San Francisco from Telegraph Hill. Photo by Ann Peterson

San Francisco from Telegraph Hill. Photo by Ann Peterson

All classes see each other constantly because they are very close. They communicate and mix with each other every day, they imitate and envy each other; that suggests a host of ideas, notions, and desires to people that they would not have had if ranks had been fixed and society immobile. — Alexis de Tocqueville on “democratic, enlightened, and free centuries.” 1

A Westerly Cultural Travel Journal, Part 2

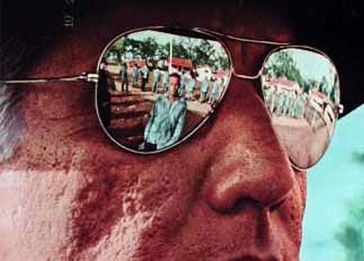

The state borderline into California brought us to a real-live obstacle — a checkpoint at the border manned with uniformed inspectors. We stopped and I rolled down the window and a man peered at us, his broad brimmed hat, sunglasses and a green uniform resembling “The Man with No Eyes” in Cool Hand Luke. He was inspecting for undesirable contraband.  “The Man with No Eyes” from “Cool Hand Luke.” Courtesy democraticunderground.com

“The Man with No Eyes” from “Cool Hand Luke.” Courtesy democraticunderground.com

“Do you have any animals or plants or fruit in the car with you?”

I didn’t expect the question, so I turned to Ann warily and gulped. I looked back to the officer and said earnestly, “Well, um, we have some raisins in our trail mix.” A pregnant pause as he inspected the car. I held my breath.

He (seemed to) look at me again, and said, “That’s fine. You can proceed.”

When we slowly drove on, Ann fell into uncontrollable giggles over my guilty expression and my answer to the officer. I may be sophisticated about some things but I guess, like cherry tree-chopping George Washington, I cannot tell a lie (though I may have hedged on the truth occasionally).

High in the Sierra Nevada mountains the sun disappeared quickly so we tried to stop for dinner before pressing for the coast. We saw a sign for a place called “Rustic Kitchen” which sounded inviting, so we pulled off. We drove down a heavily wooded road not far from the highway, as dusk engulfed us in gray-black murkiness.

There it was. But as we drove up we noticed a handful of men in the restaurant. In the next instant, as several of them peered out at our car — all the lights went out inside.

“This isn’t a good sign,” said Ann, ever wary. Moments later, one of the men came out with a crooked smile on his face. “Just wondering if the restaurant’s open,” I said. “We came a long ways.”

“Nope. Funny thing but we just had a fire here recently so we’re closed temporarily. Sorry about that.”

He pointed yonder and told us of a couple of dining options down the highway. We drove away and agreed that it looked suspicious: the lights going out as we drove up, the man coming out to make sure we would not enter and see the goings-on inside.

The alpine evergreens stood, silhouetted against the last glimmer of sky light, like giant shrouds. Ann felt spooked and I flashed on David Lynch’s psychological thriller TV series Twin Peaks, set in rural Washington State. Did I hear slithering bass clarinet music following us? The restaurant scene may have been innocent, some guys playing a dollar-a-hand poker game. But what would ace detective Adrian Monk think? After all, he solves crime mysteries in San Francisco, just where we’re headed…”It’s a jungle out there.”

We actually reached “The City” in deep night, at the end of our third day of driving. We crossed the majestic, glimmering Oakland Bay Bridge and found our hotel without too much difficulty. Well, Ann may beg to differ — she was driving and I tried to navigate us through busy one-way and ultra-steep streets. You see, the third game of the World Series — Giants versus Royals — was happening the next night at AT&T Park, a short drive away from our hotel. Little did I know, booking the stay months earlier, we’d blow in amid “October Madness.”

We finally reached our destination: Encore Express Hotel, a.k.a. Music City Hotel, 1353 Bush St. Owned by a local rock musician, the hotel’s reputation and name derives from offering fully-equipped rehearsal spaces for local musicians to play in until 11 PM each night. We got a very reasonable rate considering this place brimmed with SF-style charm with original commissioned art throughout and musical instruments adorning the hallways and an actual trumpet hovering from the ceiling over each room entrance. We shared four bathrooms with other guest on our floor.

The Series-winning Giants crucially won all three of their home games while we were there, and the frenzied fan celebration spilled out like beer-foam lava all along, and into, bar-riddled Polk Street, right around the corner from our hotel. But the “music city hotel” has solid old brick construction and Giantmania didn’t disturb us in our room.

Speaking of “music city,” I imagine most people who’ve visited San Francisco have an indelible memory of the first encounter. Mine came flashing back, from the very early 1970s. My friends Frank Stemper, John Kurzawa and I inevitably visited Haight-Ashbury, which had just begun its slide into post-Summer of Love decrepitude, though it remains today.

The cover of The Grateful Dead’s new album “Workingman’s Dead” stood emblazoned atop the Fillmore West Auditorium, as a huge billboard. Where else but in San Francisco?

For two nights, we went to the legendary Fillmore, the multi-purpose basketball gym that was the nexus of the psychedelic San Francisco rock music scene. First we saw left-handed blues giant Albert King slinging his “flying V” guitar, with his honey-dripping-on-your-chin-stubble voice. The next night featured an early Southern redneck rock band called Black Oak Arkansas, fronted by a ratty-hired, white-trash Mick Jagger mimic named Jim Dandy, and an excellent blues-rock trio called Aum. Short-lived and undercredited, San Francisco-based Aum boasted distinctive vocal harmonies far from the same old-same old. Check out Aum’s album “Resurrection.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iZhkQb9tU5E

As Aum played, we stood on the far right side near the front. A woman was standing next to us whom we’d barely noticed. Then, at one point a man emerged from behind stage and walked up to the woman, who was smoking a joint. The ‘fro hairdo and the mustachioed dark looks were unmistakable: Carlos Santana. The woman apparently knew Carlos and was soon sharing her joint with him, right next to us. At one point, Carlos threw his head back, eyes closed, approximating the ecstasy of unleashing one of his patented guitar sostenutos. The joint never quite got over to the gawking Milwaukeeans.  The Santana band performing at Fillmore West ca. early ’70s. Note the basketball hoop in background at left, above guitarist Carlos Santana’s head. Courtesy nuevamusica clasica.blogspot.com

The Santana band performing at Fillmore West ca. early ’70s. Note the basketball hoop in background at left, above guitarist Carlos Santana’s head. Courtesy nuevamusica clasica.blogspot.com

A short time later, Santana went onstage to jam a bit with Aum. At one point, Santana announced, “I’d like to introduce you to a brilliant young guitarist. Come on out, Neal!” A skinny little 16-year-old white guy with another fuzzy hairdo came on stage with a Gibson Les Paul and started some mighty impressive riffing. His name was Neil Schon and he would go on to play in Santana’s band and become the lead guitarist with Journey.

