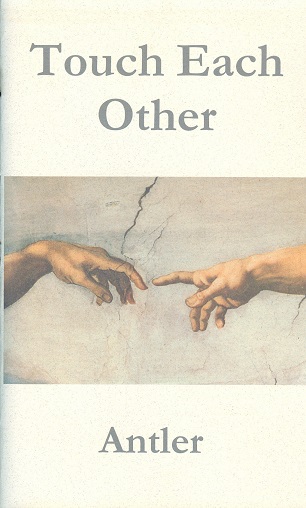

Cover of Antler’s “Touch Each Other.” Courtesy FootHills Publishing.

In honor of Antler’s 80th birthday, I have added to my commentary (in boldface) on his poetry collection “Touch Each Other” from 2013.

I have also added to Antler’s Wikipedia page, including multiple new citations, under the heading of “Antler’s style.”

Touch Each Other (Foothills Publishing) By Antler

Remember Antler’s celebrated and acerbic protest poem “Factory”? He no longer rails, but his middle age still emits an eagle’s cry for vivid dreams and hope.

The former Milwaukee poet laureate’s often-stunning statistical research skirls into billowing “what ifs.” Then, “The Come Cries of the Unborn Come” brilliantly marries birth to last days, and life’s continuum — disarming tired left-right dualisms.

In another: “The existence of money and having to earn it was made up. No longer where floundering when no wonder is why we’re floundering!”

Antler also can be effortlessly pertinent to the moment as in “Threat to our Community,” where spy satellites orbiting the earth take covert photos of “an amoeba in a drop of rain,” of a 13-year-old boy gaping at his sperm through a microscope and of a virtually penniless poet, “while extraterrestrials in a spaceship/ between Uranus and Neptune/train their telescope/on a bum reading the want ads/on a park bench in Golden Gate Park/to see if there are any jobs/ they can apply for/ when they come to San Francisco incognito/ on a reconnaissance mission…”

A generous 40-page chapbook, Touch Each Other‘s title reverberates softly, sensually and spiritually. The latter quality infuses it with spirit for anyone who appreciates great art. Regardless of your opinion of this work you must concede he has spoken to countless people and been celebrated among the greatest of the Beat generation of poet, his prime influence, along with Walt Whitman.

For those, The cover image. a detail of God’s hand reaching to give holy life to Adam, from Michelangelo immortal Sistine Chapel, might strike some as pretentious.

Be prepared for unabashed, hilarious erotica. But please don’t grouse over such outrageous love of life — Whitman’s sacred embrace reborn.

If you think of Milwaukee as basically a blue-collar working-class town that could never abide, say, same-sex marriage, think again.

But first appreciate that as a tired, old classist stereotype, that even as it acknowledges all that Milwaukee has provided the world, working class and engineering masterpieces like the revered Harley Davidson motorcycle, American Motors cars, Allis Chalmers’ pioneering heavy equipment, A.O. Smith, once was the world’s leading producer of car and truck frames. And much more.

Antler, though ostensibly bohemian has done working class labor and addresses that life as honestly and passionately as any poet I know. His early epic masterpiece “Factory,” is based his own experience on the assembly lines at Continental Can Company in Milwaukee.

Unlike most of us, including myself, who also have worked in factories, he happened to have the insight, wit, artistry, eloquence, empathy and passion to transmute the experience into great art.

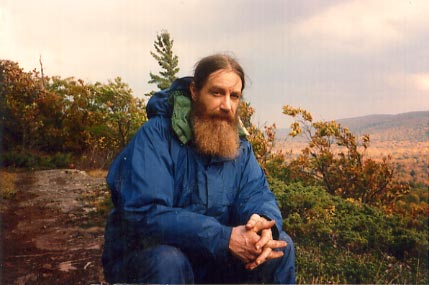

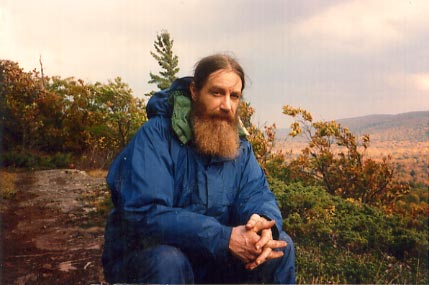

The poet and wilderness explorer Antler is a former Milwaukee poet laureate and winner of the Walt Whitman Award. Courtesy www.antlerpoet.net

Besides direct literary influences, much of Antler does grow like a grand rack of horns, from his vast dedicated experiences in wildernesses. Imagine him standing over you with craggy horns rising upward, nearly piercing the sky. He is a humanist who envisions humanity entwined with nature in the sort of intimate way he envisions himself, humbly but capaciously, full of wonder.

His best big works, and some smaller ones, have the kind of capaciousness that Whitman was celebrated for as an unprecedented American poet.

So, it’s no surprise that Antler won the Walt Whitman Association’s Walt Whitman Award in 1985, for author “whose contribution best reveals the continuing presence of Walt Whitman in American poetry.”

What do I mean by capacious? There are few living poets who write in a straight-shooting vernacular style that can gently grab hold of your mind’s eye and not let go, until he exhales his last beautiful or harsh truth, or until he’s hoisted you onto a high, breath-taking granite vista to see and feel pain and possibility, as if it were just within reach. in other words, he embodies this blog’s subtitle (Vernaculars Speak) as powerfully as any Wisconsin poet,

So yes, he’s the state’s “greatest gay poet,” as Paul Masterson of Shepherd Express has proclaimed. The critic aptly wrote in 2017, “Exploring the emotional arch of male-male love most would find too intimate to express, his gay-themed poems are among his most moving for their raw candor.”

Not to diminish that, but he’s more, in my book, a former Milwaukee poet laureate well worth such honor whose voice reaches to this state’s greatest borders, like all the lakes and riverways that feed the wonder of wilderness that Antler lives and thrives from.

His poem “Feral” helps convey his imaginative vision:

Boy raised by wolves, raised by panthers, boy raised by dolphins, raised by sequoias,/

Boy raised by spirits of plant-eating dinosaurs/

Boy raised by the cave behind the waterfall…”

Wolves, panthers, dolphins, sequoias, spirits, dinosaurs, waterfalls. This sort of beautiful thinking can astonish a reader the more one considers its sense of glorious possibility.

So, you think, if only his “what ifs” in Touch Each Other became “why nots,” and then…

By the way, If you ever have a chance, go to hear Antler read his poetry. He declaims with exuberant verve, a sly wit, and a fine feel for the nuances of irony and tenderness in his verse.

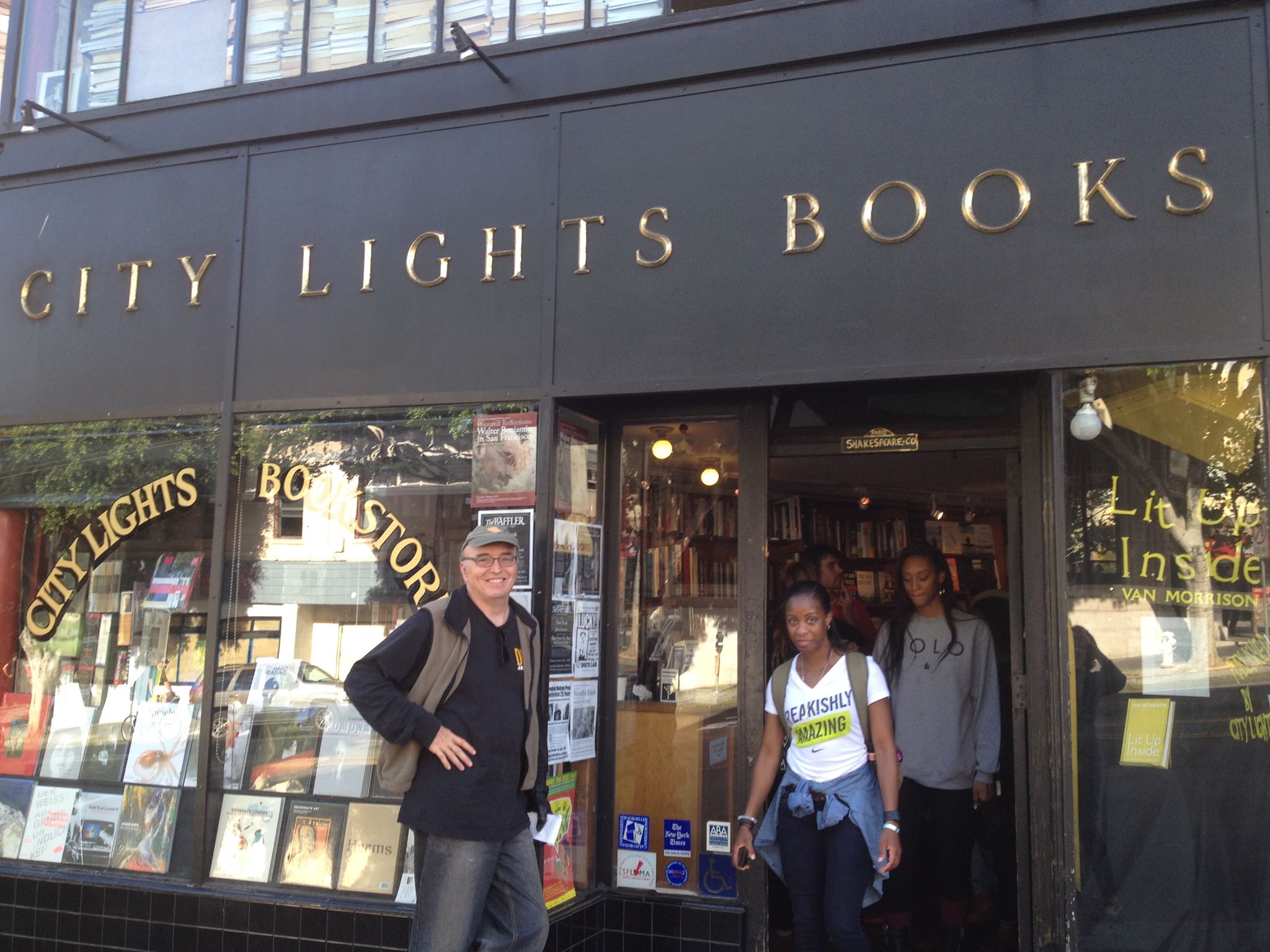

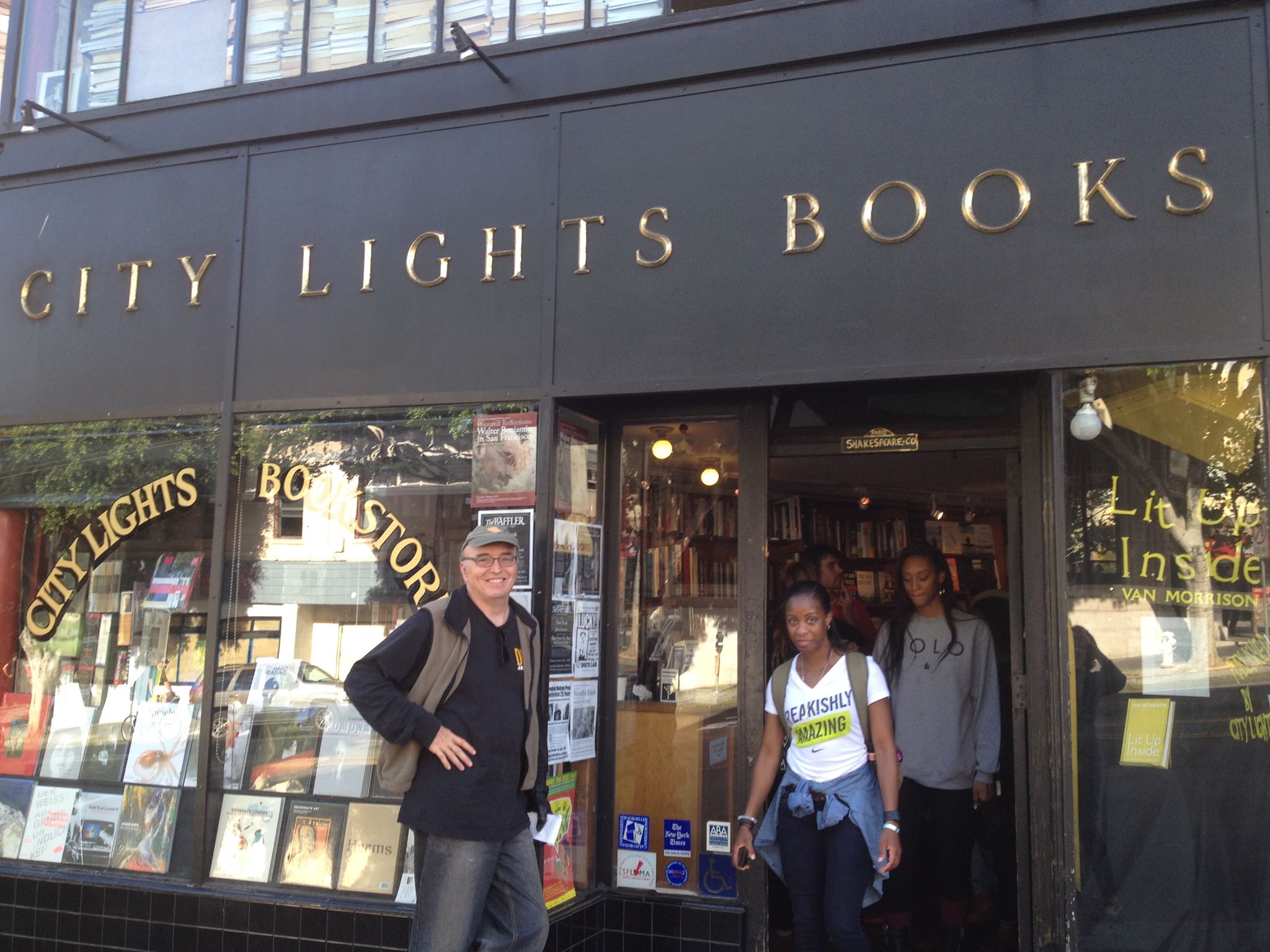

Antler has been acclaimed by such major and kindred poets as Allen Ginsburg, Gary Synder and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who published Factory in the renowned City Lights series.Aside from his Walt Whitman Award, he won the 1987 Witter Bynner Prize awarded annually “to an outstanding younger poet” by the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters in New York City.

Antler was been invited to read at Walt Whitman’s birthplace on Long Island in 2014.

_____________

Touch Each Other is available at Woodland Pattern Book Center in Milwaukee. For more information, visit www.antlerpoet.net.

