Almost exactly two months before my June 11, 1986 interview with pianist Cecil Taylor, he’d been in Berlin performing solo, and recorded for what became his next album, For Olim, on the Italian Soul Note label. The concert was for the “Workshop Freie Music 1986,” a festival of improvised music. I just now realized that time frame, and consider how that might illuminate our remarkable interview. I’m taking care to think of temporal matters, as I don’t laugh off non-scientific things like numerology.

And now that Cecil has died, which changes many things, some small details grow in magnitude. As I mentioned in my previously posted Taylor appreciation, he was born in March 25, 1929 in Long Island. My father, who had a similar interpersonal warmth, was born less than 4 months later, July 20, 1929, on the opposite American coast, in Seattle. Norm Lynch first spurred my interest in music with his love of jazz and classical music, and his favorite jazz artist was composer/arranger bandleader Stan Kenton, whom classically-trained Taylor also held in high regard.

I certainly felt a connection to Taylor when I met and interviewed him that summer. And I was stunned when, after the interview, our mutual friend Ken Miller persuaded him to fly to Milwaukee to merely visit, a place he may never have been to, though he did teach at the UW-Madison for several years in the early 1970s. Perhaps Cecil was coming out of the grief and mourning of having lost the musician closest to him, longtime Unit member and saxophonist Jimmy Lyons, who died in May 1986, the month right between his For Olim concert and our June interview (The For Olim album is dedicated “To the living Spirit of Jimmy Lyons”).

***

Which brings me to say that, though I have nothing but fond memories of him, I don’t want to paint Taylor with a hint of a Pollyanna patina. That first teaching gig of his in UW Madison’s music department revealed how Taylor could be a difficult person.

I know not much of that period of his life, aside from my very first Taylor concert experience – seeing him perform solo at UW-Madison’s Mills Concert Hall. I was in the third row, and I could almost feel his leaping, cougar-like muscles, his flying sweat. This was an astonishing revelation of the potential of live music performance, something that could easily encompass, music, dance and athletic feats, like playing a full game of competitive basketball (I easily imagine the small, wiry Taylor as an Allen Iverson-style point guard; he typically wore athletic garb for his performances). He played this concert without his nearly ever-present glasses, so his extraordinary physical dynamism and intensity led to an almost comical circumstance. 1, 2 His black knit cap repeatedly slipped down over his eyes and he would play blind for several minutes at a time, before easing the pace and allowing himself to push the cap back out of his eyes.

Once of the mysteries of Cecil Taylor was that he lived to be 89 while being a life-long cigarette smoker. However, the rigorous athletic lifestyle he otherwise kept probably contributed to his longevity. Courtesy jazzbluesnews.space

And the UW is where he met Ken Miller, the dancer with whom Taylor would form a deep, lasting bond, and who became the first person to ever dance with the Cecil Taylor Unit.

However, it’s a matter of history that in this teaching position he controversially flunked two-thirds of his final music class. I think the extraordinarily high standards that he set for himself, he also expected or hoped of others, especially his students. At UW, I suspect he was still learning how to maintain reasonable rubrics of instructional expectations. After all, he did live in The World of Cecil Taylor (as one of his first albums was titled) which was a profound, wide-ranging and sometimes mysterious realm.

And I know, from first-hand experience as a recent graduate student and teaching assistant, that even today it’s easy for professors – at large universities where research expectations are valued more than teaching – to elide the clarity of set rubrics, in the name of “academic freedom.” But students can be left groping, without proper benchmarks for a good grade.

Madison jazz pianist Jane Reynolds, who did a PhD dissertation on Taylor, says the UW music department stopped allowing Taylor to use their pianos because they thought he was damaging them. “That pushed him over the edge,” Reynolds says. Taylor soon left UW, with Ken Miller, for a teaching position at Antioch College. He later also taught at Glassboro State College in New Jersey.

