Kevernacular with Winslow Homer’s “The Berry Pickers” (as it were) in its new home. With Cookie Monster as security guard. Photo by Ann Peterson

Late autumn, it was a surprisingly alluring November day, and I wanted to get to our great lake. I’d felt cooped up by various tasks and distractions on my computer. So I got on my bike and headed from my Riverwest home for Lake Michigan at Atwater Beach in Shorewood.

Little did I know, something like a force of fate led me, in more ways than one – a Winslow Homer-like instinct towards the vast waterfront, to perhaps find inspiration or replenishment, as I had in a recent visit to the Shorewood Nature Preserve on the lakefront, which I documented on a previous blog.

For me, it’s also a Melvillian instinct, which I’m susceptible to, given my deep, rather scholarly interest – some might call it an obsession – with Herman Melville, which has led to me to write a novel-in-progress about the great writer. As Ishmael famously observes in the opening page of Moby-Dick : “Whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul…Then, I count it high time to get to the sea as soon as I can.”

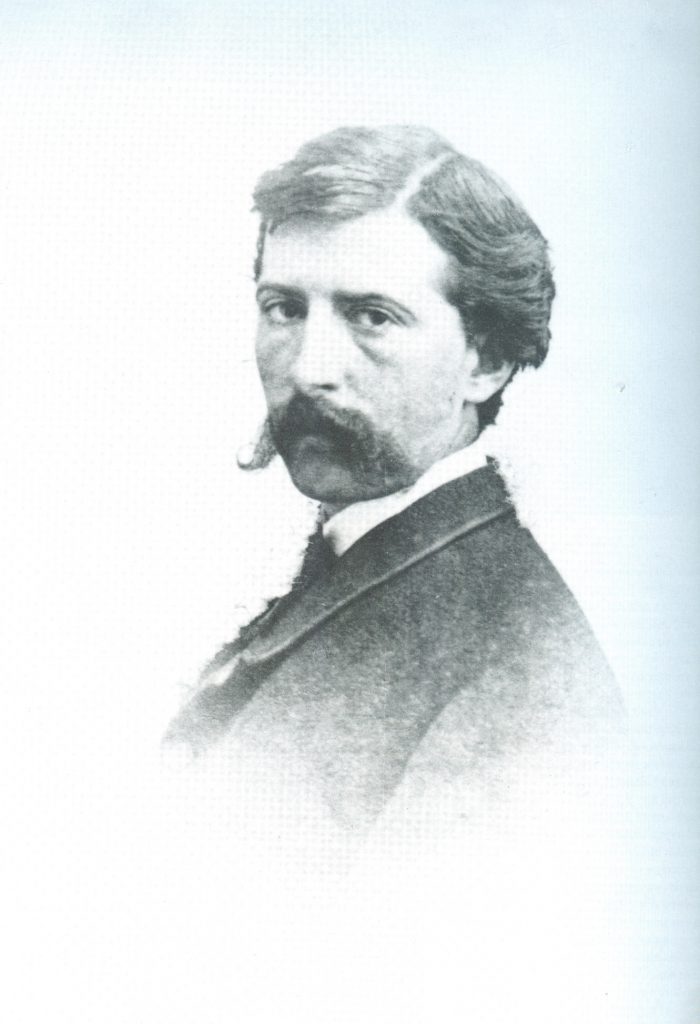

Homer, an East Coast dweller who drew deeply from his close proximity to the ocean, was also inspired by the experience of an English seaport town which helped forge his mature style. The latter point is the premise of a major Winslow Homer exhibit at the Milwaukee Art Museum opening March 1, 2018, for which I will write a preview article for The Shepherd Express newspaper and a more in-depth review on this blog.

Melville and Homer were also sea-loving 19th century contemporaries in forging original American art forms, as part of the so-called “American Renaissance.” Each was arguably the greatest 19th century Americans at their art and craft, and both largely self-taught.

Winslow Homer, 1867, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, from catalogue of exhibit “Winslow Homer,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Gallery of Art and Yale University Press, 1995.

It was surprising, but not really, how many people were down on Atwater Beach that afternoon. Some hardy souls even braved the water trying to catch a few waves to surf on. The lake has a powerful draw for many people. I wondered fancifully how many of these were astrological “water signs” like I am.

