Ghosts can drag on our psychic heels interminably – that’s why they’re called haunting. Damn hard to shake. So Bob Dylan was utterly apt in titling his new 17-minute opus “Murder Most Foul.” He’s quoting perhaps the most famous haunter in literature, Hamlet’s father — murdered by Hamlet’s uncle, who then marries the prince’s mother and gains the Danish crown. At one point, the ghostly father whispers, “Murder most foul, as in the best it is; But this most foul, strange and unnatural.”

The ghost of Hamlet’s murdered father in the Kenneth Branaugh film adaptation of “Hamlet.” Courtesy Kristlinglistics

Dylan was apparently among the countless of both the so-called “greatest generation” and the baby-boomers who could never quite let go of the assassination of John F. Kennedy. And have we really, as a nation? Ever since that fateful day in Dallas, America has indulged a weakness for conspiracy theories. It’s hard to not argue that Kennedy assassination isn’t the primary impetus for a collective national neurosis — the Warren Report be damned. I have an intelligent friend with a license plate that reads simply: “JFK,” and who eagerly unfurls intriguing conspiracy tentacles on the subject. I’ll admit I wrote one of the first poems of my young life, and then read a whole book, about the assassination back in the day. 1

So, we struggled mightily with the tragedy of it, the insanity of it, the mystery, skulduggery and intrigue. It brought this barrel-chested nation crashing to its knees and wringing its hands, after Kennedy had lifted us up with a noble challenge, the dream of the moon, and hope for a greater America – not in xenophobic isolation like our current president – but through the Peace Corps, and diplomacy, in service to the world. Even in largely outmaneuvering The Soviets in the Cold War, though that almost went awry.

What a different world ours might be had Kennedy (and M. L. King and RFK) lived to fulfill their promise and vision. Instead, we soon got the “Reagan Revolution,” neo-liberalism, and now, Donald Trump and his white-nationalist primary policy-maker, our currents state of affairs.

Rolling Stone is straightforward in striving for the song’s currency, certainly at an emotional level: “All across the country at this very moment, people are lost, scared, and grieving. The coronavirus crisis has transformed American life with shocking speed — and Bob Dylan wants you to know that he feels your pain,” asserts Simon Vozick- Levinson. 2

For sure, by transporting us with such skilled empathy, Dylan transfers our neurological focus away from our pain, in a similar way that certain tried-and-true medications, such as medical marijuana, work for countless people suffering chronic physical pain.

Dylan releasing this now also might help explain why, after becoming the unofficial protest spokesman of the ‘60s generation, he abdicated the role increasingly in the few years after Kennedy’s death in November 1963. He clearly cares that people hear it now, as if finally unburdening himself. 2

The summer of 1964 brought Another Side of Bob Dylan which stepped back from the heavy protest of The Times They Are a’ Changin’, with the exception of the magnificent “Chimes of Freedom,” a sort of farewell hosanna to justice. And by 1965’s rootsier, more personal and romantic Bringing It All Back Home, Dylan’s also beginning to plug in, and he chain-anchors the album with the long, searingly bleak “It’s All Right Ma (I’m only Bleeding)” which remains it’s very own surreal rough beast slouching toward Bethlehem. Yet, in retrospect, it’s chant-like manner and lyrics might also resonate as a conceptual trial run for “Murder Most Foul.” Consider the earlier song’s: “Disillusioned words like bullets bark/ As human gods aim for their mark/ made everything from toy guns that spark/ to flesh-colored Christs that glow in the dark/ It’s easy to see without looking too far/ that not much is really sacred.

While preachers preach of evil fates/ teachers teach that knowledge waits/ can lead to hundred-dollar plates/ Goodness hides behind its gates/ but even the President of the United States/ sometimes must have to stand naked.”

