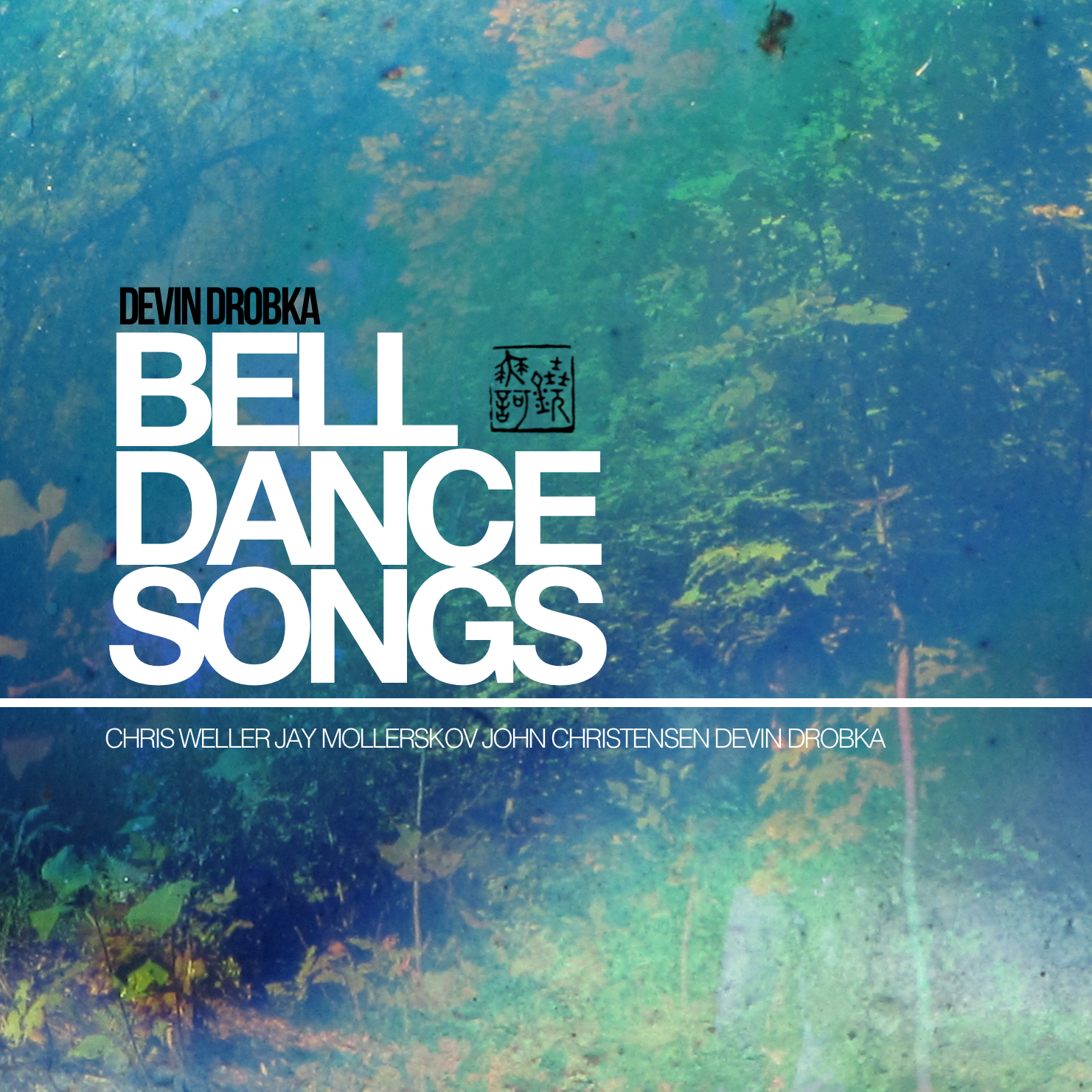

Devin Drobka — Bell Dance Songs. CD review

Devin Drobka evokes fellow composer-percussionist Paul Motian, one of his influences and heroes, like a kind of guiding light throughout this album. The CD-opening “Blues Town,” exploits the fraught relationship between a elegantly unfolding, mournful melody and a rhythmic pulse that pushes the melody like waves lapping against a rocky shore.

Bell Dance Songs brims with such melodic and rhythmic tensions, often evoking dance-like rhythms, as a bell’s ring might, resonating in circular fashion more than articulating step patterns or back beats. This creative activity is very characteristic of Motian, who always defied conventions of the rhythm-maker’s role.

Another eccentric but fecund jazz innovator, guitarist Bill Frisell, emerges as a contrasting inspiration to expand the sonic and conceptual palette on “It’s Been Days Since I’ve Heard from You.” This melody arrives at an even slower, a funereal pace, and Jay Mollerskov’s space-twang guitar creates a brief portrait, suggesting a lonely prospector with little hopes of discovering much more than the wind, and dust in his teeth. Bassist John Christensen and saxophonist Chris Weller plumb inconsolably sad notes. The idea of hearing from a friend or lover feels remote, another broken dream.

