plausibly “World War III.” This post will lead you to his recent essay in The New Republic:

World War III is here and it’s not with North Korea or Russia or any human enemy…

As for my ski outing, I’ll let the pictures do the talking (mostly) from here.

Even the brilliant sun didn’t diminish the snow two years ago on the 6th hole’s playable ground (February 16, 2016, above). Compare to the 2018 selfie scene above.

Likewise, see the snowy 5th green and fairway from the tee of the 6th hole at Lincoln Park, on February 16, 2016

Here’s the same 5th green and fairway from the tee of the 6th hole at Lincoln Park yesterday, January 19, 2018

Here’s the view looking down on Lincoln’s par-3 6th hole yesterday where, two years ago, this scene was covered in snow in February.

As the sun set, I had a long ski hike back (above) from the 6th hole to the club house and parking lot, but the relatively treacherous patches of grass forced me to not build up too much speed on the snow, at least for this out-of-practice cross-country skiier.

But I learned a thing or two while getting plenty of good exercise.

p.s. Monday: Jan 22: The drizzling rain has reduced the snow to a few measly shrinking islands. I was lucky to get that ski outing in. How many more skiiable days will we get this year? Much more importantly, northerly environments need a certain amount of snow yearly to protect flora and fauna from harsh, crippling cold snaps.

