Rita Cox and her version of a monkey-wrench code quilt.

____________

If These Quilts Could Talk…African American Quilting Traditions. Quilts by Rita Cox and others. King Drive Commons Gallery and Studio, 2775 N. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, Milwaukee – 414.704.9117.

Remaining exhibit hours with Rita Cox, 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. Saturday, November 10 and 17.

In a wooded region just over the Kentucky border in Ohio, the black woman peered outside and saw no one around. She dragged out a large, richly patterned quilt and hung it out on the clothes line, even though the quilt was not wet. The wind caught the cloth and the fabric danced ponderously alone, waiting for the right set of eyes to arrive to appreciate it.

The day passed and the woman inside the small cabin grew anxious, but held out faith.

Dusk fell and a small group of armed white horsemen trundled up the heavily rutted road. They halted their horses and one man in a uniform dismounted and began patrolling the yard. He poked at the quilt with his rifle. Then he walked up to the door and kicked the door open and found the cabin empty.

The woman had heard the men coming and had gathered her children and hid behind bushes away from their shack, but with a view of the intruders. The sheriff with the rifle, slightly frustrated, walked back out and suddenly fired a shot straight at the hanging quilt. The smallest hiding child wailed and her mother stifled her — that quilt kept the child and two sisters warm at night.

The family huddled in horror, certain the men would find them.

But the sheriff spit on the doorstep and cursed under his breath, then remounted and the group rode away.

Overcome, the mother fell from her crouch down to her knees, in gratitude.

What had happened?

In the same instant her child wailed, a hawk had swooped down with a fierce cry from the opposite direction, distracting the men from the child’s utterance.

Only an hour later, three Africans, fleeing from plantation bondage, came up the very same pathway. The mother, back in her home with her children, saw the three people out front, through the window. One of them noticed the large gunshot hole torn in the quilt.

“Get down, be quiet!” he hissed.

He breathlessly scanned the terrain and heard nothing but the wind whistling through the trees. All of the refugees crept closer to examine the gently waving quilt and, in the early moonlight, spied an image sewn into the cloth pattern — in the shape of a monkey wrench.

This was all they needed to know, for now. It was time for them to return home, pull out a wrench to tighten up the wheels of their wagon and swiftly make all preparations for the hard and perilous flight north, to Canada.

They would hope to reach the next signal — another hanging quilt with another covert symbol, another key to freedom. How much better a hanging quilt than a black man, as Billie Holiday sang, hanging like strange fruit from a poplar tree?

______________

A question remains. Did something like this quilt-signal scene ever take place?

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 decreed that any enslaved Africans who had escaped plantations must be returned to the owners. The woman hanging the coded quilt violated the dubious federal law, risking recrimination as much as the fugitives. The law was stiflingly draconian: Any federal official who did not arrest – or any person aiding – slavery runaways were subject to six months’ imprisonment and a $1,000 fine. Law-enforcement officials were required to arrest any runaway suspect on no more evidence than a claimant’s sworn testimony of ownership. Officers capturing a “fugitive slave” * were entitled to a bonus or promotion for their work. Suspected runaways could not ask for jury trial or testify on their own behalf. 1

Underground Railroad scene painted by Paul Collins. Avisca.com

Underground Railroad scene painted by Paul Collins. Avisca.com

The quilt codes were reportedly used during the period of the Underground Railroad (approximately 1780-1860), the escape-route system for slavery refugees to reach Canada, where the Fugitive Slave Act didn’t apply (Wisconsin was the only U.S. state that did not enforce the act). So brave women began hanging the signal-laden quilts out right on Southern plantations. Yet the quilt code is hidden in the lore of the oral tradition as surely as the quilts themselves. To date, no coded-quilt artifacts from that era remain, says artist Rita Cox, whose quilts are on display.

Nevertheless, quilts were a central part of enslaved and African-American women’s culture, and continue to be, as evidenced by the fascinating traveling exhibit The Quilts of Gee’s Bend at the Milwaukee Art Museum in 2003.

If These Quilts Could Talk…”, Cox’s evocative and provocative King Drive Gallery exhibit of Underground Railroad-inspired “code” quilts, documents what may have been a crucial aspect of communications among Africans attempting to escape bondage during the heyday of slavery and up to the Civil War.

A large crowd gathered for the exhibit opening recently during Gallery Night, a vibrant, multi-cultural event organized by gallery director Marquita Edwards, which included live jazz by the Larry Moore Trio, hot food, and performances by several members of the Hansberry-Sands Theater Company. Edwards sees the event as providing community healing though the arts, “a holistic, preventative approach to living.” She also operates a holistic fitness studio next door.

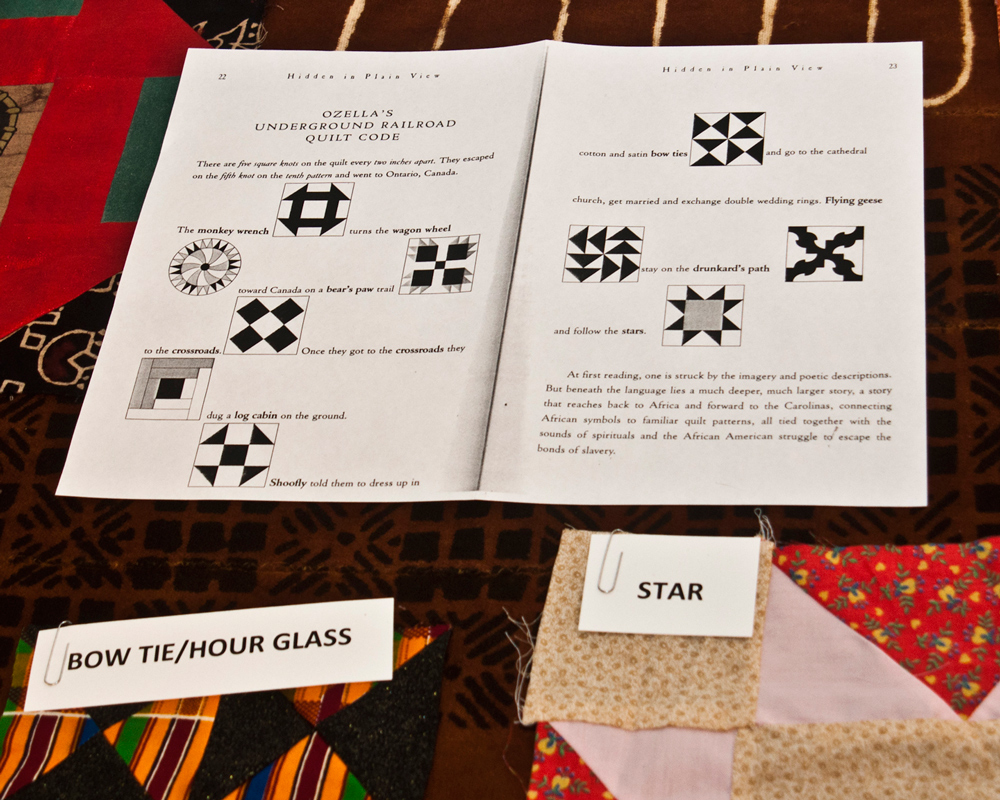

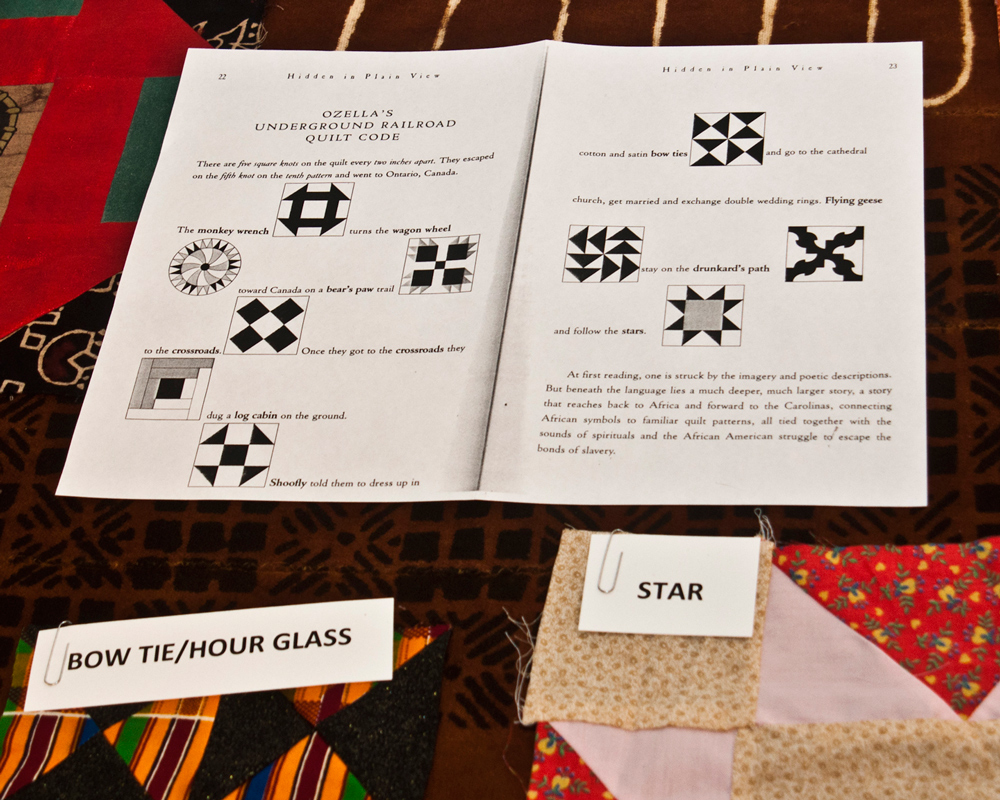

Photos of Rita Cox and pages of “Hidden in Plain View” by Richard Allen

Each of the large quilts by Cox is a down-home, New World symphony of vibrant colors, textures and patterns. By turns rough-hewn and elegant, the sewn cloth swatches nudge, elbow and commingle with each other. Yet Cox’s artful eye and mastery of both machine and hand stitching organizes each whole into visually pleasing rhythmic counterpoint.

On Gallery Night, the quilts’ visual musicality echoed the variations spun by saxophonist Moore, or drummer Kim Zick’s sharp partitions of sound and silence in her “Take Five” solo.

And within each quilt pattern lies a visual symbol that, according to the African-American oral tradition, signaled or instructed escaped black plantation laborers on how to reach freedom.

Although the story of “code quilts” has persisted in the black oral tradition at least since the 1800s, it gained little wider visibility or credence until the 1999 book Hidden In Plain View: A Secret Story Of Quilts And The Underground Railroad, which informed and inspired Cox’s quilts.

Pages from the book “Hidden in Plain View.”

The book was written by art historian and Howard University professor, Raymond Dobard, Jr. and Jacqueline Tobin, a Colorado college instructor. Dobard based her interpretations of the quilt blocks on oral testimony of former attorney and quilt vendor Ozella McDaniel Williams, from her family’s oral lore. Williams recited a poem revealing the code to Tobin over a period of three years, (until the total “code” was revealed). Here’s an example of the covert information Tobin received from Williams:

“The monkey wrench (shifting spanner) turns the wagon wheel toward Canada on a bear’s paw trail to the crossroads.”

“Once they got to the crossroads they dug a log cabin on the ground. (bypass) told them to dress up in cotton and satin bow ties and go to the cathedral church, to get married, and exchange double wedding rings

Flying geese stay on the drunkard’s path and follow the stars.”

Each boldfaced term above was illustrated as a quilt-code symbol. After the monkey wrench signal, an important ensuing symbol was the “bears claw,” which directed fugitives to follow bear tracks to water, to sustain them along the exodus.

