James McMurtry. Courtesy Texas Monthly

James McMurtry has embarked on his first tour in several years. He will perform solo in dates running through April, then continue with his band in May, on a tour running through the end of July.

Upper Midwest McMurtry dates include April 22 at Old Town School of Music, in Chicago, June 11 at the SPACE, in Evanston, June 12 at Shank Hall in Milwaukee (https://shankhall.com/), and June 14 at The Ark in Ann Arbor.

Here’s the full tour list: https://www.highroadtouring.com/artists/james-mcmurtry/itinerary/

Imagining James McMurtry in his element: He squints hard, and sees humanity and the world with laser vision, in the cruel Texas-glare sun, amid imperious cactuses. Flies buzz like hungry little devils. James coughs in the dust, but a man knows what he’s gotta do. Especially if he’s as driven as he is. He could drive a cattle herd across that behemoth state, and beyond, like the one his father Larry McMurtry famously depicted in his famous novel Lonesome Dove.

But such epic drives are rare now, as cattle growing and marketing are bad for the planet. James knows this, even as he commemorates, partially in Spanish, a deceased cowboy friend and his tradition in his recent song “Vaquero.” So, he turns off his vintage Ford Falcon convertible, peers at the horizon, the hot wind rippling his long gray hair. He lifts his cowboy hat, wipes sweat off his grimy brow, then plops the hot hat right back on. Part of him wishes he has a horse raring to go, instead of a smelly old car. So, he reaches over to the passenger seat, unbuckles his 12-string Gibson acoustic guitar, climbs out, leans against the car, and starts up a big sky-type chordal pattern.

He sings, “No more buffalo…” This thought he seems to care about greatly, as metaphor and as reality. Why and how? The guitar has plenty to do with it.

James McMurtry at home: He ended another Livestream pandemic solo home concert recently with that song, set his guitar down and said “thank you” to the silent audience that can applaud only with Facebook comments. I think “No More Buffalo” is something of a signature song, and I think he feels that way, too. You could make an obvious case for “We Can’t Make It Here,” too, or perhaps “Just Us Kids,” or “Choctaw Bingo.” The majestically big-picture “Long Island Sound” and one troubled man’s stunningly confessional “Decent Man” are more recent candidates.

(As far as I know, McMurtry’s “Live with Restream” home solo concerts are only available on his Facebook page, which you can follow: https://www.facebook.com/watch/JamesMcMurtry/)

But those songs are mostly anthemic, and clear hallmarks, whereas James is also an expert in understatement, of tracing the shadows of the underserved. Among his more indelible intimate American portraits is the stoic loser of “Rachel’s Song,” who might be quite typical of many contemporary divorced people, stumbling along spiritually on a deserted street. It’s telling that Jason Isbell, a younger talent of superlative songwriting skills, has covered this song, with tender insight.

As an American troubadour McMurtry rivals any we know today. But he’s also only the peculiar kind he’s capable of being. That happens to involve an atypical genius which has been insufficiently addressed to date, in its artistic fullness.

Indeed, the often-surly glory of his artistry is piling up just a bit: Not only have I not yet written about his latest album The Horses and the Hounds, but I’ve also come to realize that his fullest artistry doesn’t just lie squarely on his most salient talent, the lyric-endowed song.

McMurtry started playing guitar at age seven (first taught him by his mother, an English professor) but didn’t start writing songs until he was 18, he has said.

The stereotype is the gifted singer-songwriter as a type of literary whiz. We don’t associate their guitar-playing and songwriting skills as part of a shared prism of expression and narrative, especially coming out of the folk tradition, where a songwriter is expected to do little more than simply strum through simple chord changes.

James McMurtry performing “Down Across the Delaware.” Courtesy YouTube.

Today McMurtry seems, song after song, compelled to self-accompaniment as integral to his storytelling technique, like a sonic cinematographer, or musical dramatist. He’s never showy, yet the guitar can pull you into his distinctive musical world with a magnetic force and, when he’s playing 12-string, his rhythmic patterns and pulses sparkle with harmonic auras that can be stunning. His guitar blends rhythm playing, rich chording, and finger-style adornments. His digits tell their own story yet boost and entwine his songs, which explore a variety of cadences and moods, in well-observed and psychologically resonant narratives.