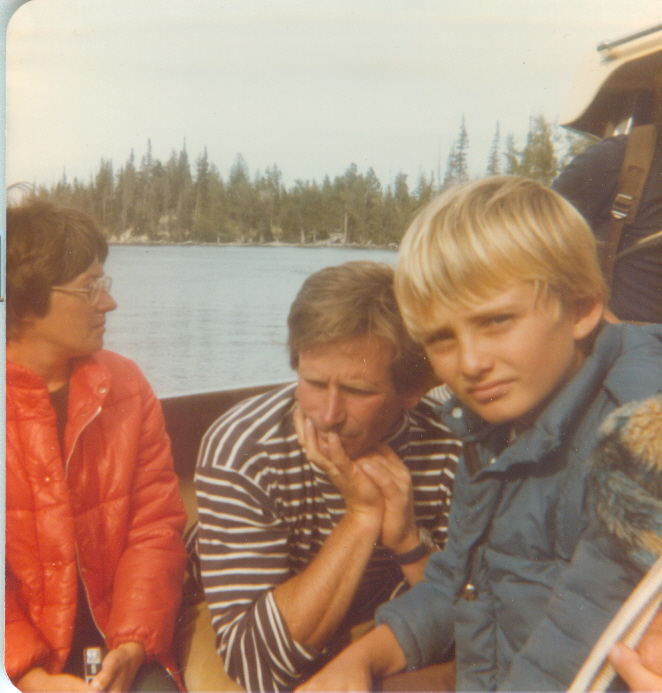

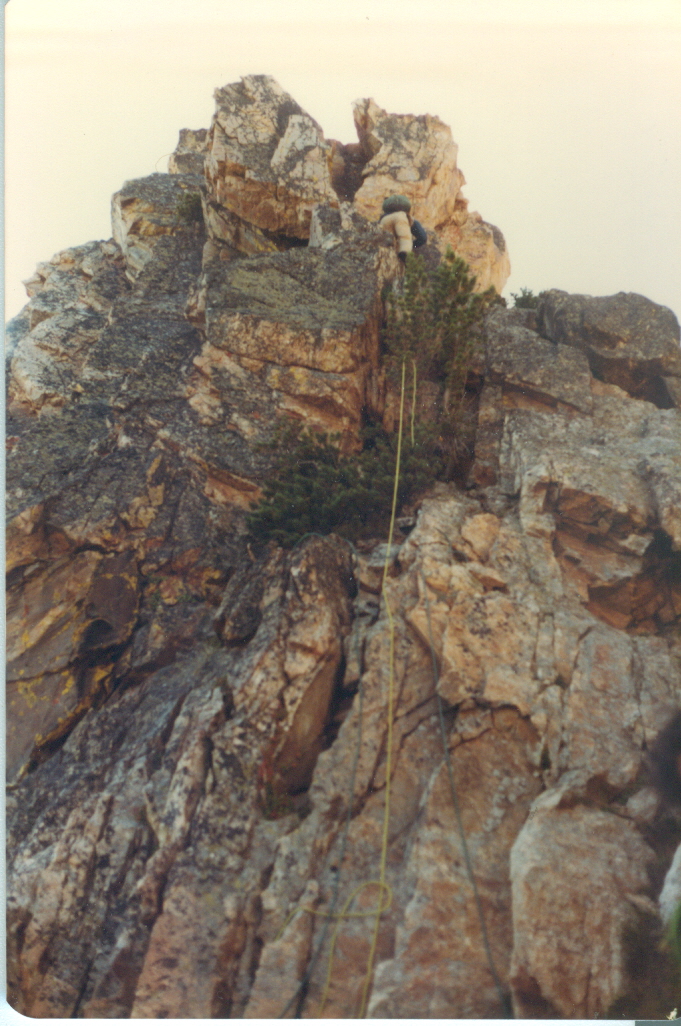

The climb provided some excellent views, on the left is Hanging Canyon from the Arete, and on the right is a view of the ground of Grand Teton National Park, far below.

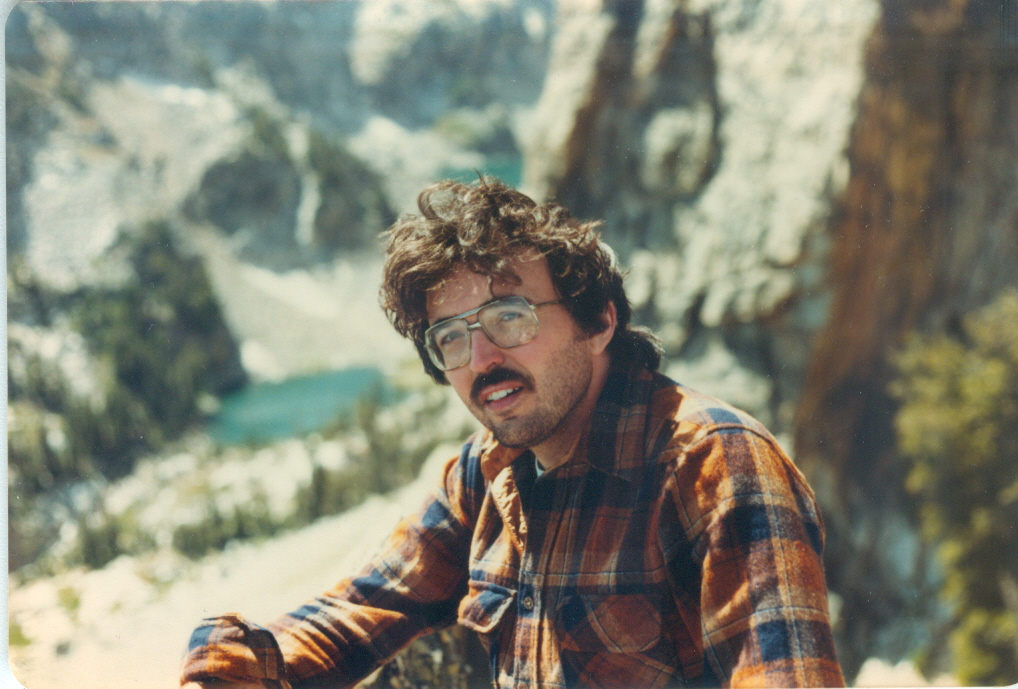

The climb provided some excellent views, on the left is Hanging Canyon from the Arete, and on the right is a view of the ground of Grand Teton National Park, far below. Here’s the Middle Teton in August in the mid-1970s. Note the large face, one of the most imposing in North America, and the distinctive black dike on the face. Photo by Kevin Lynch

Here’s the Middle Teton in August in the mid-1970s. Note the large face, one of the most imposing in North America, and the distinctive black dike on the face. Photo by Kevin Lynch