Guitarist Bill Frisell (right) and bassist Thomas Morgan.

Having awoken after an evocative Bill Frisell Trio concert, a psychic analogue arose, like a forgotten fairy tale carrying you to yonder realms, enchanted yet vivid fantasia of alluring charm, amid shadows of danger, darker forces, and truths.

Wilhelm (Bill) and Jacob Grimm published their first fairy tales in 1817, hoping to find “some essential truths about the common people.” They even had a scholarly readership in mind, though eventually becoming popular worldwide. (Remember “Snow White,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Hansel and Gretel,” etc.”? Of course.)

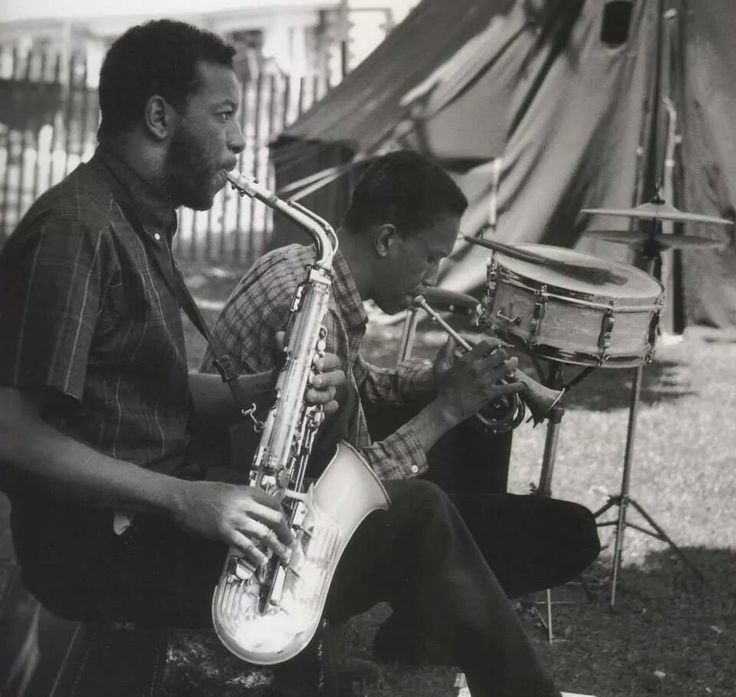

Similarly, Bill’s trio comprises some of the most popular masters of jazz spell-casting. Especially in person at Vivarium Tuesday, the threesome seemed like tellers of tales mysterious and timeless, with quicksilver and wayward imaginations. Not to search out hidden “parables” in this largely instrumental music. But their sonic scenarios signify much of their artful power. Another recent review called the trio “bewitching.” They offer a few standard songs along the way, to provide signposts of familiarity.

A large crowd (and bar crew) sit in rapt attention as The Bill Frisell Trio casts its evocative spell, in the aptly atmospheric and light-blessed concert space Vivarium, on Tuesday evening. All photos by Dan Ojeda, Pabst Theater Group.

But much of the concert was purely improvised. The potent qualities gestate in the moderate-to-slow grooves they mainly work in, as if communing in magic tongues. Often Frisell would pick out a few curious notes that summon a “once upon a time” feel, as bassist Thomas Morgan and drummer Rudy Royston add dialogue murmur, following Frisell’s myriad harmonic overtones and quirky phrase-turns, at times slightly venomous, elsewhere whispering sweetly. It’s like a person who really thinks before he speaks, thus fragmenting his sentences into disarmingly uncertain-sounding grace notes. Yet at times the small silences work like perfectly-timed pauses for dramatic or comic effect.

The Bill Frisell Trio; (L-R) bassist Thomas Morgan, guitarist Frisell and drummer Rudy Royston; plays closely but freely, with and for each other.

This was a high level of artistic playing, just as it contained a childlike level of playing, of odd whimsy, either of which can be subverted at any given moment, creating small wonders and striking suspense. At times Morgan’s bass hung so close in the linear weave to be the guitarist’s breathing counterpoint of charm and tension. These musicians seem to play with and for each other, in the best sense. Royston’s drum set sat sideways, to directly face the bassist, and so master tale-spinner Frisell watched his fellows closely as the music spun a web of simpatico possibility. 1

The audience, in effect, overhears all this sometimes strange and wondrous creativity. One segment involved a slightly ominous descending line that Frisell hooked into a pedal loop, the instant echoing, which sometimes creates a modal raga effect, for him to musically meditate. And yet here it disappeared after two minutes, just as we began to feel it’s subtle powers. Frisell’s then modulates into a fully-formed melody sounding as familiar as one’s favorite recurring fantasy-dream, then collapses into moody cinematics that few guitarists can reach. 2

All this context occurred after a half hour had passed, and Morgan and Royston had taken the only substantial solos. Frisell possesses a kind of leadership modesty like someone far more involved in being a sonic lab scientist with fellow researchers, than making big theoretic pronouncements. Yet later he charged a sequence of rippling Hendrixian flashes and pungent power chords, in a tough but probing passage also recalling Jeff Beck, and all placed precisely in the unfolding way to truth.

Bassist Thomas Morgan

After a lovely, Charlie Haden-esque bass solo from Morgan, and some dissonant Frisell garlands, the guitarist fired up another loop pattern opening into a floating harmonic flow reminiscent of the Grateful Dead, with a crystalline asymmetric phrase ringing like vintage Jerry Garcia. Frisell’s various foot pedals, including “loopers” for the recorded-repeat effect, form a sort of extension of the creative beast in him. One is called a Jam Pedals Tube Dreamer. Perfect. At times, his innate wandering lyricism finds firmer footing and the band kicks up funk and pulsing R&B sorties.

And then the trio unfurled “Who Can I Turn To?” the haltingly beautiful Anthony Newley melody, with a lyric theme wholly befitting this lost-romantic soundscape traveler. Yet the trio really swung mid-song, lifting the mood. These days, Frisell’s hardly a lonesome cowpoke, and he smiles constantly at his bandmates. “You Only Live Twice” offered a different philosophic idea, in a captivating old James Bond theme.

After an encore call brimming vintage Cream City Gemütlichkeit, they came back and played “Shenandoah,” which Frisell has played and recorded so often (and superbly) that you could imagine him tattooed with the title, on his forehead, like a Native American headband. Surely, it’s his favorite theme song.

Like the titular river, the song meandered alluringly, then ended with a couple of Frisell-ish pauses, with grungy fuzz-tone chords, and then a pedal chord — reaching for the Vivarium basement, or the dark mud at the bottom of The Shenandoah.

Frisell marveled, “What a great place! This is the first time I’ve ever been to Milwaukee!”

Count on this beautiful monster returning, as surely as Grimm’s tales echo through the dreams of generations. 3

Bill Frisell speaks to the audience at Vivarium

____________

- This review was originally published in a shorter form in The Shepherd Express: https://shepherdexpress.com/music/concert-reviews/bill-frisell-and-the-artful-power-of-improvisation/

1 This trio also works in another Frisell project called “When you Wish Upon a Star.” which involves the addition of vocalist and violist Petra Haden, daughter of the great late jazz bassist-bandleader and conceptualist Charlie Haden. Frisell has commented on the project: “I’ve been watching TV and movies my entire life. What I’ve seen and heard there is a huge part of, and is embedded so deeply into the fabric of what fires up my musical imagination. The music we play with this group draws from that deep well and hopefully pays tribute to the countless, anonymous, uncredited, unsung, extraordinary musicians who brought that wonderful world to life.”

2 Another Frisell project is The Mesmerists, a collaboration of the guitarist-composer and his other long-standing trio of bassist Tony Scherr and drummer Kenny Wollesen, with innovative film maker Bill Morrison. This project combines the music of Frisell with the films of Morrison “to create musical alchemy…Morrison often combine rare, degraded archival material with contemporary music. The Great Flood, a collaboration with Bill Frisell was honored with a Smithsonian Ingenuity Award for historical scholarship.”

3. Frisell’s sometimes childlike sense of wonder manifested right after he stepped onstage to face the audience. He looked around and said, “Are we gonna keep all these lights on like this?” He then peered up and noticed the eight large skylights extending much of the length of the Vivarium concert space. It’s 7:40 p.m. in Milwaukee, so there’s plenty of friendly sunlight and blue skies still smiling from the heavens.

“Ooops!” he said, chuckling to himself, and his perfectly timed gaffe drew warm laughter from the growing crowd (which reached 276, with some standing-room patrons, a good draw for an act largely identified as “jazz.”)

- Also on the lighter side, I have cropped a close-up (with contrast adjustments) of Frisell’s Fender Stratocaster guitar (below).

- Apologies to photographer Dan Ojeda. But more visible here are playful, amateurish drawings evident on Fisell’s guitar face, which may reveal something about him. It appears to be a male head and gesturing hands at the lower left and a female facing him from the upper right, as if an effort to communicate or connect. We know he’s something of a romantic. Take it from there.

- Link to file image: fRISELL AT mke