Courtesy bluenote.com

Blogger’s note: On Aug. 7, I will add to this posting a more complete review of Charlie Haden’s last released recording “Last Dance,” when it is published by The Shepherd Express.

On the new ECM CD, Last Dance with pianist Keith Jarrett, Charlie Haden’s extended bass solo on “Where Can I Go Without You?” magnificently extends the melodic contours and the meaning of the song, as if he has deposited the questionnaires directly in the heart of the listener.

Yet his epitaph might be another standard, “Everything Happens to Me.” Not as a solipsistic whine, this was a humble man. Rather, this musician lived a remarkably full creative existence, embracing all life’s wonders, cruelty and strangeness with his artful gifts and passion for justice, while battling the infidels of his body and spirit, to the end.

“I want to take people away from the ugliness and sadness around us every day and bring beautiful, deep music to as many people as I can,” Haden said in a 2013 Interview with the Associated Press shortly before receiving his lifetime achievement Grammy Award. Eventually his body, debilitated by post-polio syndrome, took his music and life from him.

Born on August 6, 1937 in Shenandoah, Iowa — Charlie Haden died at age 76, on July 11, shortly after the CD’s release. This great bassist, composer, educator and bandleader has a vast and wide-ranging recorded output (see selected discography below), from powerfully rhetorical, politically acute large-group records to duets, where you hear the man most intimately, which is why I am starting this appreciation with a consideration of his duet recordings with several different pianists.

Keith Jarrett and Charlie Haden recording the sessions that produced “Last Dance” and “Jasmine.” Courtesy npr.com

Besides Jarrett, Haden also recorded excellent duet albums with pianists Denny Zeitlin and Hank Jones, actually two superb recordings with the latter — of spirituals, hymns and folk songs, which reveal some of his roots as a boy singer in the popular country radio act The Haden Family.

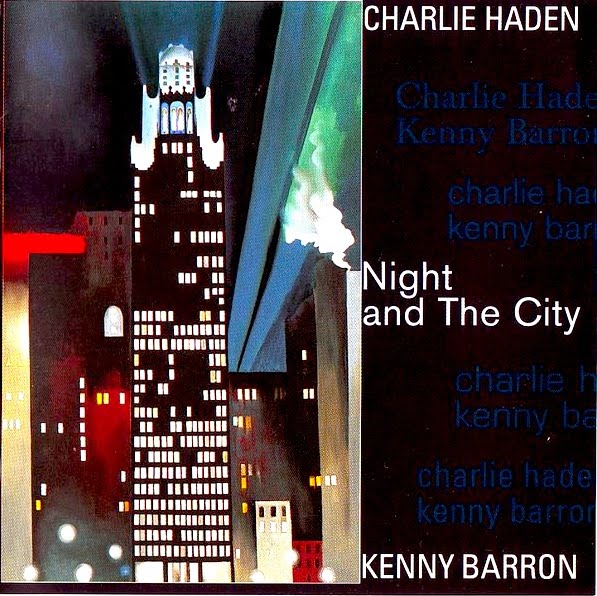

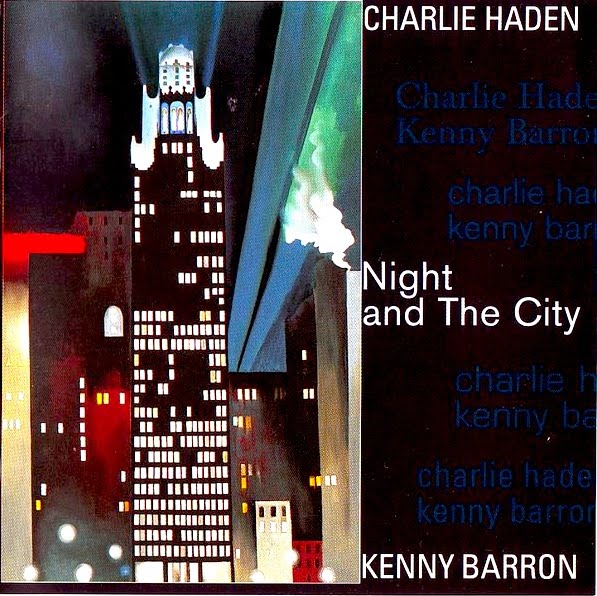

But Haden’s most artfully beautiful duet album was Night and the City with the master of New York piano jazz, Kenny Barron. Haden the role player understood restraint and understatement, and knew, with a pianist of bounteous pianistic and harmonic resources like Barron, the bassist can slip a bit further into the background. Yet Haden remains the recording’s deep-breathing presence, the knowing inner voice perhaps weighing the difference between the dark and light angels within each human, for this is a musical symbiosis of two sensibilities as one whole.

Haden’s “Waltz for Ruth” from Night and the City: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3gbhHA_nrEY

The CD’s cover image, Georgia O’Keeffe’s famous 1927 painting “Radiator Building – New York” is the perfect visual analog to Haden’s heartland-to-big city career arc. O’Keefe, a Sun Prairie, Wisconsin native, became the student and spouse of New York sophisticate art photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who understood her genius, here interpreting the ultimate urban setting.

The cover of “Night and the City” with Georgia O’Keeffe’s painting of the Radiator Building in New York. Courtesy blue-train.es

The painting’s architectural starkness parallels Haden’s stripped-down structural strength, the dancing wisp of smoke suggests his lyricism, and the lights reaching to the heavens, his spirituality. The music echoes not only O’Keeffe but also the poem quoted in the liner notes, Mark Strand’s “Night Piece,” which itself pays homage to Charles Dickens:

…And people moved like a ghostly traffic from home to work

and home,

and the poor in their tenements speak to their gods

and the rich do not hear them, every sound is merged,

this moonlit night, into a distant humming, as if

the city, finally, were singing itself to sleep.