But back in 2014 SF, we set out for Fisherman’s Wharf Several times we reached the precipitous crest of several streets with about 45 degree descents. Ann’s heart jumped up in her throat and dribbled there madly like a Harlem Globetrotter basketball. (We remembered why Hitchcock filmed Vertigo in San Francisco)

Ah, but I had faith in my Corolla, and it took the downhills like an Olympian. Still, this geography must be murder for people driving stick shift.

The Wharf is a gargantuan python of hawking and buying humanity uncoiling along the city’s ocean shore. It’s jammed with street-strutting seagulls, who seem to own the place (humans just visit or rent space), kitschy and funky historical distractions, alluring art galleries, steaming seafood and street musicians including a one man band-singer-drummer recalling Isaac Hayes on uppers. We saw a smattering of homeless folk, and some fishing docks. Strangely fascinating, though more commercial than I would’ve hoped.

But this is a great destination city and this one of its most famous attractions. A whole gift shop is dedicated to mementos of Alcatraz Prison, on the infamous island in the San Francisco Bay, also known as “The Rock.” It was a federal prison from 1933 to 1966, prompted by the Depression era of gangsters and prohibition. Amid various grainy, glorified photos and sometimes bizarre mementos of surly Al Capone and other notorious inmates, I fell for a funky refrigerator magnet, depicting a couple of prisoners trying to escape.

![IMG_0085[1]](https://kevernacular.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/IMG_00851-e1415731866163.jpg) We also visited Telegraph Hill, the city’s trademark high point, with its sumptuous picture-postcard views of the city. Inside iconic Coit Tower, the first floor bears a mural from perhaps America’s most enlightened era — the post-Depression WPA, which gave artists of all media new work, and gave America a renewed sense of self-defined, multi-cultural identity.

We also visited Telegraph Hill, the city’s trademark high point, with its sumptuous picture-postcard views of the city. Inside iconic Coit Tower, the first floor bears a mural from perhaps America’s most enlightened era — the post-Depression WPA, which gave artists of all media new work, and gave America a renewed sense of self-defined, multi-cultural identity.

Bernard Zakheim’s mural “Library” depicts fellow artist John Langley Howard crumpling a newspaper in his left hand as he reaches for a shelved copy of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital with his right. You see workers of all races shown as equals and the mural’s sometimes eccentric awkwardness gives it a class-free charm.

The misty aura of a moody afternoon in the Bay area hovers over beds of verdant beauty on Telegraph Hill. As a mysteriously sensual caller once requested of Dave Garver (Clint Eastwood), a disk jockey in nearby Carmel-by-the Sea: “Play ‘Misty’ for me.” Alcatraz Island is visible on the left, in the lower photo. Photos by Ann Peterson

The misty aura of a moody afternoon in the Bay area hovers over beds of verdant beauty on Telegraph Hill. As a mysteriously sensual caller once requested of Dave Garver (Clint Eastwood), a disk jockey in nearby Carmel-by-the Sea: “Play ‘Misty’ for me.” Alcatraz Island is visible on the left, in the lower photo. Photos by Ann Peterson

Saturday night we hooked up with my old compatriot from The Milwaukee Journal, Divina Infusino, and her longtime husband, ex-Milwaukeean Mark Schneider, for the ostensible raison d’être of our trip, the SFJAZZ Collective concerts at the SFJAZZ Center, the exquisite performance center built largely by inspiration from this group’s world-class talent and concept.

(Please see my full review of the SFJAZZ Collective’s Friday and Saturday concerts of originals and Joe Henderson music, which ends this travelogue, to be posted soon.)

Infusino, who’s written for Rolling Stone, The Huffington Post and other publications, has broad musical tastes, as does her husband Mark (formerly of Dirty Jack’s Record Rack, a pioneering Brewtown record store), but both are rock-oriented. Yet both were deeply impressed by the jazz collective.

Our post-concert drinks conversation got around to Divina explaining how San Francisco politics “realizes socialistic values as a reality rather than simply an ideal,” something that the SFJAZZ Collective exemplifies on its own multi-cultural terms. In this collective once again, jazz embodies a cultural template for our democratic way of life. A profound acknowledgment of talent meritocracy elevates their wedding to democracy, with high standards of processing and expression.**

The talk with Divina, the experience of “The City,” with its politically enlightened WPA murals and of that community’s extraordinary jazz collective led me to the Tocqueville quote that opens this part of the travelogue.

It struck me that the buzzing density of this compressed, yet ever-flowing city feeds the potency for a democratic environ that may well have evolved into viable socialist principles of shared struggle and growth, invention and potency — without betraying the American ideal of individual liberty. If anyone is an individual, it’s any given San Franciscan on the street, even if the saddest was a sunburned, probably homeless millennial, shuffling around near our hotel at 9 a.m. chugging a 36-oz. jug of beer. He stood uncertainly on the sodden side of bereft.

Perhaps inevitably, this fairly evolved city will betray signs of the messy democratic experiment, like America, where current polarization strains mightily for such closeness, likely a major reason for the sorry recent mid-term election results, reportedly the lowest voter turnout since 1942.