He admits he takes his sweet time writing songs. But performing his songs, with glimmering and chiaroscuroed backdrops, seems a weekly task of this troubadour, with his well-oiled work ethic. Witnessing that online has been a precious upshot of the COVID pandemic’s forced social distancing.

So, the realm of that interactive song-guitar dynamic is where we must assess McMurtry. He may be the greatest songwriter now working in his prime – one video-watcher, himself a songwriter, called him “The Dustbowl Dylan … and the best everyman songwriter alive.”

Yet McMurtry might also be our greatest singer-songwriter/self-accompanist, capable of extraordinary yins to his yangs. That’s why his assessment as an artist must be recalibrated. A comparable songwriter and more gifted singer, Willie Nelson, also is an extraordinary guitarist, but sort of when he wants to be – periodic fluent solos between verses on his battered old guitar named Trigger.

Another artist who comes to mind in comparison is Leo Kottke, but Kottke is known primarily as a virtuoso fingerstyle guitarist. If McMurtry set his mind to it, I think he could do a guitar-oriented set like Kottke does.

This has much to do with the virtuosity and artistry he has refined, especially over the last year and a half at his home. He has performed Livestream with skilled diligence each Wednesday and Sunday. This is a logical extension of his weekly, self-imposed Wednesday night gigs at Austin’s Continental Club, whenever he’s not touring. 1

This recalls somewhat our greatest living songwriter, Bob Dylan, because they both seem driven to constantly work or tour, Dylan especially at an advancing age. We should remember what Thomas Edison famously said: “Genius is two-percent inspiration and ninety-eight per cent perspiration.”

***

I first became aware of the synchronicity of McMurtry’s guitar playing and song-craft when I got a 10-feet-away seat for a solo acoustic recital at Milwaukee’s Shank Hall in 2014. Here was my immediate response:

“Friends, it was Thursday at Shank Hall in Brew Town and James McMurtry was dealin’, alone, with nothin’ but a 12-string guitar. That surprisingly stacked the deck for a show that rated four aces, period. He’s so skilled – playing bass accompaniment to his typically deft figurations – that I never missed his band. At times, the 12-string’s shining harmonic resonances at a fast-chugging tempo sounded like a chrome-plated locomotive at full speed. Best 12-string playing this side of Leo Kottke.”

I’ve seen only brief video-response comments on McMurtry’s solo acoustic performances during the pandemic; we are more aware of his electric playing with his band. A singer-songwriter named Sean, the same person quoted about the “Dustbowl Dylan,” also comments: “Sometimes you can tell the road has worn him down a bit, but his guitar playing is always the driving force of his band. His electric sound is effortless, full, and he can create an amazing sustain.”

So, attention must be paid: McMurtry’s self-accompaniment has become even more deft, fluent, and effective as the driving force of his songs. It’s as if he insists on sustaining a strong or at least simpatico heartbeat for even his most diminished characters, like the nameless, quietly desperate person in “Cutter,” bereft yet clinging to better memories. The song – which also poignantly reflects the too-common gulf of understanding between even close friends – closes Complicated Game with stunning power.

I hope McMurtry considers shepherding and curating a dozen of the best solo acoustic songs he has Livestreamed in recent times for an album. Now that would be something, quiet but deeply resonant.

You see, I’m shifting gears: To fully contextualize my focus on his guitar-to-song-singing synchronicity, I need to delve properly into the depths of his song-writing prowess.

So, as I said, “No More Buffalo” (from the fatefully titled 1997 album It Had to Happen) is, too me, one of the great environmental protest songs we have. 2 It’s so good because it starts with a chest-filling chordal statement that portends something, in a G-D-A-G progression. The song sustains or suspends on that major key sequence until a few anguished B-flats, most tellingly on the phrase “I swear” on the late-in-the-song lyric: But man, they were here, they were here I swear. Yet, McMurtry sort of sidles up to that point, by telling a story of a group of graying guys who probably haven’t changed their ways in just about forever. But at least one of them remembers and feels something and sees how things have changed. So, the song’s narrator finally tunes into the problem. But see how the revelation sneaks up on him:

We headed South across those Colorado plains

Just as empty as the day

We looked around at all we saw

Remembered all we’d hoped to see

Looking out through the bugs on the windshield

Somebody said to me

(chorus) No more buffalo, blue skies or open road

No more rodeo, no more noise

Take this Cadillac, park it out in back

Mama’s calling, put away the toys

The narrator now remembers and believes, too – just maybe the noble, hulking giants are still out there. He continues until this interchange of voices:

I never thought they’d ever doubt my words

I guess they were just too tired to care

I’d point to the horizon, to the dust of the herds

Still hovering in the air

Somebody said it ain’t any such

Man you wish so hard you’re scaring me

‘Cause those are combines kicking up that dust

But you can see what you want to see

And go on chasing after what used to be there

Top that rise and face the pain

But man, they were here, they were here I swear

Not just these bleaching bones, stretching across the plain

Those anonymous “somebody saids” make the rhetoric work, persuasive without haranguing, or preaching. “Somebody” could be anyone, or his own subconscious and memory reflecting each other. So, we feel the loss, as if the hoary bison embodied something invaluable in life. Even the rodeo, the celebration of Wild West conquerors who helped desecrate the land and its creatures, and committed genocide of Native Americans – even the mano contra toro — has become passe.

And by the end, the title refrain, one more time, has gained momentum, a power you feel in your own bones. It’s like their car is speeding up, hurtling towards a horizon falling to the abyss of irrevocable passage. Since I heard it and it sunk in, I’ve never been able to think about the buffalo or the travesties and waste of The West without McMurtry’s song ringing in the back of my head.

This is a band performance of “No More Buffalo” but McMurtry, as usual on this song, plays acoustic guitar. Along with those chords, Daren Hess’s bass drum and tom toms open the song, resounding like cracks of revelation in a gorge of environmental ignorance. Then, listen to those drums, a brilliant stroke, rumble through the song, just like the tromping thunder of the great vanquished herds. This piece slays me every time, earning its emotional impact every step of the way. 2