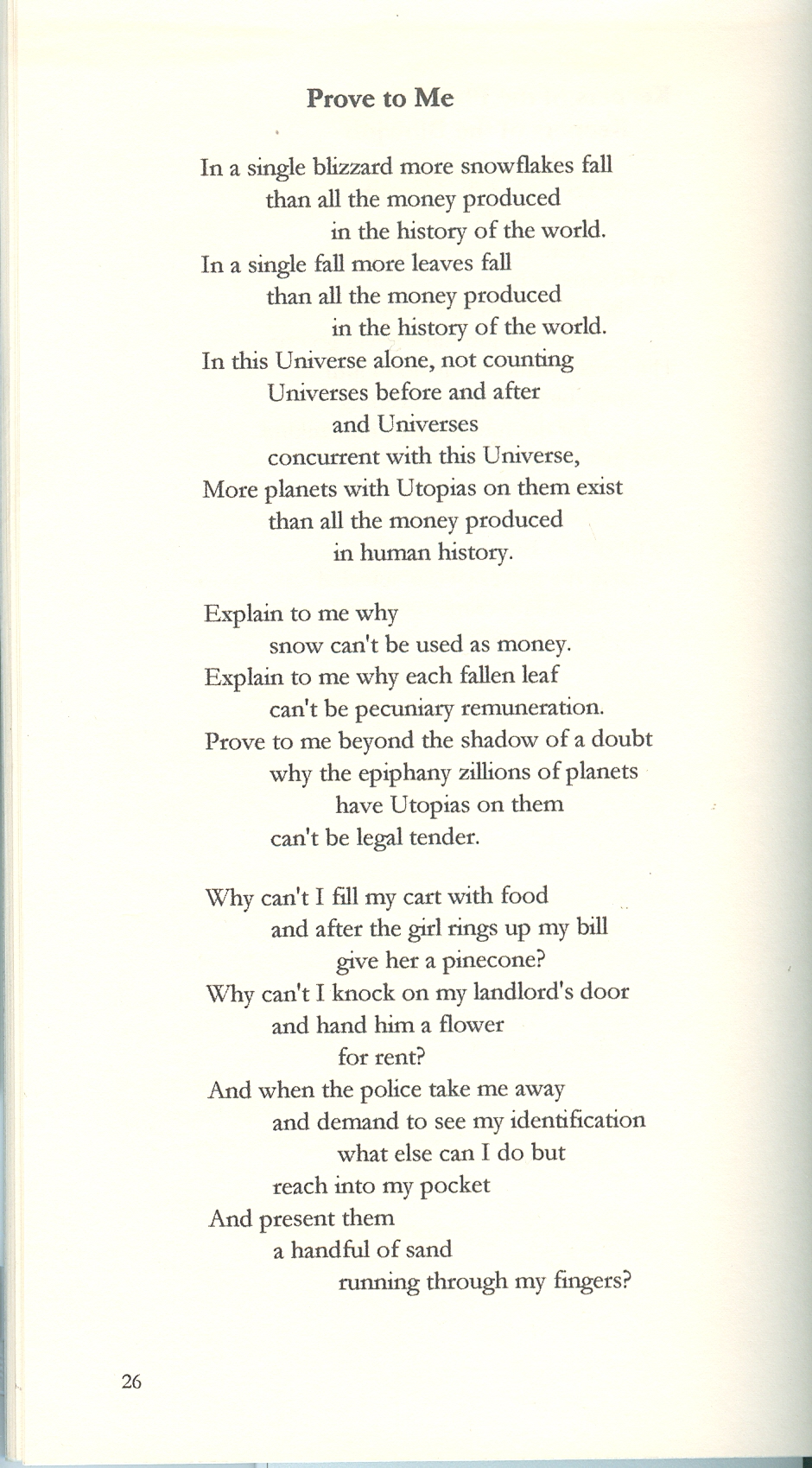

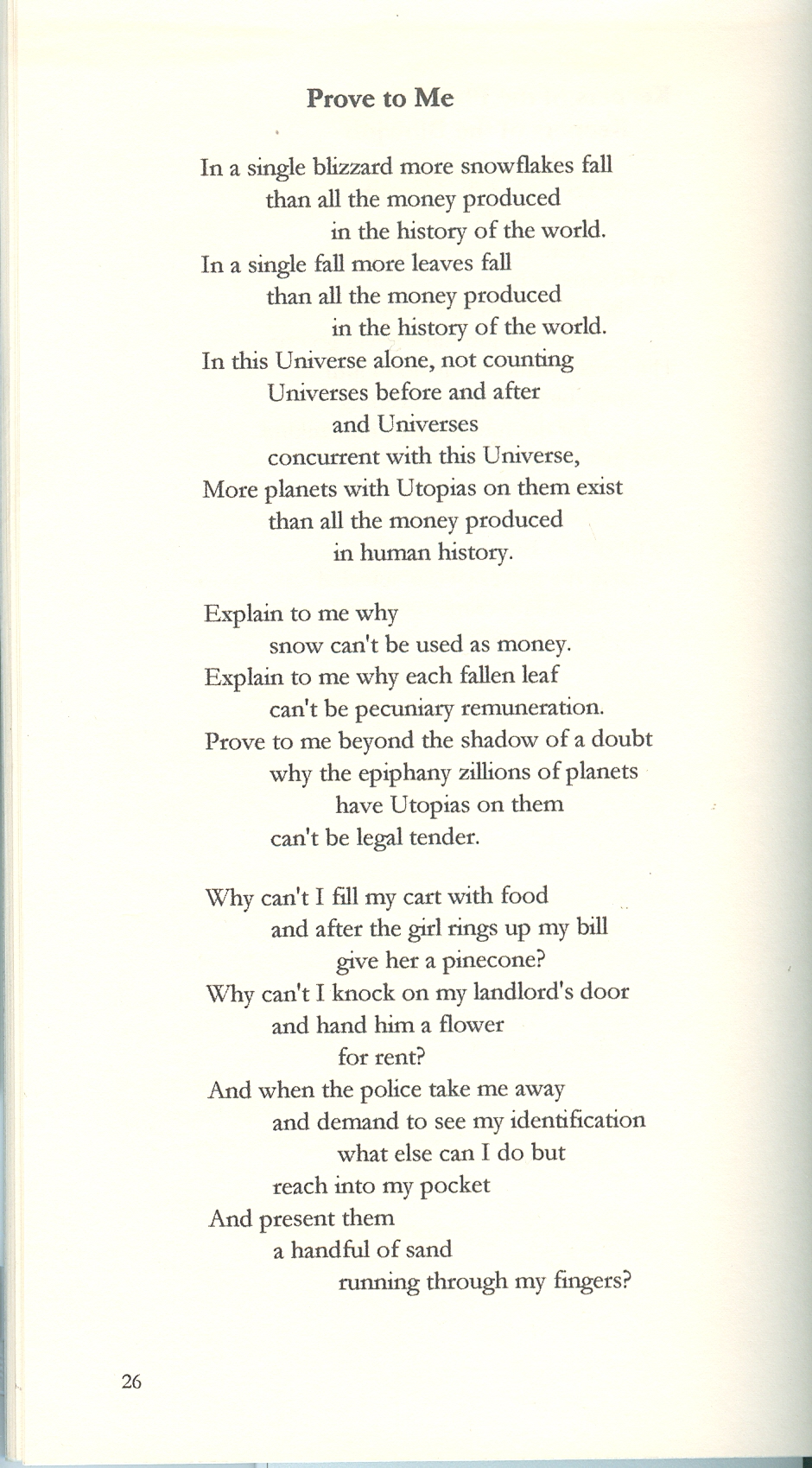

“Prove to Me” from the new chapbook Touch Each Other by Antler

_________

A short version of this post was published in The Shepherd Express, Sept. 4, 2013

Your blogger Kevernacular visits City Light Books in San Francisco, which published Antler’s masterpiece “Factory.” Photo by Ann K. Peterson

Like this:

The trumpeter Lee Morgan was a modern jazz legend, the sort who seemed destined to play in a place like The Milwaukee Jazz Gallery. But he died too soon, in 1972. Six years later, the long-celebrated nightclub and community center opened.

The trumpeter Lee Morgan was a modern jazz legend, the sort who seemed destined to play in a place like The Milwaukee Jazz Gallery. But he died too soon, in 1972. Six years later, the long-celebrated nightclub and community center opened.

I was at the creative wrting festival and i go to wawautosa east i was in one of your seassions and i realy like your poem form the book touch each other i was woundering of you can send me

the poem? It was the last one you read that had us sent into a fit of giggles. it what mean a lot

“Prove to Me” speaks volumes about the sanctity of nature over the war of money. After I read this poem, I immediate bought the book! I have three other books by Antler.

Tom,

You couldn’t have put it more succinctly, about Antler’s newest book. But he’s been speaking powerfully for decades, as you indicate.

Best,

Kevin