***

I digress: Taylor’s 1987 Milwaukee trip had no prospect of a gig or payment, only socializing, hosted by Ken, a dear old friend. Cecil and Ken came to my home for dinner and attended a reception in Taylor’s honor, the real centerpiece of the visit, filled with many musicians.

Cecil Taylor greets fans at a reception held for him at the Wisconsin Conservatory of music in Milwaukee in 1987. His long-time friend and collaborator Ken Miller, who organized the event, sits directly to his left.

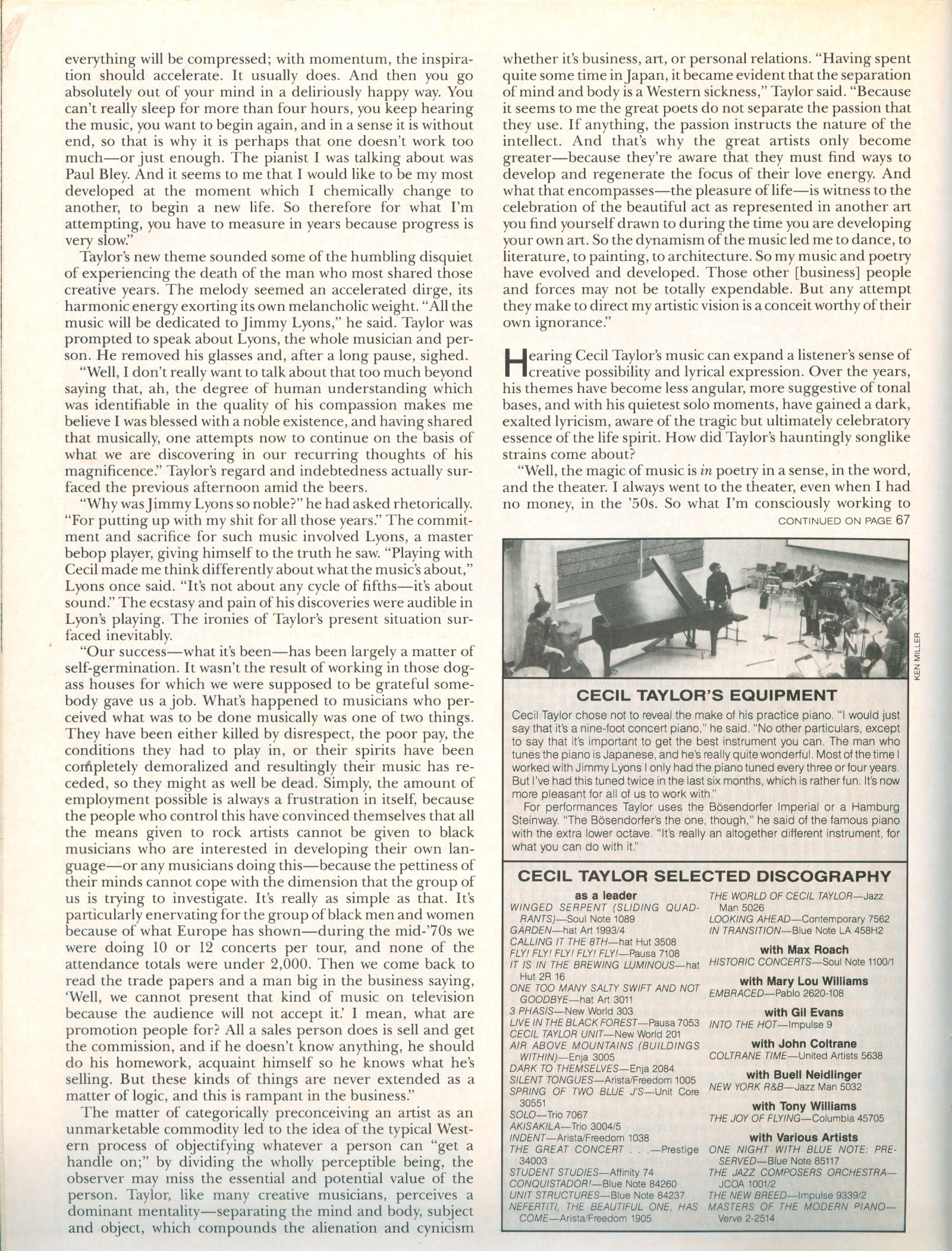

Pardon the personal indulgences. But my welter of feelings and thoughts upon his death last week finally focused on the realization that posting that 1986 interview was a very logical extension of the remembrance I wrote. The interview is, among other things, sort of the soul of my relationship with Cecil Taylor, such as it was. I reported and wrote it for Down Beat magazine, but it was held in his front practice room, on the second floor of his three story townhouse, beside his grand practice piano. He would not reveal the brand of that piano, perhaps because he didn’t want potential thieves assessing is value. He had good reason being wary, partly because he knew he was a naturally gregarious person who might easily be hustled. This indeed happened late in his life, when a contractor he thought of as a friend bilked him out of his $500,000 Kyoto Prize, though the man was later exposed and arrested.

When I interviewed him, Cecil talked well into the second of two 90-minute cassette tapes I had with me. I’ve never needed, before or since, more than one 90-minute tape for an interview of an artist. 3 Again, the numbers suggest something about the nature and quality of the conversation. It mainly reflects Taylor’s thoughtful, poetic eloquence, his extraordinary, quicksilver mind which took surprising tangents but usually tied them together in his own distinctive way. I hope the interview as published conveys the best of that talk, although much was edited out. (More commentary and photography below, after the magazine interview)

The cover of Taylor’s 1987 album “For Olim,” was among his most acclaimed of many solo piano recordings. The triple-exposure photo by Ken Miller aptly characterized Taylor as an embodiment of the title’s meaning. On the back cover is this explanation: ” *Olim – An Aztec hieroglyph meaning movement, motion, earthquake.” Album Photo by Ken Miller, courtesy Soul Note IREC.

