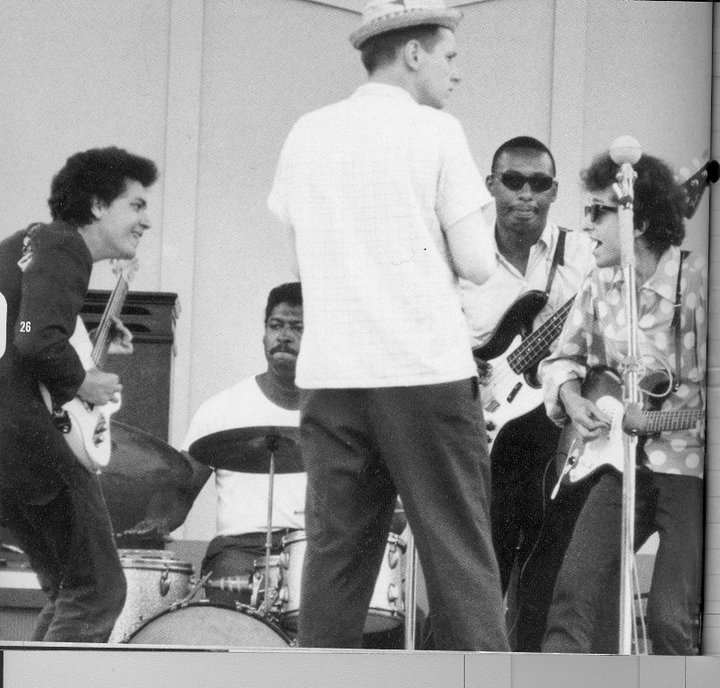

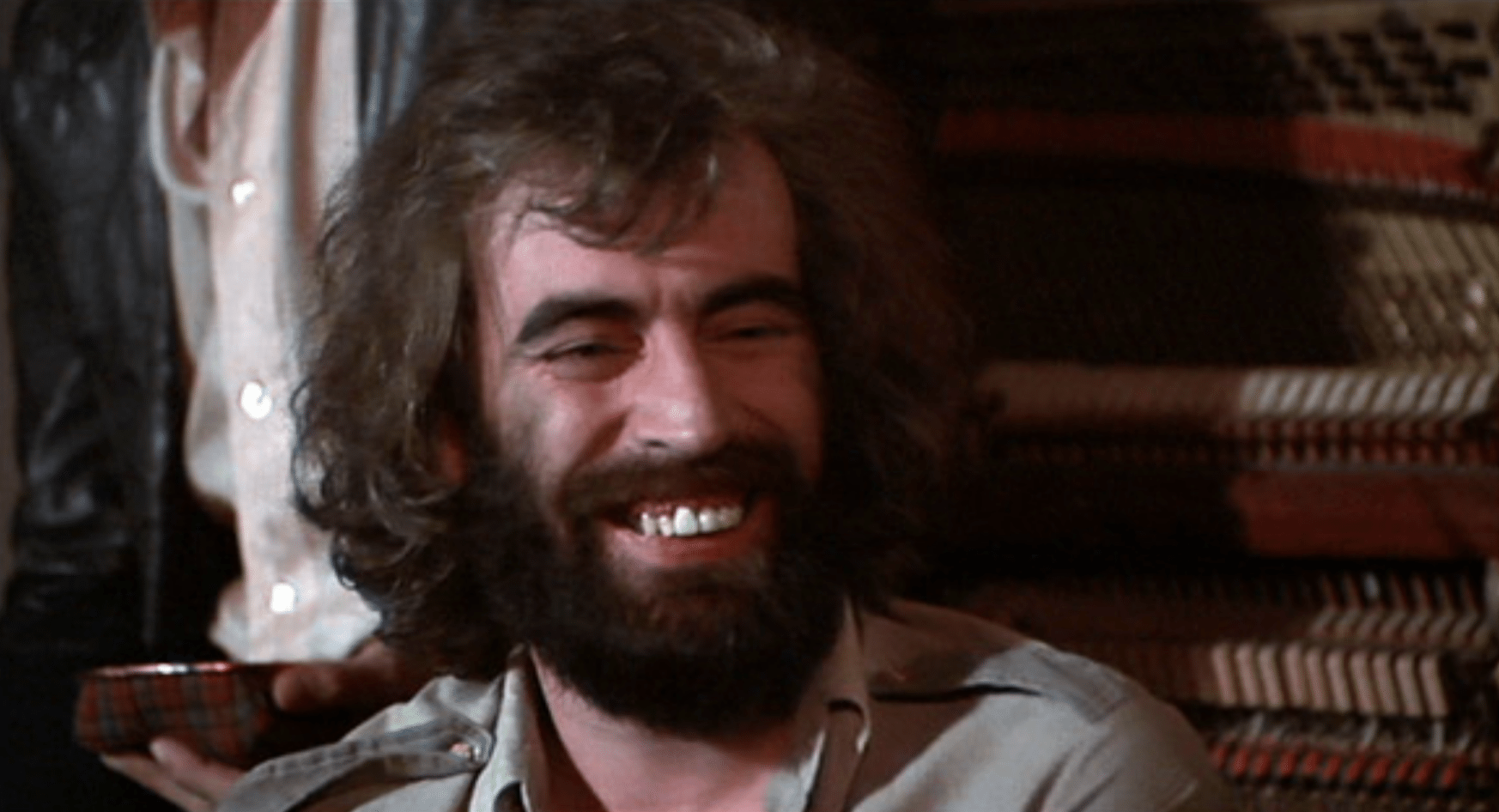

Eddie “Little Count Dracula.” Photo by Kevin Lynch

***************

Chapter 1: Taking “the leap” with a little black cat who thinks he can Fly.

It was the best of times, with our two aging cats, slowly and uncertainly getting to know each other. Then, it was the worst of times, though Ann and I had the best of intentions, when we brought “Eddie” into the house.

It’s debatable whether, for me and my gal pal Ann Peterson, it was “the age of wisdom,” as Dickens once proclaimed, to begin a famous tale. When I moved in with Ann last year, we instantly became a three-cat household, deeply exacerbating the absurdity of me being a cat owner my whole adult life, while being allergic to cats. Before too long, my asthmatic wheezing started getting worse, despite Ann’s assiduous dusting and vacuuming.

But Taj, her big, crazy black cat, got sick about five months after we moved together and, as cats will do, he died quite soon afterwards. It was a great loss I’m sure for Ravi, her creamy-white semi-Siamese scaredy-cat, who had been housemates with Taj since Ravi’s kittenhood. 1

Ann Peterson with our first set of three cats (L-R) Chloe, Ravi (in background) and Taj (facing Ann), before the black cat passed away. Photo by Kevin Lynch

But it seemed an even greater loss for Ann, I think. First of all, Taj was unbelievably attached to her. A “pet psychic” she had once hired, did a phone “reading” long distance and declared of Taj: “That is the neediest cat I have ever encountered.” He was persistently jealous of any book she was reading and tried to horn in past the book, to stick his face into hers, especially when she was reading prone, in bed. Ann loved and hated Taj’s clinginess in seemingly equal measure, and his often hyper-goofiness entertained her no end, well, until the end.