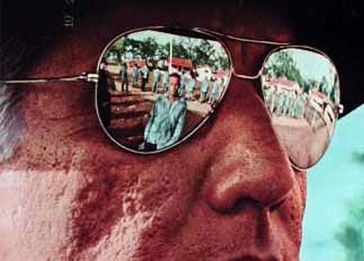

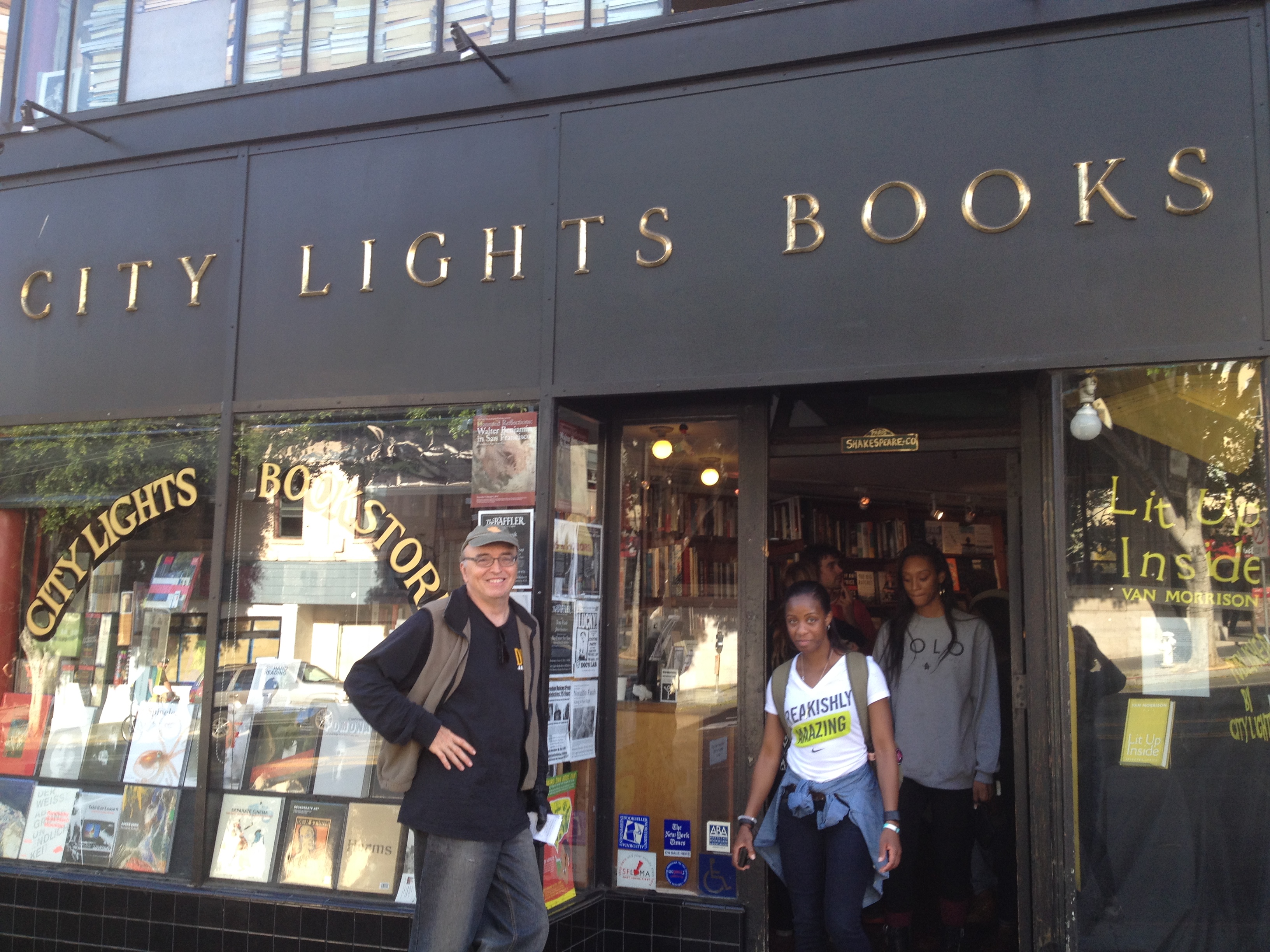

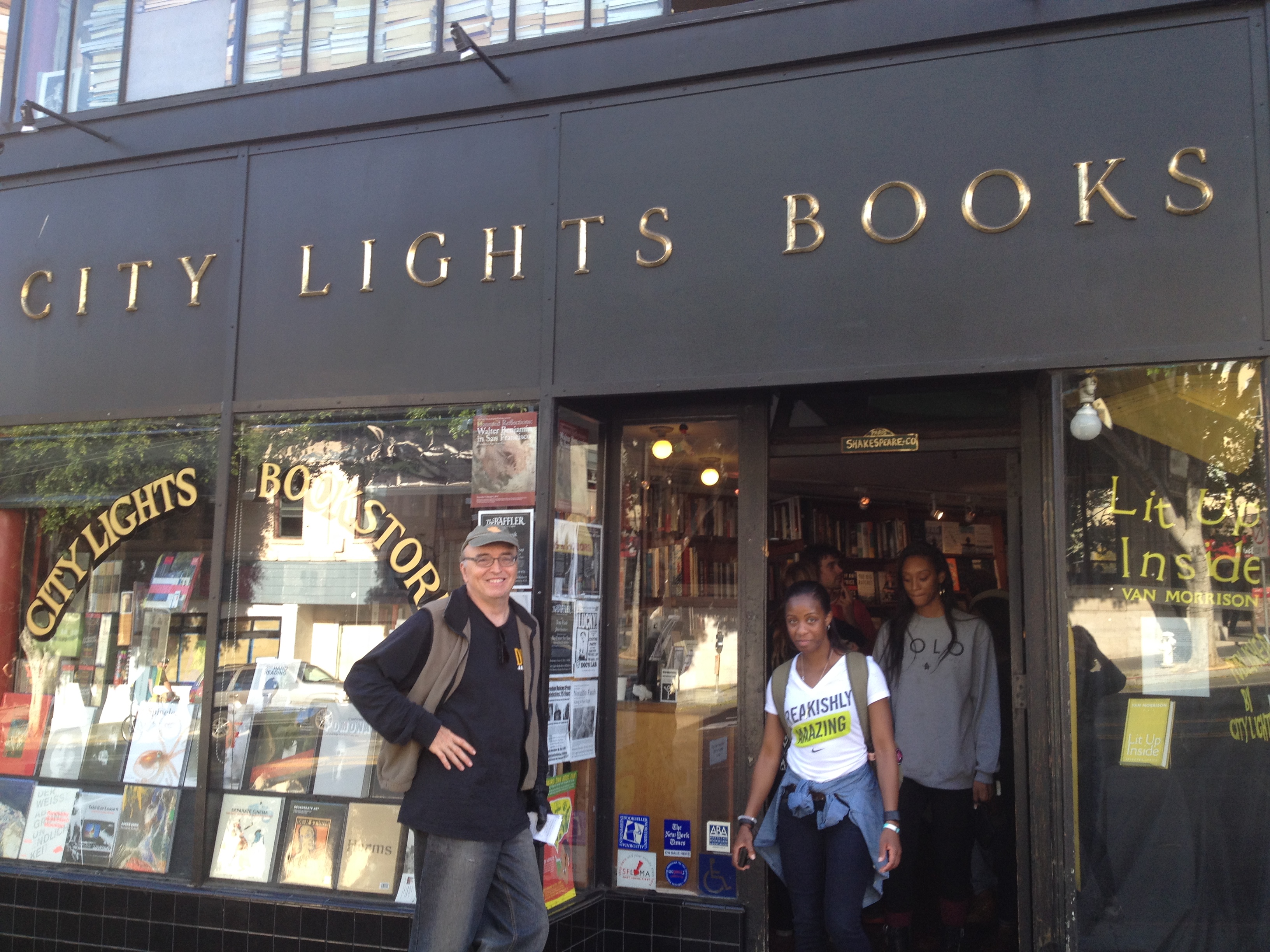

Finally, I must mention our trip to City Lights Book Store, which has morphed slowly over the years from a beatnik hole-in-the-wall, opened by poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti in 1953, into a three-story mother lode of literary wealth, and a publishing press, with as densely packed and as meaty an inventory of books as I have ever seen.  Kevernacular visits City Lights Bookstore. Photo by Ann Peterson

