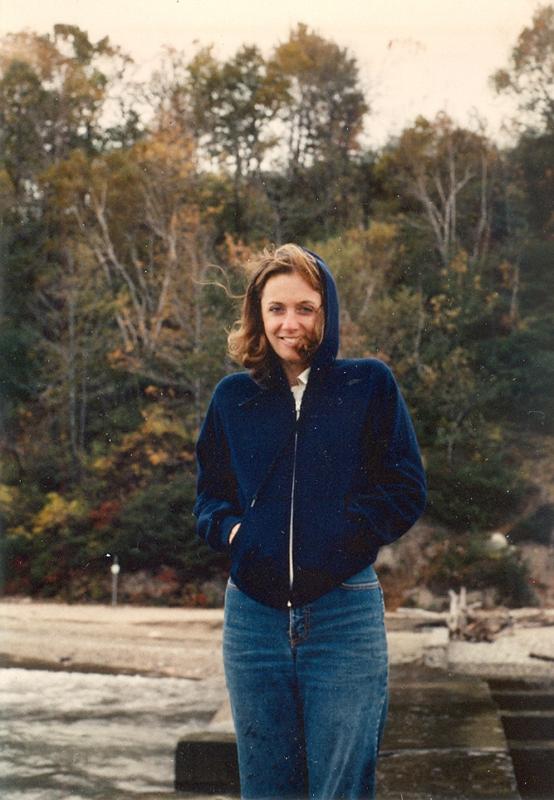

Kathleen A. Naab (June 22, 1953-September 20, 1999) Photo by Kevin Lynch

Blogger’s note: This is the most personal blog (and perhaps the longest) I have written to date, but there is a reason. Yes, Kathy Naab was my first spouse, and she died tragically in 1999, after our marriage ended. And there’s certainly personal perspective, but I post this on her birthday because her story is little-known: She was a cultural person and a significant contributor to Milwaukee’s culture as an entertainment columnist and movie expert. She was also a fairly remarkable person. (Posted June 22 at 8:53 p.m. CST)

I could write a preface on how we met/ so the world could never forget…Then the world discovers as my book ends/ how to make two lovers of friends. — Lorenz Hart, from “I Could Write a Book.”

The moment I first saw the woman who would become my wife was peculiar– the opening salvo of a tiny turf war. I had walked away from the desk that The Milwaukee Journal features editor Don Dornbrook had just assigned me, as a now-regular freelance contributor to his department.

In retrospect, the moment is a measure of the respect that this woman never achieved at The Journal, even as a full-time staffer: Kathy can share her desk with a freelancer, no problemo.

A decade later, leaving the paper would precipitate her decline.

I’m getting ahead of myself. I was standing a few few feet away from the desk, and I heard a sound and turned around to see a bespectacled young woman with her palms slapping down several times on the desk. She eyed me with a trace of quirk, almost like a chimp vying for attention. I soon learned it was turf instinct.

“Um, this is my desk,” she said, in her throaty voice, almost swallowing the words. Something in that voice disarmed me.

“Oh, your desk?” is an approximation of my ringing retort. “Oh, excuse me. There must be a mistake or…” We negotiated a bit of shared space and time, exchanging each other’s schedule information.

Actually, I wasn’t really attracted to her right away. At the time, she was quite thin, 5’6” and maybe 97 pounds, with large glasses that accentuated the leanness of her face. In fact, she had the high cheekbones of a beauty, something it took me a while to really notice, partly because of her dazzlingly big peepers.

But her clothes downplayed her looks, almost always a virtual uniform of somewhat baggy brown pants and penny loafers topped by a red-and-brown plaid blouse . She would often sit at her computer terminal with her legs folded over yoga-style. She clacked away at a secretarial speed.

Still, my initial response was shyness perhaps because I was a rookie Journal freelancer and this was actually a pretty woman with a lively and tart sense of humor. And she was a journalist. She started to grow on me, and was very helpful, showing me the ropes of paper, and negotiating the ins-and-outs of the computer system. And she was a font of quick information on many matters entertaining.

