I was dragged back to an old, troubling memory during my recent drive out to the West Coast. It arose again today when I read a review in The Book Review of The New York Times on Sunday.

I omitted this anecdote from my blog account of that journey because of the travelogue’s expanding length, and due to the unsavory nature of what I experienced — both on that westbound highway, and on an eastbound highway many years ago.

Now a new book compels me to share this, because the issues it raises are too important to ignore as the evidence, only a bit figuratively, stares back up at us from our dinner plates. Yet, the experience did not deter me from indulging in processed meats at least once more on the trip, at a restaurant in Lincoln, Nebraska. The accompanying photo reveals all, which I am now slightly ashamed of, though my facial expression is slightly self-mocking. I’m also aware of the irony of wearing a T-shirt from the culturally enlightened City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco.

If you are what you eat, did I know what I was, and how all that stuff got to be food? Photo by Ann Peterson.

As road partner and girlfriend Ann Peterson and I drove west, I don’t recall exactly where it was, probably Nebraska, but it felt like the middle of nowhere.

We smelled this nowhere before we saw it. Until then, the trip had been, among other things, a liberation from the foul smells and sights of urban pollution, and I rejoiced at having finally purchased a car with a sunroof, which let the pure air of America’s “Big Sky Country” surge over and into our car cabin as we sped down the highway.

Suddenly a skin-crawling odor infested our space, like a detour into hell on earth. For the living creatures we soon encountered, it surely must be.

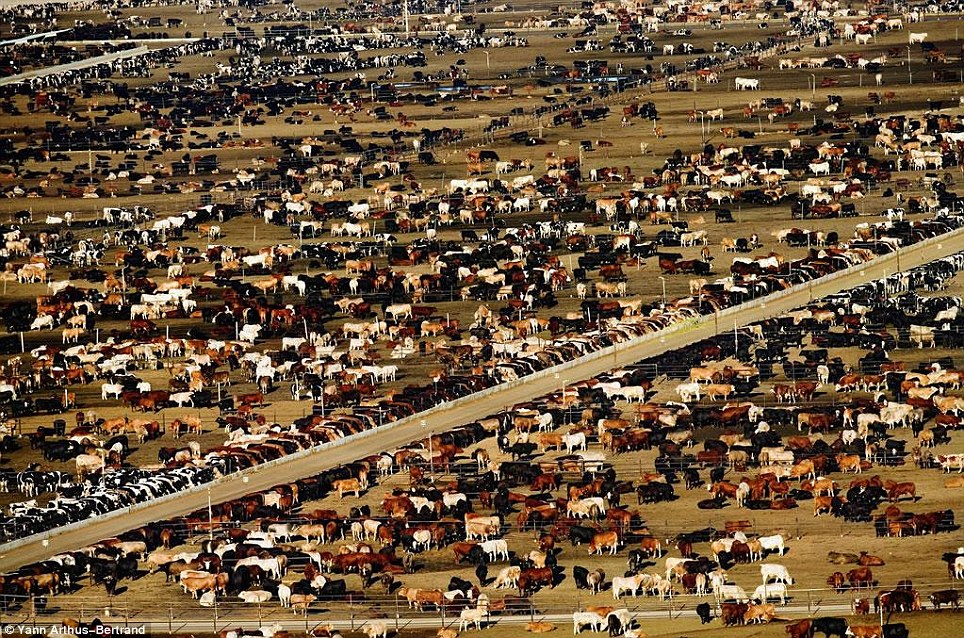

There on the right, we saw — acre after acre — hundreds of beef steer trapped in large pens. They all seemed just stuck, with nothing to graze upon but the muck — mired amid their own excrement — beneath their snouts, squishing between their hooves, splattering their hides, with meager hope of finding a few stray tufts of grass.

“It’s a corporate farm, for sure,” said Ann, who strives hard to be a vegetarian, precisely because of her moral and visceral revulsion at the act, the notion — and the massive, obscene business — of killing animals for human consumption, all too much of it, in mostly inhumane manners.

As she drove I looked on in increasing disgust and amazement. I never imagined the olfactory revulsion this experience triggered. (It strikes me that the adjective “olfactory” might be “Olefactory” in Spain, a play upon the bullfighter’s cry of “Ole!” shortly before he gores the bull — wedded to the function of a big meat-processing plant.)

The new book is called The Chain: Farm, Factory, and The Fate of our Food by Ted Genoways, from Harper/Collins. In ways it amounts to a historic updating of Upton Sinclair’s pioneering consciousness-raising investigative novel The Jungle, which exposed health violations and unsanitary practices in the American meatpacking industry during the early 20th century, based on an series Sinclair did for a socialist newspaper.

The stench of the corporate factory we encountered should be little surprise when one reads how Genoways argues that the industrial system behind “little cans of Spam” is “inextricably linked to a variety of social problems: animal cruelty, water pollution, foodborne illness, worker exploitation, a rise in anti-immigrant sentiment, government corruption and largely unchecked corporate power, “ writes reviewer Eric Schlosser.

“Once celebrated with some irony by Monty Python, ‘lovely spam, wonderful spam’ looms as a sinister force in The Chain, a hidden source of misery in the nation’s heartland.”1

So as we drove past the hoards of creatures crammed into those slovenly, infectious spaces, I thought of Henry David Thoreau’s famous quote: “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.”

It’s probably also true of such animals, although here they are somewhat free to express their desperation. Yet, after a point most probably stand silently waiting for their brutish destiny, emitting no more than heaving exhalations and, sometimes, an inconsequential snort, in mute resignation. Until the moment of truth.

In fact, Thoreau completed his thought with this sentence: “What is called resignation is confirmed desperation.”

The quiet desperation of a beef factory farm. Courtesy kdur.org.

The quiet desperation of a beef factory farm. Courtesy kdur.org.

So we left the slaughter farm behind with relief from our senses, but not from our sense of guilt, which made my Ketchup-slathered meatloaf on the trip back a week later, slightly gruesome, in retrospect.

Which leads me to old memory of a trip headed East from Wyoming to Milwaukee. I was hitchhiking back home after having flown out to The Grand Tetons one August of 1974, I believe, for a mountain-climbing trip in our nation’s greatest range of Alpine mountains. Hitchhiking home helped to offset the cost of the airplane ticket.

Perhaps I was lucky to not befall any misfortune on such a long journey dependent on the kindness of strangers. Except for the one occasion when a fellow gave me a lift and drop me off somewhere in Southwest Minnesota on Interstate 90. I dropped my hulking backpack on the roadside dirt and stuck out my thumb.

After a while, I stood there while hundreds of cars passed me, I felt a little forsaken, and lost, like befuddled Cary Grant, dropped off in the middle Indiana farm cornfields in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. Grant has a strange-enough encounter when a crop-dusting plane tries to do him in.

My experience was somewhat more subtle. A while after being dropped off, I began to hear strange noises. Aural hallucinations in the wind I thought at first. But there they were: strangled cries, almost human but not really, inarticulate, but high-pitched and clearly anguished. I turned around and for the first time noticed a long large warehouse-type building on the prairie, down an incline a short distance away from the interstate.

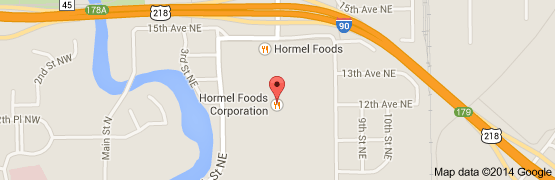

Strangely, I could see no sign anywhere identifying what the building as. It still didn’t hit me what I was hearing. Then, a short while later, I saw a large semi-truck coming from the east, slowing down right in front of me, but headed in the wrong direction. Now as the truck pivoted on to the a dirt road just west of me and trundled down it, I saw the red letters painted across the side of the truck: “HORMEL Foods.”

In that instant, I shuddered and my blood nearly froze — I understood I was hearing the death cry of hogs inside the slaughterhouse I stood in front of , like a fool witness to a crime.

I suspect there was an enclosed open space behind blank walls which allowed the pigs certain amount of freedom before their execution, thus the audible cries, unearthly yet as earthbound as any creature so fated. Now I wonder why I don’t recall smelling any stench. Perhaps the wind, blowing in the opposite direction, obscured it.

As Schlosser’s book review reports, Hormel has a major slaughterhouse in Austin, Minnesota.

So I looked on my road atlas, and after all these years, found the hellish spot where I had ignorantly stood: just outside Austin, Minnesota, right on Interstate 90, about 38 miles southwest of Rochester. Now it’s all the more incriminating that Hormel chose to not identify its slaughterhouse with any signage visible from the highway.

I am not making this up. Here’s a map with the Hormel location. wikipedia.com

Aside from its various pork based products, Hormel is the maker of the lowly and highly questionable but amazingly long-lived meat product SPAM. According to the most recent information I could find, Hormel saw its corporate profits rise in 2009 http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/22/business/22hormel.html?_r=0 by 3.7% from the previous year, and they totalled $80.4 million in profit, over 2008’s $77 million bottom line clearance. The recession clearly forced millions of middle class consumers to cut back on eating out which helped kitchen-table food manufacturers like Hormel. 2

Genoway’s illustrated book offers ample evidence about the sort of massacres endured by those pathetic hogs in Minnesota and those stoic steer in Nebraska, how their hide and flesh are stripped and their entrails extracted from their fracturing skeletons.