However, she is also the most squishy-hearted, animal-centric person I’ve ever met (She claims her two sisters are “worse” and, indeed Cary and Jennifer both own more pets than we do). She actually had two cats and two dogs when I first met her although, by the time she moved to the east side from Wauwatosa, the two dogs had died.

So, she began to make up for those losses by volunteering to walk dogs at the Humane Society on Saturday mornings. Now, she daily checks on the current dogs on her cell phone, to see which ones might’ve been adopted overnight and, to her great chagrin, which end up being returned to the Humane Society for not quite fitting into the household.

“Oh, Capone is back!” she cried out yesterday. Of course, you wonder why the dog ended up with that name. “But he’s the sweetest guy, so polite,” she always says of most any returning dog who apparently violates parole. Yeah, sweet like crafty Capone was, just before he pulled his gun to waste an old crony who’d betrayed him.

Ann promised me she would never again try to bring a dog into her house, despite all her angst and strong affection for these mangy, sometimes handsome, and eager dogs. So, I was hardly surprised the day she suggested we look for a kitten who might begin to replace the playmate/pal role that Taj made in Ravi’s life. By then it had become clear that Ravi and my cat, Chloe, though now beginning to peaceably coexist, would unlikely ever be close buddies, as Chloe had been in a one-cat household for so long.

So, I agreed to the idea, somewhat warily, and sure enough, Ann quickly found a three or four-month- old black kitten in a foster home, waiting for just the right real home.