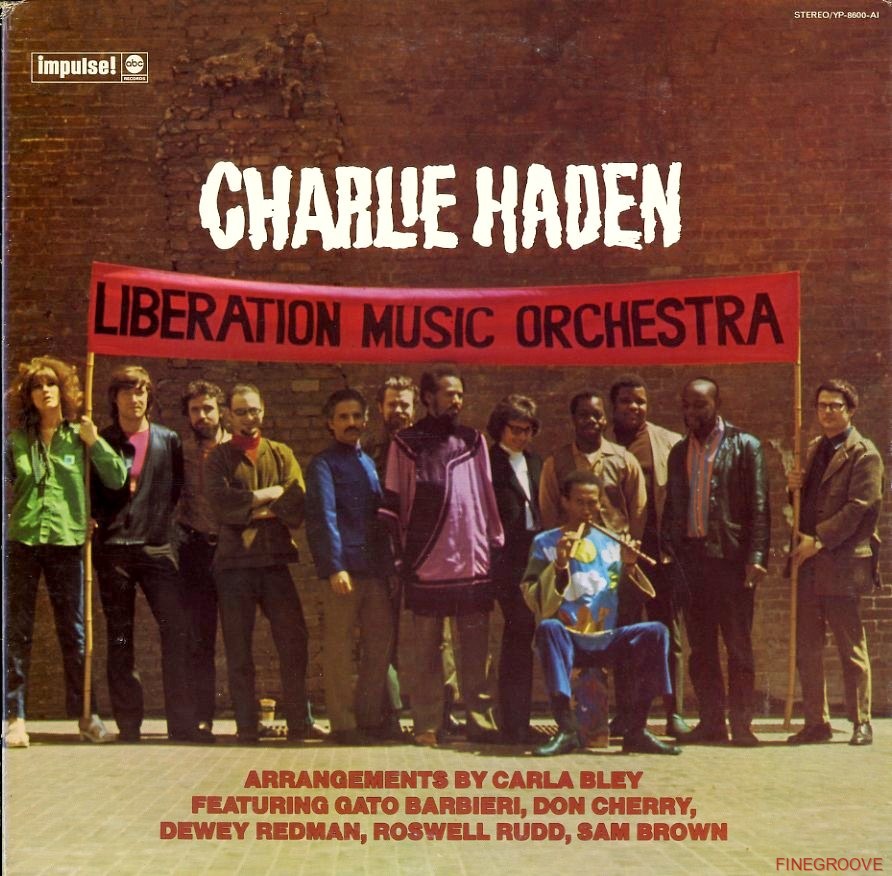

Haden produced the album with his wife Ruth Cameron, who co-produced most of his later work. You get a muted sense of Haden’s gifts for album concepts and socially-consciousness expression. There was a bracing, highly political side to Haden, most evident in the recordings he made periodically with his Liberation Music Orchestra with pianist-arranger-composer Carla Bley.

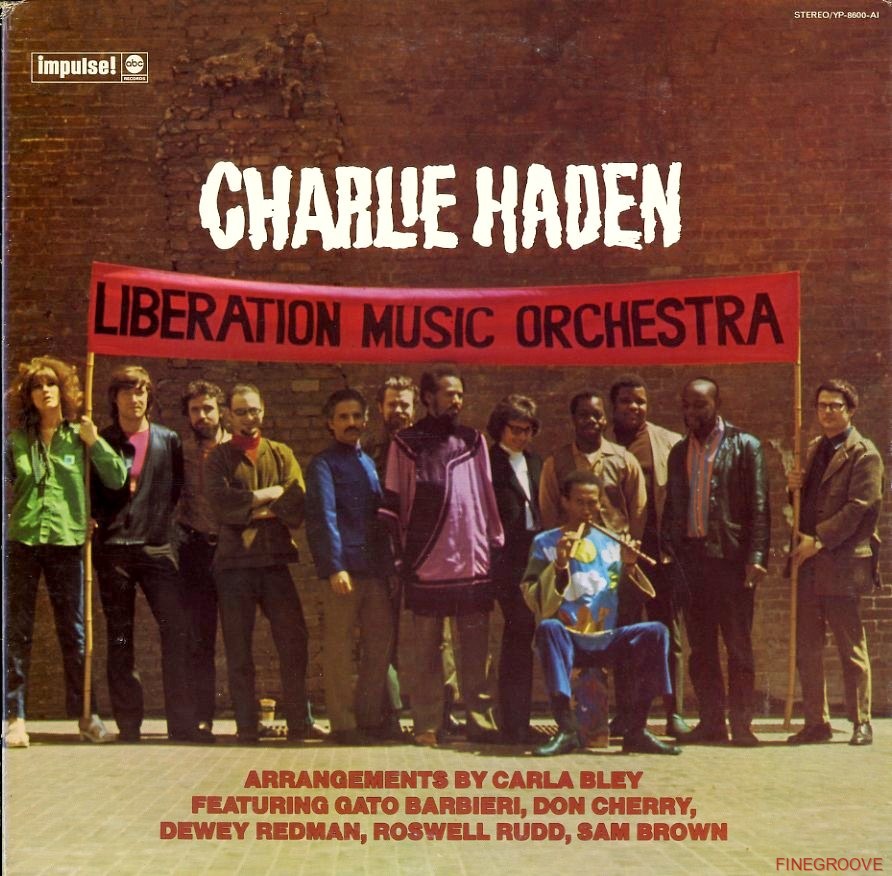

The first album, Liberation Music Orchestra from 1969, lends pointed purpose to the maelstrom of musical creativity, and social and political unrest that remarkable decade produced.

The first Liberation Music Orchestra album in 1969 set a standard for political jazz in a pan-cultural cast. Courtesy public-embarrassment-blues.blogspot.com

The Liberation Music Orchestra’s last recording, Not in Our Name, recorded in the summer of 2004, is a protest against the Iraq war, among other travesties of justice. The album also introduced many in the music world to the brilliant young Puerto Rican alto saxophonist Miguel Zenon, who may have no peer today on his instrument.

Not in Our Name superbly blends originals and folk-derived pieces by Bley, and various Americana: a sardonically harmonized “America the Beautiful,” part of a medley including a majestically soaring, trumpet-borne, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” and a quote from Haden’s old bandleader Ornette Coleman’s powerfully searching tone poem Skies of America. There’s also “Amazing Grace,” and “Goin’ Home” (the folk song used in Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony).

