“Hot Shot Eastbound,” Iaeger, West Virginia, 1956. All photos © W. Conway Link

“Hot Shot Eastbound,” Iaeger, West Virginia, 1956. All photos © W. Conway Link

Trains That Passed in the Night: The Railroad Photography of O. Winston Link, running through April 27 at the Grohmann Museum, 1000 N. Broadway, The Milwaukee School of Engineering.

Thomas Garver understands O. Winston Link as a kind of genius who “seduced” viewers with the romance of billowing smoke, thundering pistons, and clattering train tracks. The analogy is apt given Link’s background as a commercial photographer, says the curator of the new exhibit, Trains That Passed in the Night: The Railroad Photography of O. Winston Link, which runs through April 27 at the Grohmann Museum, which collects and exhibits “industrial art.”

The museum’s holdings are built around its Man at Work collection of depictions of human labor and industry, in primarily paintings, mosaics, stained glass and large-scale bronze figure sculptures, some of which adorn the museum’s roof like heroic, larger-than-life gargoyles or, if you prefer, cathedral saints. Museum director James Keiselberg welcomes the Link photography as a complement to the museum’s more traditional media.

Link dealt with a historic American subject in new technological means, for the 1950s. He also instinctively plumbed the dark side of the American experience by taking the radical step of shooting most of his train photos at night. These 36 black-and-white prints — documenting the final days of the steam-powered railroad on the Norfolk & Western Railway — evoke film noir. He used large, cumbersome tripod cameras with flashbulbs, and developed his exquisitely detailed images as gelatin silver prints in dark rooms, using beds of liquid developing solution for the exposed print, a “stop bath,” a fixer bath, etc. and mechanical enlargers. In an era of instant digital photography with “smart phones,” all these arcane techniques seem to risk extinction, like the steam locomotive, Garver notes.

Link also recorded locomotive sound effects and filmed this passing railroad environment — part of a documentary film for British television. Garver describes Link’s actual footage as “very atmospheric and romantic.”

So Link’s advertising-style “seduction,” brings the viewer “into the scene which includes the trains, but only as part of the total ensemble.”

Or think of a director’s seduction, in a classic American noir film like Double Indemnity. Here, the murderous threat seems submerged — but not a sense of something dying. What’s passing is the locomotive Iron Horse, and the way of life it helped build across America.

Link’s “ensemble” involved locals as closely directed players, in elaborate setups and lighting, and exquisite timing. His famous 1956 photo “Hot Shot Eastbound,” (top) blends mediums of transport and entertainment, life and death, romance and tragedy — muffled by the train powering by, as an airplane screams across a movie-screen sky. A young couple in a convertible enjoys a drive-in movie as a train hurtles past into darkness.

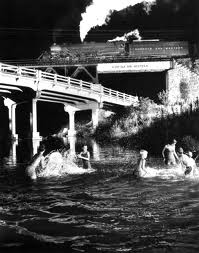

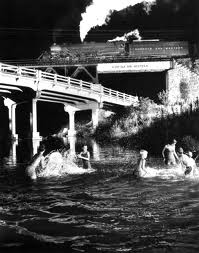

Link seductively downplays tragedy, complicit with the enjoyment amid such “passages.” In “Hawksbill Creek Swimming Home” (above) river bathers frolic with a rather American disregard of fatefulness. Link creates a zig-zag interplay of angles — the current’s ominously black flow, the starkly backlit hill, the skeletal causeway and — in that instant — the train above, like a hell-bound or heaven-sent messenger, depending on your viewpoint.

Included are some daylight train photographs, with their own visual poetry. Link’s magic invariably seems to emanate from the smokestack’s cloud dance. And in one of the daylight photos he manages to capture the passage of an even older means of transportation. What is most striking about “Maud Bows to the Virginia Creeper” (1956, below) is the horse-drawn carriage waiting in the foreground, beside a small train station in Green Cove, Virginia.

Because the rail traversed 55 mountainous and treacherous miles from southwestern Virginia into western North Carolina, the train only ran during daylight hours. However, the head of the elegantly powerful white Maud is bowed, as if she is acquiescing to the propulsive black power of the Iron Horse, surging into the same foreground. The animal instinctively conveys a delicate poignance in the historical moment, intensified by the depth of field, which the train is quickly consuming.

Link was an American original, striving to capture something that was disappearing from the vast panorama that formed the indigenous identity of America. In this sense, he is a kindred spirit to Edward Curtis, who also went to extraordinary lengths, to photographically document the American Indian and the passing of his way of life in his native habitat — during the transformative and often tragic advent of the white man. The Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend recently closed an exhibit of Curtis’ work (which this blog covered extensively, starting with this review at:https://kevernacular.com/?p=2133).

As Curtis did commercial portraiture to survive, Link did advertising photography for The Saturday Evening Post and various technical publications, but trains were his passion, as a subject.

“This was created as a work of passion and belief; that he set out to help in the preservation of a vanishing technology, in the manner he understood best, which was photography,” Garver says.