Kevernacular visits City Lights Bookstore. Photo by Ann Peterson

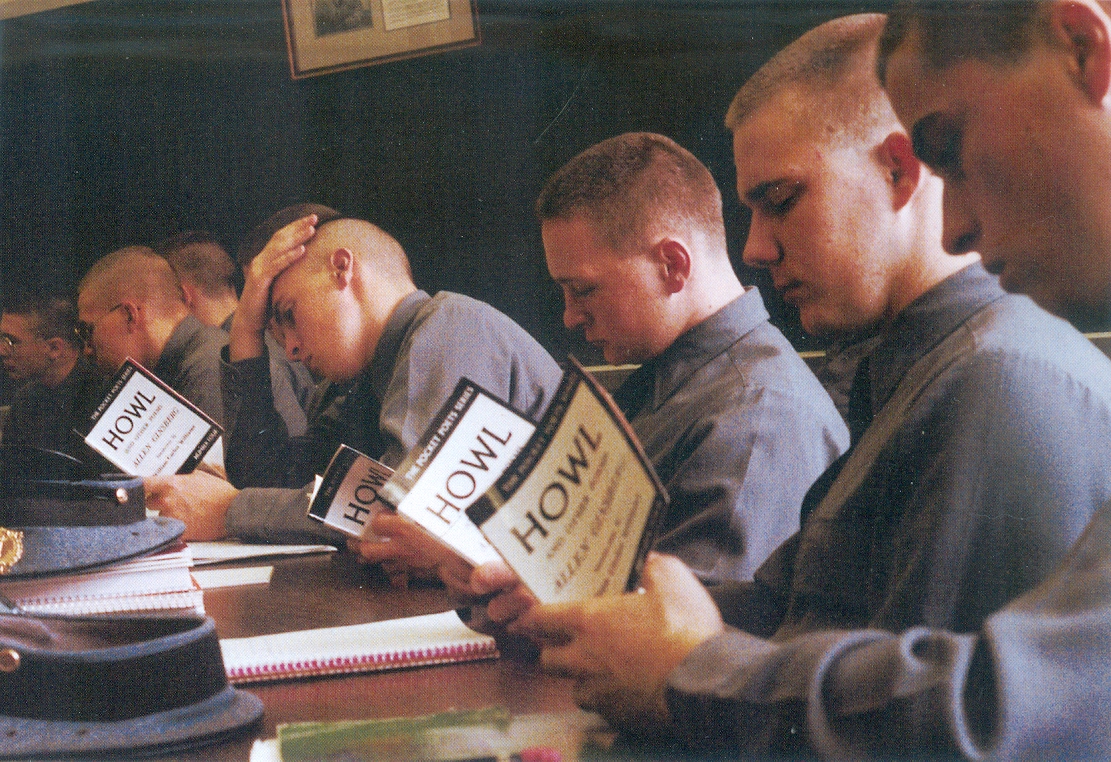

I easily could’ve bought the four or five books but I considered the overall expenses of my the trip. So I settled for only one, literary critic Raymond Williams’ Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, a sort of personalized, politically and culturally informed etymology of numerous significant words: from “aesthetic” and “alienation” to “welfare,” “Western,” and “work.” I also nabbed a fire engine-red City Lights T-shirt and a post card of one of the most incongruously delightful photos I’ve ever seen, of Virginia Military Institute students reading Beat poet Allen Ginsburg’s subversive masterwork “HOWL.”  Photo by Gordon Ball, copyright 1996 by Ball, and postcard copyright by City Lights

Photo by Gordon Ball, copyright 1996 by Ball, and postcard copyright by City Lights

Perhaps the City Lights success story affirms a viable synthesis of capitalist and socialist business strategies.

***

One more day awaited before we headed back east. I’d always loved the long surf and cliff-filled drive up Highway 1 with my pals, back in 1970. So, on a sun-kissed morning Ann and I drove across the Golden Gate Bridge into enchanting Marin County.

The Golden Gate Bridge on a sunny October day (above). Faithful travel partner and girlfriend Ann Peterson takes in the expansive romance of Highway 1, thirty-four years after I first did. Photos by KL

The Golden Gate Bridge on a sunny October day (above). Faithful travel partner and girlfriend Ann Peterson takes in the expansive romance of Highway 1, thirty-four years after I first did. Photos by KL

We wended our way through leafy hamlets that led to the great coastal highway, which deserves its top-of-the-list numbering, as if all of America’s potential laps up like the essence of natural resource, along the long and winding shore, right below our car wheels. We finally reached a small maritime museum that serves as headquarters for Point Reyes National Seashore, and its extraordinary peninsula — a half-hour drive away. This would be our final Westerly destination.

The thrusting geographic leg may extend further into the Pacific Ocean than any other point in the continental U.S. The remote shore locale is a playground of unfettered wildlife, at any given time: deer grazing nearby, elk herds at a fork in the road, seals on the rocky shore and California gray whales, beyond but often visible. After a few minutes of squinting into the ocean, I could’ve sworn I saw a gray whale break through the waves. But I didn’t swear to it. No doubt, however, about the gray whale skull mounted atop the dauntingly long staircase leading to the lighthouse.

A California gray whale skull (gulp) greets visitors at Pont de Reyes (upper photo). The actual lighthouse is situated down a 300-step flight of stairs (lower). Photos by Ann Peterson

A California gray whale skull (gulp) greets visitors at Pont de Reyes (upper photo). The actual lighthouse is situated down a 300-step flight of stairs (lower). Photos by Ann Peterson

The ancient Point Reyes lighthouse sits on a precarious tip of rock accessed by a 300-step descent, with breathtaking views down sheer cliffs to the roiling surf far below. The whole peninsula is windblown by a Poseidon with lungs the size of Minneapolis and St. Paul, and nearly as chilly. So leave your hats and your coiffure vanity behind. This bracingly beautiful westernmost point might have been the trip’s elemental high point.