The album closes with their interpretation of Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings. The original material may not match that of the first Liberation Music Orchestra album, one of the great recordings of the modern jazz era, and perhaps this Adagio inevitably, with 12 musicians, couldn’t quite equal the luminous, searing orchestral beauty of Barber’s masterpiece, as scored for strings.

But few artistic statements in recent memory have shown a surer artistic and critical grip on the America of the present, without forsaking, trivializing or glibly diminishing it.

“People sometimes ask, does it make any difference to make a recording like this?” Haden and Bley wrote in their liner notes to Not in Our Name. “What is important is that we choose to express our concerns, when the circumstances warranted and our natural mode of expression is music.”

Haden knew that music has the vibrational power to move people unlike any other art form. He used that power wisely. He toured worldwide until his body began to break down.

Perhaps one of the first documented clues to this tireless creative musician’s deteriorating condition arose in an interview he did for Jazz Times in May 2011. Writer Don Heckman wrote:

“At the moment, seated in an Italian restaurant near his home in northwest suburb of Los Angeles, it’s a coffee he’s drinking that’s bothering him. He’s been coughing since he took the first sip. ‘Coffee!’ He mutters. ‘I keep drinking it, and I keep coughing,’ And then in his typically whimsical fashion, he laughs at the inadvertent pun.”

Respiratory problems are among the symptoms of post-polio syndrome. Heckman aptly characterizes Haden as a Renaissance man, and the interview ends with the journalist asking Haden if he thinks Renaissance men are born or made.

“Well, my parents were like that, too, and I’ve always, from the beginning, wanted to play different music from different parts of the world,” Haden replied. “And then, as I was exposed to the problems of society as I was growing up — racism, Vietnam — that affected me, too. But I think the simple answer is this: who you are and what you do comes from what’s inside you.”

A humble man of vision and ambition, who knew who he was, and what he became, and how to share that with world. In his speech given when he received a Lifetime Achievement Grammy award, you sense vulnerability in his crumbling stature and unsteady voice. Yet he always seem to know where he was going with or without anyone else.

His career had a magnificent sense of purpose, perhaps no more overtly is when he formed the Liberation Music Orchestra, one of the most powerful and eloquent ensembles ever dedicated to the idea of freedom. His eloquent solo on “Song for Che,” from the first Liberation Music Orchestra album from 1969, will burn through the ages as surely as the memory of Che Guevera, the man it commemorated.

Haden’s “Song for Che” preformed with Ornette Coleman: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fmoj_vdk_5U

I saw him play twice in Madison, once years ago with Keith Jarrett’s American Quartet with Dewey Redman and Paul Motian, a concert of lyrical and acerbic urgency. The second time was with his Quartet West, a project which explored his noirish, romantic side. The great Joe Lovano was to be special guest but needed to cancel, so an old West Coast compadre, Gary Foster, flew in for the gig.

Foster’s a fine post-bop/post-cool school player, but the concert didn’t fully persuade without Lovano, who can do romantic on tenor sax as well as anybody (see Lovano’s Celebrating Sinatra album). Some fans longed to hear a fiery Liberation Music Orchestra-type concert, but it’s good to remember that Charlie was also a romantic, which was part of his LMO idealism, but also his natural lyricism. And jazz concerts by definition always risk not fully working because they’re all partly improvised.

Regardless, Haden played magisterially, in the center of the stage, behind see-through studio-type acoustic baffles, always supremely attuned to his songful tone quality.

Courtesy charliehadenmusic.com

At his strongest, Haden sounds like a man carving his bass notes into an ancient oak tree.

Now people are commemorating him, singing songs for him, as he was once able to do with his family’s country music repertoire. The Haden Family was a popular Midwestern radio act when he was a boy and known as “Cowboy Charlie,” on the verge of being a star singer. Polio struck, robbing his singing voice.

He switched to bass and became interested in jazz after hearing Charlie Parker perform with Jazz at the Philharmonic. He headed to Los Angeles to study music and began performing with such local musicians as pianist Hampton Hawes and saxophonist Art Pepper before meeting iconoclastic saxophonist Ornette Coleman.

Charlie Haden on bass in the early 1960s, with Don Cherry on pocket trumpet, Ornette Coleman on plastic alto saxophone and Ed Blackwell on drums. Courtesy dailykos.com.

“Ramblin'” by Ornette Coleman with Charlie Haden: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kqwdRBWvPs0

Almost a lifetime later, Haden’s soft tenor voice gives a stunning rendition of “Wayfaring Traveler” on his Quartet West album The Art of the Song from 1999. You hear a man who’s willing or compelled to wander and yet, as he did as bassist in the “free” jazz of Coleman’s pioneering quartet, he always seemed to know where he was headed. That was a secret of his success as an intrepid improviser. “Wayfaring Traveler” is actually a spiritual.

Haden founded the jazz studies program at the California Institute of the Arts in 1982, and emphasized the spirituality of improvisation. So he was always on his way home, at least in spirit. He died in Los Angeles, with his musical family beside him, says ECM label publicist Tina Pelikan, who announced his death.