This new piece won’t be everyone’s cup of tea; Dylan doesn’t even sing a single melody. It’s more like a minister’s funeral sermon. Yet, his voice is richly nuanced, by turns, ironic, quizzical, tender and garrulous. At the very least, let’s agree his bard’s technique remains peerless, including his uncannily effortlessness at rhyming couplets, which keep our mind almost helplessly hooked at his words’ rhythmic resonance.

Dylan contemplates what we lost by paraphrasing Kennedy’s most famous aphorism: “Don’t ask what your country can do for you…” and soon follows by yoking bluesman Robert Johnson with Shakespeare, ”I’m going down to the crossroads try to flag a ride/ the place where faith, hope and charity die…“What is the truth, where did it go? Ask Oswald and Ruby they oughta know. Business is business and it’s a murder most foul.”

Jackie Kennedy reacts to her husband being shot. Courtesy The Conversation

Arriving at the decisive moment, Dylan pulls a masterful trick by inhabiting JFK:

Riding in the backseat next to my wife

Heading straight on into the afterlife

I’m leaning to the left; got my head in her lap

Hold on, I’ve been led into some kind of a trap.

The songwriter, creator of many unforgettable characters who’d be nobodies if not for him, learned long ago the power of rhetorical illusionism. Of the assassination itself he comments, “The greatest magic trick under the sun/ perfectly executed, skillfully done.”

A simulation of the gun sight of JFK’s assassin. Courtesy The Guardian

The Abraham Zapruder film, now replayed in slow motion, remains shockingly violent:

It’s a strangely compelling phenomenon – hearing the man who refused to speak for his generation doing what he can’t help but doing. Speaking for perhaps all generations, then and since, who cherish gifted, inspiring leaders. We feel we, too, must stand naked when they’re torn from us, as Martin Luther King Jr. and Kennedy’s brother Robert soon would be too. No wonder Dylan thought it was all too much for even him, or perhaps anyone, to fully grapple with then. Even now, he drolly disavows any special role: “I’m just a patsy like Patsy Cline.”

Nevertheless, his insight arises in several ways, including by changing points of view, so we look at life with a prismatic perspective. And it’s perhaps most powerful as emotional insight, well-honed empathy, a way of understanding the old rawness that remains, like heavy, rotting branches from our heart. Time heals, but somewhere beneath our psychic scars, many of us still carry a cross for our martyr, who carried an almost Christ-like aura, even if we knew his human weaknesses. Dylan curtly references the famous temptress who allegedly led two Kennedy brothers astray.

The instrumental accompaniment is also inspired, in its welling empathy and its softly buoyant restraint — from the most eloquent of instruments, the cello, and bowed bass, and piano. Lightly struck cymbals.

Yes, this feels like Dylan delivering the ghost of a beloved and blood-spattered leader into the existential consciousness of generations (Though Hamlet’s maker did as well, would that the poor prince been so successful):

“We’re right down the street, from the street where you live.

They mutilated his body/ they took out his brain

what more could they do?/ They piled on the pain.

But his soul is not there where it was supposed to be at

For the last 50 years they’ve been searching for that

Freedom, oh freedom, freedom from me

I hate to tell you mister, but only dead men are free…

Note the deftly swift switching of points-of-view here, as the author refuses to let us forget the horrid, cold-blooded nature of the deed:

Throw the gun in the gutter and walk on by…

Got blood in my eye, got blood in my ear

I’m never gonna make it to the new frontier.

The Zapruder film I’ve seen the night before.

Seen it thirty-three times maybe more.

Its foul and deceitful and vile and mean/ ugliest thing that you ever have seen

They killed him once, they killed him twice/, killed him like a human sacrifice.”

(Incredibly, Secret Service agent Clint Hill, on the Kennedy car’s trunk by then, reports that Jackie Kennedy climbed onto the hood not to flee, but to retrieve parts of her husband’s skull and brain matter.) 3

The Kennedy limousine in Dallas. Photo courtesy Getty Gallery

Dylan’s consolation is intermittent, almost as if only the innocent have earned it, by default: ”Hush little children you’ll understand/ the Beatles are coming, they’ll hold your hand.”