***

On the long road back east, we stopped in Cozad, NE, home of The Robert Henri Museum, named for the founder of the famous American artist group “The Eight,” and a leading figure of the the “ash can” school of art. But the museum was closed for the season. Nevertheless it’s worth a visit.

Cozad was actually founded in 1873 by Henri’s father, a gambler and real estate developer. Henri was an insightful and sometimes provocative portrait artist, evidenced by this image of “Salome,” the disturbing biblical figure with a necrophiliac (or spiritual?) attraction to beheaded St. John the Baptist. Clearly Henri and other “ash can” artists like John Sloan and George Bellows broke far away from the era’s conservative American art academy, especially in their unprecedented depictions of gritty urban life and poverty. Henri also unleashed their clear impressionist influence to capture, with a swirling yet deftly poised brush, the still-brawny but penetrating vitality of post-industrial revolution America.

Robert Henri, “Rough Sea Near Lobster Point,” 1903 Courtesy earlywonder. wordpress.com

Robert Henri, “Rough Sea Near Lobster Point,” 1903 Courtesy earlywonder. wordpress.com

As I noted in a review of superb show at the Milwaukee Art Museum (which included Henri) in 2005 titled “Masterpieces of American Art 1770-1920,” such early modernist works capture “a profound American pride in its own character, natural bounty and largely Christian grappling with the sublime — matters that increasingly would inspire boundless envy, emulation and resentment. How wisely we learn from such arts revelations remains an urgent contemporary question.” 2

Again, I thought of Tocqueville’s insight about cultural-political dynamics and American potential, both waiting and wasted.

We promised ourselves a saner drive home and spent a few leisurely days back in Boulder, shopping, hiking and seeing the new Bill Murray movie St. Vincent, a tear-jerker but quite worthwhile to see Murray as a misanthropic Vietnam Vet. Our host, Kris Verdin, led us on a long hike with her dog Ella — a high-spirited Labrador-Hungarian Vizsla mix — up into the mountains near her home. Despite the current disabling neurological condition in my arms and hands, I tried a few climbing moves up a mountain face we reached. I felt my upper limbs protesting and refusing to secure me, so I meekly reversed myself. Cripes minnie manure!  Our Boulder host Kris Verdin’s irrepressible dog Ella (in the distant background on the trail) sometimes broke free to hurry our pace on a long hike up to the base of the Rocky Mountains. Photo by Ann Peterson

Our Boulder host Kris Verdin’s irrepressible dog Ella (in the distant background on the trail) sometimes broke free to hurry our pace on a long hike up to the base of the Rocky Mountains. Photo by Ann Peterson

Back on the road, we began making good time again. In fact, “The Man” busted poor Ann with a speeding ticket for driving 87 in a 75 MPH zone, after my g-force-pushing transgressions on the way out. The patrolman had me roll down my passenger-side window and, slightly intoxicated, I almost blew it by responding with my impersonation of “The Dude” Lebowski, which had just been entertaining Ann.

Chastened, Ann slowed into the descending darkness of Wyoming, and worried about the deer crossing signs. Ten miles down the road our headlights illuminated an animal form…standing smack in the middle of the Interstate lane strip. It was a coyote, and Ann slowed down. The scruffy canine peered at us, then scampered away.

“Whew!” she exhaled.

“Don’t worry about a deer, with that encounter odds are you won’t even see a deer,” I reassured her. I was right. However, another five miles down the road another Wile E. Coyote made another heedless display of his furry fanny, in the same between-the-headlights spot. We just missed him and all I could think of was the famous cartoon character plastered on a road.  Long-suffering Wile E. Coyote in arguably the funniest cartoon series ever, “The Roadrunner.” Courtesy zocalopublicsquare.org.

Long-suffering Wile E. Coyote in arguably the funniest cartoon series ever, “The Roadrunner.” Courtesy zocalopublicsquare.org.

Once I saw this video, I understood what our Wile might’ve been up to on the highway: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_9ieb1Y1VCY

Our last big stop was Lincoln, Nebraska, again, but a tad more highbrow than King Kong Burgers. The Sheldon Museum of Art, on the University Of Nebraska campus, featured a permanent collection including strong works by Jackson Pollock and his under-appreciated spouse Lee Krasner, Edward Hopper, Georgia O’Keeffe, Thomas Eakins, Mark Rothko, Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, and others.

A painting by Rockwell Kent (renowned for his 1930 illustrations of Melville’s Moby-Dick which helped popularize the book for modern readers) Headlands, Monhegan Island (see below) reminded me how the craggy, ceaseless shore seemed to haunt us (or at least me) with its serene, raging and mysterious moods, like a siren-spirit following us everywhere in a cloud of briny surf. A current Sheldon exhibit explored the experience and sensibility of Nebraska.