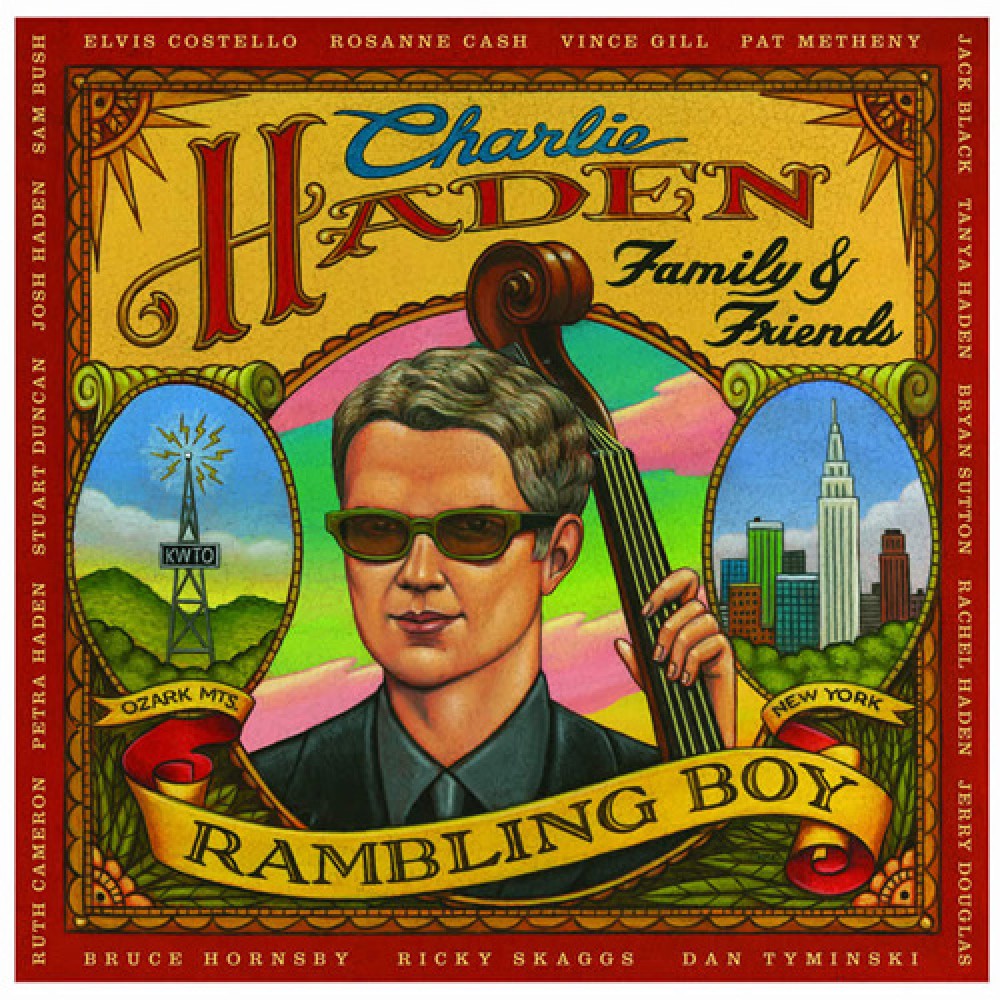

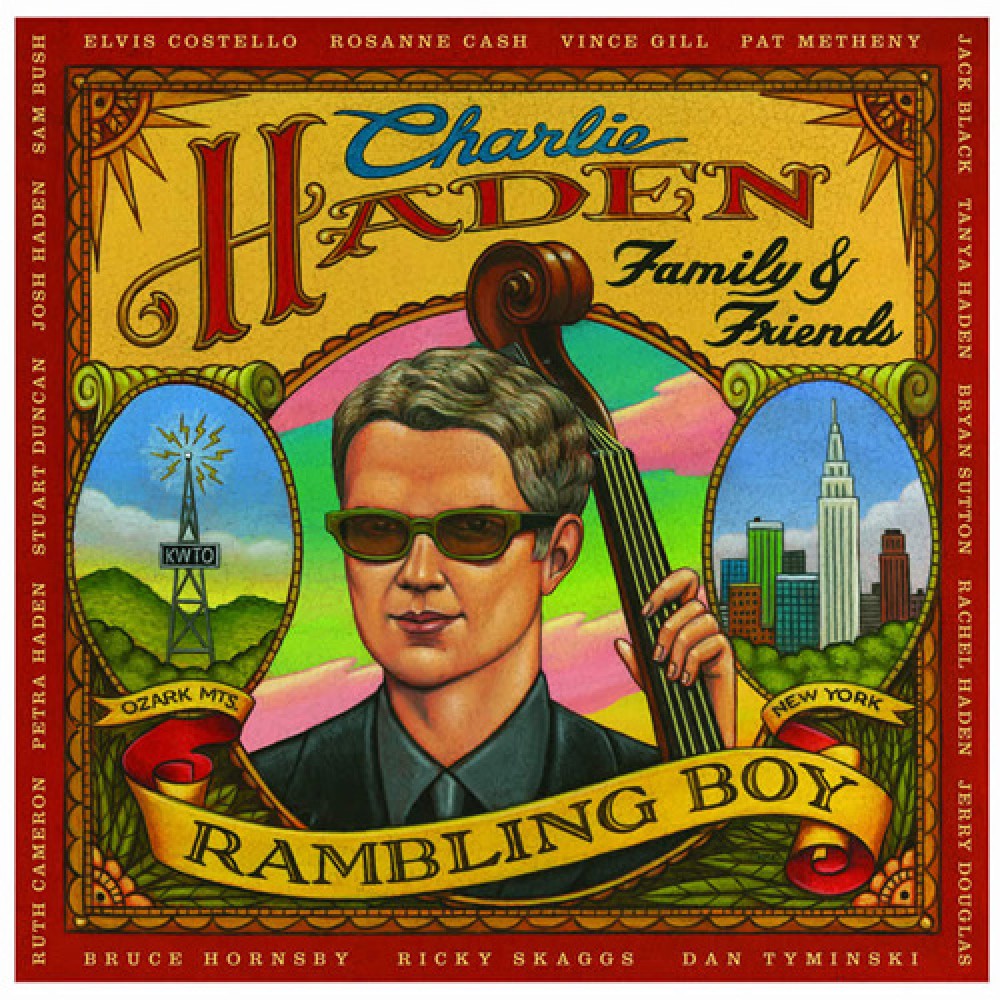

Rambling Boy from 2008 is a gorgeous, moving and fascinating document and, in effect, a modern-day Haden Family album, with a gaggle of guest roots-music stars – a measure of the respect he’s earned across musical vernaculars and

in the jazz, country, folk, classical and world music realms. This is Charlie the global rambler finally coming full circle.

You hear Haden, wife Ruth Cameron, the piquant harmonies of their triplet daughters Rachel, Petra and Tanya, their son Josh and son-in-law, actor Jack Black — and Elvis Costello, Rosanne Cash, Vince Gill, Jerry Douglas, Dan Tyminski, Bruce Hornsby, Ricky Skaggs, Pat Metheny and others.

“My roots have never left me … because the very first memory I have is my mom singing and me singing with her,” Haden said in a 2009 interview. The CD includes Haden’s first recorded performance – an excerpt from a 1939 Haden Family radio show on which 22-month-old Cowboy Charlie yodels on a gospel tune, already with an innate feel for phrasing.

A vintage photo of the original Haden Family with “Cowboy” Charlie Haden in center, (wearing a vest). Courtesy newswbt.com

Amid the bigger names, Haden’s unheralded son Josh offers “Spiritual,” a stunningly confessional supplication to Jesus: “I don’t want to die alone.”

The last song on Rambling Boy is Haden himself singing “Oh Shenandoah,” like a prodigal ghost. He returned, longing to hear Shenandoah, again, that rolling river.

The Shenandoah will always sing, for Charlie Haden. Night, and the city, singing itself to sleep, will as well.

____________________

Editorial assistance by Harvey Taylor, Michael Goldberg, Howard Landsman, Gary Alderman and Steve Braunginn.

A selected Charlie Haden discography:

With Ornette Coleman: The Shape of Jazz to Come, Change of the Century, This Is Our Music, Atlantic, early 1960s recordings; Beauty Is A Rare Thing (box-set reissue) Rhino/Atlantic, 1993; Crisis, Impulse! 1972, The Complete Science Fiction Sessions, with Bobby Bradford, Jim Hall, Cedar Walton, Ashla Puthli, and others, recorded 1971, Columbia, 2000.

With The Keith Jarrett Quartet: Death and the Flower, Impulse! 1977; Survivor’s Suite, ECM 1977

With Rickie Lee Jones: Pop-Pop, Geffen, 1991

With Abbey Lincoln: You Gotta Pay the Band, Verve, 1991

With Joe Lovano: Universal Language Blue Note 1992

With John McLaughlin: My Goal’s Beyond, Douglas 1970

With Helen Merrill: You and the Night and the Music, 1998

With Pat Metheny: Song X, with Ornette Coleman, Jack DeJohnette, Geffen 1986

With Old and New Dreams: Old and New Dreams, with Don Cherry, Dewey Redman and Ed Blackwell, Black Saint (Italian) 1977; and Old and New Dreams ECM 1979 (re-issued in 2005 as Lonely Woman on Universal.)

___

Charlie Haden:

Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra, with Carla Bley, Don Cherry, Dewey Redman, Gato Barbieri and others. Impulse! 1969

Closeness (Duets), with Keith Jarrett, Ornette Coleman, Alice Coltrane, Paul Motian, recorded 1976. Jazz Heritage

Time Remembers One Time Once, duets with (pianist) Denny Zeitlin, ECM 1979

Silence, with Chet Baker, Enrico Pieranunzi, Billy Higgins, Soul Note (Italian) 1987 (six months before Baker’s death)

Etudes with Paul Motian, featuring pianist Geri Allen, Soul Note (Italian) 1988

Dream Keeper, Liberation Music Orchestra, with Joe Lovano, Branford Marsalis, Ken McIntyre, Tom Harrell and others, Blue Note, 1991

Haunted Heart, Charlie Haden Quartet West, Verve 1992

Night and the City, duets with pianist Kenny Barron, Verve, 1994

Steal Away: Spirituals, Hymns and Folk Songs, duets with pianist Hank Jones, 1995

Beyond the Missouri Sky (Short Stories) with Pat Metheny, Verve, 1996

The Art of the Song, Quartet West, with Shirley Horn, Verve 1999

Not in Our Name, Liberation Music Orchestra, with Carla Bley, Miguel Zenon, Curtis Fowlkes and others, Verve 2005

Rambling Boy, Charlie Haden Family & Friends, with Elvis Costello, Rosanne Cash, Jerry Douglas, Dan Tyminski, Bruce Hornsby, Ricky Skaggs, etc. Decca 2008

Jasmine, duets with Keith Jarrett ECM 2010

Sophisticated Ladies, Quartet West, with Cassandra Wilson, Diana Krall, Norah Jones, Renée Fleming and others, Decca Emarcy (import) 2010

Come Sunday, duets with Hank Jones (Jones’ last recording) Verve 2012

Last Dance, duets with Keith Jarrett, ECM 2014

___

“Rambling Boy” CD cover courtesy mike-oldfield.com

Like this:

Like Loading...

Unfortunately, lovely as she is, Chloe sometimes is too busy nosing into dusty corners to always put her absolute best face on for the camera, as was the case in these two early close-ups of her — after she had just spent some time rooting around in the basement. She came up with dust goobers on her left ear and forehead. She’s very exploratory and somewhat fearless, so I’ll have to keep my eye on her, Note to self: Assign her personal secret service agents.

Unfortunately, lovely as she is, Chloe sometimes is too busy nosing into dusty corners to always put her absolute best face on for the camera, as was the case in these two early close-ups of her — after she had just spent some time rooting around in the basement. She came up with dust goobers on her left ear and forehead. She’s very exploratory and somewhat fearless, so I’ll have to keep my eye on her, Note to self: Assign her personal secret service agents.  Chloe’s a serious chow hound, er, cat. I’m trying to resist giving her table scraps but with a pretty puss like hers…it’s just a matter of time. Here she was, behind my back so who knows how much she wolfed down, er, ate? When she gets her squishy canned Fancy Feast she does tend to wolf it. “You’re a cat, Chloe. Don’t wolf you food,” I say.