We went to visit the cat — a lean, wiry shorthaired little critter, unlike the fat and long-haired black Taj. He was just as charming and crazy as you would expect a kitten to be, so we were hooked.

Chapter Two: Life (and Fear and Loathing?) with Eddie “Little Count Dracula” the cat.

When we brought him home, almost instantly all hell broke loose. I only slightly use the term figuratively, as it wasn’t long before the cat, whom we named Eddie, took on the role of a satanic intruder. I thought Eddie was a fine name, not because it’s my middle name, but because he right away reminded me of Eddie Haskell, the smart-ass neighborhood troublemaker on Leave it to Beaver. He even talked a bit like Eddie, with sort of a whiny, scratchy voice, not at all like my Chloe’s almost lyrical meow.

And when it’s time for chow he schmoozes me with intense body rubbings against my legs, just like Eddie Haskell would schmooze Beaver’s mom — “Good-afternoon, Mrs. Cleaver, you’re looking especially lovely today” — and might get rewarded with a piece of cake, despite having just dunked her son’s face in a mud puddle in the backyard. Otherwise, Eddie the cat often runs away from me because I’ve begun to become sort of the “bad cop” in our disciplinary efforts. Of course, that mad dash is at least as much his manic energy at work, as cat toys of all sorts bounce and skitter around the floor.

Ann and I quickly got dizzy watching Eddie zoom back-and-forth through our Riverwest flat, but that was laced with anxiety because Eddie was often chasing either my Chloe, or Ann’s Ravi, and usually tackling and roughing up the victim a bit. If it were football he would be repeatedly charged with a personal foul for unsportsmanlike conduct.

Eddie soon was creating chaos for all of us while, of course, charming us with his kittenish playfulness and goofiness. It’s as if he had memorized the book a cat is reading in a New Yorker cartoon: How to Be Very Annoying and Cute. Part of the problem and the charm is that Eddie seems to be an extremely smart cat, which is saying something giving the superior intelligence of the species in general. So, he’s crafty, stealthy, cunning, and seemingly, at times, cold-blooded. In other words, he’s an unrepentant scoundrel.

Okay, here’s a cute example of his smarts. He invented a game with one of the little sparkly squishy balls he and the other cats play with. When an empty laundry basket is on the kitchen floor, Eddie will toss the ball into the basket, and then tip the basket over sideways. So now the ball is caught in the side webbing of the basket. But rather than simply pull the ball out again, Eddie delights in the fact that it is “in jail,” perhaps like he should be. So, he starts pushing the tipped basket around and it rotates across the floor on a circular axis, with the squishy ball dancing around along its sides. Neither I nor Ann, another lifelong cat-owner, have ever seen a cat do such a thing.

Watch Eddie in action: Eddie and the rolling basket

On the downside, at the most, shall I say, existential level for me, my asthma was once again getting worse, with three cats and Eddie often infiltrating our bed at night. Oh joy.

So, for my health and Ann’s relative nightly peace, we’re trying to keep Eddie out of the bedroom at night, another challenging “game” the elusive rascal’s too good at. Even when we successfully get him out of the room, our early morning slumber is often roused by the unnerving sound of Eddie jiggling the doorknob, trying to open it. If he had opposable thumbs, I would readily imagine him, already up on his hind legs, marching in upright, putting his paws on his hips and staring at us indignantly.

Ann wasn’t blind to the ever-complicating situation and a couple of times even broke down in tears, declaring her notion of finding a new playmate for fraidy-cat Ravi “was all a bad idea.”

Let’s step back just slightly. This story’s title comes from perhaps Eddie’s most distinguishing physical trait, which may also have symbolic value. As you’ll see in the top photograph, he has what Ann admits to being “a ridiculously long tail,” nearly two tails long. It does make you wonder, and I’ve begun to think of Pinocchio and his mythical nose, which would grow longer every time he told a lie. Perhaps Eddie’s tail grows just a tad longer every time he commits a household transgression, which is quite often. After apparently learning his lesson, Pinocchio, the wooden marionette, one day turned into a real boy, his fondest wish. If Eddie the real cat one day turned into a wooden marionette, someone’s fondest wish might come true, and things would be quieter and, um, “safer” around here, with no strings attached.

If one of these days his tail tip begins to grow a satanical spear-blade tip, we’ll know something is, um, following him and maybe us. Should I have honored Poe, not Dickens, in this tail of two black cats? Or perhaps Dr. Seuss, given the scene illustrated below? Taj’s bushy black tail actually had a crooked kink in it. By contrast, my calico cat’s black -and-brown-speckled tail has a lily-white tip, a signifier or not (Of course, Ravi can attest, Chloe has proven no angel in this house).