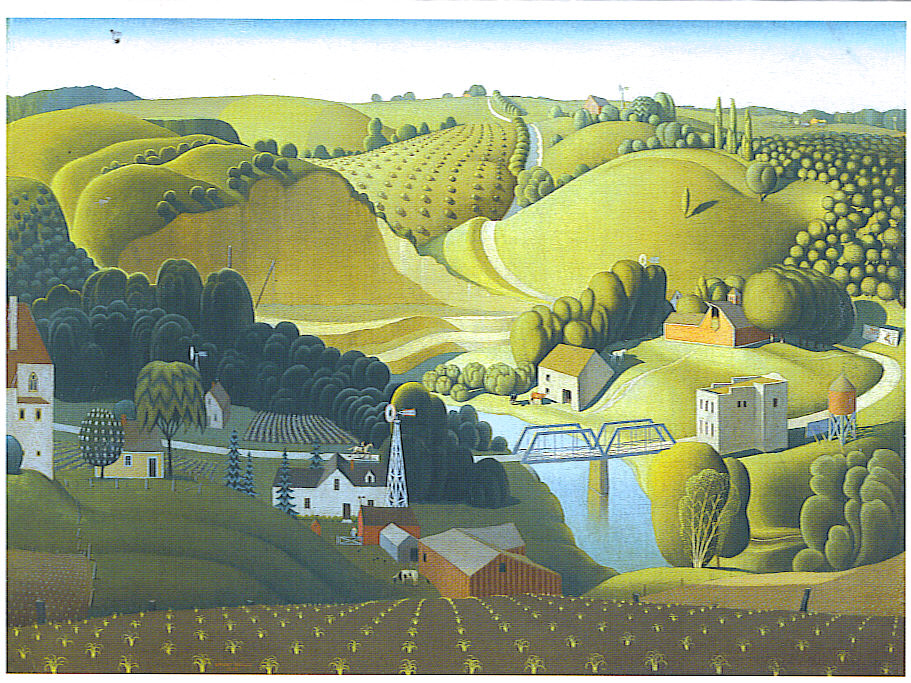

The Sheldon Museum of Art in Lincoln, Nebraska, offers a rich array of art, from classical to contemporary, including the welded steel sculpture by Michael Todd (upper image), the brooding shoreline by Rockwell Kent and Elizabeth Honor Dolan’s mixed-media maquette for the mural “Spirit of the Prairie” from the Nebraska Capitol Law Library, an intriguing and inspiring experiment in Americana. Photos by Ann Peterson and KL.

The Sheldon Museum of Art in Lincoln, Nebraska, offers a rich array of art, from classical to contemporary, including the welded steel sculpture by Michael Todd (upper image), the brooding shoreline by Rockwell Kent and Elizabeth Honor Dolan’s mixed-media maquette for the mural “Spirit of the Prairie” from the Nebraska Capitol Law Library, an intriguing and inspiring experiment in Americana. Photos by Ann Peterson and KL.

In that show, an 1930 experimental blend of oil pint, multiple paper layers and Masonite by Elizabeth Honor Dolan for a mural by “Spirit of the Prairie” at the Nebraska Capitol Law Library, depicts a bedraggled pioneer woman with infant in arm and faithful dog beside, which skirted Norman Rockwell sentiment with its daring stylistic ruggedness and the woman’s mute courage.

Outside, the bustling, friendly, red-emblazoned crowd and roaming bass band players defied the cold with sunny anticipation of the Nebraska Cornhuskers-Purdue Boilermakers football showdown later in perpetually sold out Memorial Stadium.

Ann and I began anticipating home. If the car courted internal chaos by the time we returned, the virtual kaleidoscope of memories, emotions and sensory impressions began settling into the places they would take in our cognitive and psychic history, and future.

The great American backbone rose behind us, its bristling glories, stories and mysteries intact.

________________

Editorial assistance by Ann Peterson, Kris Verdin, Edward Simon, Divina Infusino, Mark Schneider, Frank Stemper and John Kurzawa.

* The prototype for the SFJAZZ Collective is undoubtedly Joe Henderson’s 1966 Blue Note album Mode for Joe, a brilliant septet recording showcasing his originals and arranging, with a front line of Henderson’s sax, trumpet (Lee Morgan), trombone (Curtis Fuller), and vibes (Bobby Hutcherson). Hutcherson was also a founding member of the SFJAZZ Collective. The vibes are perhaps the band’s trademark instrumental component.

** The concept of socialism and capitalism as complementary or even symbiotic systems is discussed in an essay on the iconoclastic leftist writer Martin Sklar by James Livingston in the November 3, 2014 issue of The Nation, p. 27. Livingston argues that Sklar’s ideas are greatly under appreciated partly “because no one knows what to do with (their) revolutionary implications.” For example, after a certain point of production, capitalism has become superfluous as an inducement to work in production, Livingston writes.

Livingston also addresses the issue of how, in our capitalist-dominated system, socialism could be easily co-opted rather than become the proper corrective to capitalism’s excesses and ultimately needlessness to “economic necessity” — beyond profits that could not be “reinvested in productive ways.”

1. Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Ed. Harvey Mansfield and Delba Winthrop, University of Chicago Press, 2000, 432

2 Kevin Lynch, America’s Best: Show Spotlights Masterpieces from 1770 to 1920, The Capital Times, July 2001.

Outdoor photo of Fillmore Auditorium in 1970, courtesy wikipedia.

Like this:

Like Loading...

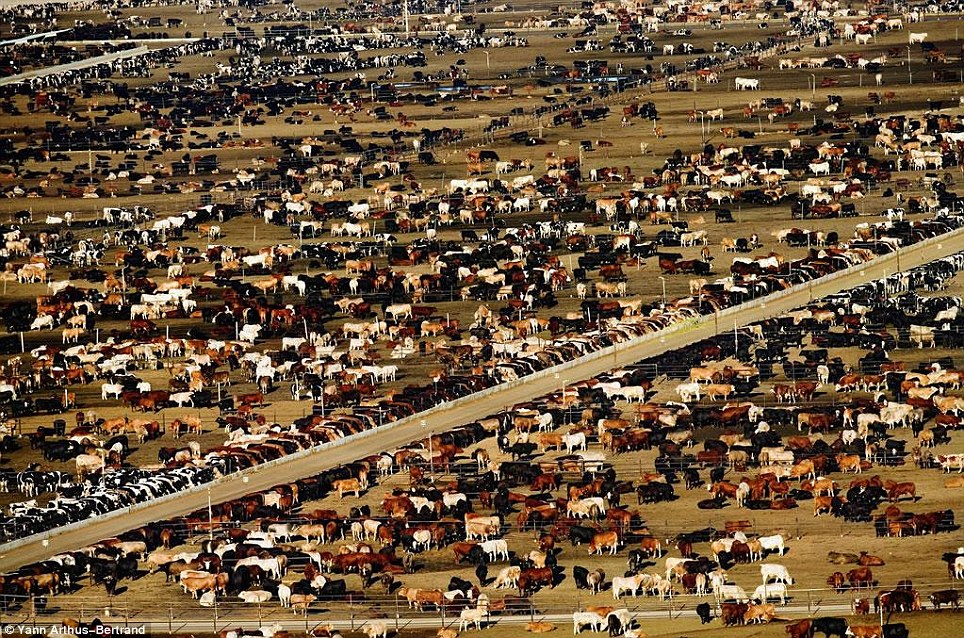

The quiet desperation of a beef factory farm. Courtesy kdur.org.

The quiet desperation of a beef factory farm. Courtesy kdur.org.