I finally got around to asking her out to dinner and a flick because this woman was a movie aficionado. But all I remember is the very end, when I was about to leave her house. I followed her to the door and she turned around and I sort of had her cornered. I decided to move in, for our first kiss. I closed my eyes and planted a fat, wet one — almost on the doorway screen. Surely a demure fly waited on other side for my hungry lips. The question is, who was hungrier, the insect or the guy?

Almost staggering, I opened my eyes.

No Kathy.

I peered down. There she was, sitting at my feet, on her haunches, her green eyes peeking back at me. Our first kiss had suddenly devolved into a guerrilla-warfare tactical blunder.

“Uh, sorry. Ah dunno, it’s been a while, y’ know,” she said.

“Gee, what made ya do that?” I blurted. But she was too embarrassed to come up with the response I’d have preferred, like “Oh, you really made me weak in the knees.” She slowly stood up and I awkwardly found my labial target.

***

Life with Kathy was, among other things, a movie-trivia game par excellence. She was a feature writer, copy editor and wrote a popular entertainment question and answer column for the Journal feature section called You Asked.

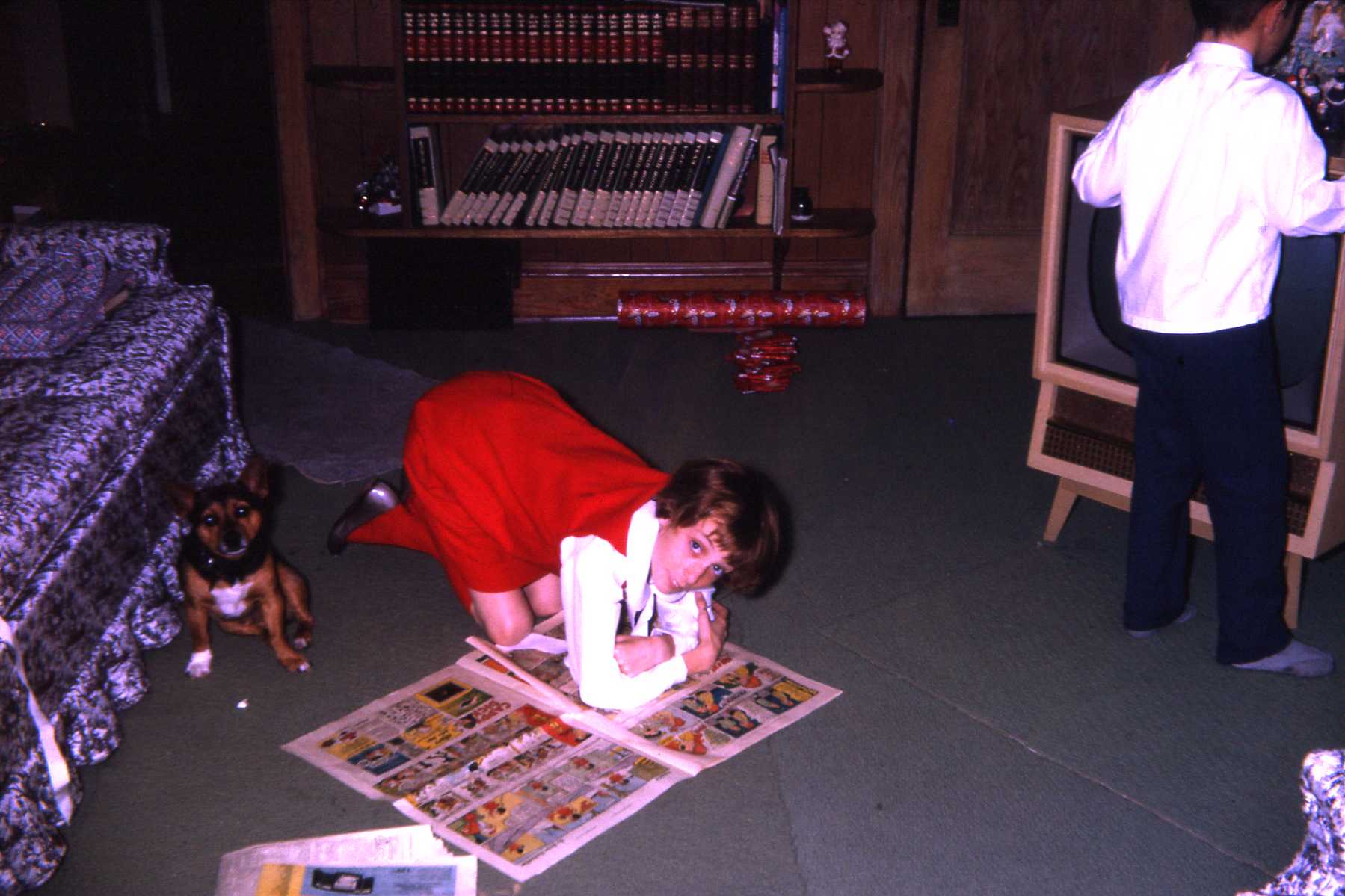

Kathy Naab doing some early entertainment “research” that foreshadowed her years as a columnist for The Milwaukee Journal features section.

In retrospect, the simple selflessness of the column title, a step removed from a servant response, reflected what I would come to understand as her confoundingly low self-esteem. I felt the actual journalist doing the column called for a more clever moniker, which she was fully capable of.

And yet, I would come to understand her critical sensibility was strong, largely influenced by Pauline Kael, the storied New Yorker film critic who was one of the first to come to terms with addressing middle-to-lowbrow movies that had redeeming value as popular culture. Kathy had well-thumbed copies of all of Kael’s severalvolumes of collected reviews and features centered over our shared desk, along with a small raft of books on entertainment and especially film, such as Halliwell’s Film Guide, Roger Ebert’s very first review collections, and David Thomson’s erudite and often arguable Biographical Dictionary of Film.

Kate Naab (right) was intellectually curious yet unpretentious.

This was all pre-Internet, of course. That’s a big part of why her column was so successful. People still relied on print journalists for information and she provided knowledgeable, bright and witty responses.

Although she appreciated some highbrow music and liked jazz well enough, she loved cultural slumming, with an acute sense of camp. One of her favorite refrains was “It was so bad it was good.”

A punky adolescent Kathy giving a “beach bully” a raspberry.

So she really was fun and easy on the eyes. When she doffed her specs, her deftly made-up orbs and auburn hair – often a stylistic experiment — coalesced with her fine-boned features.

And over the next few years she started to put on a few pounds which was nothing but good on her. I’d like to think her comparative health had to do with the growing happiness of our relationship, but I don’t know.

Most the time, she was perky and sweet, leavened with several shades of snark. Yet she could fall into funks as if she were physically imploding, and sequester herself in her bedroom room for several days, recalls former roommate Annette Gelhar. And she could always out-drink me, like a Frank Lloyd Wright waterfall cascading into the kitchen. At the time, I knew virtually nothing about clinical depression, or alcoholism. In fact, in the 1980s medicine still had a paltry grip on what turned out to be a bipolar condition.

So the ups and downs gradually began to get me in a slo-mo tizzy. We decided to take a break from dating. I met a stylish, artsy older woman, a painter, and started seeing her.

When Kathy found out, she took a nosedive. A friend of hers finally informed me some weeks later, and we had a talk and ended up getting back together. I think this is when she started putting on a bit of weight. She turned into a fairly alluring woman because she had that almost comical, irreverent personality and keen, pomposity-piercing intelligence.

I never realized she had spent six months in the hospital for anorexia, in her adolescence. She’d always kept that from me. Her younger sister Kris Verdin shared that fact with me recently. The obsessiveness of anorexia may have been an early manifestation of bipolar tendencies, Kris and I both now suspect. Kathy herself said she had “mother issues,” but who’s to say how that played out.

***

I felt my affection growing for the once-geeky chimp girl I’d first met. I’ll fast forward through the marriage and some good times, for efficiency. But I’ll say we made a great match — when was she feeling good. We virtually never argued, either.

One delightful trip out east involved me doing an interview in Brooklyn with jazz pianist Cecil Taylor for a Down Beat profile. We also visited Franklin Roosevelt’s home in Hyde Park, and Bruce Springsteen’s Asbury Park, went upstate New York and hit Cooperstown, the Baseball Hall of Fame, taking our turns in the batting cage with a mechanical pitcher.

A madcap parking-detour trip through what seemed like Milwaukee’s near south side had gotten us to the Brewers’ pennant-winning game in 1982. And then, dashing down to grab a hunk of the dirt from under walk-off game-winner Cecil Cooper’s masterful batting stance felt like a Hall of Fame thrill we shared with Kate’s West Bend high-school pal Ann Rosso.

Also on the New York trip, like countless others, we went to the top of ill-fated twin towers of the World Trade Center. The picture of her up there touches on a token of the paradox of her self-esteem. She was a hearty down-hill skiier. Also, notice the wonderful family photo of her (below) as an adolescent with her three siblings, Bryan, Kris and Steve. She’s momentarily the only one brave enough to peek over the edge of the Olympic-height ski jump they’re clambering on during the summertime.

Kathy atop the World Trade Center in 1986. Photo by Kevin Lynch

In 1989 I finally got a full-time job at The Capital Times in Madison. Kathy was struggling mightily with her un-diagnosed bipolar condition and her drinking. It was tough enough for us to have waited this long for some financial security. We had postponed beginning a family and she was grappling with the idea of moving to Madison.

“Kathy always had a hard time with change,” her sister Kris says. We agreed I would move by myself to start my job as an arts reporter, and she managed to make it six months later.

But those six months entrapped her like the web of a black widow spider. She lost her job, I think due to absenteeism from increased drinking and depression. That isolated her in the Milwaukee flat I’d left her in. I slowly came to realize that her life had grown unmanageable, to use the AA euphemism.

***

Our “new-and-improved” life was too much of a step for her to take. That’s how much this illness and alcohol can screw up a person’s perspective. At the time, bipolar manic depression still seemed poorly understood even by medical pros and, frankly, very few of the medical people whom I encountered did her much good.

One day I walked into the hallway leading to the bedroom and she emerged very drunk. She retched on the white runner rug. Then she staggered to the kitchen and pulled out a sharp knife and waved it groggily over her left wrist.

I grabbed the knife and quickly got her to a fairly new nearby Madison mental health facility. The main thing they did was give her shock treatments. The facility didn’t last long. And to my own shock, that crude and ugly technique would also be the last strategy tried on her repeatedly before her death ten years later, courtesy of the world-acclaimed Mayo Clinic. To me, the medical system has the most tenuous grip on many mental health issues, certainly bipolar condition exacerbated by alcoholism.

After another sad suicidal gesture in Madison, her father Henry and I took her to the Milwaukee Psychiatric Hospital, where she lived, in and out of rehab, for over a year, while I lived and worked in Madison.

I realize I may see a different Kathy in the mists of memory. She never really got with the AA program. She’d work at it, eventually relapse, rehab and, I’m told, struggled with “honesty” as a recovery program issue. Our joint credit card account began bulging with cigarette, medication and “spirits” charges. One friend says she treated me poorly — and she did at times, but I might have neglected her in those too-many months apart, even though therapists and Al-Anon counselled me, for my health, to “detach from my co-dependency.” During the short time she lived in Madison, I had begun facilitating her “jonesing” for alcohol, which I hated doing.

But today, oddly enough I don’t remember much of that as painful, even though it really started to feel crazy for me. The walls sometimes began to close in, at odd angles, with her unpredictability. Kathy was often high maintenance, but not in the sense of a demanding shrew. For as much as she may have asked of me unintentionally, I remember her plaintively asking more often, “D’ya still like me?” even well into the marriage.

She never turned her insecurities into petty domestic tyranny. In the only video of her I know of, we are hosting Easter dinner and as she prepares an excellent dinner. She repeatedly asks me to set a smaller card table for the overflow of people and I — too busy entertaining my family — repeatedly fail to respond. She never gets irritated, as perhaps she should have. She’s having too much fun hosting, and she charms the camera man, my slightly lecherous brother-in-law, without even trying. She had a sort of mania for life, which could be infectious, but which also knocked her down to the mat, time and again.

Kathy, the hostess with the mostest, at least cooking accoutrements.

That see-saw played cruelly with our relationship, especially in those fraught nine months or so we spent together in Madison.

***

On the last phone call I had with her a few months before her death, Kathy told me of a harrowing experience at the Mayo Clinic and their shock “therapy.” My brain is so fried that all I can do is read mystery stories,” she moaned.

She had been an English major and she wrote a thesis paper on the ultra-literate Henry James. And she was a seasoned and gifted journalist and writer, with a bright and sassy wit to her style. Kathy Naab aspired to be a movie critic and was a true movie expert, which manifested itself in her deeply knowing and researched “You Asked” column. She scorned nationally syndicated entertainment columnist Jay Bobbin for his consistently easy entertainment Q and As.

Having absorbed the writing of Pauline Kael, she found an intellectual role model in the sometimes acerbic and eccentrically brilliant New Yorker critic.They both shared a general disdain for pomposity and an appreciation of both high art’s Jamesian nuances and its snootiness, and that a lot of “trashy” movies can contain their own peculiar redemption, for your apparent time wasted on them.

Kate’s catchphrase “It was so bad it was good” was in a sense, a kind of hip-pocket aesthetic motto. A person who studied James and appreciated Miles Davis easily rode the ski lift from low to high culture without getting stuck in snobbery. She also loved the big-hearted and cornball sentiment of many musicals, reflecting her experience as a piano accompanist for her high school stage productions. She relished sitting down at a piano and, in her creaky singing voice, plunking out her favorite song, Rogers and Hart’s “I Could Write a Book.” This was Kathy in her element. 1

Kathy with her grandmother Eunice Klumb, part of a musical family. Photo by Kevin Lynch

But she only got one chance to actually review a movie at The Milwaukee Journal in all those years as a full-time staffer who knew as much about movies, if not more, than anyone actually reviewing them. The movie was Ishtar, the 1987 Warren Beatty-Dustin Hoffman revival of the Bob Hope-Bing Crosby buddy movie trope. Most critics sneered at it, but Kathy drew appreciation with a sharp critical aim, like a full-quivered archer. She called it a cinematically rich but over-budgeted screwball comedy-adventure, commenting, “Der Bingle isn’t rising from his grave but he may be spinning in it – and chuckling.” She deftly calls out the established female director for under-serving her female characters: “Setups for some Hope-Crosby-style sparring over (Isabella) Adjani’s affection start to simmer. But writer-director (Elaine) May is merely blowing bubbles. In the end, the talented Adjani has served little more progress than a prop. (Carol Kane and Tess Harper, talented actresses as well, are employed similarly and exit swiftly opening scenes in New York.).”

Kathy also ambushes any politically-correct complaints about Arab characterizations: “Ishtar is foremost a character comedy, next a cloak-and-dagger spoof. But it takes side roads into political satire and culture-clash humor, and they’re wittily, tastefully and incisively done. The Arabs aren’t the boobs; rather Hawk and Lyle (Hoffman and Beatty) are after they don Valentino-style chic garb to elude the CIA operatives.”

But judge for yourself. Here’s Kate’s entire Ishtar review in a newspaper PDF, with a jump to page 4B:http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19870515&id=PV0aAAAAIBAJ&sjid=iioEAAAAIBAJ&pg=2066,6481152

“What a talent!” is how Kathy was succinctly remembered by Jackie Loohauis-Bennett, another very gifted entertainment and feature writer for The Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel who died too young herself.* Kate’s talent was pigeonholed and clearly underused at The Journal. That situation never did much for her self-esteem, which I’m sure now is a big part of what fed into her cliff plunges into darkness.

Jackie recalled the whole Entertainment Department fell into a quiet hush when I telephoned Kathy’s friend, entertainment writer Tina Maples, with the news of her death on September 20, 1999.

“She was an amazing, blazing intellect, and hilarious, too,” recalls Maples.