Understand, poor Ravi was an almost neurotically meek and fearful cat since the first time I met him, although Ann claims he improbably would initiate wrestling matches with Taj. Since his “black bro” has passed, and since Eddie arrived, Ravi has taken on the “clinging cat” role, and to a whole new level – from Taj’s in-Ann’s-face to on-her-head, that is, starting each nap or evening bedtime by laying literally on her head, and often kneading her hair into a rat’s nest, though I suspect Ravi might run away if he saw a small furry marsupial scampering around the house.

Ann prefers not to have her picture taken but, one day, realizing the situation’s ludicrousness, she wryly took a selfie, of her and Ravi (see below). Now she has finally begun to protest to minimize the hair kneading.

“The Cat as a Hat”: Ann (holding back a giggle) and Ravi, in bed. Photo by Ann Peterson

I think these photographs speak for themselves, worth the proverbial thousand words. So, as this little story has exceeded a thousand words already, I need to close. Things are getting a bit better around here, though I know any number of new owners would have by now deemed Eddie as severely violating his parole, and shipped him back to the Humane Society. I’ve never wanted to do that, while biting my lip when “Little Count Dracula” bites Ann’s neck or elsewhere, yet again. She has tearfully admitted she could never return him, despite the household strife. His high zaniness quotient does keep all four of us entertained, each in our ways.

We can only hope, somewhere over the horizon and a lucky rainbow, the worst of times around here come closer to the best of times.

_______________

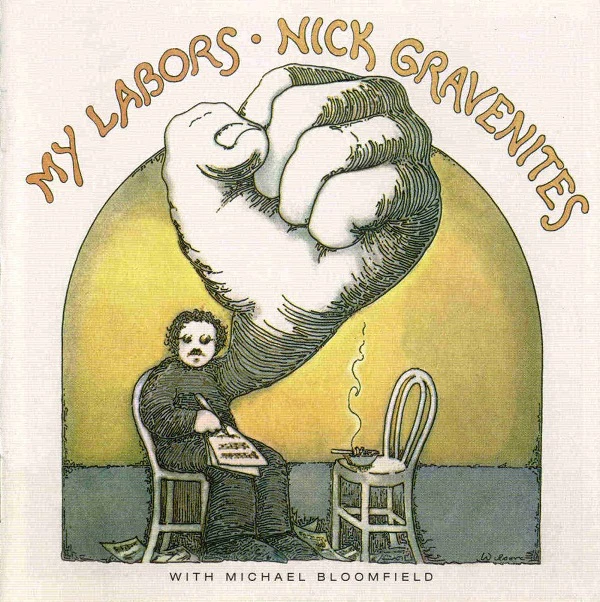

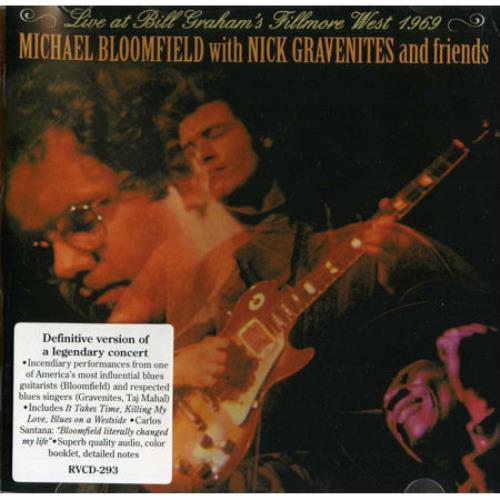

- Culture Note: Despite Ann’s doubts of how much I liked her first two cats, I had been predisposed to do so partly because of their names. Her daughter Teresa had named Ravi after the great Indian sitar player Ravi Shankar who of, course, turned George Harrison and the Beatles onto Indian classical music and its spiritual implications. Shankar also influenced guitarist-composer Mike Bloomfield, who witnessed the sitarist’s Western star-making performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1966, and then wrote the title tune of the Butterfield Blues Band’s profoundly influential second album East-West. Though Ann doesn’t recall the genesis of Taj’s name, I prefer to think that a name-giver in her family really liked the music of Taj Mahal, the marvelously eclectic blues musician.