An accomplished seamstress from childhood, Cox studied fashion design and business at Mount Mary College and learned quilting at an adult enrichment class offered by Milwaukee Public Schools.

“I gravitated to many of these symbols because I liked them before I even knew they were Underground Railroad symbols,” Cox explains.

Underground Railroad Monument, Battle Creek, Michigan http://www.avisca.com/Html/Avisca_2028.htm

Some historians dispute the coded quilts as mere legend because there is no written record before Dobard and Tobin’s book and — following the code of secrecy — many of the stories remained untold.

Yet the dire circumstances of the enslaved Africans’ situation make the story of the coded quilts a plausible reality of necessity, the mother of invention. Southern chattel slavery’s hardships and cruelty stain America’s soul, and were famously dramatized in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Cox reminds us that slave owners forbade Africans to keep many of their traditions, and functional literacy was outlawed for the enslaved.

But an ancient tradition persisted. “The African griot’s job in life was to memorize and pass on orally information to a whole village,” Cox says. “Because it’s not written down, Europeans don’t give it credence.”

“And some of the quilt symbols came from Africa. Unwittingly the slave holders allowed them make these quilt patterns. This gave you information on what to do and not do, without putting anyone in danger or tipping your hand. And they would not discuss the information among people they did not trust,” Cox added.

“How would they know where to go when they spent all their lives on a plantation? They needed a means of communication, because it was against the law for them to read and write.”

It’s rare that decorative art is so fraught with such dark and heroic history. Like a stroke of genius in an espionage caper, the secret symbols worked while hidden — in plain view. They say art imitates life but, in this case, cunning art helped liberate life.

________

The King Drive Gallery quilt exhibit is sponsored by The Martin Luther King Jr. Economic Development Corporation.

* Cox explains that the term “enslaved Africans” is preferred to “slave” because they did not simply “give up or give in to their oppressors; they resisted by every means possible.”

1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fugitive_Slave_Act_of_1850

.

Like this:

Like Loading...