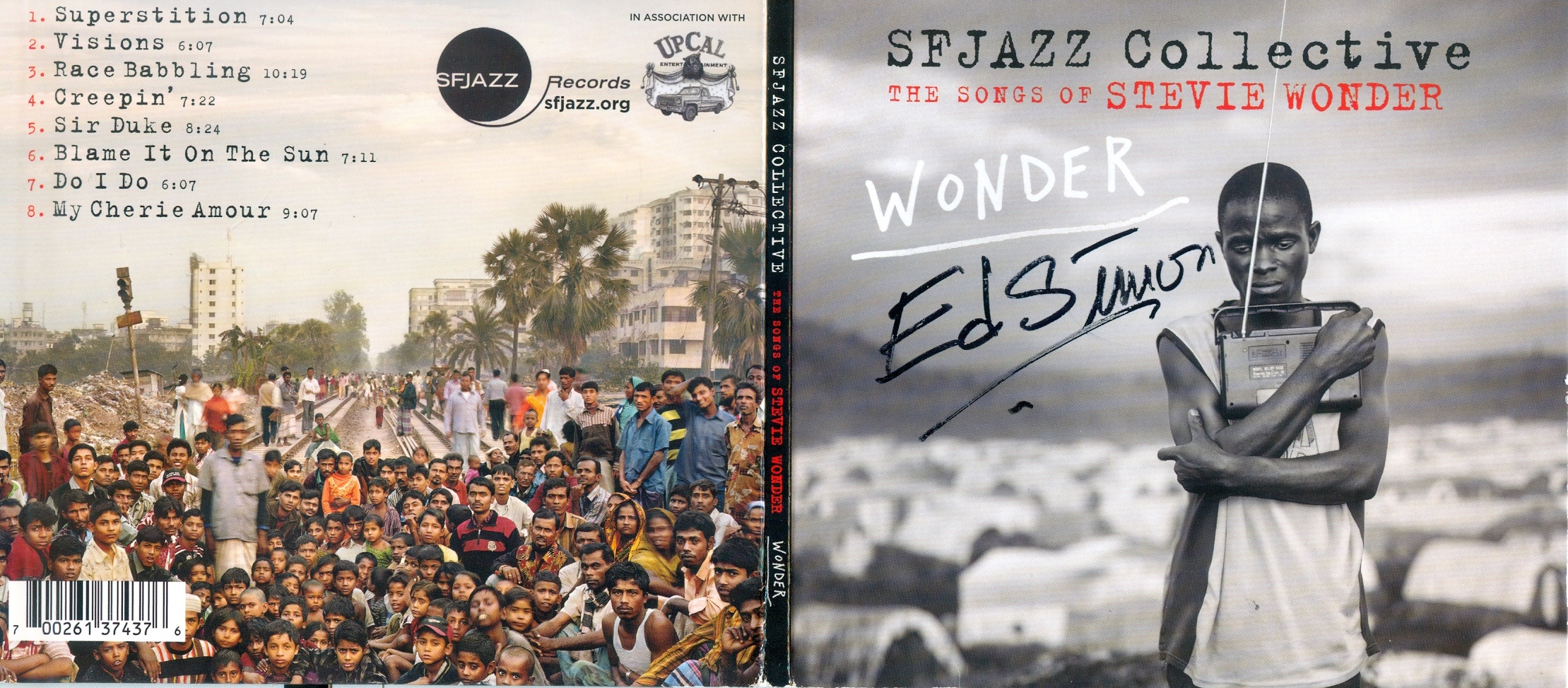

A copy of the SFJAZZ Collective’s NAACP Image Award-winning “Songs of Stevie Wonder.” The Collective’s pianist Edward Simon spoke with me after the concert and kindly signed the CD. Front and back CD cover photos by Joe Goldberg.

A copy of the SFJAZZ Collective’s NAACP Image Award-winning “Songs of Stevie Wonder.” The Collective’s pianist Edward Simon spoke with me after the concert and kindly signed the CD. Front and back CD cover photos by Joe Goldberg.  San Francisco from Telegraph Hill. Photo by Ann Peterson

San Francisco from Telegraph Hill. Photo by Ann Peterson “The Man with No Eyes” from “Cool Hand Luke.” Courtesy democraticunderground.com

“The Man with No Eyes” from “Cool Hand Luke.” Courtesy democraticunderground.com

The Santana band performing at Fillmore West ca. early ’70s. Note the basketball hoop in background at left, above guitarist Carlos Santana’s head. Courtesy nuevamusica clasica.blogspot.com

The Santana band performing at Fillmore West ca. early ’70s. Note the basketball hoop in background at left, above guitarist Carlos Santana’s head. Courtesy nuevamusica clasica.blogspot.com![IMG_0085[1]](https://kevernacular.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/IMG_00851-e1415731866163.jpg) We also visited Telegraph Hill, the city’s trademark high point, with its sumptuous picture-postcard views of the city. Inside iconic Coit Tower, the first floor bears a mural from perhaps America’s most enlightened era — the post-Depression WPA, which gave artists of all media new work, and gave America a renewed sense of self-defined, multi-cultural identity.

We also visited Telegraph Hill, the city’s trademark high point, with its sumptuous picture-postcard views of the city. Inside iconic Coit Tower, the first floor bears a mural from perhaps America’s most enlightened era — the post-Depression WPA, which gave artists of all media new work, and gave America a renewed sense of self-defined, multi-cultural identity. The misty aura of a moody afternoon in the Bay area hovers over beds of verdant beauty on Telegraph Hill. As a mysteriously sensual caller once requested of Dave Garver (Clint Eastwood), a disk jockey in nearby Carmel-by-the Sea: “Play ‘Misty’ for me.”

The misty aura of a moody afternoon in the Bay area hovers over beds of verdant beauty on Telegraph Hill. As a mysteriously sensual caller once requested of Dave Garver (Clint Eastwood), a disk jockey in nearby Carmel-by-the Sea: “Play ‘Misty’ for me.”  Kevernacular visits City Lights Bookstore. Photo by Ann Peterson

Kevernacular visits City Lights Bookstore. Photo by Ann Peterson Photo by Gordon Ball, copyright 1996 by Ball, and postcard copyright by City Lights

Photo by Gordon Ball, copyright 1996 by Ball, and postcard copyright by City Lights

The Golden Gate Bridge on a sunny October day (above). Faithful travel partner and girlfriend Ann Peterson takes in the expansive romance of Highway 1, thirty-four years after I first did. Photos by KL

The Golden Gate Bridge on a sunny October day (above). Faithful travel partner and girlfriend Ann Peterson takes in the expansive romance of Highway 1, thirty-four years after I first did. Photos by KL

A California gray whale skull (gulp) greets visitors at Pont de Reyes (upper photo). The actual lighthouse is situated down a 300-step flight of stairs (lower). Photos by Ann Peterson

A California gray whale skull (gulp) greets visitors at Pont de Reyes (upper photo). The actual lighthouse is situated down a 300-step flight of stairs (lower). Photos by Ann Peterson Robert Henri, “Rough Sea Near Lobster Point,” 1903 Courtesy earlywonder. wordpress.com

Robert Henri, “Rough Sea Near Lobster Point,” 1903 Courtesy earlywonder. wordpress.com Our Boulder host Kris Verdin’s irrepressible dog Ella (in the distant background on the trail) sometimes broke free to hurry our pace on a long hike up to the base of the Rocky Mountains. Photo by Ann Peterson

Our Boulder host Kris Verdin’s irrepressible dog Ella (in the distant background on the trail) sometimes broke free to hurry our pace on a long hike up to the base of the Rocky Mountains. Photo by Ann Peterson Long-suffering Wile E. Coyote in arguably the funniest cartoon series ever, “The Roadrunner.” Courtesy zocalopublicsquare.org.

Long-suffering Wile E. Coyote in arguably the funniest cartoon series ever, “The Roadrunner.” Courtesy zocalopublicsquare.org.

The Sheldon Museum of Art in Lincoln, Nebraska, offers a rich array of art, from classical to contemporary, including the welded steel sculpture by Michael Todd (upper image), the brooding shoreline by Rockwell Kent and Elizabeth Honor Dolan’s mixed-media maquette for the mural “Spirit of the Prairie” from the Nebraska Capitol Law Library, an intriguing and inspiring experiment in Americana. Photos by Ann Peterson and KL.

The Sheldon Museum of Art in Lincoln, Nebraska, offers a rich array of art, from classical to contemporary, including the welded steel sculpture by Michael Todd (upper image), the brooding shoreline by Rockwell Kent and Elizabeth Honor Dolan’s mixed-media maquette for the mural “Spirit of the Prairie” from the Nebraska Capitol Law Library, an intriguing and inspiring experiment in Americana. Photos by Ann Peterson and KL.

Ann Peterson posed with “”Harvest,” Tom Stancliffe’s 1999 sculptural rendering of Iowa’s important resources and icons, including corn, sunflowers, acorns, fish, hogs and books (detail below). It’s at the Cedar County Area Rest Stop and Welcome Center on I-80. Photo by Kevin Lynch

Ann Peterson posed with “”Harvest,” Tom Stancliffe’s 1999 sculptural rendering of Iowa’s important resources and icons, including corn, sunflowers, acorns, fish, hogs and books (detail below). It’s at the Cedar County Area Rest Stop and Welcome Center on I-80. Photo by Kevin Lynch  Photo by KL

Photo by KL  Photo by Ann K. Peterson

Photo by Ann K. Peterson At another point in Iowa we looked dumbfounded –at the longest truck rig I’ve ever seen, parked at a rest stop. The endlessly long white shape mystified us. Was it a portion for a gravity-defying Santiago Calatrava building? A wing for a giant stealth bomber? Further down the Interstate the wind blew the mystery away when — at another rest stop — we suddenly saw the identical form standing at proud, erect attention, seemingly scraping the sun. In a huge concrete and steel base stood a wind turbine propeller blade.

At another point in Iowa we looked dumbfounded –at the longest truck rig I’ve ever seen, parked at a rest stop. The endlessly long white shape mystified us. Was it a portion for a gravity-defying Santiago Calatrava building? A wing for a giant stealth bomber? Further down the Interstate the wind blew the mystery away when — at another rest stop — we suddenly saw the identical form standing at proud, erect attention, seemingly scraping the sun. In a huge concrete and steel base stood a wind turbine propeller blade.

Photos by KL

Photos by KL King Kong stands atop the sign for the fast food joint in Lincoln, NE named for him. The sign was too hot in contrast for this night photo to make out the words “KING KONG.” Photo by KL

King Kong stands atop the sign for the fast food joint in Lincoln, NE named for him. The sign was too hot in contrast for this night photo to make out the words “KING KONG.” Photo by KL The French were very big on the original “King Kong,” as this inspired poster by a French artist indicates. Courtesy highlight Hollywood.com

The French were very big on the original “King Kong,” as this inspired poster by a French artist indicates. Courtesy highlight Hollywood.com  Here’s Fay Wray, the “beauty (who) killed the beast.” Once, when I saw “King Kong” in a movie theater, Ms. Wray came on screen and a lecherous guy in front of me muttered to his companion, “What a dish.” Courtesy bobbyriverstv.blogspot.com

Here’s Fay Wray, the “beauty (who) killed the beast.” Once, when I saw “King Kong” in a movie theater, Ms. Wray came on screen and a lecherous guy in front of me muttered to his companion, “What a dish.” Courtesy bobbyriverstv.blogspot.com Kong fends off the airplanes atop the Empire State building, as epic a battle as the movies has ever given us. Courtesy highlight Hollywood.com

Kong fends off the airplanes atop the Empire State building, as epic a battle as the movies has ever given us. Courtesy highlight Hollywood.com With Kong’s blood streaming onto the Manhattan street, Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong in tuxedo, left), delivers his famous closing lines to the original “King Kong” (“Oh no,…”) courtesy bobbyriverstv.blogspot.com

With Kong’s blood streaming onto the Manhattan street, Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong in tuxedo, left), delivers his famous closing lines to the original “King Kong” (“Oh no,…”) courtesy bobbyriverstv.blogspot.com Patty Loveless’s rootsy bluegrass CD “Mountain Soul” courtesy of amazon.com

Patty Loveless’s rootsy bluegrass CD “Mountain Soul” courtesy of amazon.com Hard-working nurse practitioner Ann slumbered however, there at the story’s end, the passenger seat tilted back, her head against the plush bed pillow she’d brought along.

Hard-working nurse practitioner Ann slumbered however, there at the story’s end, the passenger seat tilted back, her head against the plush bed pillow she’d brought along.

Wyoming on Interstate 80. Photos by KL

Wyoming on Interstate 80. Photos by KL A trucker balls the jack through mountainous Wyoming highways. Photo by KL

A trucker balls the jack through mountainous Wyoming highways. Photo by KL

Suddenly a slightly tattered Motel 6 seemed like Nirvana. Courtesy blog.trekeffect.com.

Suddenly a slightly tattered Motel 6 seemed like Nirvana. Courtesy blog.trekeffect.com. An artist’s rendering of the The Donner Party’s hardships. Courtesy corvallistoday.com.

An artist’s rendering of the The Donner Party’s hardships. Courtesy corvallistoday.com.