Link helps us to understand that with fresh eyes, to peer into the captured night, into the steam railroad’s fast-changing times and implicitly into ours.

The Grohmann Museum hours are 9 AM to 5 PM Monday- Friday, Noon-6 PM Saturday, 1-4 PM Sunday. Parking is available east of the Museum at the corner of Milwaukee and State streets. 414-277-2300 Website: www.msoe.edu/museum

A shorter version of this review was published in The Shepherd Express.

_______________________________

Like this:

Like Loading...

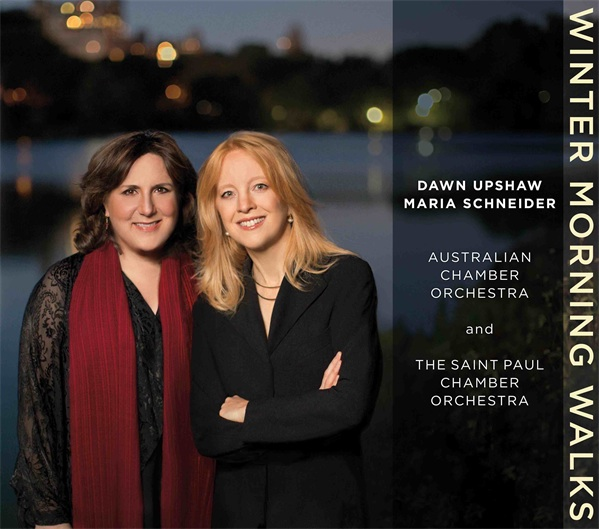

Maria Schneider won 3 Grammy awards in 2014: best classical composition, arrangements and song. Did she deserve all three, in her first recorded outing in the purely classical category?

Maria Schneider won 3 Grammy awards in 2014: best classical composition, arrangements and song. Did she deserve all three, in her first recorded outing in the purely classical category?

“Hot Shot Eastbound,” Iaeger, West Virginia, 1956. All photos © W. Conway Link

“Hot Shot Eastbound,” Iaeger, West Virginia, 1956. All photos © W. Conway Link

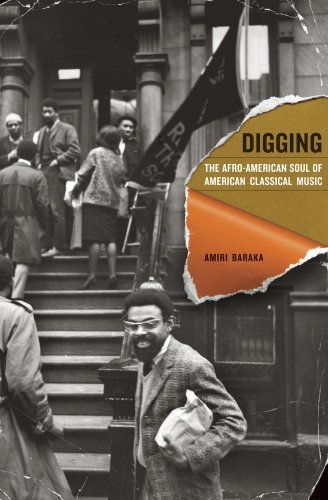

Pioneering black music critic, playwright, essayist, and former Poet Laureate of New Jersey Amiri Baraka died at 79 on Jan. 9 in a Newark hospital. I thank jazz critic, author and educator Howard Mandel for posting a tribute to Baraka on his Facebook page, which prompted this blog post.

Pioneering black music critic, playwright, essayist, and former Poet Laureate of New Jersey Amiri Baraka died at 79 on Jan. 9 in a Newark hospital. I thank jazz critic, author and educator Howard Mandel for posting a tribute to Baraka on his Facebook page, which prompted this blog post. “On the one hand, if we use Afro-American improvised music (American classical music) in the classroom, we would see big changes. Likewise if we began to use all the arts to teach, because there is no depth to education without art. But the constant presence of the music in the classroom hallway cafeteria etc.. would help toward providing that”true self-consciousness” Du Bois spoke of as opposed to the double consciousness these schools try to mash on our children now where they are forced to look at the world through the eyes of people that hate them (even if they are white working-class children).” 1

“On the one hand, if we use Afro-American improvised music (American classical music) in the classroom, we would see big changes. Likewise if we began to use all the arts to teach, because there is no depth to education without art. But the constant presence of the music in the classroom hallway cafeteria etc.. would help toward providing that”true self-consciousness” Du Bois spoke of as opposed to the double consciousness these schools try to mash on our children now where they are forced to look at the world through the eyes of people that hate them (even if they are white working-class children).” 1 “Mr. Baraka’s forthright use of black vernacular, slang and profanity in an improvisatory style became an influence on later writers, hip-hop musicians and playwrights, noted In Matt Schude in an obit for The Washington Post, a publication hardly expected to embrace his legacy. “Arnold Rampersad, the biographer and literary critic, once wrote that Mr. Baraka’s bold writings, coupled with his vibrant social activism, made him one of the most historically significant figures in African American life, alongside Frederick Douglass, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison.

“Mr. Baraka’s forthright use of black vernacular, slang and profanity in an improvisatory style became an influence on later writers, hip-hop musicians and playwrights, noted In Matt Schude in an obit for The Washington Post, a publication hardly expected to embrace his legacy. “Arnold Rampersad, the biographer and literary critic, once wrote that Mr. Baraka’s bold writings, coupled with his vibrant social activism, made him one of the most historically significant figures in African American life, alongside Frederick Douglass, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison.