The strange perceptual disconnect between Vince (Shane Kenyon, left) and his troubled father Tilden (Mark L Montgomery, far right) charges “Buried Child” with contemporary resonance. Vince’s girlfriend Shelly (Arti Ishak, center) and his grandfather Dodge (Larry Yando, background) look on perplexed, for very different reasons. Courtesy The Chicago Sun-Times

Buried Child by Sam Shepard, Writers Theatre, Glenco, IL, running through June 17.

Glencoe, IL – A buried child haunts our times, a ghost that rose in uncanny and shocking ways Friday at Writers Theatre in this northern Chicago suburb. As it played out, Sam Shepard’s reputation-forging play Buried Child had perhaps more stunning resonance than it did in 2001, when the Milwaukee Repertory Theater staged it. Even if you saw it back then, it’s worth revisiting, especially now. It’s a weirdly deft admixture of psycho-drama, quirky horror, dark comedy and culture clash. And it closely peels back the mythology of the heartland. Is that notion rotting away, or only in need of air and sunlight?

Like fearless spiritual homesteaders in dire times, Writers Theatre demonstrated why it has become one of the Chicago area’s premier live theater venues, and it’s only an hour and 15 minute drive from Milwaukee.

What specifically might make such a drive worthwhile? The relevance factor is a hefty reason though it’s far from the only thing. The play felt like an extraordinarily revealing look into the forsaken rural regions of what we might think of as Trump’s America, even if suburban whites actually turned the Electoral College in Trump’s favor. Astute observers now oter that the skewed-to-the-very-rich economics of the 2017 Republican tax cut will deepen the divide drastically further. And with this family’s lack of crops for years, economics is a huge part of the divide in this play as well, echoing Trump’s betrayal of his working-class base, like a sort of narcissistic, weirdly-overfed grim reaper.

This play, which received a Pulitzer Prize in 1979, presages today’s daunting cavern between urban and rural America in both stark and mysterious terms. Even though it premiered in San Francisco’s Magic Theater the year before, and even if Shepard played drums for an East Side New York psychedelic-folk band The Holy Modal Rounders, his play carries only a flashes of baby boomer-type anti-establishment sentiment. Rather, it exemplifies Shepard’s originality and one-step-removed rural sensitivity, and serves as a living, breathing tribute to the playwright and actor, who died last summer of Lou Gehrig’s Disease (ALS) at 73.

Playwright and actor Sam Shepard, who died last summer, exudes a Samuel Beckett-like demeanor in this portrait from 2016. Courtesy The New York Times

Playwright and actor Sam Shepard, who died last summer, exudes a Samuel Beckett-like demeanor in this portrait from 2016. Courtesy The New York Times

Rather than ideology, Shepard once said he found inspiration from a newspaper story about an accidentally exhumed body of a child in a backyard. That became the withering backbone of his play about a mid-eastern Illinois family as diseased as the black, stylized trees on the set appear to be. He charged it partly with his own experience of growing up with a heavy-drinking, mentally-troubled father.

So the play opens with a family patriarch named Dodge staring numbly at a television, hacking convulsively, puffing cigarettes, popping pills, and sneaking shots of whiskey from a fifth stashed underneath the sofa cushion. The first 15 minutes of the play strangely transpire with Dodge enduring his wife Halie’s blathering from an upstairs bedroom. The disjunct symbolism hangs portentously as Dodge clearly subsists in a sort of purgatory, and he’s a pretty good bet for perdition, at any time.

The physical and spiritual disintegration of rural Illinois family patriarch Dodge (Larry Yando) in “Buried Child” is evident in these two sequences from Sam Shepard’s Pulitzer prize-winning play. Courtesy The Writers Theater (top) and The Chicago Reader (above)

Then, today’s miles-deep cultural cleavage between the urban and rural arises when Dodge’s grandson Vince, now a city-dweller, arrives in a surprise visit with his new girlfriend Shelly, after six years absence from family contact.

And yet somehow, he’s become a rank stranger to his kinfolk. Dodge, by turns addled and spitefully pointed, might understandably not recognize Vince. But then, who walks in with an armful of messily-harvested carrots but Vince’s own father Tilden, even more sadly troubled than Dodge, for possessing a conscience. The middle-aged son has fled back home after floundering in New Mexico – and can’t recognize his own son.

This odd perceptual gap lies ripe for interpretation, but today it seems reflective of two very different Americas that seem to perpetually talk past each other and – given this play’s hidden, underlying subject – it evokes the somber saying, “We hardly knew ya.”

The harvested crops also carry peculiar weight. Tilden had previously hauled in an overflowing armful of corn, to the disbelief of both Dodge and Halie, who insist that their back lot hasn’t spawned corn for 30 years. In a stunning scene that closes the first act, Tilden delicately covers his father, now asleep on the sofa, with all the corn husks he’d just shucked. It’s a burial of sorts, slightly ghoulish and golden, but also richly resonant in its visual and organic presence.

Bradley (Timothy Edward Kane), one of family patriarch Dodge’s sons, comes home to discover his sleeping father buried in freshly-shucked corn husks, in Writers Theatre production of “Buried Child.” Courtesy Theater Mania

The urban couple’s arrival signal’s Shepard’s early feminist instincts, as Shelly stakes her ground and identity, and earns grudging respect from the country folk. “She’s a pistol, isn’t she?” Dodge exclaims. Shelly also stands as the fulcrum of relative sanity in the goings-on, especially after her boyfriend comes home raging drunk, seeming just as much of a lost cause as the other family’s males.

Mother Halie (Shannon Cochran) is a case, in her own way, cloaking the family’s secret in bourgeois normalcy, while ever on the edge. She’s also carrying on a barely-concealed affair with a local priest who, despite his counseling background, is utterly lost at sea amid this family’s swirling currents of craziness.

As for the source of the madness, that could be a complexity of factors, but perhaps the deepest of all lies somewhere out in the back, as mysteriously present as the sudden crop harvest. Old man Dodge carries his burden like a shipwrecked Ahab floating back to the surface, with no purpose left, only spite, bile, and self-made doom. Larry Yando manages to reveal some bleakly comical aspects to this character’s roughly-carved visage.

Indeed, the play seems hell-bent on sweeping, in slow-motion, down into an engulfing whirlpool. Then comes the ending, where Shepard brilliantly cuts in several different directions, lending the play a weird suspension, and his finest lines of the script. We hear Vince, in a nightmarish recollection of his intended flight thwarted by ghosts; and then Halie up in her oddly elevated bedroom again, exclaiming, suddenly entranced by the sun-blessed crops she sees for the first time. Her unpretentious aria entwines gritty lyricism and blind pathos:

Dodge? Is that you Dodge? Tilden was right about the corn…It’s all hidden. It’s all unseen. you just gotta wait till it pops up out of the ground. Tiny little shoot. Tiny little white shoot. All hairy and fragile. Strong though. Strong enough to break the earth even. It’s a miracle, Dodge. I’ve never seen a crop like this in my whole life.

Maybe it’s the sun. Maybe that’s it. Maybe it’s the sun.

Her clipped, building phrases, reflecting Shepard’s drummer’s rhythmic sense –and his skill with chilling metaphoric analogies – carries potential redemption of the heartland myth. And yet, the long, grim shadow looming over this family will crisscross Halie, and her revelation.