What also presses greatly on my memory and heart now is Ken Miller, a nearly forgotten man who died in his mid-40s of respiratory illness. His death crushed me, as I was by then working in Madison and had lost touch with Ken in the pre-social media era. He was a sweet, gifted and remarkably wise man who, more than any other friend, helped me through my tumultuous first marriage. He helped counsel Taylor through his teaching career and far beyond. He was also a talented cultural facilitator and promoter, photographer and visual artist.

His brilliant photos of Taylor, taken in the pianist’s Milwaukee hotel room, also inspired a promotional campaign for Polygram Special Imports, the company that distributed the Soul Note label of Taylor’s recordings at the time. The promotion included a “Jazz Mount Rushmore” motif built around Miller’s iconic cover photo of Cecil on For Olim. I was among the jazz journalists who received unsolicited a sweatshirt and a large promotional pin. A nifty marketing strategy, however Ken Miller knew nothing of it until I told him of the promotion items using his superbly sculpted portrait (see photo below). He later said he never received any compensation for their artistic liberties with his intellectual property, unlike DownBeat which paid for in their original use of his photographs

Photo of Polygram Special Imports promotional items by Kevin Lynch

I believe part of the reason Ken Miller died so young was that he was a financially struggling artistic black man who didn’t get the proper medical treatment he needed. I always wanted to talk to Cecil about this, but when I finally phoned him, late in his life, he never called back. I sensed that the subject of Ken it may have ventured into private matters. They were both gay men, but Taylor, born in the Great Depression, survived partly by staying in the closet until the 1980s, when he was outed by a conservative journalist who also played drums and had an ax to grind, because Cecil did not let him play in The Unit.

I suspect Taylor’s strong private side reflected his generation’s struggle with sexual politics, like other great gay jazz men – pianist-composer-aranger Billy Strayhorn, born in 1915, and singer-songwriter/pianist Andy Bey, 10 years Cecil’s junior. Only now, of course, are we addressing important issues like marriage and gender equality, in a nation where we profess that “all men (and women) are created equal.” I believe that, had they both been born later, Ken and Cecil would’ve become legal partners. Only one of them lived anything close the expectancy of a full life, and Cecil’s was lived uphill most of the way, outperforming white men and virtually everyone, to finally gain, as an old man, honors with financial rewards.