Chloe’s a serious chow hound, er, cat. I’m trying to resist giving her table scraps but with a pretty puss like hers…it’s just a matter of time. Here she was, behind my back so who knows how much she wolfed down, er, ate? When she gets her squishy canned Fancy Feast she does tend to wolf it. “You’re a cat, Chloe. Don’t wolf you food,” I say.  Here she is, sizing up her subject (moi), deciding whether she’ll keep me. I offer a tentative petting hand for her pleasure…

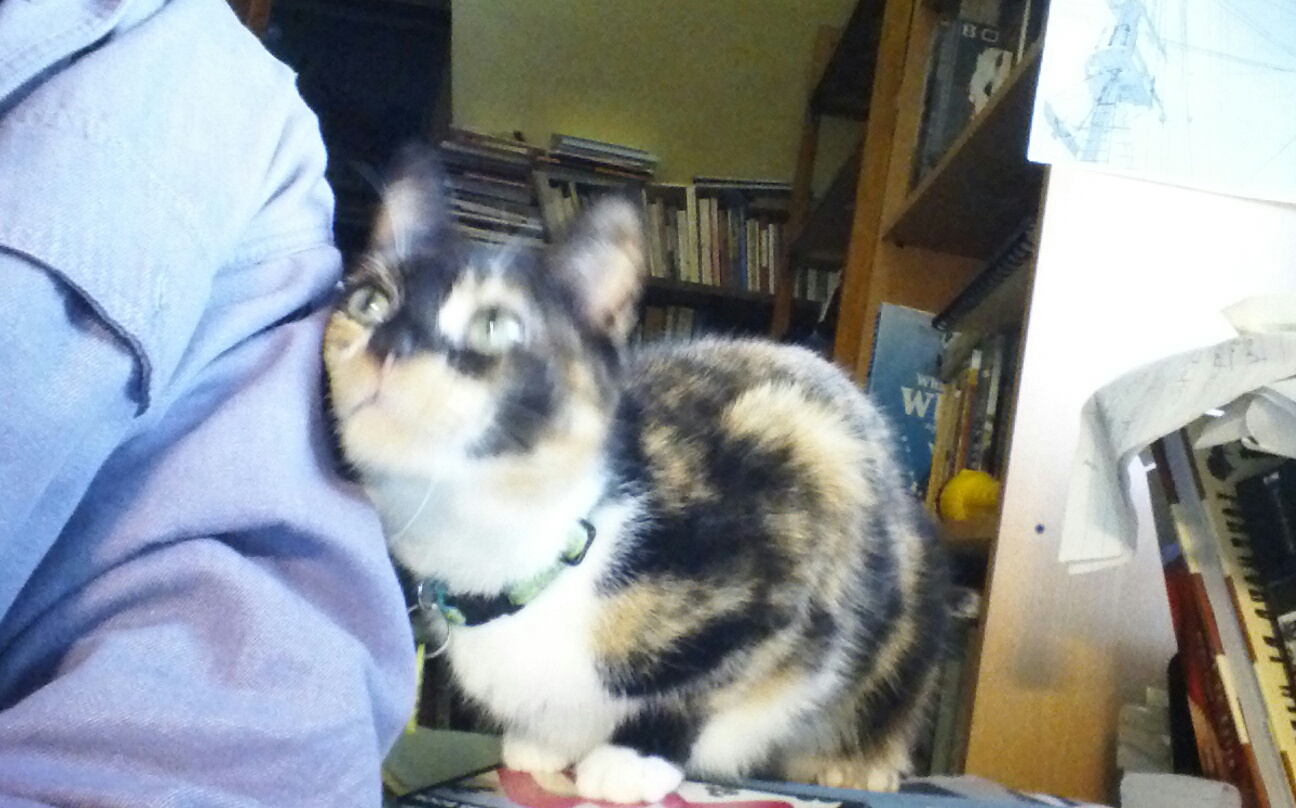

Here she is, sizing up her subject (moi), deciding whether she’ll keep me. I offer a tentative petting hand for her pleasure…  I start with fingers to the neck, a slight nuzzling stroke and slowly work my way to the relative royal intimacy of a full palm massaging of her upper body. “Hmmmm, yes, I believe he’ll do, for now…But what sort of a name is Kevernacular?”

I start with fingers to the neck, a slight nuzzling stroke and slowly work my way to the relative royal intimacy of a full palm massaging of her upper body. “Hmmmm, yes, I believe he’ll do, for now…But what sort of a name is Kevernacular?”  Sunlight does wonders for Chloe’s queenly complexion…

Sunlight does wonders for Chloe’s queenly complexion…  …But she’s far more than just a porcelain-pretty kitty. Here she springs into action, pursuing a real (or imagined) bug by squeezing herself into the one-and-half-inch-wide space between the window screen and the window frame. Maggie would never have dreamed of trying a stunt like this. BTW The wood sculpture is “Chained Life Force” by Kevin Lynch (Kevernacular).

…But she’s far more than just a porcelain-pretty kitty. Here she springs into action, pursuing a real (or imagined) bug by squeezing herself into the one-and-half-inch-wide space between the window screen and the window frame. Maggie would never have dreamed of trying a stunt like this. BTW The wood sculpture is “Chained Life Force” by Kevin Lynch (Kevernacular). Queen Chloe really likes basking in the balcony sun, but the flora and fauna soon get her dreaming of the wilds of the jungle. Before long, she is prowling around, doing her best “caged panther” routine. At least she seems to strike terror in the heart of my concrete gargoyle!

