Wayne Shorter, who turned 80 in 2013, won the NPR Music Jazz Critics Poll by a large margin.

Wayne Shorter is gone, finally departed this planet and though, as a Buddhist, his sense of the beyond seemed intellectual, who knows how that translates at this point of metaphysical morphing? As a science fiction buff who increasingly incorporated that far-minded sensibility into his own art, he even co-created a 74-page sci-fi graphic novel for his most ambitious work, the three-album Emanon, an extended concerto grosso of sorts, with his jazz quartet and the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra. He grew into a larger, more capacious self over his 89 years, as much as any jazz musician. Here’s where he stepped beyond even this open-minded writer to be honest. Before he died, I’d paused in listening to the demanding epic, and now still have never fully taken in all of Emanon, yet.

Though much great music ensued, I’ll concur with the consensus that the Blue Note album Speak No Evil, recorded at age 31, remains his masterpiece, billowing with shades of mystery and humanity, inspected and illuminated with a forensic sensitivity. I mean, “Dance Cadaverous”? The title tune’s swaggering swing conveys both awareness, and characterization, of evil, haunted by its spread-winged whole notes. That album’s exquisite ballad “Infant Eyes” was a favorite of mine to play on piano before becoming manually disabled. Of course, Shorter’s tenor sax rendering is impossibly tender.

“Speak No Evil” album cover courtesy uDiscover

By then, he was commenting as a kind of “cosmic philosopher,” as he did with “Infant Eyes,” written for his daughter Miyako: “I saw all infancy in her eyes, everyone who’s ever been an infant. An infant being a new start. People reminisce about past stuff, let it take over the present, but with every moment, you’re born.” Such insight feels especially apt now, as perhaps he’s being reborn somewhere, as a star child. Thus, Speak No Evil proved as communicative and heartfelt as is was captivating and challenging.

Other albums from his mid-1960s frieze of noirish Blue Note masterworks include Night Dreamer, Juju, Adam’s Apple, The All-Seeing Eye, Schizophrenia, and The Soothsayer, all necessary listening to gain a sense of the compositional and conceptual talent that sculpted an unfolding progressive profile of modern jazz. Though a bit of an outlier compared to his other Blue Notes, Super Nova is memorable for Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Dindi,” sung by Maria Booker who was, at the time, splitting up with her husband Walter Booker, who accompanied her on guitar. She dissolved into tears amid the recording, which was retained, and the interpretation quivers with poignancy. Part of the lyric:

Like the song of the wind in the trees

That’s how my heart is singing Dindi, happy Dindi

When you’re with me

Yes I do, yes I do

I’d let you go away

If you take me with you

It’s hard to encompass Shorter’s career, and recording-wise that may remain for a major retrospective project or two, surely to come. For now, Columbia’s two-album set Footprints: The Life and Music of Wayne Shorter suffices as an admirable overview of his output, at least to 2004. It complements Michelle Wallace’s same-titled biography, capturing the life of a classification-defying original. And yet his music always had an innate way of redefining lyricism, often contrasting heavy-breathed whole notes with vivid yet eccentric eighth-note phrases. Critic-author Gary Giddins commented on the book, “It makes the case that Wayne Shorter was the representative jazz artist of the past forty-five years, from hard-bop to Miles to fusion to a planet that is too often but inevitably defined as Wayne’s World.”

Album cover to “Footprints: The Life and Music of Wayne Shorter” courtesy Aika Kawasumi

It’s difficult to argue too much with that artistic range and authority, even given the eminence of relative contemporaries as Miles Davis, Coltrane, Mingus, Monk and others.

Mainstream acceptance followed at a respectful distance as Shorter eventually won 12 Grammy awards.

