Homer, Winslow; The Gale; 1883–1893; oil on canvas; 76.8 x 122.7 cm (30 1/4 x 48 5/16 in.); Worcester Art Museum, Museum Purchase, 1916.48

Coming Away: Winslow Homer & England

Milwaukee Art Museum, 700 N. Art Museum Dr. March 1 through May 20, 2018

By Kevin Lynch

Why did Winslow Homer – arguably the greatest 19th-century artist of the American experience – need to brave the Atlantic Ocean’s tempestuous waves and sail to England in 1881? He’d become increasingly famous for the most true-to-life paintings of the Civil War and early Reconstruction. And weren’t the British who we fought for our beloved, hard-earned independence?

Nobody knows for sure why he went. His artwork comprises almost all the documents we have of a private, reclusive man’s life. Some critics see him as a kind of Melvillian Ishmael, instinctively needing “to see the watery part of the world.” Homer was hardly traveling to court The Queen. After time in London, he gravitated to the humblest and hardiest, in a remote coastal fishing village, Cullercoats, near Newcastle.

Perhaps, after American dramas subsided, Homer needed new challenges and subjects and more self-edification of the larger world. The Milwaukee Art Museum’s new Homer exhibition, opening March 1, aims to show that he also found his long perspective, his biggest-picture vision, there among the rolled-up sleeves, flopping fish and dripping nets.

Among the revelations were the fisher women, who formed the backbone of a tough life, turning the men’s labors into sustenance and commerce. So Homer over the two-way voyage, came to profoundly understand the violent beauty of the sea, and the stoic humans braced against crashing waves and other elements.

Homer, “The Fisher Girl,” oil on canvas, 1894

His trip enhanced better understanding of his homeland, its people imbued, unlike the Brits, with “the American dream” and New World bounty. Homer began to strip away the “new Eden” myth of America that he, like most other artists, earlier partook of.

The trip was “transformative,” says Brandon Ruud, MAM curator of American Art, who conceived the exhibit with curator Elizabeth Athens of the Worchester Art Museum, where this extraordinarily promising exhibition will travel from. Ruud quotes a contemporary Boston critic, who praised Homer’s art for “giving the truth, coolly confident that the poetry would be found in that.” Realism bled into atmospherics. Ultimately the sea was Homer’s greatest subject, Ruud says. After returning, he moved to another remote location, Prout’s Neck, a tiny Maine peninsula with which the sea often has its wild ways. 1.

The show is book-ended by two great paintings from the 1881-82 Cullercoats period – MAM’s mythical, almost mystical “Hark! The Lark” (Homer’s personal favorite of his own paintings), and the brine-in-the-face drama “The Gale,” from Worchester’s collection – both depicting women.

Of course, the classic damsel-in-distress trope arises in some images, with this largely self-trained genius’s astonishing flair for drama. The exhibit includes the famous, breathtaking “The Lifeline.” A sailor rescues a near-drowned woman from a sinking ship. The two dangle over the snarling sea, transported along a British-invented pulley contraption called the breeches buoy. This iconic scene also radiates symbolism and strong erotic overtones. Their limbs entwine and a soaked dress hugs the contours of a woman bereft, or in rapture?

Homer, “The Life Line,” oil on canvas, 1884

And yet, far more often, Homer’s British and later work depicts strong women as courageous, in their ways, as men. In “The Gale,” a mother, with a terrified toddler peering from a papoose, braves the angry shore, hoping for some sign of her husband’s ship.

Ruud says Homer also spent time in London museums and libraries before venturing to Cullercoats. Inspired by the epic British painter J.M. W. Turner, Homer become a virtuoso of watercolor, pushing that medium into uncharted waters. Photographs of Greek Parthenon sculpture, scholars surmise, helped him further model heroic and mythical figures.

Homer, “Hark! The Lark.” oil on canvas, 1882

See the museum’s own “Hark! The Lark.” Three women, loaded with goods, stand on a hill, ostensibly listening to the bird’s cry. Yet this scene suggests far more, with closely-observed facial portraits – their eyes, dark and gaunt, stare aloft, but their stout bodies brace for something. They convey wary optimism as they gaze high across a distant horizon. Or is it some precipitous foreshadowing in the clouds, equally plausible in such transfixed faces?