____________

For tickets and other information on WT’s Buried Child, visit: Buried Child

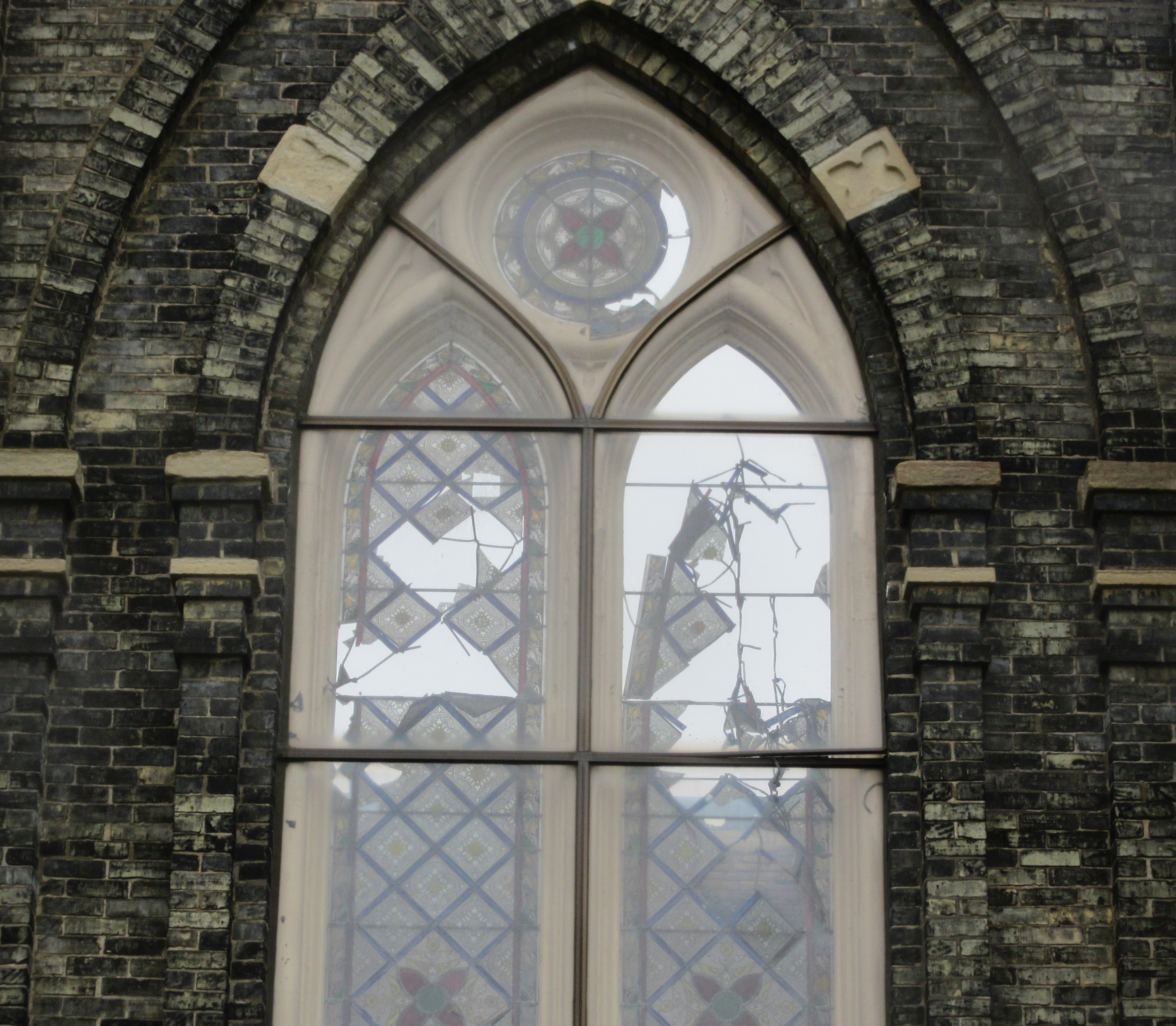

I was especially disheartened by the news of the terrible fire that ravaged Trinity Lutheran Evangelical Church in downtown Milwaukee recently. While walking back to my car after participating in the March for our Lives event on March 24, I passed the church and its beauty and deeply aging majesty captivated me. The cream city brick is especially evident as an ornamental offset to the darker brick, lending the structure a distinctly Milwaukee character.

I was especially disheartened by the news of the terrible fire that ravaged Trinity Lutheran Evangelical Church in downtown Milwaukee recently. While walking back to my car after participating in the March for our Lives event on March 24, I passed the church and its beauty and deeply aging majesty captivated me. The cream city brick is especially evident as an ornamental offset to the darker brick, lending the structure a distinctly Milwaukee character.