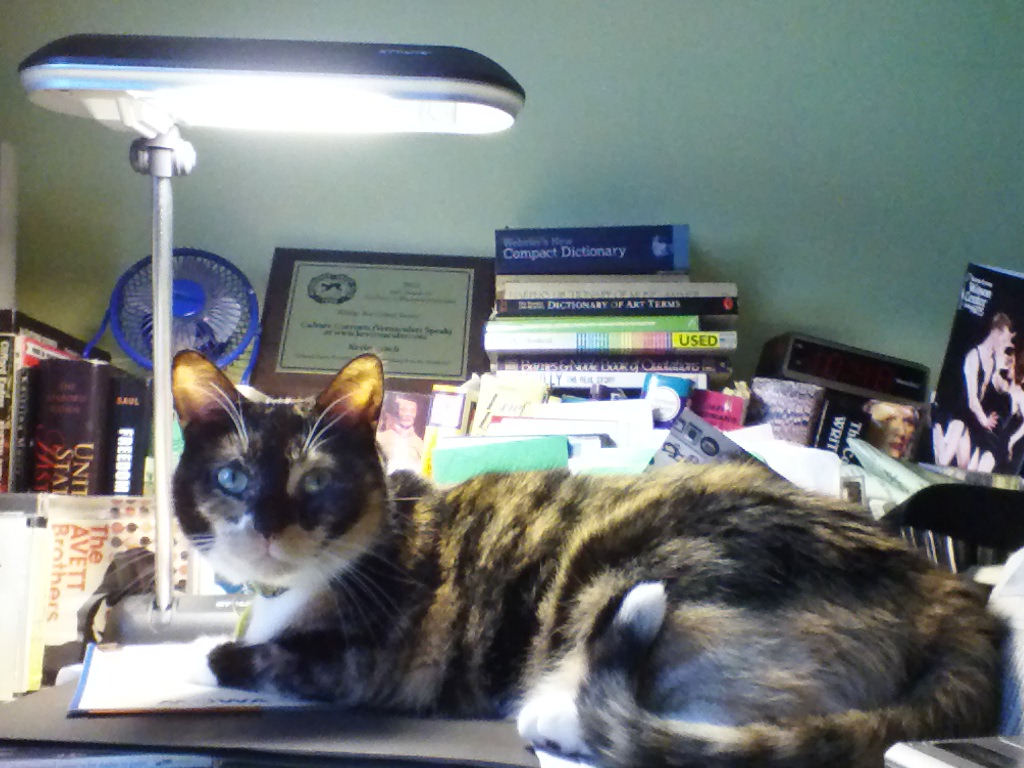

Queen Chloe really likes basking in the balcony sun, but the flora and fauna soon get her dreaming of the wilds of the jungle. Before long, she is prowling around, doing her best “caged panther” routine. At least she seems to strike terror in the heart of my concrete gargoyle!  Chloe decides to try out my office desk. She measures the space and the clutter…

Chloe decides to try out my office desk. She measures the space and the clutter…  …and decides it suits her just fine, to my great relief.

…and decides it suits her just fine, to my great relief.  …before long she realizes in that position she is too subject to my inadvertent elbowing, not to mention the ongoing clutter of papers, books, CDs and pens… So she decides to relocate to my messy “inbox” above my desktop computer’s keyboard. Here she takes on a new and greatly valued role as my sharp-penned editor in, among other things, my quest to complete my novel about Melville. Soon I may need to fit her with reading glasses.

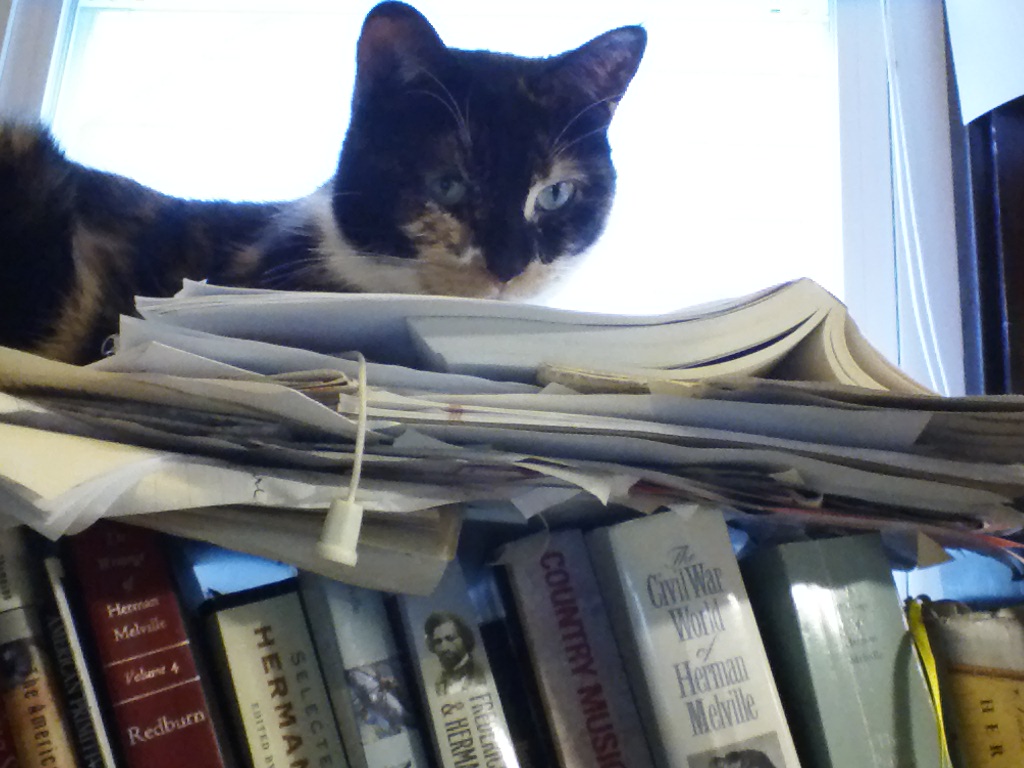

…before long she realizes in that position she is too subject to my inadvertent elbowing, not to mention the ongoing clutter of papers, books, CDs and pens… So she decides to relocate to my messy “inbox” above my desktop computer’s keyboard. Here she takes on a new and greatly valued role as my sharp-penned editor in, among other things, my quest to complete my novel about Melville. Soon I may need to fit her with reading glasses.  But any truly royal Kitty soon tires of the lonely pursuits of the the literary life.