Kathy could “blow bubbles” with her nephew Danny, but not like writer-director Elaine May in “Ishtar.” (see above)

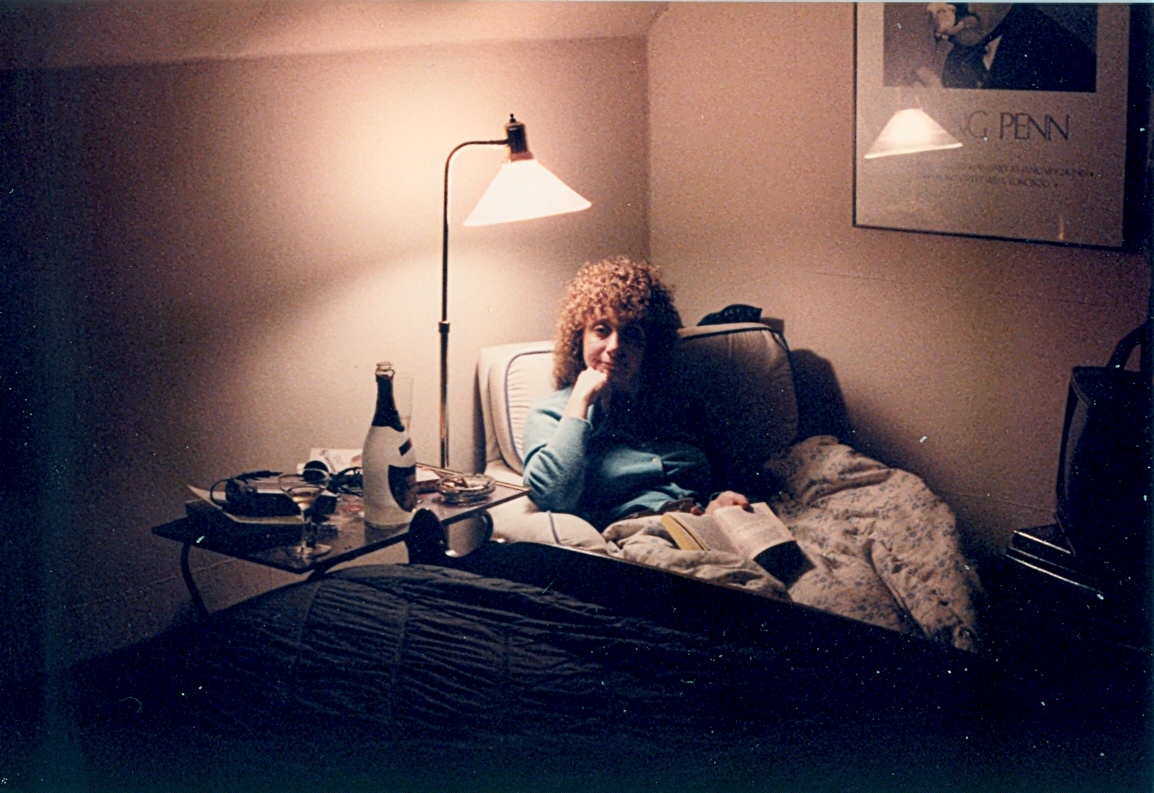

I’ll admit that I didn’t have enough understanding of what was going on with her then. In her fateful six months in Milwaukee, after I had started my job in Madison, her drink of choice had become champagne. I suspect she felt it was the one booze with an upper, that gave her a boost to her happily “higher self.”

Kathy in her bedroom (shortly before I got a job in Madison in 1989) with Irving Penn’s famous portrait of Woody Allen disguised as Charlie Chaplin’s “little tramp.” Photo by Kevin Lynch

Kathy in her bedroom (shortly before I got a job in Madison in 1989) with Irving Penn’s famous portrait of Woody Allen disguised as Charlie Chaplin’s “little tramp.” Photo by Kevin Lynch

When we divorced it was her choice, but it felt painfully like all for the best. I didn’t realize what this would lead to, for her.

***

At some point, she had fallen for another Milwaukee Psych patient, a smooth-talking but disbarred pediatric neurologist, also with a drinking problem, from what I’ve heard. Finally, she went AWOL with her new lover. When she called to tell me she was in Green Bay with the guy, the news affected me in a surprising way. Oddly, I didn’t get angry or upset. Instead, I felt overwhelmingly dumbfounded.