Ruud concurs that these, and other Homer works of the period, amount to no less than a proto-feminism rising from this male American artist, right as the women’s suffrage movement gained power.

Homer, “The Cotton Pickers,” oil on canvas, 1876

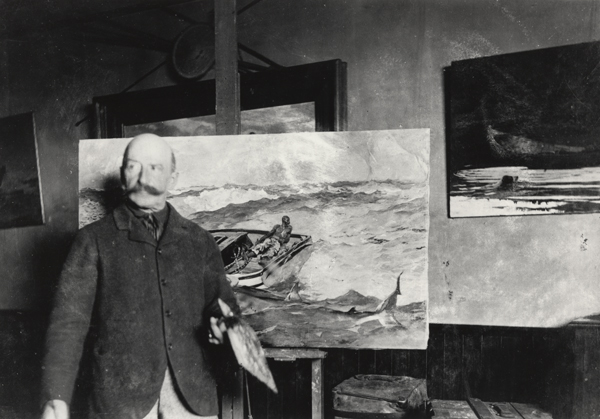

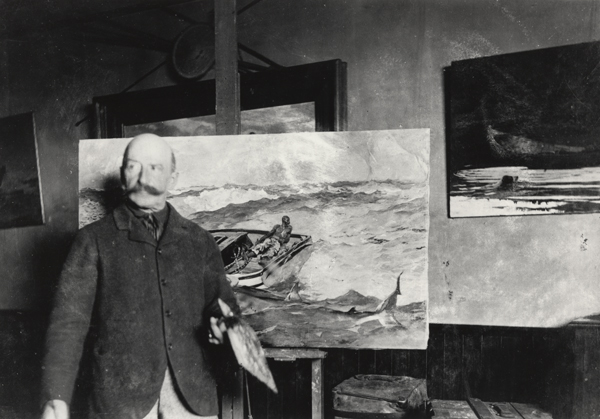

Despite his evident love of America and especially its land and seascapes, Homer proved intensely aware of the nation’s contradictions in its professed ideals, such as sexism and racism. Homer’s “The Cotton Pickers” (above) revealed his social awareness of race issues. Like women, his not infrequent African-American subjects found positions of drama and social dignity. A classic example is his painting “The Gulf Stream” in which a ravenous shark threatens a black man alone out in a small boat that might just capsize. Despite his peril, one doesn’t sense the vigorous man is doomed. A blow-up copy of the photo below of Homer with “The Gulf Stream” canvas is on display at the exhibit (although the actual painting is not).

Photo of Winslow Homer with his painting “The Gulf Stream” is courtesy of Bowdoin College

Partly because of the vast preponderance oil painting in the history of art, it was especially exciting and dramatic to see an artist of Homer’s stature take on watercolor, a medium all too often relegated to Sunday afternoon dabblers. This show demonstrates, especially in a gorgeous work of the finest application, “Fisher Folk in a Dory,” how the medium most akin to water itself stirred Homer’s imagination by turns into tempests and Pacific zephyrs. Such range of moods coexisted within the cold, stormy realms of the North Sea.

Homer became a student of both color theory and watercolor practice as early as 1873 when he began to favor English paints and papers, perhaps another reason for his attraction to the great island. “His experimentation with English techniques, including the subtractive methods of blotting and scraping away color to reveal the white paper underneath, persisted through the ’70s and garnered positive attention from critics,” writes Martha Tedeschi, in her essay for the exhibit catalog. He also learned to apply darker watercolors first, to not obscure lighter ones. His palette thus embraced light’s panoply. A contemporary critic praised these as “pictures in the truest sense.”

What could be more idyllic, even in its hoisting energy, than this windswept sea, seen here with a fisher girl sitting high atop the stern, while the boys prepare the nets and fishing lines, and the breeze hastens a sailboat beyond. The play of pure white light and textured clouds fairly frolics in soft joyousness. Homer went even further by daring to forsake under-drawing and allowing pure, unpredictable water and even a dry brush as principal tools, drawing the scorn of the leading art critic John Ruskin who claimed the artist was “flinging a pot of paint” in the public’s face. 2

Homer, “Fisher Folk in a Dory,” watercolor on paper, 1881

This developed into a dispute which gained international attention and a court battle. But Homer we remained unbent and undeterred. He had discovered something deep and pregnant in this seemingly shallow artistic water. Though he paid great attention to arts critics and his press, he did not always acquiesce to them. His own eye and sensibility remained stronger and true, in his artistic universe. Almost always during this period, hearty humans remain a distinct counterpoint to the vast beyond of the elements he so magically evoked.

Yet finally, in some of Homer’s early 1890s images from the Maine peninsula, the humans recede into solitary figures, amid craggy rocks and swirling tempests. One senses vast loneliness welling inexorably. Like Melville, Homer strives to capture the encompassing indifference of Nature to human existence.

“Because this trip was so transformational his work become more meditative and abstract.” Rudd says. “At the same time, he still does some detailed work, as of old.” Homer’s later work presages the gritty realism of the Ash Can School, and even abstract expressionism, “so with the modern era dawning, Homer is wrestling with his legacy.”

John Sloan, “The Wake of the Ferry No. 2,” oil on canvas, 1907, The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.”

It’s worth considering the renowned “Ash Can” artist John Sloan who, while mainly focusing on the innards of New York’s fast-growing and teeming metropolis, also understood the role the sea played in human fate and fortune. One of Sloan’s more celebrated New York works is “The Wake of the Ferry, No. 2” from 1907, which shares with Homer’s Cullercoats paintings a complex palette, and the weighted, eloquent form of a single female figure, as she gazes out upon steamboats chugging off to sea.

Time and actual artists have proved far more kind to Homer than the likes of John Ruskin, as his legacy has unfurled with increasing resonance, beauty and truth – the qualities most authentic artists pursue. The future will doubtless honor him. For today, we have Coming Away.

________

More information below:

Winslow Homer

American, 1836–1910

Rocky Coast (Maine Coast), c. 1882–1900

Oil on canvas; 14 x 27 in.

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund. Endowed in memory of Leontine Terry Hatch by J.T.S. and D.C.S., 1945.1

All images courtesy of the Milwaukee Art Museum, unless otherwise indicated.

__________

A very relevant show to the Homer exhibit runs concurrently at the MAM, Turning to Turner, in the Godfrey American Art Wing, level II, gallery K230, through April 29. It offers prints by the famous English landscape painter J. M. W. Turner, which reflect what many celebrated as his “truth to nature.” His prints are paired with ones of leading 19th-century American artists, including Homer, who carefully studied Turner’s depictions of the natural world.

Also, the museum will offer several programs and events in conjunction with Coming Away.

Gallery talks,1:30 PM on Tuesdays:

- March 6 and May 15 – with exhibit co-curator Brandon Ruud

- April 7 – a group talk with Ruud and other curators exploring the exhibit from varying perspectives

- May 1 – an exploration of 19th-century fashion depicted in the show’s works with costume scholar Deborah Mancoff.

- Lectures, 6:15 PM Thursdays

- April 5 – “Winslow Homer: International Man of Mystery,” with Sarah Burns, professor emeritus at Indiana University Bloomington.

- May 3 – “Winslow Homer, Ben Shawn, and American Genre Painting” with John Fagg, lecturer in the Department of English literature, and director of the American and Canadian Studies Centre, University of Birmingham.

- April 19 – Perspectives from Milwaukee writer and historian John Gurda, freshwater sciences scholar John Janssen, Milwaukee-based musician Chris Crane and New York-based artist and Milwaukee waterworks project pioneer Mary Miss.

___________

- Brandon Ruud, “Hark! The Lark,” Coming Away: Winslow Homer & England, Yale UP, 2017, 43

- Martha Tedeschi, “Pictures in the Truest Sense: A Reflection on Homer’s English Watercolors,” Coming Away: Winslow Homer & England, 73

A shorter version of this article was published in The Shepherd Express.

Like this:

Like Loading...