***

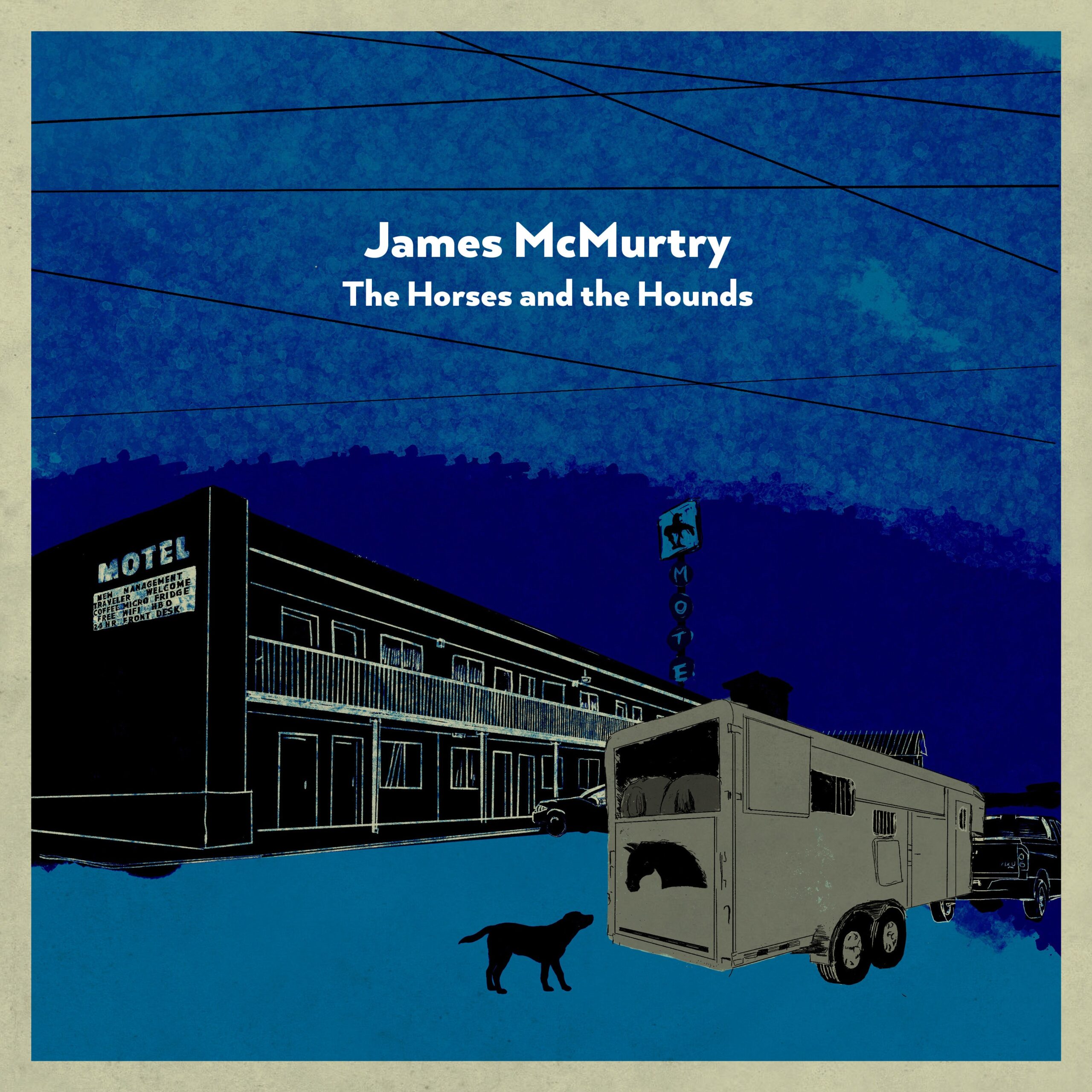

Courtesy New West Records

This brings me to his latest album. The titular phrase, “the horses and the hounds,” recurs as several meanings. Ostensibly it seems to tell – as the wonderfully blue-tinged noir album cover does – of a working stiff who drives a horse-truck trailer. What other meaning? “The singer finally admits, “Still, I’m running from the horses and the hounds.” He’s running from horses? These magnificent, larger-than-life creatures, often with very close relationships with humans – can occur in dreams, a phenomenon artistically acknowledged as early as in Henry Fuseli’s famous 1871 painting “The Nightmare.”

Henry Fuseli’s famous 1871 painting “The Nightmare.” Courtesy fineartamerica.com

As for the hounds: There’s always the mythical hellhounds that bluesman Robert Johnson endured, and maybe helped chase him to his early grave. They sure haunt his legacy and the blues tradition. It’s an enduring metaphor for psychological affliction or terror.

Hellhounds on the trail of blues legend Robert Johnson. Art print by Elena Barbieri. Courtesy INPRINT

McMurtry also often trades in the interface of hard-grit reality and troubled dreams or memories. He talks about one of the new album’s most substantial songs, “Decent Man,” a story that might give any man in this situation nightmares.

McMurtry reimagines a Wendell Berry short story, which derived from Woody Guthrie’s song “Tom Joad,” itself a musical portrait of the protagonist of novelist John Steinbeck’s Dustbowl tragedy The Grapes of Wrath.

The “decent man” is the guy the narrator kills with a .38 pistol. No less than his best friend. It’s unclear why he shot him, but he circles semi-coherently around his mental state:

“If the truth be known, I wasn’t doing that well/ I wasn’t paying attention, I brought it on myself/ and I blamed it on the gods that seem to smile on everybody else/ I got so inside out, I didn’t know what was real.”

That sounds like what? Maybe like too-many men in tough life situations where a conflagration of circumstances put them in a paranoid or aggrieved state, and a gun is too easy to reach for, and to irrationally think it will solve a complicated problem. It usually makes thing worse, much worse. It’s an all-too American dilemma and tragedy, repeated with shocking, even numbing, frequency.

Listen: My fields are empty now/ my ground won’t take the plow./ It’s washed down to gravel and stones./ It’s only good for buryin’ bones. That is the song’s actual chorus, one of the most devastated choruses you’ll ever hear. It’s a murder ballad of uncommon ingenuity, yet understanding of common human foibles, and suffering. And loss. Most of all.

In McMurtry’s version of the story, the killer’s daughter, named Lola, visits him in jail. She still loves her dad, despite the horror of his deed, and that bothers the prisoner as much as the crime itself. His own daughter’s love throws this man off balance so that he must reconsider his still-fresh self-loathing. “I don’t know how she even stands to look on her daddy’s face,” McMurtry sings. There’s no better way to comment on this story than the songwriter’s summation: He was more than just a decent man/ best friend I ever had./ When you’re shooting at a coffee can/ a thirty-eight don’t kick that bad. / But it kicks right through my bones every second of every day/ clacking by like cobblestones under broken wheels.”

Even if he’s profoundly affected, in shock, he still doesn’t seem to know why he did it. Because life is too confusing or abject? Does that disquieting possibility offer any hope for absolution or healing?

It’s powerful stuff. How does Lola really feel? And the victim’s family? And “poor dad?” – The song strives for some empathy for him.

Laurence Fishburne played Socrates Fortlow in an HBO adaptation of a Walter Mosley novel. IMDb

The killer recalls Socrates Fortlow (pictured above), a fascinating murder/rape ex-convict created by novelist Walter Mosley who never understands the reasons for his crimes, yet becomes a street philosopher of redemptive power, while always remaining “at risk.”

McMurtry credits Horses producer Ross Hogarth who “probably got the best vocal performances I’ve ever done.” On “Blackberry Winter,” in his upper singing register, McMurtry is his most emotionally engaged.

A man looks back at the seeming end of his primary relationship, and having to refuse his woman, who apparently still has feelings for him, “to tell her no, to tell her no.” It’s a tough task to do at once, emotionally at least. And does he really need to? “Blackberry winter” is a Southern term for damaging early spring freezes, after blackberries have blossomed. Couldn’t he see if some berries – from the original branch their relationship grew upon – are still salvageable?

McMurtry is expert at painting pictures of troubled, just-barely-getting-by common folk, in the era of American democracy in peril. Or so it seems, with working folk still struggling while the rest of “the economy” – investors, Wall Street, big business, etc. – seems to flourish. Many of these working folk are now Trumpsters, sadly, because they had nowhere else to turn, feeling their dreams are threatened. So, they hang onto common biases of white fear or “supremacy,” as a psychological crutch holding up a nominal ideology.

Trump – a successful faux television demagogue to whom the Electoral College handed the keys to The Bully Pulpit – understood, voiced, and “validated” their grievances. The Democratic Party had forgotten about them a long time ago, as Thomas Frank argues cogently in “Listen, Liberal: Whatever Happened to the Party of The People?” So, the song’s emotional impact radiates like an extended electric shock, about a characteristic state of American being. It poses the implicit question: Do you know someone like this? Might one of these people be you?

What are we gonna do for these people? Will politicians ever address their concerns and suffering honestly, instead of only as an election ploy? Frank argues you won’t get it from the contemporary professional upscale liberal (think of Silicon Valley culture and comparable ones) where funding and values go to support entrepreneurship and “innovation” that does little for the plight or incomes of ordinary folk.

These may even be “innovative” ways to exploit them. Of the working class, these elevated folks think that, if you don’t have a college degree, it’s your fault, Frank explains. Even teachers, by their thinking, are suspect professionals, beneath their value system. The current Democratic party has shifted closer to addressing the huge lower end of the equality gap since Frank’s 2016 appraisal, but in 2022 President Biden hasn’t yet substantially addressed racial justice and other issues crucial to inequality, to bridge the political gap Democrats helped create for Trump to exploit and widen. Inflation and high gas prices don’t help, even if the latter helps the effort to protect Ukraine from Russian invasion.

The narrator of “Blackberry Winter” might be telling her “no” because he can’t afford to support her, or some other circumstance of a tough life, devalued and forsaken. McMurtry’s characters often live close to the edge, like so many Americans. “And tell you no,” isn’t delivered in a way suggesting any disdain, based on a contaminated relationship. In this vocal register he sounds a bit like Jackson Browne. 3 So there’s a plaintive weariness beneath his straightforward talk, which also conveys something palpable and spiritual, and common to humanity, like “everybody has holes to fill, and you know those holes are all that’s real,” as Townes Van Zandt. once sang.

McMurtry is akin to fellow Texas troubadour Van Zandt whom he’s covered him from time to time – he does covers very occasionally — including Van Zandt’s “Rex’s Blues” on his 1998 album Walk Between the Raindrops and on his live 2004 album Live in Aught Three. 4

In a 2019 interview, McMurtry commented on America’s current tribalism: “Everybody wants to feel a part of something. They are in a group thing. They don’t want to think individually. It’s easy to make money off of that. It’s not just American, it’s human. It’s always been like that…

“It’s hard-wired caveman stuff. We have to learn how to think our way around that. Basically, our minds will have to evolve faster than (our) simian brains are able to evolve on a cellular level. That hard wiring is going to stay in there unless we learn to short-circuit it in some way, or we are just going to perish.” 5

In solo renditions of his newest songs, his guitar-playing’s fluent sense of rhythmic propulsion and drama, and his quirkily apt harmonic changes – which sometimes recall those of Joni Mitchell – cast just the right tone, emotional grist, and gravitas. The Horses and the Hounds has plenty more character-packed scenarios, no more poignant than truck-driving “Jackie,” whose fate ambushes the listener with McMurtry’s matter-of-fact tone. And yet, there’s also the self-deprecating comic relief of “Ft. Walton Wake-Up Call.” After doing “Decent Man” and “Jackie” consecutively on a Livestream, he peered at his setlist and muttered, “Well, I got a bunch a’ real downers in here this time. Break out the Prozac.” His speaking delivery is as dry as tumbleweed too old to tumble.

The Horses album, with old drumming mate Darren Hess and a bunch of studio aces, is a continuation of a major artist at the peak of his powers, who seems philosophically bittersweet, slyly heartfelt, and still cranky enough, and still comparatively obscure, given his talents. He’s capable of very catchy songs, but his ordinary-Joe voice always earns its emotional truths, and he’s no attention-seeking self-promoter, so he never compromises his art. In that way, he may be keeping himself close to the real people reflected in his characters.

His music is a vivid way to refocus reality to where our social responsibilities might best align. With “the people.” McMurtry’s seemingly forgotten folk dwell low in societal shadows, with some, in effect, face-down in American dirt, because you can’t get lower, without being buried alive.

_____________

(Author’s note: This essay was submitted to nodepression.com, which didn’t accept it because, they said, “We don’t publish essays on individual artists.” Ironically, the first article they ever published of mine was also an essay of comparable length. Their editors have since changed.)

- I’m not a guitarist, so I won’t get gear-geeky here. But I’ll report that, on his Livestreams, McMurtry regularly alternates among four (or five) acoustic guitars: a 12-String Ovation, a 12-string Fender, a red 6-string Guild, and, I believe, a 6-string Fender. Sometimes he pulls out a big, dark brown 8-string baritone guitar, which he refers to as “The Beast.” In November, he used it to play the title song from The Horses and the Hounds. He seems to have slight preference for the 12-strings.

- Buffalo appear to be making a comeback. I’d like to think McMurtry’s song, released in 2007 made some difference in consciousness and action.

- “No More Buffalo” is also on the 2007 collection, James McMurtry, The Best of the Sugar Hill Years.

- Perhaps not coincidentally there’s an influence. McMurtry recorded most of the album at Jackson Browne’s Groovemasters Studio in Los Angeles.

- Caleb Horton, in a James McMurtry Primer blog, vividly explains the connection in the kinds of emotional impacts of their music: “The easiest way to explain it is that James McMurtry and Townes Van Zandt exist along a ten-beer continuum. McMurtry plays to that fourth beer, right before you decide to have six more, where you’re sitting down, and sadness somehow feels like the world’s only honest emotion. Van Zandt plays to beer number ten, where pharmacy vodka with a wolf on the label is in the cards and tomorrow doesn’t even exist because the sun’s down.” Horton continues. “Point is, I can only listen to Townes Van Zandt two or three times a year. The man’s music should come with a warning label…like they do with European cigarettes. James McMurtry is in the same tradition, but he opens the blinds in the morning. I can listen to him. And that’s how I recommend him to people.” Caleb Horton, A James McMurtry Primer http://bitterempire.com/james-mcmurtry-primer/

- Mary Andrews, “McMurtry Remains the Harbinger of American Truth,” Glide Magazine https://glidemagazine.com/228503/james-mcmurtry-remains-the-harbinger-of-american-truth-interview/

Christopher Porterfield on the road. milwaukeerecord.com

Christopher Porterfield on the road. milwaukeerecord.com