Ashcan Scene: “Sunset West Twenty-Third Street,” By John Sloan. Oil on canvas, 24+ inches by 36+ inches, 1905-1906. Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha Nebraska

Following our election year’s ongoing madness, I searched into not-too-distant modernism for something timelessly American and democratic that might feed our abused sensibilities. I found industrialized urban life – architecture and quotidian labors – graced by nature’s fulsome, inevitable beauty.

Look at the tenement scene above. The darker clouds float slowly by, like bloated scavengers, while below, on the roof of a tall building, a woman arrives to take down her hanging laundry, no doubt slightly begrimed by the city’s pollution. This is modern life burdened, but the single soul persistent, the circumstance artistically rendered akin to the blues sensibility.

The Ashcan School of American art has always been one of my favorite art movements. John Sloan is arguably the paramount artist in that group, which toiled around the turn of the 20th century, though Edward Hopper is more famous and it included founder Robert Henri and George Bellows among the artists who formed the movement’s core.

John Sloan “Self-Portrait in Gray Shirt” 1912 artsy.net

They were the first generation of artists to crucially value, capture and critique the urban American experience in all its grimy truth, as bleak as it was a-tree-grows-in-Brooklyn beautiful. Few artists have mustered better the shadow-shrouded atmosphere that would become later known as noir. The quality was probably first identified with the German Expressionists in the period after World War I, but imported to the U.S., where it would flourish in greater freedom than in its native land, from 1940s in film, television, and visual art, onward to the present.

The Ashcan School was a concept notably derived from Sloan’s nocturnal grittiness. And inside the modest nominal symbol sat an indelicate joke, a humble yet rugged functionality, capable of both containing and emitting olfactory auras that conveyed the profound decay of the American Dream, amid the vast exploitation of land and people that The Industrial Revolution evolved into.

The painting I chose to represent the movement, Sloan’s “Sunset West Twenty-Third Street,” is the only the second image I have used simultaneously for both my blog theme image and my Facebook page “cover photo.” That says something about how much I value the best and truest qualities of The Ashcan School, including Sloan’s environmental awareness here, and elsewhere. It’s not necessarily the best example, but it struck me as I rediscovered it in the Google search alluded to above. 1

One caveat. I don’t think this muted reproduction of the painting (above) from the website of the institution that owns it, The Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, does justice to the painting’s palette colors. I suspect the person who edited the Google image chose to dress it up with much brighter colors than the original. And the difference between those two palette approximations measures the difference between conventional notions of aesthetics and the Ashcan artists’ determined ability to probe and dig beneath the surfaces of urban presence.

Either way, there are other strong aspects countering all the darkness and implicit heaviness – qualities that give Sloan more vibrancy and hope than Hopper, the great poet of solitude. Even with a sole human, Sloan infuses a layered lyricism, in the rhythmic suppleness of the lighter clouds, and the sky’s richness, whether it is bright or muted. And the woman’s figure is burdened, yet maintains a strong, resilient backbone, and the hanging clothes retain a certain playfulness. More, the deep space before her is an interplay of angles and glittering vehicle lights, into a near-imperceptible horizon that still reveals sculptural mutations. Her superbly rendered and located figure suggests her eyeing this alluring beyond with a sense of longing for escape.

Formally speaking, Sloan risks betraying a primary compositional rule here, that is: avoid placing a large object in the center of your composition. He just barely sidesteps that by locating the stolid building silhouette just left of center. Still, it visually dominates the scene. But the hulking mass (a cast-off from Carl Sandburg’s famous “city of broad shoulders”?) stands there to signify more than lend pure formal beauty. In fact, pushing hard against beauty is virtually its raison d’etre here.

And yet, the long ledge of the foreground roof, with it’s strong leftward hitch, helps pull the compositional tension off center.

So it is work that is more radical than it might seem, given that it’s clearly part of the long tradition of landscape art, as it morphed into cityscape.

It is the humanity that gives the scene its life, through the eye of the artist and, by extension, the woman. That truth is underscored by the reality that this scene is actually Sloan’s own apartment building, and the depicted woman is his own wife.

“These wonderful roofs of New York City bring me all humanity,” Sloan was quoted as saying in 1919. “It is all the world.” 2

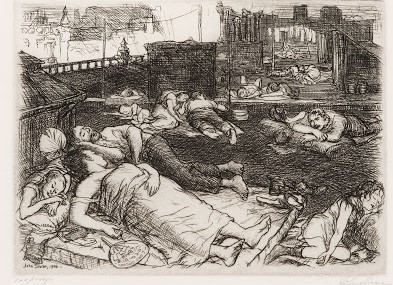

“Roofs, Summer Night,” is a further example of Sloan’s fascination with humanity, in the era of “big shouldered” cities, and is almost voyeuristic but clearly empathetic. I first saw this etching at the Chazen Museum of Art in Madison years ago, and it was done the same year as “Sunset.” Today it evokes the situation of immigrants, wherever their harsh limbo may be, floating above reality in their dreams, but only there.

John Sloan, “Roofs, Summer Night,” 1906 https://deepartnature.blogspot.com/

Is there something more in the greatest of Ashcan Art which, humble as it might seem, is clearly an early modern American art of cinematic scope, before color film.

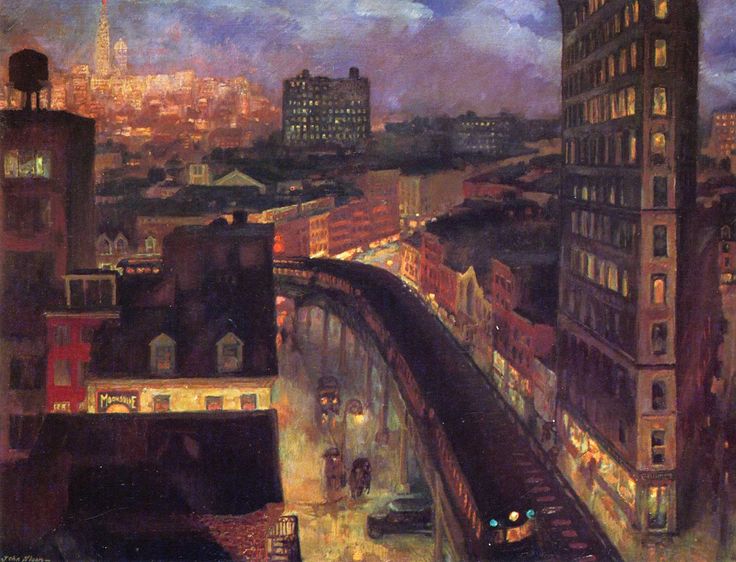

Now, take in an even more famous Sloan cityscape, from 1922, City from Greenwich Village:

John Sloan, “City from Greenwich Village,” National Gallery of Art. Pinterest

In another deeply storytelling perspective, the train helps tie the city’s society and commerce together, but spews its fumes into the most famous urban neighborhood of Manhattan.

I might toss the Ashcan cultural connection forward, a bit like Stanley Kubrick’s ape tosses his jawbone up into time where it descends as a space capsule. No grand scope quite so obvious here, but still these, and other Ashcan cityscapes, do explore human and environmental dualities that Andrew Delbanco recently attributed to Kubrick in his masterpiece film 2001: A Space Odyssey: “a tribute to the collective genius of humanity for having turned this merciless world into a place fit for human habitation. It was also a merciless assault on the delusion that the world is susceptible to human will.” 3

____________

1 Consider the catalog book John Sloan’s New York, by Heather Campbell Coyle and Joyce K. Schiller, for a Sloan exhibit that originated at the Delaware Art Museum in 2007. Though Sloan’s “The City from Greenwich Village” (above) is the frontispiece, “Sunset” is the sixth color plate in their text, on page 37. The authors see it as Sloan transferring his “awe” to his wife.

2. The Palmer Museum of Art at Penn State organized a major exhibition on John Sloan, “From the Rooftops: John Sloan and the Art of a New Urban Space” in 2019, which also traveled to the Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, New York. https://news.psu.edu/story/553028/2019/01/07/arts-and-entertainment/palmer-museum-art-announces-major-show-ashcan-schoolhttp://

Google reproduction of the Sloan painting:

John French Sloan https://www.tuttartpitturasculturapoesiamusica.com

3. Andrew Delbanco,

Christopher Porterfield on the road. milwaukeerecord.com

Christopher Porterfield on the road. milwaukeerecord.com