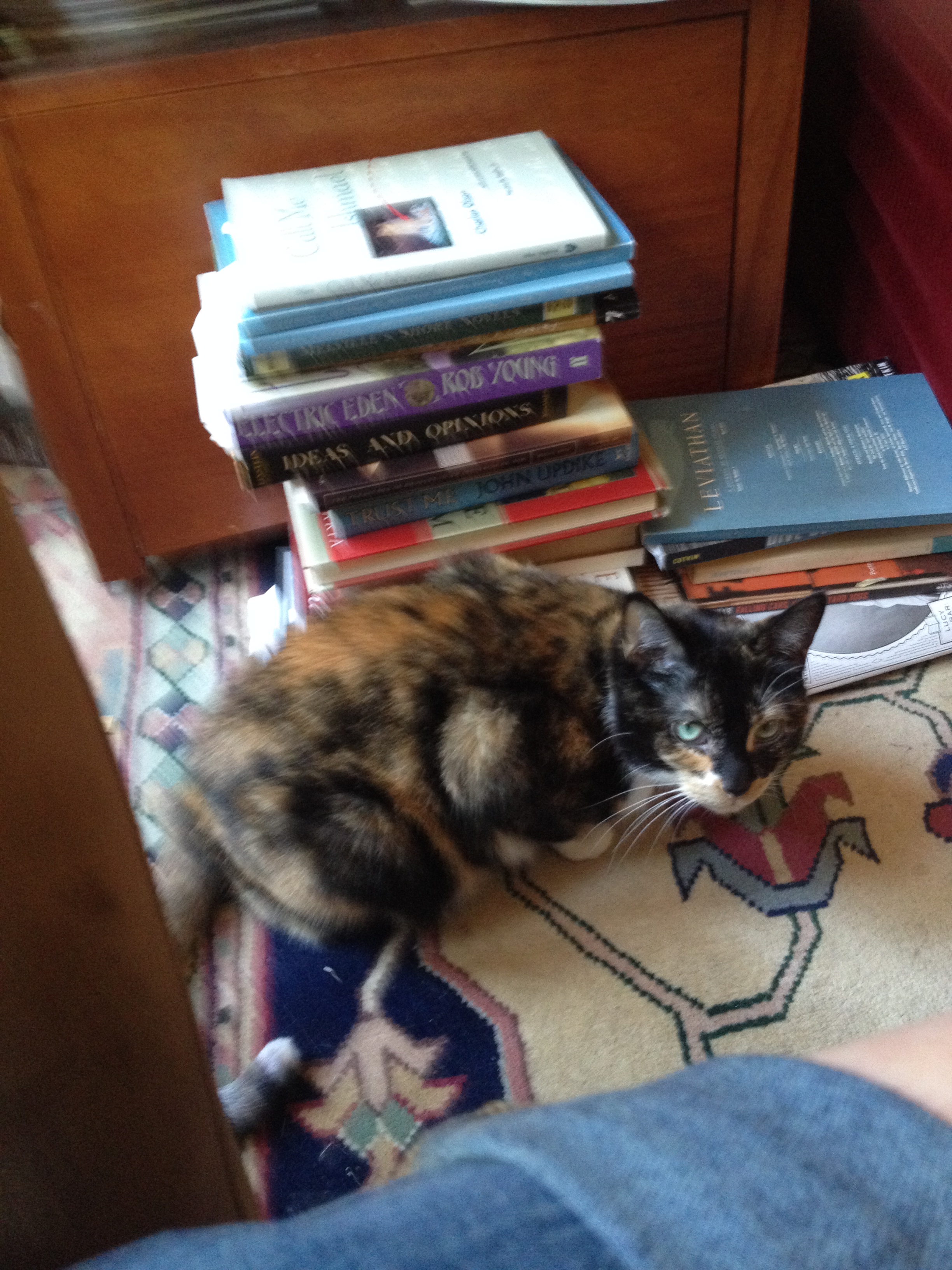

But any truly royal Kitty soon tires of the lonely pursuits of the the literary life.  I push my luck by suggesting some good reading material for her. “Ach, it’s just a bunch of ideas and opinions,” she sniffs. “Did that Einstein fellow have any good theories about perfecting the ultimate squishy cat food? Huh?” Photo by Ann Peterson

I push my luck by suggesting some good reading material for her. “Ach, it’s just a bunch of ideas and opinions,” she sniffs. “Did that Einstein fellow have any good theories about perfecting the ultimate squishy cat food? Huh?” Photo by Ann Peterson “I’d much rather you take me out to the old ballgame,” she persists. “You can have the beer but I’d gladly try the hot dogs and brats. I especially like biting into dogs and, then, not having to run.” Photo by Ann Peterson

“I’d much rather you take me out to the old ballgame,” she persists. “You can have the beer but I’d gladly try the hot dogs and brats. I especially like biting into dogs and, then, not having to run.” Photo by Ann Peterson  Then at the end of the day, another faux pas by yours truly: “Why has my bubble bath not been drawn?!!” the queen cries. “Off with his head!” (…I know the sleazy tabloid video cameras will be rolling for this, she thinks, [Sigh] ‘Tis a queen’s burden. I must keep the peasants and riff-raff entertained every blue moon, or they get surly and start grumbling about filthy streets and other weary rubbish…)

Then at the end of the day, another faux pas by yours truly: “Why has my bubble bath not been drawn?!!” the queen cries. “Off with his head!” (…I know the sleazy tabloid video cameras will be rolling for this, she thinks, [Sigh] ‘Tis a queen’s burden. I must keep the peasants and riff-raff entertained every blue moon, or they get surly and start grumbling about filthy streets and other weary rubbish…)  Well, it seemed like a trial under fire, a harrowing gauntlet, for me to gain the queen’s approval and trust, when suddenly she leapt up to the desk and…Fast friends!…so it seems.

Well, it seemed like a trial under fire, a harrowing gauntlet, for me to gain the queen’s approval and trust, when suddenly she leapt up to the desk and…Fast friends!…so it seems.  Yep, fast friends. Everything’s purrr-fectly hunky dory. I’m OK and she’s my queen.

Yep, fast friends. Everything’s purrr-fectly hunky dory. I’m OK and she’s my queen.

Sarah Day as Joan Didion. Photos by Zane Williams

Sarah Day as Joan Didion. Photos by Zane Williams