This nifty pop cultural reference preludes Dylan’s most inspired leap, an extended petitioning for grace even non-believers can understand. He invokes the period’s colorful, big-talking disc jockey Wolfman Jack, who hardly carries the gravitas of a Walter Cronkite. But Jack lets us down easier, we hope, in music’s healing waters. So hear Dylan, himself a disk jockey of note, riding his imploring waves, for the ghost’s sake and ours:

Wolfman Jack he’s speaking in tongues

He’s going on and on at the top of his lungs

Play me a song Mister Wolfman Jack

play it for my long Cadillac

play it that only the good die young,

take us to the place where Tom Dooley was hung…

Play it for me and for Marilyn Monroe.

Play please don’t let me be misunderstood

play it for the First Lady she ain’t feeling so good…

Play “Mystery Train” for Mister Mystery

for the man who fell down like a rootless tree…

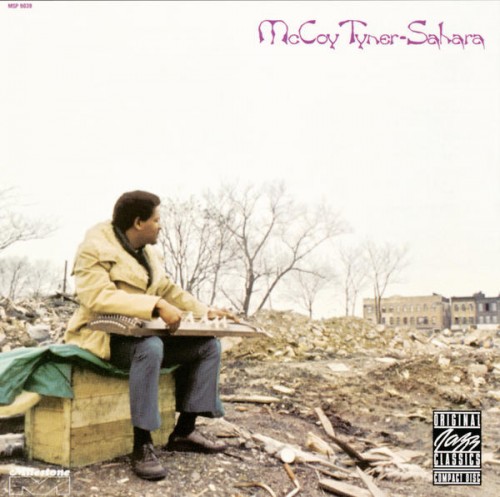

Play Oscar Peterson, play Stan Getz, play “Blue Sky” play Dickey Betts.

Play Art Pepper, Thelonious Monk

play Charlie Parker and all that junk.

All that junk and all that jazz

play something for the Birdman of Alcatraz.

play Buster Keaton play Harold Loyd

play Bugsy Seigel play Pretty Boy Floyd…

play Nat King Cole play Nature Boy”

Play “Down in the Boondocks” for Terry Malloy…

Don’t worry Mister President help’s on the way

your brothers are coming

there’ll be hell to pay.

Brothers? What brothers? What’s this about hell?…

Was a hard act to follow second to none

They’ll killed him on the altar of the rising sun…”

Marlon Brando as dock laborer Terry Malloy in Elia Kazan’s classic film “On the Waterfront.” Courtesy MarlonBrando.com

The riffing’s cumulative effect is stunning, deeply gratifying, as the songwriter/poet/disc jockey neatly ties it together at the end, like a spiritual tourniquet, that increasingly eases the pain built up over half a century.

Yet Dylan challenges us to reconsider, give this tragedy its full due, once more. How can we, as a nation and people, do better? At times, like now, our leaders need to lead. And yet, “Ask not what your country can do for you…” John F. Kennedy’s ghost might quote John Lennon: “Come together, right now, over me.”

But this work also feels healing, the work of a kind of doctor, a pop culture witch doctor perhaps, or a shaman, posing as a mere patsy.

We all know how Patsy Cline went to pieces. By doing so, she began to help us pick up our pieces.

And so, this patsy-priest helps us to walk, with that ghost, away from the altar, to our own rising sun.

_________________

- My “JFK” friend, a deeply involved aficionado of the assassination subculture, comments about official explanations: “An elaborate disinformation campaign by the CIA has led people astray at a Freudian level.”

- Here’s a Twitter message Dylan posted with the song’s release:

| Bob Dylan | |

|---|---|

| @bobdylan |

Greetings to my fans and followers with gratitude for all your support and loyalty across the years. This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting. Stay safe, stay observant and may God be with you. — Bob Dylan

March 27, 2020[1]

3. This video, narrated by SS agent Clint Hill, recounts the event with startling efficacy: