The sky hangs shrouded in greys today, and the ground increasingly blanketed with fallen, dying leaves, even as flashes of fading autumn glory continue to cling to trees above.

That all seems very appropriate for Veterans Day today. I hung out my 13-star American flag, signifying America’s founding colonies.

And my soul feels heavy today, but not overcome. I offer this post humbly to honor all veterans, living and dead. But I am personally prompted by two veterans who have passed away, and not in the romantically heroic manner of a battlefield death.

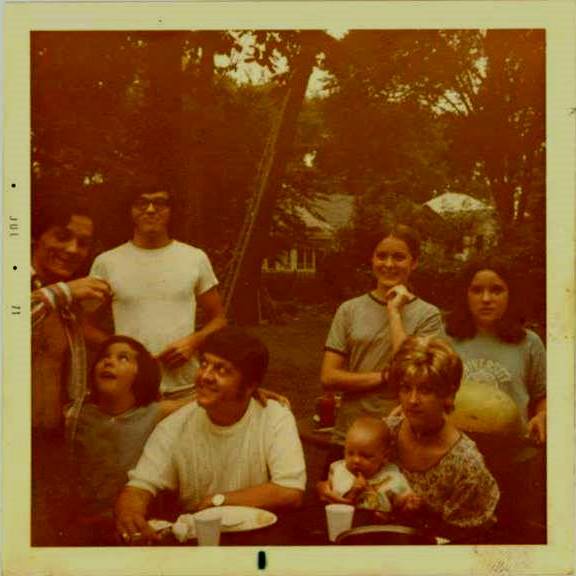

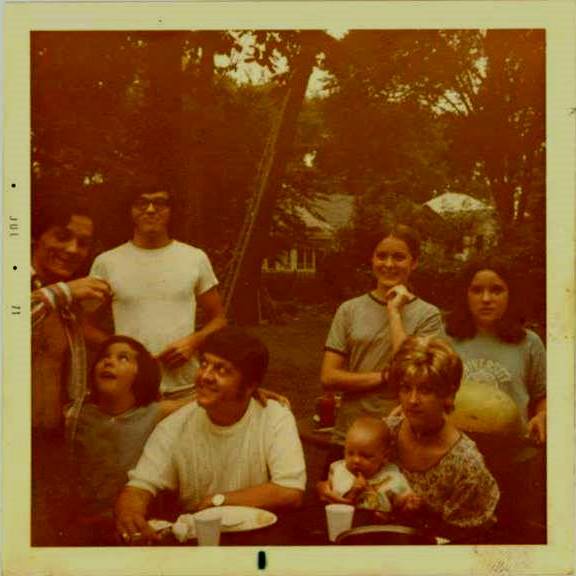

The first was my late cousin John Zeh, who served as a gunner on a helicopter in the Vietnam War. John survived the war, but upon returning back home after his service the Agent Orange poisoning his body began to take its toll, and he died. It was the byproduct of rampant napalm spraying of Vietnam by the U.S. during the war, ultimately an insidious sort of “friendly fire.”

Sadly John Zeh is not listed among those late veterans names etched in the beautifully magnificent and understated Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, an oversight in my opinion. John was a great guy, a good husband and father, and a funny fellow, and is still deeply missed.

*

In 1971, my late cousin John Zeh sits in the middle foreground, after his return from Vietnam War service. He wore a wig due to baldness incurred by chemotherapy for Agent Orange, the Vietnam War-era affliction which ultimately killed him. This happy occasion also includes (from left) John’s brother Bill Zeh, my sister Anne, myself, my sister Betty, John’s wife Karin Zeh and their child Teri, and my sister Sheila.

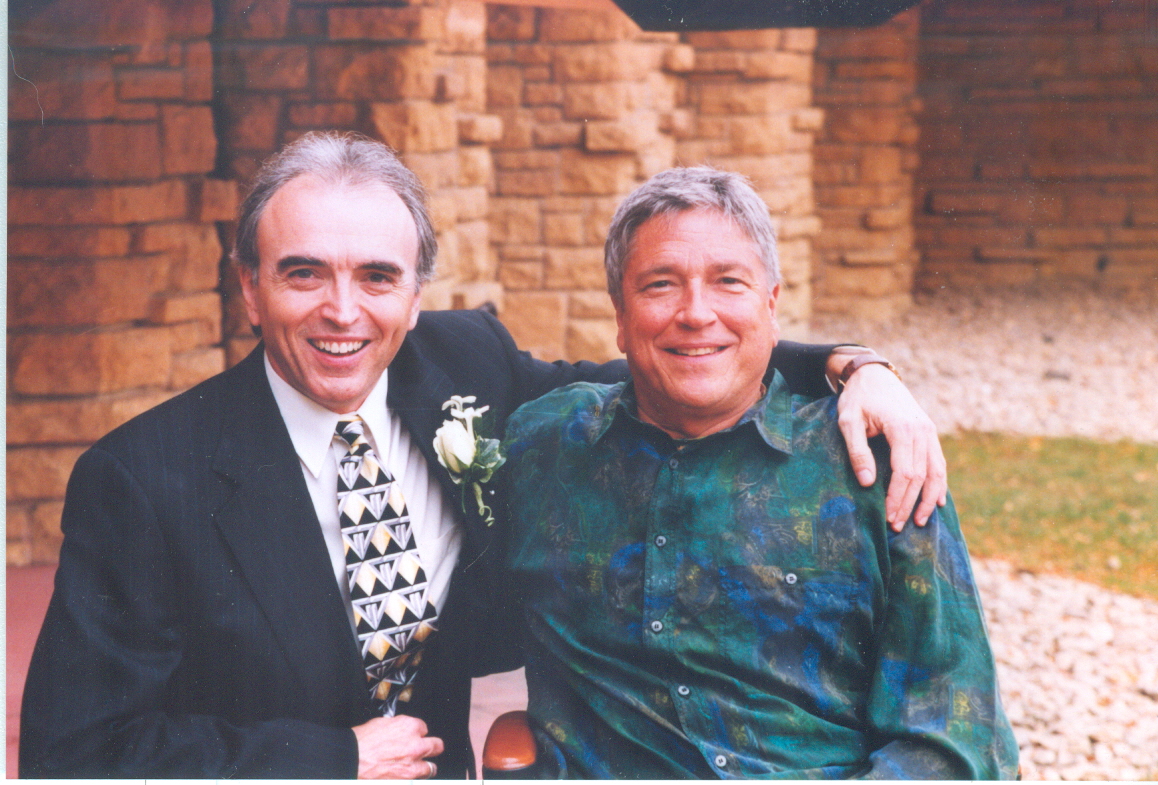

The second departed veteran was a very close friend of mine, Jim Glynn who died in October of 2004 of bladder cancer, which I am convinced arose from his need to use catheters for all the post-war years he lived vibrantly as a paraplegic disabled veteran. Jim is well-known in the Milwaukee music community for his popular, long-time eclectic jazz radio program on WMSE, also as a flutist-percussionist, and a grade-A culture vulture who consistently, despite his disability, directly supported and attended countless arts events in our community.

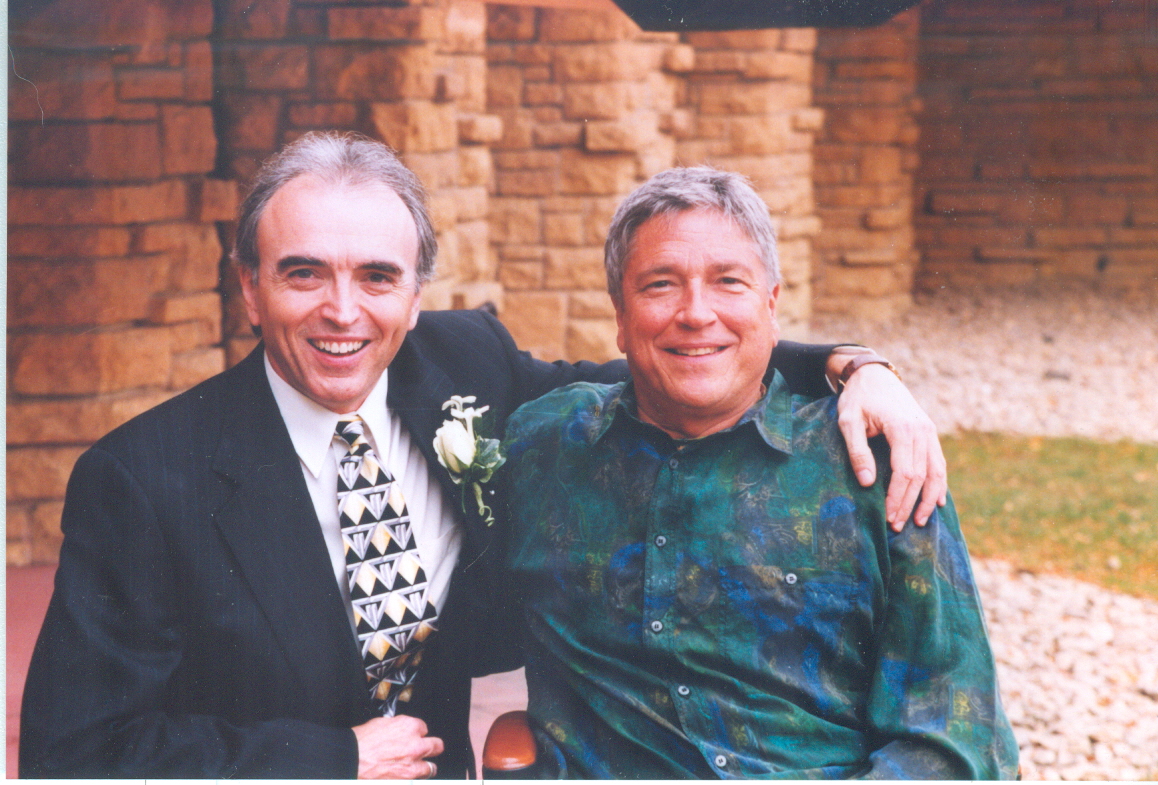

Disabled veteran Jim Glynn, right, served as the best man for my wedding in October 1997..

Jim also served during the Vietnam War although he was stationed in Europe. One day he was riding in a Jeep which lost control. He was thrown from the vehicle and the catastrophic injury to his legs left him paralyzed, unable to walk ever again, without crutches.

I recently had the pleasure to selected some CDs from his magnificent music collection, which he bequeathed to me, but his sister Shannon has kept it stored for some years and we agreed to allow it to be offered among certain friends and disc jockeys. It was a joy to see his collection again. The collection reportedly will be digitally filed and made available online by WMSE. Roaming through the boxes of CDs was a sweet experience that also reached in and pressed on my heart like a great elegy.

I have done radio music programs in the past and I hope to do a music program after I finished my novel about Herman Melville. I look forward to the opportunity to play some of the music from the Jim Glynn collection.

Speaking of Melville, I offer, on this Veterans Day, one of his wonderful poems “Shiloh: A Requiem” from his book of Civil War poems, Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War, from 1866. It’s an alternative viewpoint to the brilliant and overwhelming immersion of Ken Burns’ recent documemtary TV series The Vietnam War. I also offer this because I think the poem resonates to America today, even though Melville wrote it shortly after the Civil War, and with that great conflict as his subject. Yet the poem reaches far beyond its time, because America today is stricken with great internal conflicts, mired in the same subjects the Civil War was fought over — the profound American stain of racism, and the desire to “preserve the Union” as President Lincoln put it.

Today we suffer from deep schisms over race, that lacerate the nation’s soul, and from the way the current presidential administration seems, for so many, like an increasing threat to our sacred American democracy and way of life, as exemplified by our national motto E pluribus unum: From many, one.

Melville’s complex attitudes toward war were far less optimistic and patriotic than Walt Whitman’s better-known Civil War poems, “Drum-Taps” from Leaves of Grass.

In addressing Melville’s point of view, I turn to the great poetry critic-scholar Helen Vendler from “Melville and the Lyric of History,” one of the supplemental essays in the Prometheus Books edition of Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War.

Vendler’s quote here references a couple of other poems in Battle Pieces which I invite you to investigate but her interpretive points apply aptly to Shiloh: A Requiem:

“Melville can never focus on one aspect, is never content to be single-minded: the costs borne by the brave men drowned in the Tecumseh must haunt the close of Melville’s victory narrative, just as the college colonel, in the brilliant poem of that name, cannot forget, as he leads his exhausted but victorious regimen home, the unspeakable truth that came to him in battle.

“And just as “The March into Virginia” began not with epic narrative but with reflection, enclosed not with narrative but with the tragic knowledge gained both by those who perished in those who lived to fight another day, so “The Battle for the Bay” begins in wisdom, continues with narrative, and ends in the tragedy that must qualify every deeply-felt battle song, even one of victory.” 1

Shiloh is not a poem about victory, it commemorates fallen veterans on both sides of the war. This reflects, to me, the most generous and courageous of spirits as a poetic observer, even if it was too challenging and equivocal for much of Melville’s readership then, and it remains, at times, challenging for contemporary readers. But Battle-Pieces is immensely worthwhile and enjoyable, one of the still-underappreciated masterworks of perhaps the greatest of American creative writers.

Shiloh: A Requiem (April, 1862)

Skimming lightly, wheeling still,

The swallows fly low

Over the field in clouded days,

The forest-field of Shiloh—

Over the field where April rain

Solaced the parched ones stretched in pain

Through the pause of night

That followed the Sunday fight

Around the church of Shiloh—

The church so lone, the log-built one,

That echoed to many a parting groan

And natural prayer

Of dying foemen mingled there—

Foemen at morn, but friends at eve—

Fame or country least their care:

(What like a bullet can undeceive!)

But now they lie low,

While over them the swallows skim,

And all is hushed at Shiloh.

Finally, as a Veterans Day postscript, I offer you an opportunity for a bit of activism, specifically this petition for a cause to benefit

severely disabled veterans.Peace,

Kevin Lynch

1. Helen Vendler, “Melville and the Lyric of History,” supplemental essays to Herman Melville’s Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War, Prometheus Books, 2001, 260-261.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Beach rocks at Shorewood Nature Preserve in 2012. Photo courtesy milwaukeeparks.blogspot.com,

Beach rocks at Shorewood Nature Preserve in 2012. Photo courtesy milwaukeeparks.blogspot.com,