The pace picks up on “For Paul (Dia de)” when the drums again boost the melody to higher pitches. Saxophonist Weller and guitarist Mollerskov alternate in two-part solos, the former with Coltrane-esque courage, like the cry of a plunging eagle. Then the sax climbs a steep and precipitous sonic plane. The latter plays a welter of angularity, increasingly atonal. Amid this, drummer Drobka unfurls a fusillade of drum rolls at different dynamic angles, in this explicit Motian tribute.

Drummer-composer Devin Drobka Courtesy wmse.org.

Drummer-composer Devin Drobka Courtesy wmse.org.

For its challenges, Bell Dance Songs allows breathing spaces, like “Restless Dogs” which cuts away the bricolage while maintaining the eccentric manner and articulation.

Although a pianoless quartet, Drobka’s group sometimes recalls pianist Keith Jarrett’s 1970s American quartet with Motian and saxophonist Dewey Redman, with its roiling rhythms and forlorn, piquant melodies. But on “Bring Out Your Dead,” free of pianistic harmonic underpinnings, the guitar and sax stoke a fire of sizzling expressionistic interplay, while forging their own entangled melodic ways. The composer confirms that this slightly madcap energy was inspired by absurdist British comedy troupe Monty Python, from a skit titled “Bring out Your Dead.”

This gives you a little idea of the the evocative power of these songs. In concert recently at The Jazz Estate, Drobka related fairly extensive and vivid anecdotes that inspired each composition. I asked him to elaborate on one at length, which involved a dream, a tune called “Ishan”:

“In the dream he was lying in his own bed but in a completely different room. A door opening awoke him and a shirtless man entered with long curly hair and a tattoo across his side, a highly stylized Audubon’s (rain) barrel body but with the head of a very geometric owl. I get up from my bed and asked who he was.

“Do not worry, my name is Ishan,” he replied. “I lied back in bed and he proceeded to sit at a desk in the corner. I looked away and when I turned back and look at him his hair is extremely short. He stands up and proceeds to walk out of the room. I follow and enter a gigantic rectangular room. Something like 150 by 45 feet, and all the walls were glass with dense foliage pressing against the windows. In the center’s great hall stood a long wooden table, about 90 feet, covered in books. The table is right underneath a skylight that was the same length as the table. Inside a tremendous storm arose. I could feel the wind and rain as if they engulfed the room.

Following Ishan closer to the table, one book stood out. “It was the largest book on the table and its pages were rapidly flapping because of the win. As I walked up I put my hand out to stop the pages and as soon as I did that, I awoke.”

It’s a not-untypical dream, a little peculiar but not too bizarre and with reasonably interpretable symbolism. Ishan seems to signify some kind of literary/environmentalist guru or shaman, and it suggests to me the desire for extraordinary guidance about our environmental crisis. The owl traditionally symbolizes wisdom, among societies close to the earth.

I’m happy Drobka still feels a real book is the source of such knowledge rather any of today’s more facile electronic media. So he finds a large book that might be a Bible, but more likely something environmentally substantial, like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring or Thoreau’s Walden, or a book of Wendell Berry poems, even if those are shorter works. Or an authoritative anthology of environmental writing such as American Earth edited by writer-activist Bill McKibben. Or the latest scientific research on global warming.

Or something was more pagan or zen, given the shaman implications. And its reasonable to ultimately see the mystery shaman as Motian, the defier of rhythmic convention, but the true conjurer of creative possibility.

Ultimately what counts is how well “Ishan” works as music, clearly with evocative inspiration, and this piece, like most of them, conveys a storytelling quality that gets the imagination asking questions of itself.

These are superb ambitions and accomplishments for composition and improvisation, and often well-realized on this record. It’s also a brilliantly indirect way of conveying a holistic environmental ethos. The album cover photo beautifully depicts a vulnerable rain forest. And bell dances suggest a ritual type of act, generating vibrations connecting with the mystical “music of the spheres.” Who can’t feel at least sympathy for such a world view? Drobka might suggest more than sympathy is needed for the planet’s survival.

My only caveat for this album is that, without Drobka’s diverting and guide-posting anecdotes (good material for missing liner notes), a fairly swinging or funky tune would have complemented and eased the insistently heady interplay. The band played an infectious funk tune at the Estate. Despite their tropes, swing and funk can still generate avenues of fresh ingenuity.

Bell Dance Songs conveys a tersely ardent energy that asks the listener to meet it half way. If you enjoy conceptual open air shifting under your feet, where structures turn into startling and lyrically probing shapes, if you like music to chew on, this is your record.

Bell Dance Songs is currently available online for only $5 at http://cargocollective.com/devindrobka

The Devin Drobka Quartet will perform at The Bay View Jazz Festival at 9 p.m. Friday June 6, at Studio Lounge, 2246 S. Kinnickinnick Ave.

___________

Album cover photo courtesy bsidegraphics.com

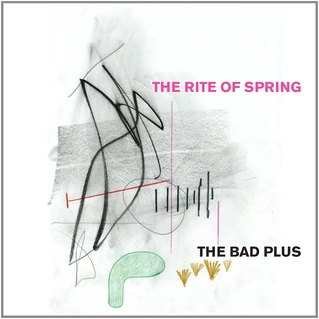

The Bad Plus: The Rite of Spring (Masterworks)

The Bad Plus: The Rite of Spring (Masterworks) The Bad Plus perform “The Rite of Spring” live in Boston. From left, pianist Ethan Iverson, bassist Reid Anderson, drummer Dave King. Courtesy bostonglobe.com.

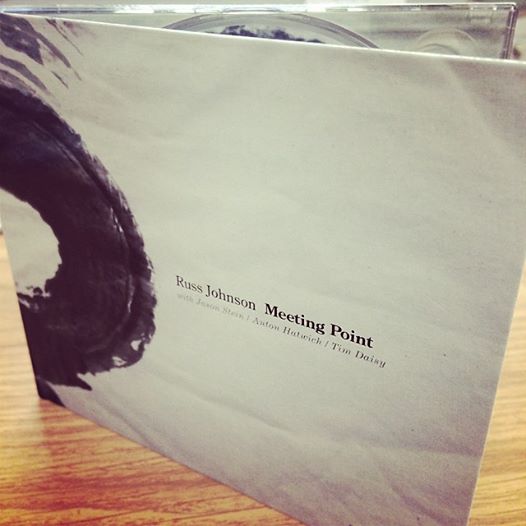

The Bad Plus perform “The Rite of Spring” live in Boston. From left, pianist Ethan Iverson, bassist Reid Anderson, drummer Dave King. Courtesy bostonglobe.com. Russ Johnson — Meeting Point (Relay Recordings) CD review

Russ Johnson — Meeting Point (Relay Recordings) CD review  Johnson has done as much as any recent musician to keep Dolphy’s legacy alive, having performed the music from Dolphy’s classic Out to Lunch album at a special event honoring Dolphy, which included the unveiling of a bronze statue of the great jazz wind player at LeMoyne College in 2010 (Most of Johnson’s Dolphy interpretations are readily available on YouTube).

Johnson has done as much as any recent musician to keep Dolphy’s legacy alive, having performed the music from Dolphy’s classic Out to Lunch album at a special event honoring Dolphy, which included the unveiling of a bronze statue of the great jazz wind player at LeMoyne College in 2010 (Most of Johnson’s Dolphy interpretations are readily available on YouTube).

Kevernacular (Kevin Lynch) received a “gold award” plaque for the Culture Currents blog Friday at the Milwaukee Press Club awards dinner. To quote Sen. Elizabeth Warren, “I never dreamed I would be a blond.” Photo by Ann K. Peterson

Kevernacular (Kevin Lynch) received a “gold award” plaque for the Culture Currents blog Friday at the Milwaukee Press Club awards dinner. To quote Sen. Elizabeth Warren, “I never dreamed I would be a blond.” Photo by Ann K. Peterson

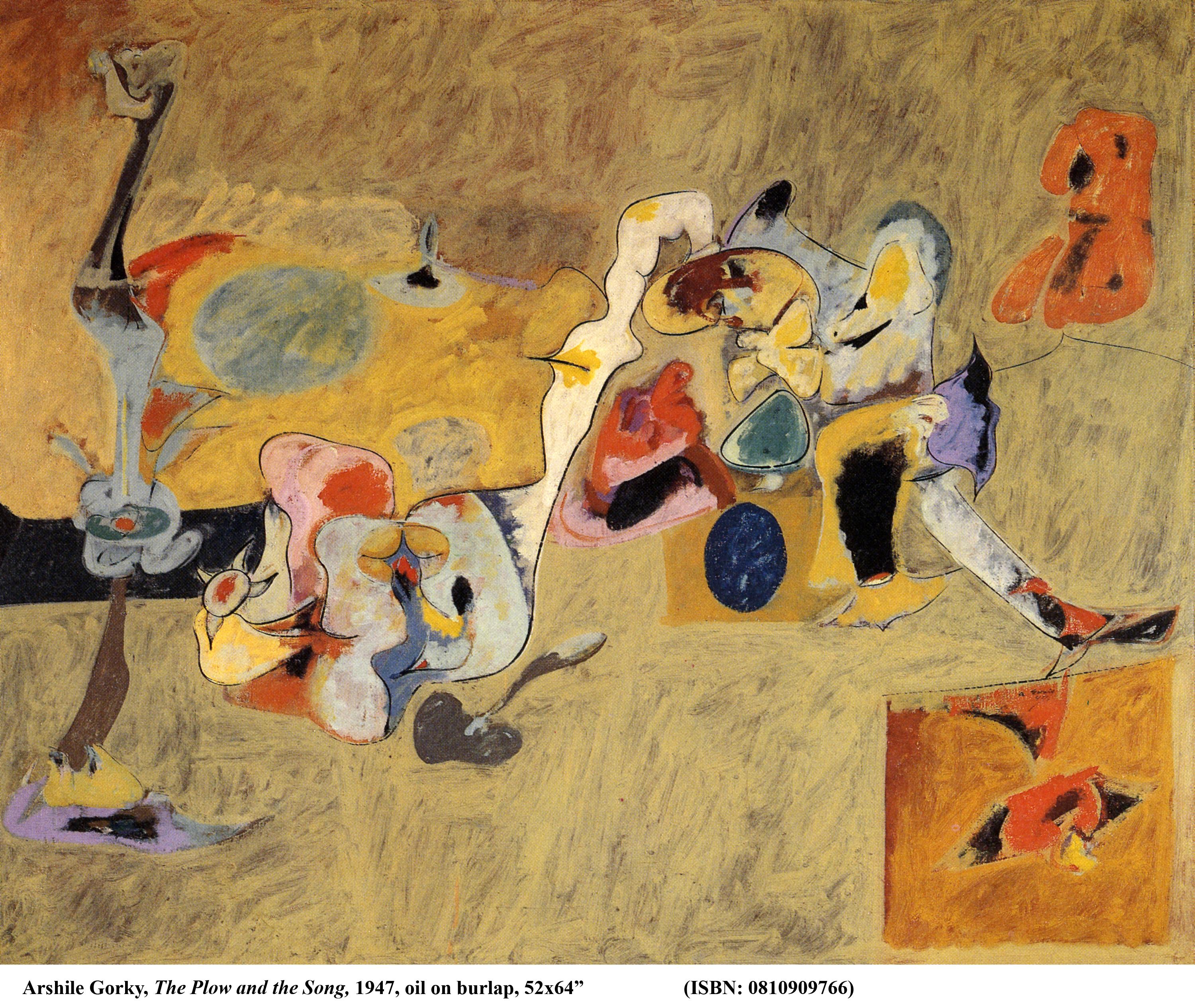

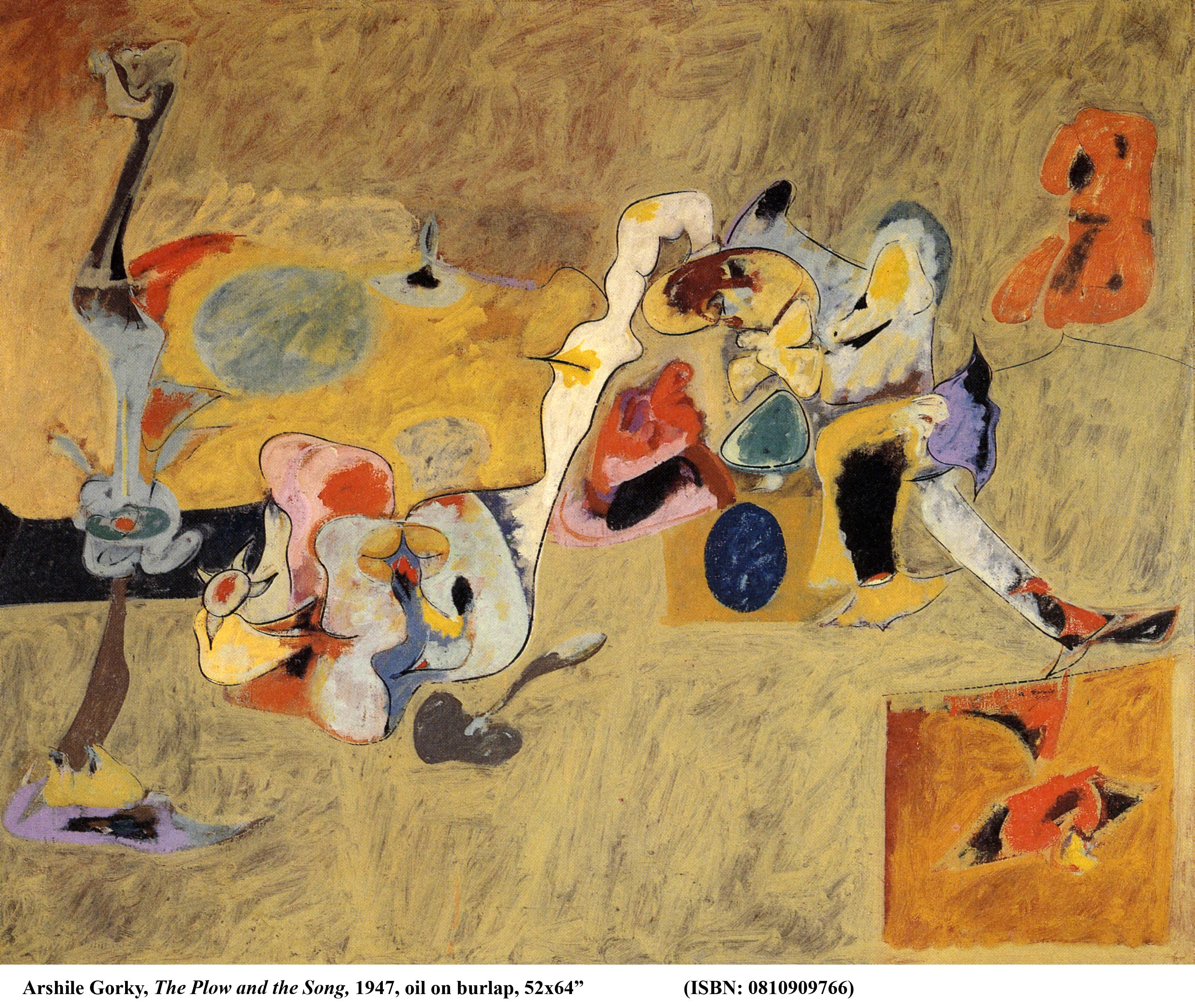

Arshile Gorky “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” oil on canvas 1944. These two paintings are superb examples of Gorky’s great skill at hanging a composition along the formal undergrid of The Golden Mean. The proportional ideal allowed Gorky guidance as he explored the boundaries of surrealism and abstraction. Much of this best work derives from his intensely close observations of nature. In one famous instance, Gorky laid face-down in a garden, opened his eyes and took in the visual sensation of this extreme perspective. In this manner, one can begin to understand the relationship between acquired impressions and an artist’s abstractions.

Arshile Gorky “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” oil on canvas 1944. These two paintings are superb examples of Gorky’s great skill at hanging a composition along the formal undergrid of The Golden Mean. The proportional ideal allowed Gorky guidance as he explored the boundaries of surrealism and abstraction. Much of this best work derives from his intensely close observations of nature. In one famous instance, Gorky laid face-down in a garden, opened his eyes and took in the visual sensation of this extreme perspective. In this manner, one can begin to understand the relationship between acquired impressions and an artist’s abstractions.