Now, I also recall of my day with Cecil, several cats roaming his home, and a poster on his practice room wall of Chicago multi-instrumentalist and composer Joseph Jarman (best known as a member of the Art Ensemble of Chicago) looking down on us. The Jarman poster now seems more significant, again for temporal reasons. The Art Ensemble’s artistic motto was “Ancient to the Future.” If any other musician, outside of that ensemble, embodied the motto’s values, it was Cecil Taylor. His vision traced our culture’s past and unfolding future and, we hope, vitality. He studied and understood the genius of ancient non-Western cultures and hovered like, a great American eagle, his wings helping illuminate – by directing sunlight with shadow, back and forward – a long road less-traveled.

And that has made all the difference – for sure at least, an incalculable difference.

______________

- Among the giants of new thing jazz in the 1960s, Cecil was about the only one who wore glasses, as he was quite nearsighted and a voracious reader and not uncoincidentally perhaps the most overtly intellectual. However, a comparable case could be made for Archie Shepp, who didn’t wear glasses to perform, but was the first black saxophonist to record with Taylor (soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy – a Russian-American Jew who, like Taylor, loved and worked with poetry – played on his recording debut in 1957). Another avant-garde contemporary of Taylor’s of far less renown, who was comparably bespectacled, was trumpeter Bill Dixon. Among the few other bespectacled great musicians of that generation, but hardly an avant-gardist, was pianist Bill Evans. Yet, in a far quieter way, he was a great and influential innovator.

- Among the next generation of jazzers, baby boomers, trumpeter Woody Shaw is one of very few who performed with glasses, also clearly a strong prescription. Woody also was a deep, heady musician and – as a younger baby boomer trumpeter and jazz scholar, bespectacled Brian Lynch, has shown in recent years – a musician still underappreciated for his innovations. (This p.s. shouldn’t be misinterpreted as picking on near-sighted musicians, as I myself have a comparable strong prescription.)

- I listened again to the very beginning of the recorded Cecil Taylor interview, and had forgotten that the first thing Taylor does, after greeting me and offering me some fruit juice, was sit down and play a typically powerful, repeated, two-handed Cecil Taylor etude figure on the piano — my very own mini-Cecil Taylor bootleg! And he knew I was recording already. Critic Whitney Balliett was so right about his desire to share his music. Why else would he typically played well past when most people would drop over from exhaustion?

A very interesting piece about a remarkable man, thank you. However I am astonished that you seemed to ignore Cecil’s true passion at the U of W Madison which was the Cecil Taylor Ensemble (aka. The Mendota Players,) of which I was the bass player( featured rather prominently in the photo in your Downbeat article.)

We all worked together some five hours a night, six and seven days a week for the entire year. I remember quite vividly the first time Ken Miller joined us, (nothing to do with the Unit at that point.) We went on to perform at Hunter College in NYC and Antioch College both in that year, road trips for the ages.

I am not sure how you missed this chapter which I think greatly expanded Cecil’s capacities as a composer.

Hmm

Dear Jeff Crespi, Thank you very much for your comments and for filling me in about the UW incarnation of The Unit (aka The Mendota players, interesting). I did not choose to ignore Cecil’s time in UW. I did describe my experience of seeing him perform solo there. Unfortunately I never knew anyone who had played music with Cecil at UW, and Ken Miller is sadly long gone. So I didn’t have a lead on that. My apologies for not tracking you down. But I hadn’t known of you either, until now. If you don’t mind, I’d like to add your comments (and a bit of my response) to the bottom of the actual text of the post, so more people see it. Let me know if that’s OK with you. Also tell me if you’re still musically active. my e-mail is kelynchmi@gmail.com

Thanks, Kevin