After my interlude atop the bluff, I headed back down Capitol Drive and noticed that the mild weather had prompted the second-hand shop Chattel Changers to put out some of its wares on the street. If you’re not in a rush, this place is always a temptation for bargain-hunters of interesting and distinctive used and antique items largely acquired from estate sales and consignment. Plus, I have a personal affinity for this place as years ago it housed The Hayes Gallery, where I had a two-man show of my sculpture, my first gallery showing after my graduation with a BFA at UW-Milwaukee.

The place has an amazing amount of merchandise crammed into its two floors with artwork, furniture, oddities and knick-knacks of every imaginable sort and a number of items of quality craftsmanship. I was actually looking for a gift for someone and, sure enough, I found it, though I can’t reveal that item here.

Chattel Changers. Courtesy Chattel Changers Facebook page.

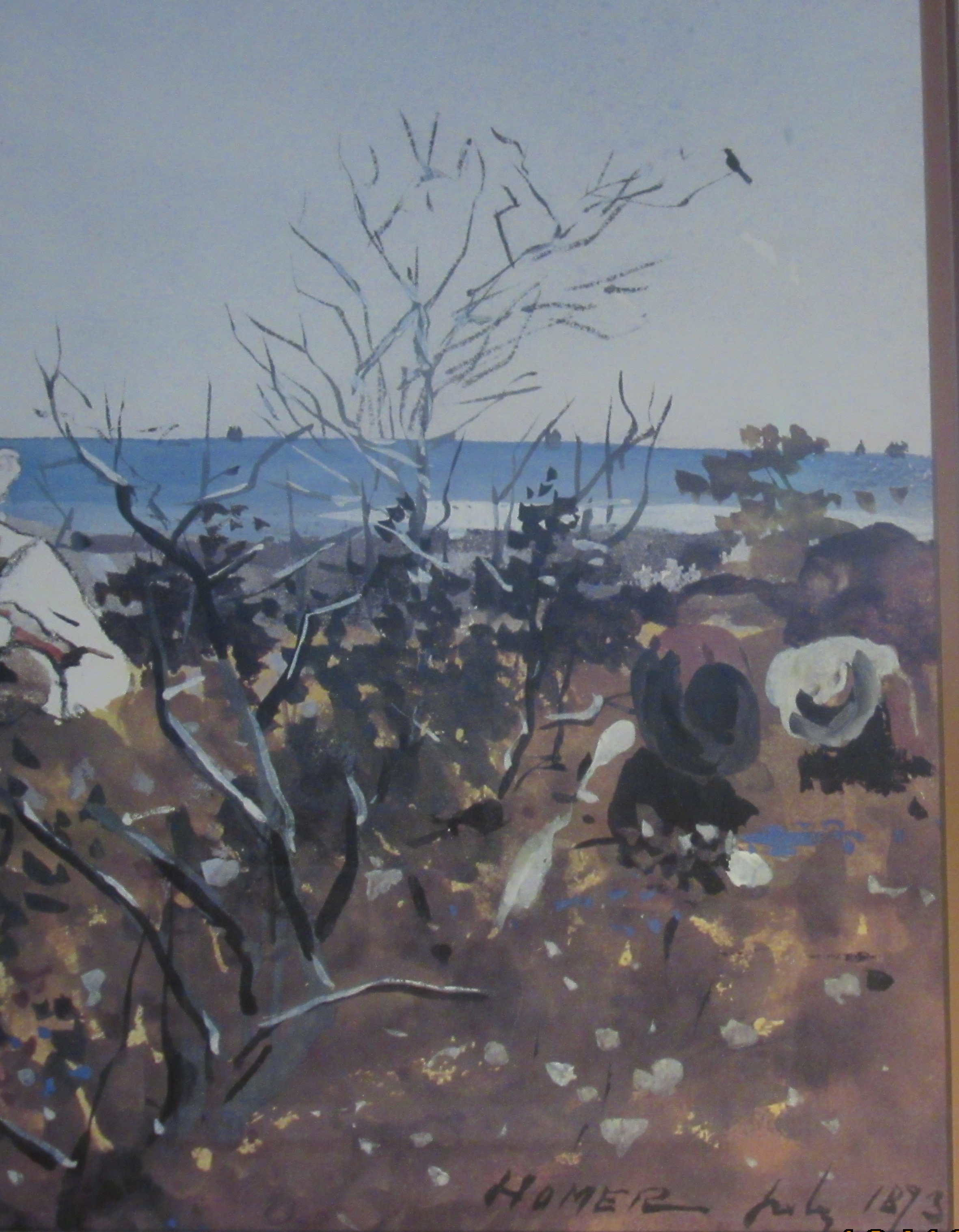

I wandered a bit deeper into the basement when something caught my eye. It looked like a large, framed watercolor painting. It was well-hidden, behind two lamps with fulsome shades. But what struck me immediately was the style of this scene, a depiction of two young women and children hunting for wild berries along a windy coastal spot. “That’s a Winslow Homer,” I said almost aloud to myself.

I had been a fan of Homer’s for a long time and had even once travelled to New York partly to see and write about a major Homer exhibit in 1996 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which included most of his masterpieces, many utterly drenched in ocean experience and drama, such as “Gulf Stream,” “Breezing Up (a Fair Wind), “Undertow,” and “The Life Line.”

My pulse quickened: Even from behind the lampshades, this looked just like a large Homer watercolor, and a scene set on a the Atlantic ocean shore. The label identified the title as “The Berry Pickers” and, yes, Homer’s signature was quite legible in the lower right corner, with the date “July 1873” inscribed. Could this really be a Homer watercolor? It’s well-known that many art treasures hang in the homes of any number of Milwaukee area residences. Could this watercolor have somehow snuck past the discerning eyes of whomever purchases and prices items here? The label said $53.85, but if you know Chattel Changers they have a system of reducing item prices over time with the actual dates of ensuing price reductions listed on the label.

I stood admiring the scene. Two young women stand at the far left, one holding a small pail in her hand. The ocean wind is clearly high from the hat of each woman. The end of an ornamental ribbon flies horizontally from each woman’s hat lid, a deft way to convey the presence of that powerful force of nature. The woman in the foreground leans back against a large boulder, as if to steady herself against the wind. Below the women, several children search knee- or elbow-deep in the underbrush, hoping to pluck the small, precious fruit. On the horizon, the silhouette of a steep hill stands over the edge of the oceanfront horizon. Wispy clouds waft above the berry pickers. The composition, earthy colors and textural qualities add up to something truly beautiful, in Homer’s surprisingly modern manner (more on this later).

I wondered what exactly to do. I peered suspiciously around the room. A few bargain-hunters lurked in the basement room. One woman looked back at me inscrutably. Why exactly did they linger here? I took a deep breath and made a decision. I was traveling by bicycle, so I decided to pay them to hold the gift item, which was too delicate and unwieldy to carry in my backpack, along with some groceries I needed. So I told the cashier I’d be back the next day for it, without mentioning the Homer artwork downstairs.

But I figured it had been here for a while, and I hoped to God that – as obscured as it was by the two large lamps – it would be a safe bet to be there tomorrow.

I slept fitfully that night, and I thought: “Fool! Why didn’t you ask them to hold it for you?” I returned in my car in the morning, shortly after they opened.

I went down the stairs and into the back room. Sure enough, the Homer artwork remained, waiting for me, like a gorgeous but impatient blind date, who didn’t know me from Adam.

With some contortion of effort, I reached past the two bulbous lampshades and managed to pull “The Berry Pickers” down off the wall and take a better look at it under direct lamplight. On the back I saw a large label: “‘The Berry Pickers,’ Winslow Homer. The Colby College Museum of Art.’ ” 1

I turned it back over and saw that the aqueous, gestural quality of the watercolor seemed quite real. I could also see portions of the loosely-rendered outlines of the figures and the landscape that Homer had sketched out in pencil or graphite. Then, I looked closer at the paper itself. I could detect no texture characteristic of watercolor paper, nor had it any signs of aging, for ostensibly being 144-year-old paper. I let out a wistful sigh, and realized I was looking at a reproduction, although a very good one. Nevertheless, this was a sturdily-framed reproduction that, at a glance and even an extended appreciation, looks for all the world like a large and real Winslow Homer watercolor.

I figured, I’ve got to get this for $50, and I’d find a place for it on my already art-filled walls. I got upstairs and asked for the gift item they had held for me. Then I asked what precisely the cost was for the Homer watercolor reproduction. The woman did a little calculating and said, “Twenty dollars.”

Twenty dollars. My disappointment over the possible steal of a lifetime rekindled in realizing I could own this handsome, quite lovely Homer image in my home for a mere twenty bucks. And here, a few blocks from Lake Michigan, this was the sort of find you might expect to luck upon in a similar shop a few blocks from Homer’s beloved stormy Atlantic Ocean.

Though I own plenty of original art, I’m hardly too proud or well-off to frame and hang good reproductions. Among my personal favorites are of Sam Francis’s great 1958 abstract-expressionist painting “The Whiteness of the Whale,” named for a famous chapter in Moby-Dick, as well as a reproduction of Honore Daumier’s marvelous painting of social-commentary art “Third-Class Carriage,” from 1862, which I’d given to my mother long ago as a gift, and received it back when she passed away in 2009.

I loaded up my car with my treasures and headed home.

Part Two: A Close Look at Winslow Homer’s “The Berry Pickers.”

Why Was I so captivated by my newly-purchased reproduction of Homer’s “The Berry Pickers”? One overarching reason is that Homer’s work is akin to the innovative American literary breakthroughs of Melville, Whitman, Thoreau, Dickinson, and Poe, which continue to stimulate and even challenge us today. Homer embraced, interpreted and captured the richness and wildness of a New World that was still only partially tamed. He captured America asserting its power in its relation to the world and understood coming to terms with its relationship to the rough grandeur and beauty of the American landscape and its mighty surrounding oceans. That amounted to a distinctively American style and sensibility, one that had shed the dominant conventions and presuppositions of European culture.

Being largely self-taught, he took from certain timeless values of Western culture while reasserting his own native instincts and talents.

Although the subject matter of the berry pickers is hardly heroic or dramatic, it describes an aspect of our relation to our indigenous natural setting and resources. And for me, Homer found liberation in his creative quest, and anticipated European modernists in his stylistic innovations by several decades.

Take a closer look at “The Berry Pickers.” Homer delights in the opportunity to use watercolor on a large and fairly expensive scale. And he understands implicitly when less is more, and the way you can use negative space as part of your storytelling and composition and visual dynamics.

Notice the two details of the watercolor I have highlighted here. In the first, (above, with his signature at the bottom), you see a rather footloose and fancy smattering and smearing of brushwork and paint in suggesting the summery field blooming with wildflowers and fruit. The bounty, and the berry-picking figures in the lower right corner are represented by suggestive smudges and globs with only roughly-hewn renderings of their sun hats clearly specifying their presence. Branches of the trees counterpoint with their own and nearby leaves, in a loose, dancing fashion as they rise above the horizon. And yet Homer is hardly above inserting a touch of playful humor with the small bird that alights upon one of the branches, perhaps waiting to snatch a juicy morsel that falls free amid the joyous picking.

In the second detail (above), you see that Homer actually leaves unpainted large portions of the shoulders, arms and hats of the young hunters in the foreground, freely rendered such as they are. These two whole lower sections amount to a daring, even radical artistic gambit, for 1873. See the yellow-dressed girl’s hair, also very loosely rendered, as are her garment’s folds and bunches. This all forms a meandering abstract pattern that engages the mind and senses. It is almost as if the figures themselves are at one with the freely-growing wilds of the field.

I think this is the sort of close adherence to formal coherence in a loose, articulate yet expressive manner that even the rigorously formalist abstract-expressionist art critic Clement Greenberg would have approved of.

Similarly, the relation between the standing woman in the foreground and her dress, with her jagged cast shadow set against the hulking boulder, is another striking compositional bon mot. The hat ribbons fluttering in the wind inject an element of natural power and action to this enchanting scene.

And yet, Homer also holds his work loosely together along the classical composition “golden mean” by breaking the composition in two-thirds portions, horizontally and vertically. The shore beneath the waterline delineates the horizontal division and the subtle-but-striking presence of the big, pointed mound in the background suggests the division vertically. In effect, the whole scene hangs on that grid.

Overall, Homer clearly strove here to capture a living, breathing scene of beauty. This is a work of abundant lyricism and life and, for sure, something one can easily live with on one’s living room wall, day after day after day.

And all that for twenty dollars.

____________

- Winslow Homer’s original watercolor of “The Berry Pickers” now resides in The National Gallery in Washington, though at the time my reproduction was framed it evidently was the property of the Colby College Museum of Art, in Waterville, Maine.

Photos by Kevin Lynch, unless otherwise indicated.