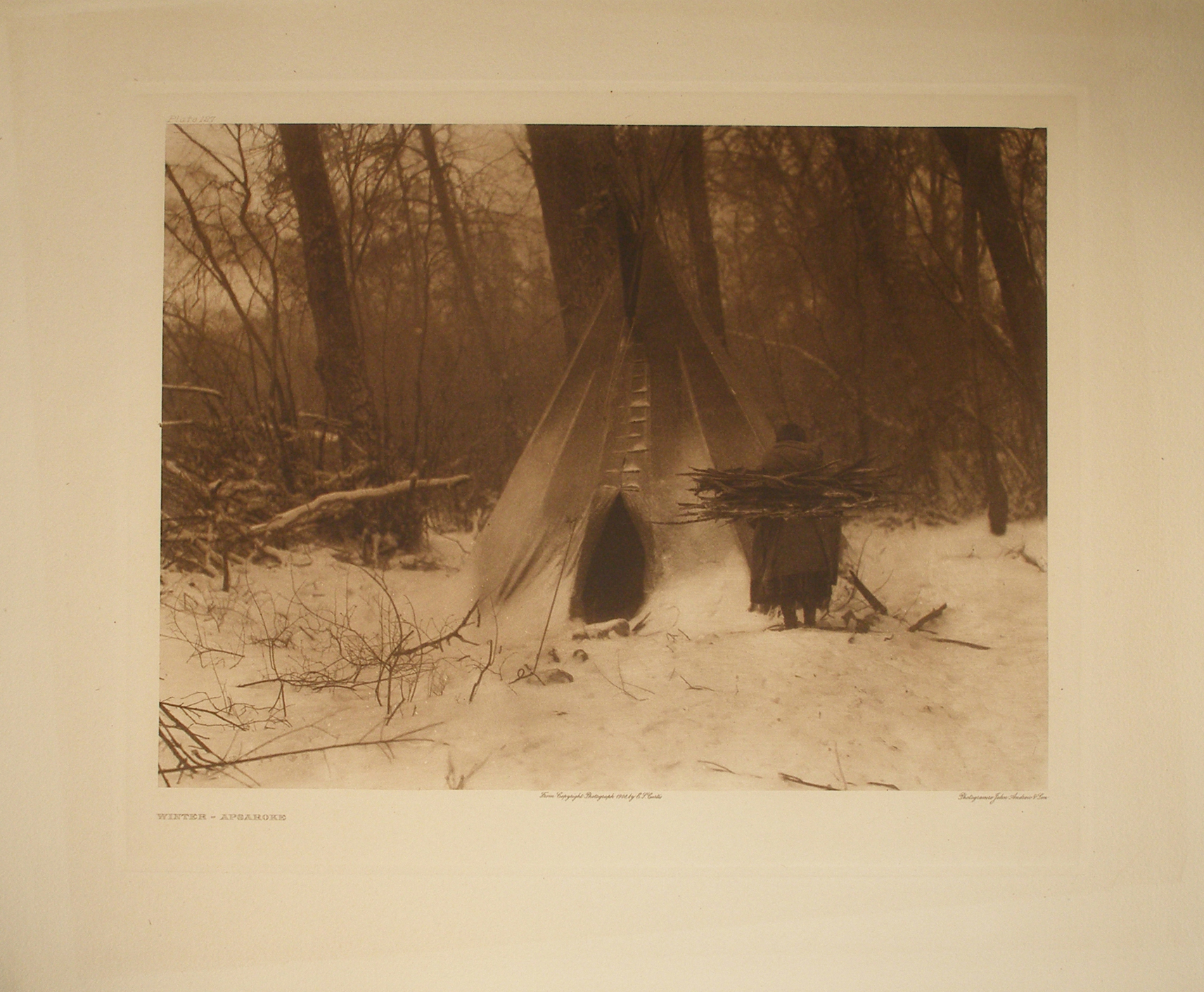

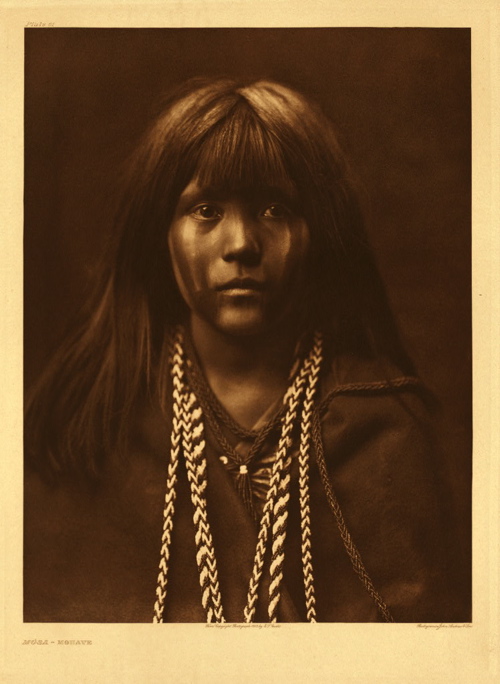

Edward S. Curtis. “Mosa – Mojave” 1903. This is the extraordinary portrait by Curtis that so enchanted millionaire J.P. Morgan that he became a crucial patron of The photographer’s Curtis’ pioneering anthropological effort to document the death of Native American culture and life in its original forms.

Edward S. Curtis. “Mosa – Mojave” 1903. This is the extraordinary portrait by Curtis that so enchanted millionaire J.P. Morgan that he became a crucial patron of The photographer’s Curtis’ pioneering anthropological effort to document the death of Native American culture and life in its original forms.  Rembrandt van Rijn “Self Portrait,” oil on canvas 1661, This late-life masterpiece was on display last year at the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Rembrandt van Rijn “Self Portrait,” oil on canvas 1661, This late-life masterpiece was on display last year at the Milwaukee Art Museum. Rita Cox with one of her “underground railroad” quilts, from the book “Hidden in Plain View.” Photo by Richard Allen.