I went speechless, as if catatonic, for the next few days. It may have been a byproduct of the loss-of-speech-faculties that I occasionally suffer as a symptom of epilepsy. I improbably ended up briefly in Milwaukee Psychiatric Hospital — with my still-AWOL wife at the same time, a very bizarre circumstance. When she got back from her romp with the ex-doc, Kathy came to my room and said, “Kevin, I never wanted to hurt you.”

Lame as that sounds, I truly believed her. I could say nothing in response at that time. In retrospect, it seemed a perfect summation of the relationship gulf we’d arrived at. That’s something else the sickness had created, like the devil doing his dirty work, day after day after day, for God knows how long.

Kathy eventually rented a farm house outside of Elroy, Wisconsin with her boyfriend. A few years later, on a fall colors driving trip to Minneapolis, I stopped and visited her. She seemed somewhat happy then. Living out in the country, with a motley menagerie of cats and dogs she’d adopted, was something she always dreamed of.

Young Kathy Naab holds Keetzer the kat, in the backyard of her family home on Western Avenue in West Bend.

But as AA preaches, alcoholics isolating together is often deadly, especially for the most vulnerable of the two.

After she moved there, her older brother Steve, who lives in Lodi, says he entertained thoughts of going to Elroy and “kidnapping her.” On my visit, I stayed there overnight. Her housemate Craig happened to be gone, probably back in rehab. He called, but she didn’t tell him I was there. When she went to bed, we had a moment that recalls for me the end of the classic screwball comedy The Awful Truth, with Cary Grant and Irene Dunne. It’s about a divorced couple who one night end up sleeping in the same cabin together, in different rooms. Like Cary, I had a long pregnant pause at the doorway of her bedroom, as she lay in bed and we bid each other good night. Then she gave me a long look. I’ll bet she thought of The Awful Truth, but perhaps any number of other things.

It did not end, as the movie ends, happily ever after. Had I more courage, had I known… That visit was the last time I saw her. In September of 1999, she died of an apparent drug/alcohol overdose in that same farmhouse, alone. Not long before, she had said to her mother May over the phone, “I’m 47 years old, mom, who would want me?”

What was she was thinking that last dark night of the soul?

“September, November, and these few precious days…”

Her father Henry, distraught at her wake, said simply, “What happened?”

She taught me things of value, including the idea that “it’s so bad its good” isn’t a critical cop-out. It’s a mental spade for digging up the good in even flawed cultural attempts (how many are perfect?), even though I still reflexively suspect many big commercial successes.

But most especially she taught me this: Kathy loved me first, I think, but never forced herself on me. We were “dating pals” until one day I realized what I had, right in front of me. She knew how to “make two lovers of friends.”

Lover and friend. She’ll always be both, in the part of my heart with the small crack in it.

_______

*Award winning Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel writer Jackie Loohauis-Bennett died tragically at age 62, from heart failure after coronary surgery in July, 2013.

1 Maybe Kathy was onto something with musicals. There’s a new book out called Dangerous Rhythm: Why Musicals Matter. Partly they matter for their universality, because they easily traverse virtually all story genres, they “contain multitudes,” as a Whitmanesque reviewer recently wrote. Maybe Kathy also felt her exuberant “I could write a book” highs in their delirious production numbers, and her lows in their often-sappy depths. And yet the great musicals accomplish so much. For example, aside from their at-times- transcendent music, the glorious My Fair Lady arguably did more to raise consciousness about class differences, bias and challenges than any other film. And West Side Story brought us deeply into the gang world, then virtually invisible, that would become a pervasive part of contemporary subculture, profoundly impacting mainstream culture. In tackling issues of race, few productions or films ever did so with more indelible style, insight and soul than Porgy and Bess and Showboat.

Unless otherwise noted, all photos by Henry Naab, courtesy of Steve Naab.

Special thanks to Steve Naab and to Kris Naab Verdin.

A tugboat pulls the Charles W. Morgan out to sea for a rare historical informational festival tour about whaling along the eastern seaboard.

A tugboat pulls the Charles W. Morgan out to sea for a rare historical informational festival tour about whaling along the eastern seaboard.