Live performance is the essence of jazz, and I was too young to see the Miles Davis Quintet’s boundary-expanding multi-night 1965 stand at Chicago’s Plugged Nickel nightclub, thankfully preserved on record. Here’s where “free-bop” was sparked and nourished. Shorter’s trademark tune “Footprints” (if any single one can define him) thrives in live performance beyond intimation on the Davis quintet’s Live at Newport 1955-1975 recording on Columbia. Shorter’s tenor solo slows down the band’s rush and casts odd, glancing shadows across the implied footprints — presence and disappearance — even as it rises to an ominous life-force by the solo’s end.

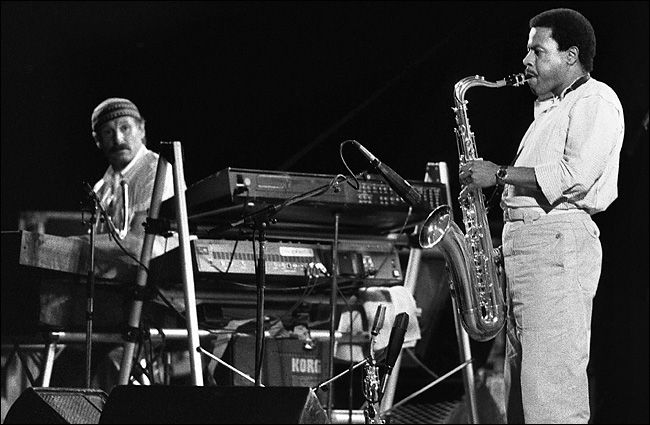

Shorter found the larger pop-rock-funk audience by slipping into the lurking darkness of Miles’s pioneering electric period, notably on Shorter’s “Sanctuary,” on the genre-shattering album Bitches Brew in 1970. This keyed his transition to join Joe Zawinul and uber-bassist Jaco Pastorius in the original Weather Report, which I did see at the Plugged Nickel. Even live, with Zawinul’s electronics and Shorter’s imaginative reinvention of the soprano sax as a soaring, diving falcon-like creature, the band expanded the sonic parameters of jazz while elevating a standard for jazz-fusion which few bands ever equaled. It ranged from the avant-ish debut album to the exotically cinematic “Mysterious Traveller” to Shorter’s “Palladium” a gleaming, exalted, high-flying celebration, the funk-romp jam “Sweetnighter,” and their cloud-hopping hit “Birdland.”

His soprano work with Weather Report was a harbinger, as he’d go on to advance that difficult-to-play-in-tune instrument as far as anyone has, usually to striking and powerful effect.

Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter, the two masterminds and master musicians behind Weather Report, the non-pareil fusion band. courtesy Pinterest

Yet Zawinul was the group’s dominant personality, so inevitably the taciturn, oracular Shorter found his own visionary ways, and soon, with 1974’s Native Dancer, the gloriously gorgeous collaboration with Brazilian singer-songwriter Milton Nascimento. This redefied the jazz-Brazilian connection — songs like “Ponta de Areia” and “Miracle of the Fishes” (an allusion to Jesus?) are uncannily heaven-on-earth in their lush yet humane expansiveness. Sung in Portuguese, both were written by Nascimento and suggest how, though celebrated justly and foremost as a composer, Shorter understood the value of others’ work, including various classical composers, interpreting over the years Villa-Lobos, Sibelius, Mendelssohn, Leroy Anderson, and others.

Another example that early fed his sense of jazz orchestration was playing on Gil Evans’ “Time of the Barracudas.” This restless piece flowed on the dazzling drumming of Elvin Jones in similar effect, if different style, of how Tony Williams fueled the great ‘60s Davis Quintet, and Jack DeJohnette in the first electric Miles band. Jones had played on most of Shorter’s masterful Blue Notes. Of course, Shorter first made his name in the early ‘60s as the precocious music director of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

Such great drummers informed Shorter’s brilliant rhythmic sense in the uniquely and beautifully elliptical way he thought and played. Another career highlight in another composer’s piece was Steely Dan’s deliciously hip “Aja,” perhaps the jazzy pop-rock group’s career musical peak, and there, atop its crest, unfurled a Shorter tenor solo that breathed and exhaled like a celestial god but with his feet on terra firma. The suite’s co-composer Walter Becker commented, “Wayne was very intent on forging a novel approach to the piece. He was influenced by the contour of sections other than the section that he actually played over,” which was basically a single modal-like chord vamp.

This solo and most all of his career reflect his composerly sense of form, even at fast tempos. His improvisational line is ever-shapely yet unpredictable. On a piece like “In Walked Wayne” with trombonist J.J. Johnson, you get a sense of ever replenishing melody and harmony as unfolding. That sculptor’s sense of shape reveal the depth and seeming boundlessness of his genius.

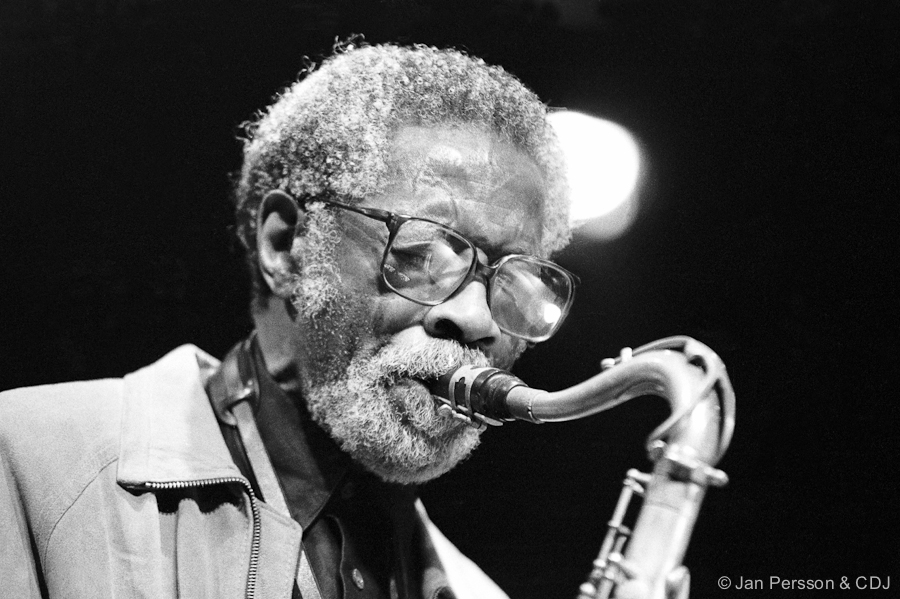

This album cover conveys some of Wayne Shorter’s oracular quality. Courtesy ebay

He played like a fire dragon on the Footprints Live! version of “Masquelero” with his intrepid late-career quartet, pianist Danilo Perez, bassist John Patitucci and dummer Brian Blade. How many musicians his age would still pushing the boundaries of music, flirting with a black hole and a quasar?

His sense of the beyond had come heart-breakingly face-to-face with tragedy when his wife Ana died in the in the 1996 crash of TWA Flight 800. He responded by turning to perhaps his closest musical friend, pianist Herbie Hancock. They produced 1+1, the duo album which elicited “Aung San Suu Kyi,” something focused yet transcendent, with a limpid Shorter soprano solo, a shortcut to wonder and possibility. It was dedicated to and named for the exiled Burmese leader and Nobel Peace Prize winner. “Because we affect lives of those who are here,” Shorter said, “the best way to honor Ana’s life is to become the happiest man alive.” Mercer, writing in the liner notes to the Footprints anthology, comments, “Wayne’s courageous response to his grief was the product and culmination of his Buddhist practice.”

Cover of Shorter’s 3-album with graphic novel set “Emanon.” courtesy WFDD

Of course, later Emanon arose, breaking conceptual ceilings, Wayne Shorter, the star-gazer, at age 85. Wherever he is now travelling, ageless in mystery and in light, we can only hope to imagine and follow.

_____________