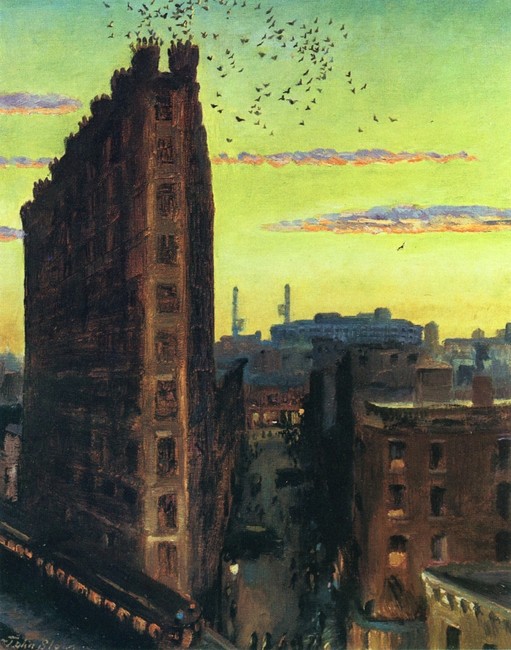

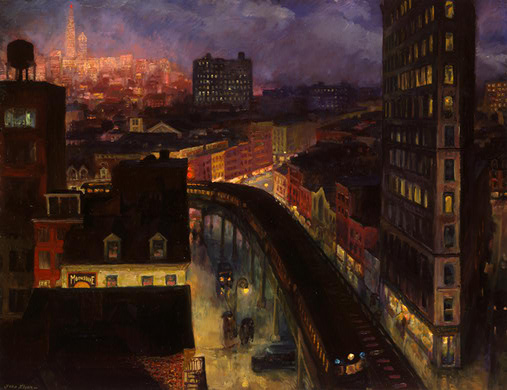

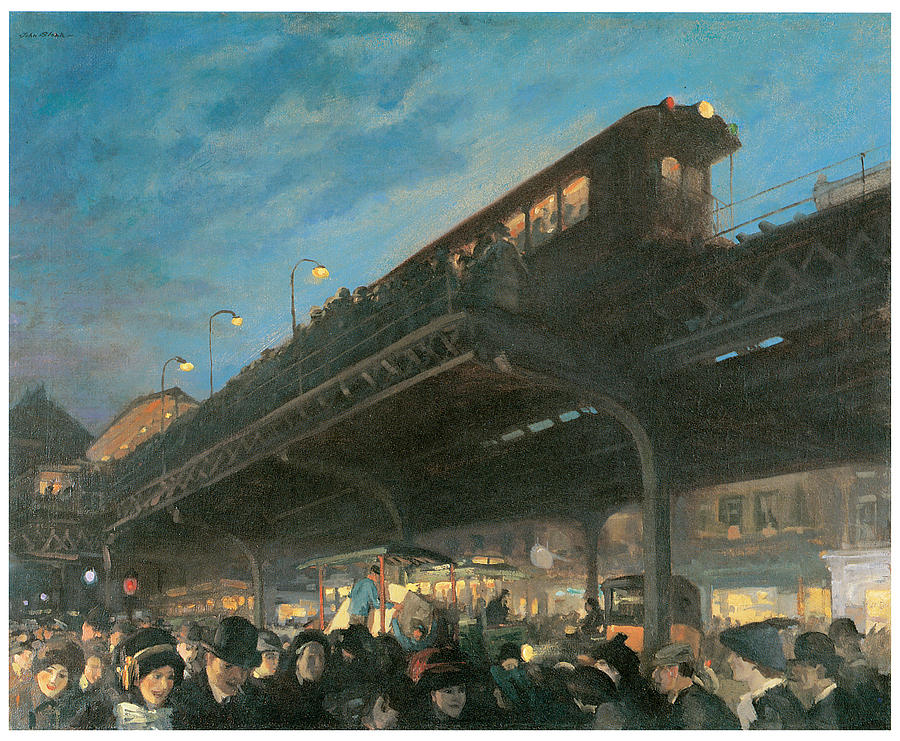

Rita Cox with one of her “underground railroad” quilts, from the book “Hidden in Plain View.” Photo by Richard Allen. John Sloan “View of the City from Greenwich Village,” oil on canvas 1922

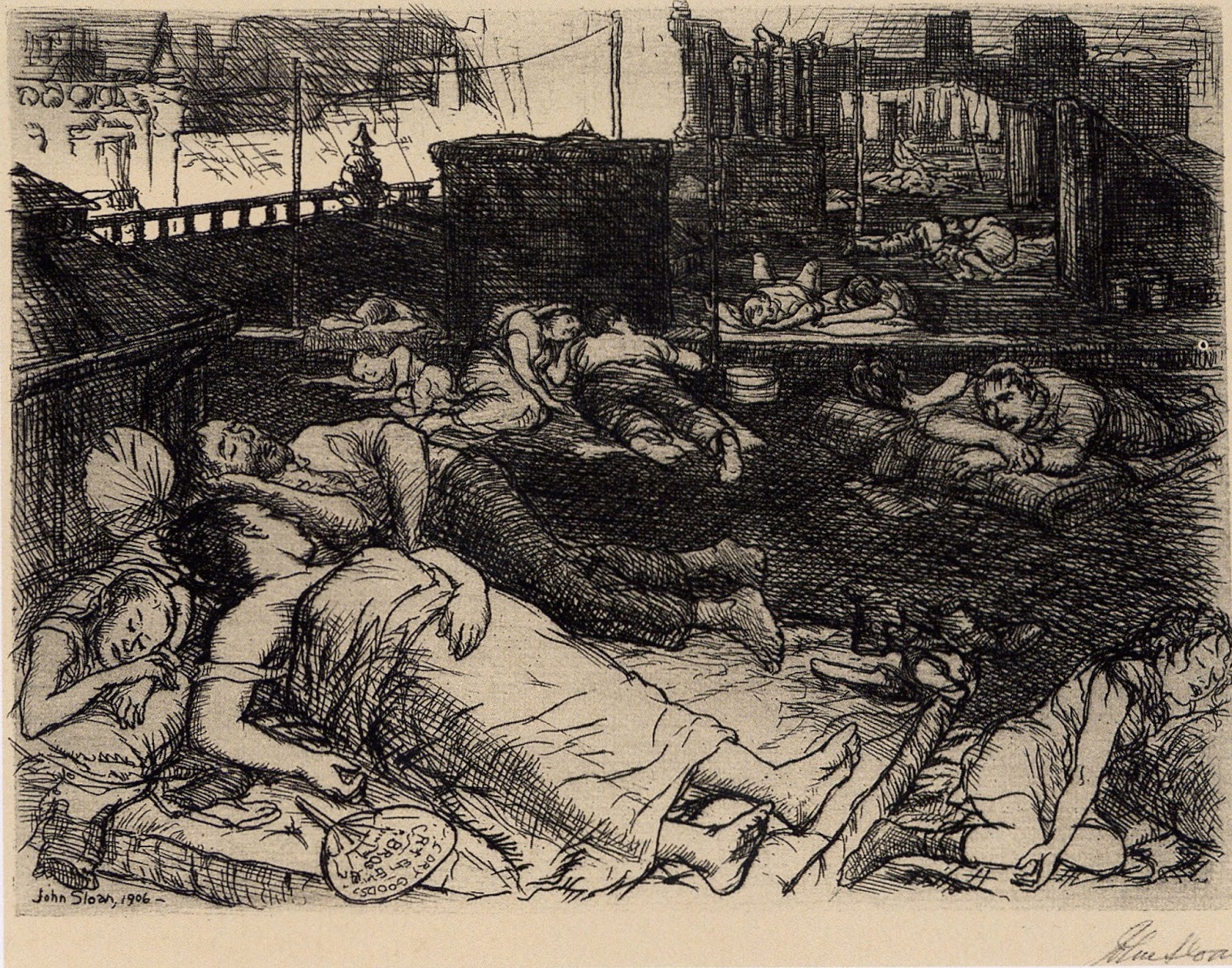

John Sloan “View of the City from Greenwich Village,” oil on canvas 1922 John Sloan. “Roofs, Summer Night” etching 1906

John Sloan. “Roofs, Summer Night” etching 1906

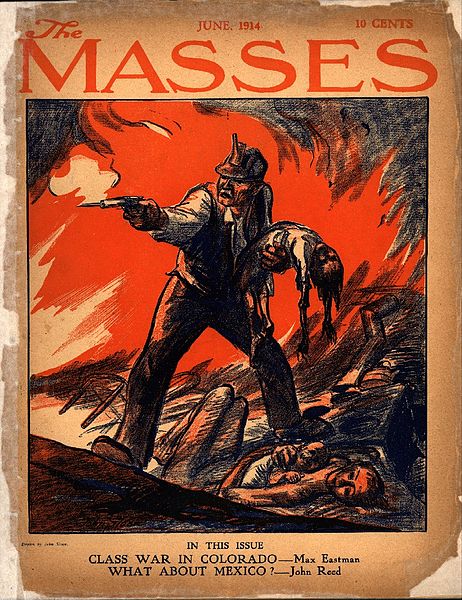

Sloan was a political artist as well as an acute social observer. Here’s a provocative cover illustration for the left-leaning periodical “The Masses.” It depicts a scene from the notorious Ludlow massacre. The tragedy involved

Sloan was a political artist as well as an acute social observer. Here’s a provocative cover illustration for the left-leaning periodical “The Masses.” It depicts a scene from the notorious Ludlow massacre. The tragedy involved

All photos by Kevin Lynch, except as noted.

All photos by Kevin Lynch, except as noted.

In the detail above, the Sperm whale teeth are nails inserted in a way I have yet to ascertain (not pounded through the bottom of the whale jaw). The eye is a door knob collar, the fin is a cut piece of soft metal, perhaps tin or aluminum. DiScalia apparently cut the sculpture from a slab of barn wood, and then whitewashed it. The way the whitewash has worn away seems like natural aging and exposure, because the two eye loops on which I attached the wall hooks are heavily rusted.

In the detail above, the Sperm whale teeth are nails inserted in a way I have yet to ascertain (not pounded through the bottom of the whale jaw). The eye is a door knob collar, the fin is a cut piece of soft metal, perhaps tin or aluminum. DiScalia apparently cut the sculpture from a slab of barn wood, and then whitewashed it. The way the whitewash has worn away seems like natural aging and exposure, because the two eye loops on which I attached the wall hooks are heavily rusted. Upon mounting Moby in my dining room, I thought I would also share a few photos of his new environment, which includes several other art pieces. On the wall adjacent to Moby Dick is a pure kindred to him (see photo above). It is a reproduction of Sam Francis’s wondrous 1957 abstract painting “The Whiteness of the Whale” which resides in the collection of the Albright Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York. It is the first work of art (reproduction of) that I ever had framed, many years ago.

Upon mounting Moby in my dining room, I thought I would also share a few photos of his new environment, which includes several other art pieces. On the wall adjacent to Moby Dick is a pure kindred to him (see photo above). It is a reproduction of Sam Francis’s wondrous 1957 abstract painting “The Whiteness of the Whale” which resides in the collection of the Albright Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York. It is the first work of art (reproduction of) that I ever had framed, many years ago. Finally, I return to the closest companion to the wooden Moby wall sculpture, right below him — one of my personal favorites among the sculptures I have done. It is an abstract bronze casting titled “Free Space Relief.” Note also to the left, a black-and-white reproduction on glass of a toreador with bull, by Picasso.

Finally, I return to the closest companion to the wooden Moby wall sculpture, right below him — one of my personal favorites among the sculptures I have done. It is an abstract bronze casting titled “Free Space Relief.” Note also to the left, a black-and-white reproduction on glass of a toreador with bull, by Picasso.

Kevernacular (Kevin Lynch) with his new Moby Dick wall sculpture. The small wooden jig-saw sculpture beneath the lamp is by Kevin. Photo by Ann K. Peterson.

Kevernacular (Kevin Lynch) with his new Moby Dick wall sculpture. The small wooden jig-saw sculpture beneath the lamp is by Kevin. Photo by Ann K. Peterson.