There is no pretty way to put it, and that would only be evasive euphemism. This is why even though I have some chicken breasts in my freezer, I suspect I will move ever closer to vegetarianism, even though I still believe the vitamins and protein of meat is an important part of a healthy, balanced diet. But I rarely eat red or ground meats, and will strive to avoid especially mammal meat.

I will try not to judge others in their dietary choices although it is difficult not to feel certain pangs of regret and remorse for the type of diet that has led so many of Americans to obesity and to death, from coronary issues.

And there is a more directly human issue haunting his book — “The poor treatment of slaughterhouse workers who lead impoverished lives.” Genoway tells us how “poor immigrant workers are treated only somewhat better than the hogs at a Hormel slaughterhouse.” Genoway depicts the lives of these workers “with great skill and compassion. Those who remain healthy are driven to cut meat at ever-increasing speeds; the injured are harassed, bullied and forced out of their jobs ‘I feel thrown away’ one worker says. ‘Like a piece of trash.’”

And of course, regarding Pres. Obama’s recent immigration reform executive action, many undocumented immigrant slaughterhouse workers live in fear, elected to report violations of the labor code. I’m also acutely attuned to a workplace menace the book reveals called ”progressive inflammatory neuropathy.” I suffer from an inflammatory neuropathy that is also an autoimmune, although thankfully mine — likely the result of an errant flu shot — is not progressive.

But the slaughterhouse workers’ disease include symptoms of quote pain, fatigue, headaches, nausea, numbness of limbs and partial paralysis. Investigators from the Mayo Clinic and the Minnesota Department of Health Centers for Disease Control and Prevention determined that, as Genoway explains, “Some one of the chain of command, someone at Hormel, had found a buyer in Korea were liquid pork brains are used as a thickener in stir-fry.

“To meet the overseas demand, workers use compressed air hoses to liquefy hot brains, standing at the ‘head table’ for eight hours or more each day, inhaling the fine pink mist. Once it seemed clear that inhaling dismissed could produce neurological damage in human beings, machines were shut off. But the workers affected by the new disease had to fight for medical benefits and some of those too sick to continue working got financial settlements only by threatening to sue.

Genoway explains: “After attorneys fees, each received $12,500, one-half year’s pay.’”

Schlosser notes that a book like The Chain “may induce smugness among lifelong vegetarians.” But he reports that migrant workers who harvest America’s freshest fruits and vegetables earn wages even lower than those of meatpacking workers, and also suffer debilitating injuries on the job.”

So again, it comes down to a brutish, inhumane profit-driven corporate culture of food gathering and processing. Schlosser also asserts that Genoway’s book “does a better job of portraying “the impact of the food-processing system on the people at the bottom, the destruction of rural communities and the backlash of racism” than does another fine book published this year, The Meat Racket by Christopher Leonard.

Of course, things are changing for the better. Implicit consciousness of the pervasive abuse of humane processing practices has even extended to mainstream supermarkets, where you can often find meat that’s labeled as humanely raised and processed. Alternative, health food stores such as Whole Foods and, in Milwaukee, the wonderful Outpost Food co-ops, have flourished in recent years as consumers become more aware of healthy eating and food production practices.

We even see now a paleolithic food diet movement, which essentially eschews the whole concept of farm-produced food of virtually all types, in favor of a diet of naturally-occurring foods that predate modern farming, or a so-called “hunter and gatherer’s” diet.

Schlosser concludes hopefully: “An outraged public, a refusal to ignore the exploitation of the poor, a willingness to confront powerful vested interests, a desire to expel the influence of money from politics – a movement characterized by all these things in force 100 years ago, (after Sinclair’s The Jungle appeared) and within a generation achieved its principal aims.

With more books like The Chain, more anger, knowledge and compassion, I see no reason that history can’t repeat itself.”

Perhaps the change begins with the choice we make in the food market, with what we choose to cook and place on our dinner plates. It’s a challenge that even braces against our cherished holiday of Thanksgiving this week. I suspect I will eat some of my sister’s succulent turkey, but after my long road trip, I am now chastened and wiser.

_______________

1 Eric Schlosser, “What Goes In, What Comes Out,” a review of The Chain: Farm, Factory, and the Fate of our Food by Ted Genoways, The New York Times Book Review, November 23, 2014, 28

2 http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/22/business/22hormel.html?_r=0

Photo of corporate beef farm courtesy of generationawakening.com

Photo of hog pens courtesy of planetoftheanimals.blogspot.com

Photo of hamburger courtesy of reformedmascot.blogspot.com