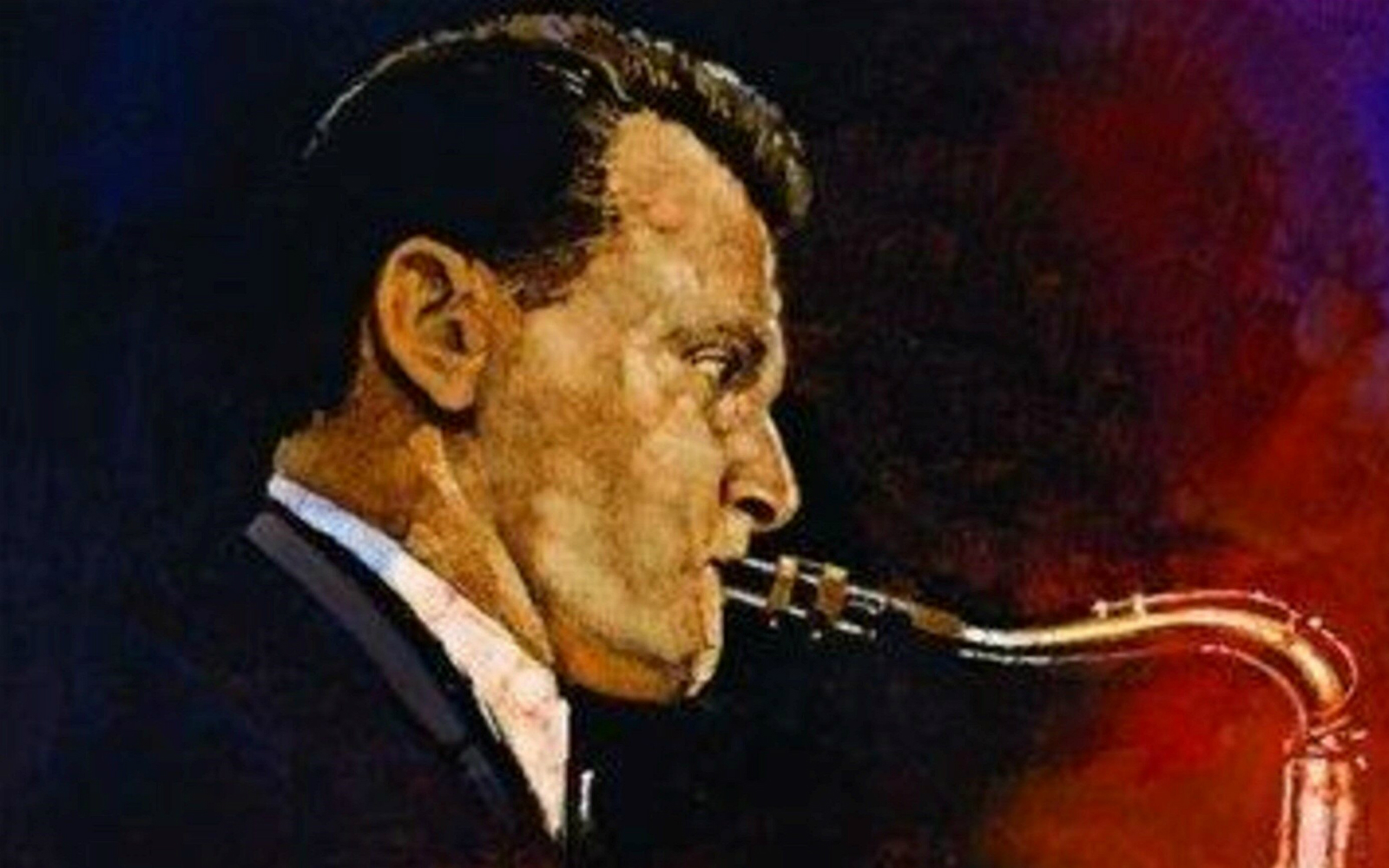

A portrait of Stan Getz. Courtesy RW Theaters.

Why now? Why Stan Getz now? Because he’s a voice in time and beyond time, a voice within and wherever. Wherever I go, I’ve come to know, I yearn to hear him, and all he has to say.

I understand now, as well as a non-saxophonist can, what John Coltrane meant when he said of Getz, “We’d all sound like that if we could.” Coltrane was, among other things, a supreme master of balladeering, where many saxophonists make their bid for a sound as beautiful as possible.

My own analogue to Coltrane’s indirect superlative: I would carry Getz’s sound with me further than any other instrument’s, if forced to forsake all but one. Maybe it’s a Sophie’s choice between Getz and Miles Davis.

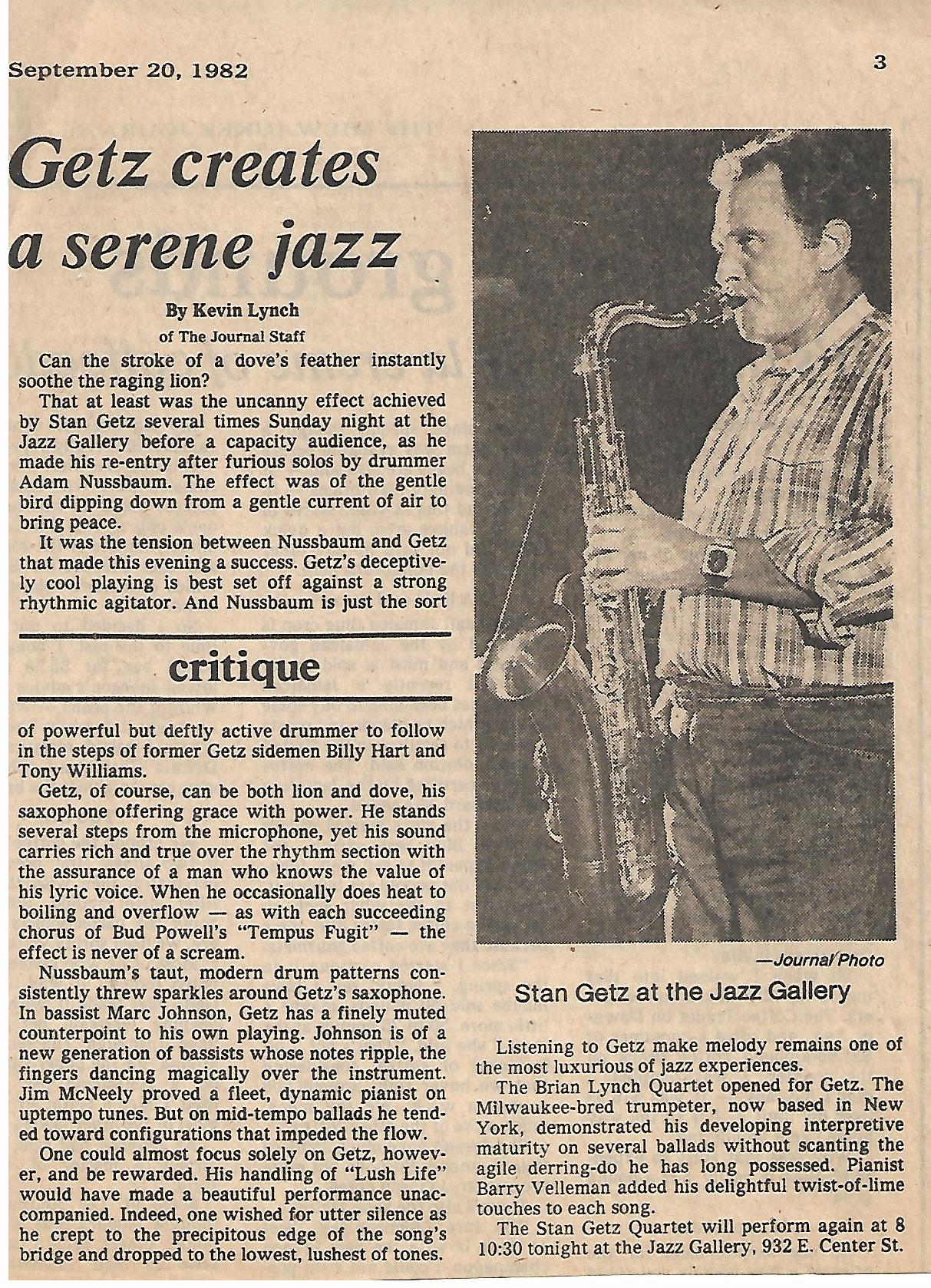

As a relatively young journalist, I had already reviewed a Getz performance at the Milwaukee Jazz Gallery for The Milwaukee Journal, a highlight among many superb artists I heard and reviewed there. Two years later, I interviewed him in Chicago, then wrote a feature previewing a Getz performance at a Rainbow Summer concert in Milwaukee. There I met him again afterwards and, though brief, the reacquaintance still holds a tight grip on my heart. You see, after a brief exchange of pleasantries, I agreed to accompany him in a walk to his hotel room, but he had one small condition.

Would I please carry his saxophone for him? After the performance, he was fatigued, partly the byproduct of years of abuse of his body with drugs and alcohol.

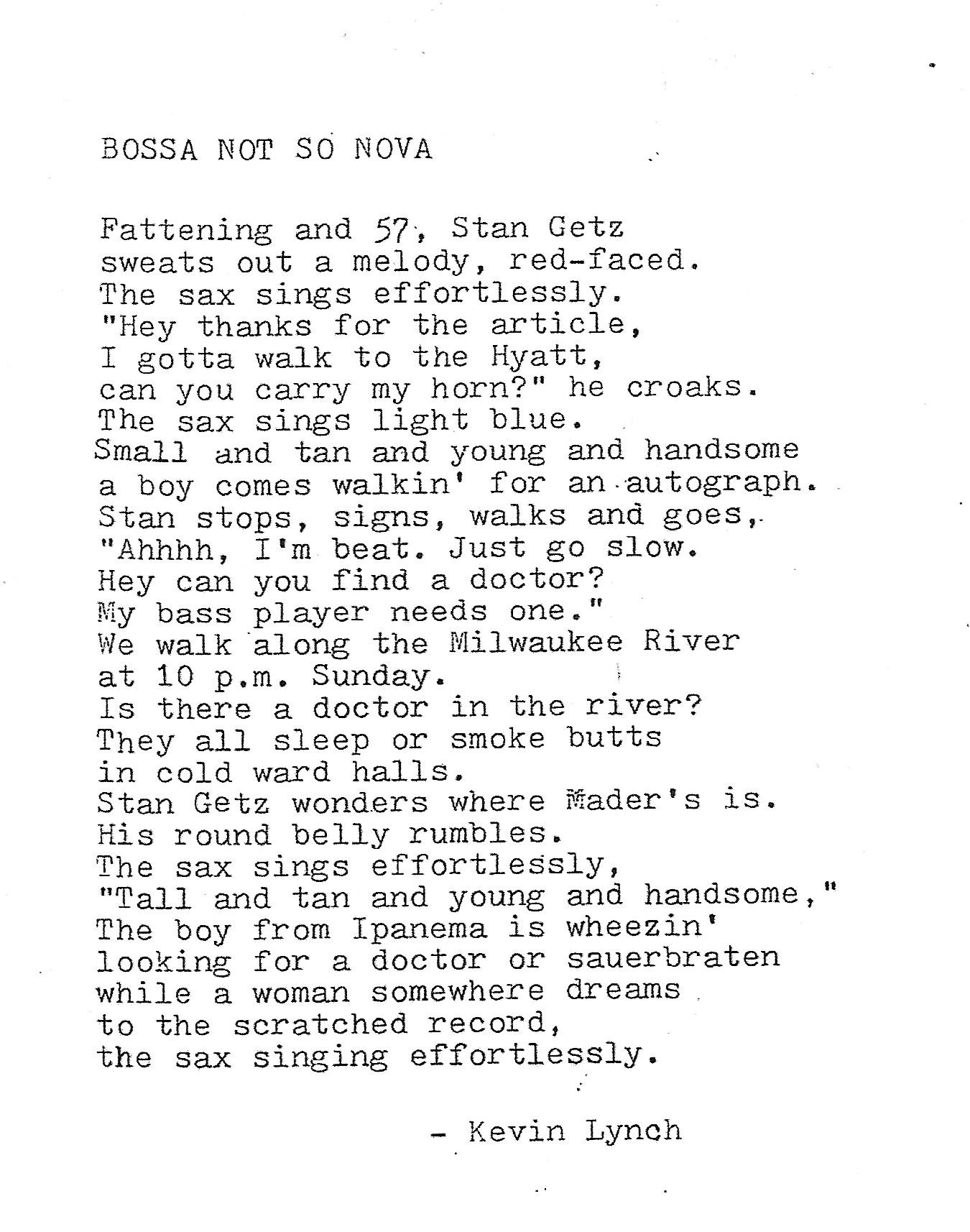

I accepted the task gladly, and the instant thrill of carrying one of the world’s most revered artistic instruments, beside its owner and artmaker, inspired a short poem, “Bossa Not So Nova.” 1

So, I’ve written about Getz in three modes but, mea culpa, it still doesn’t seem enough.

Lately I’ve revisited him upon buying a used copy of the Getz musical biography Nobody Else But Me, by Dave Gelly. It discourses across the artist’s career with close readings of numerous Getz recordings, his legacy beyond memories, as he died in 1991.

This excellent book prompted me to dig out an array of Getz recordings.

As I write, I’m listening to him essay “Infant Eyes,” an exquisite ballad by another giant of the tenor sax, Wayne Shorter, and each limpid whole note unfurls with delicious tenderness and knowing delicacy.

The album “Moments in Time,” recorded in 1976, was released in 2016. Courtesy Resonance Records.

But he’s much more than a fatherly cradle-rocker.

I couldn’t have responded to this recording much earlier than a few years ago, when I obtained a copy of the Getz album Moments in Time, recorded live by Getz’s Quartet in 1976, but not released until 2016 on Resonance, a label specializing in what I’d call “jazz archeology.” 2

And there’s more affinity between Getz and Shorter than a few of Wayne’s tunes in Getz’s repertoire. The sound of their voices resonates similarly, an exquisitely soft vibration, a singing like a distinctly masculine bird that — warbles and vibratos aside — can hold a note like a distant horizon of destiny. Both saxophonists have lived lives deeply shadowed by tragedy, likely informing their profound sensibilities.

Indeed now, the tune playing is “The Cry of the Wild Goose,” by trumpeter Kenny Wheeler, and it belies one misplaced reservation I held about Getz in the past.

He disabused me of it when I saw him in 1982 at the Jazz Gallery.

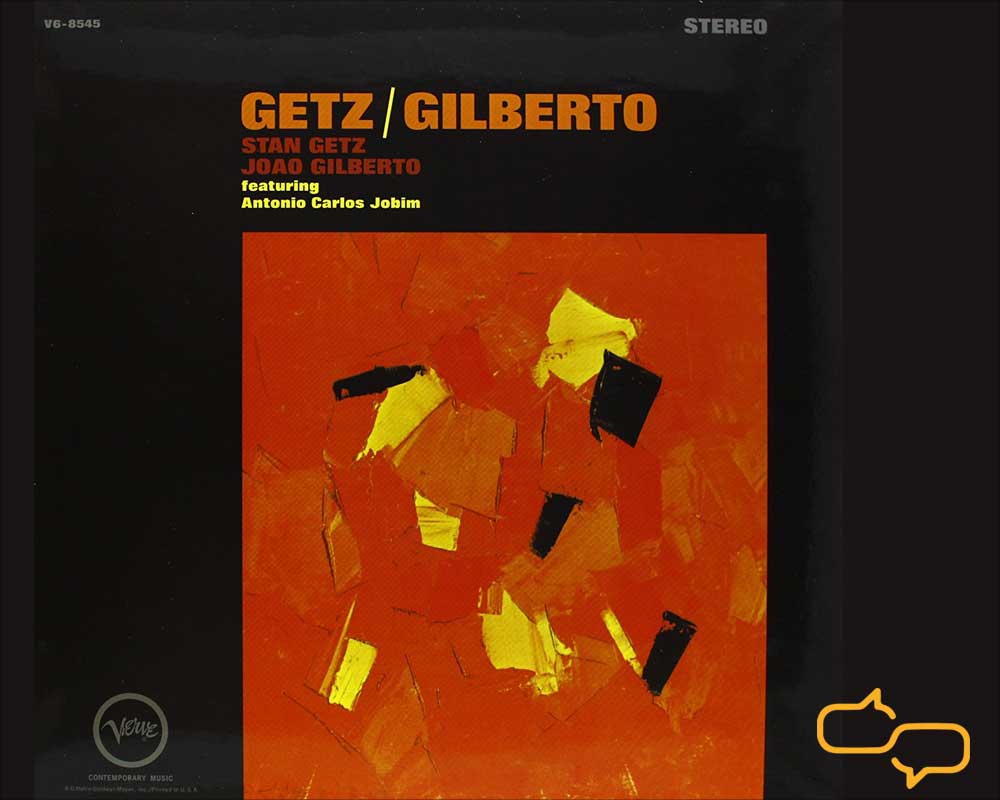

But I’m referring to back in the mid-1960s, when he broke into broad public awareness with his lilting bossa nova luminosities. He could hold and caress a note as if it were palpable and breathing which, with him, it truly was. Such audible tenderness enchanted me as much as any other single jazz artist did with one recording, Getz/Gilberto.

Cover of the famous album “Getz/Gilberto.” Connect Brazil.

And sure enough, right now with Horace Silver’s “Peace” (from Moments in Time), Getz is beguiling yet again. Getz/Gilberto, created, arranged, and recorded by virtually all Brazilian musicians, racked up unprecedented sales for a jazz recording (2 million copies in 1964) and became the first non-American album to win a Grammy Award for Album of the Year, in 1965.

But back during the bossa nova craze, for all my admiration, I doubted whether Getz was capable of anything approaching what I call “The Cry.”

I do hear a cry in the “wild goose cry” tune I’d just heard, but I’m referring to a sound often heard among saxophonists in the 1960s, during the same time Getz lulled and seduced with “The Girl from Ipanema.”

Getz and vocalist Astrud Gilberto who sang the huge international hit, “The Girl from Ipanema.” which propelled the album “Getz/Gilberto” to great sales heights and an “Album of the Year” Grammy.

The notion of “The Cry” is the expressionism that numerous saxophonists especially began manifesting during that period of social upheaval and raised consciousness over racial injustice. It’s a heavily freighted topic and subtext. So perhaps its unsurprising that a naturally lyrical white saxophonist isn’t easily associated with it. Nevertheless, over the years, the true and extraordinary range of Getz’s expressive power expanded, and his own version of “The Cry” arose, as such a vivid contrast to his inherently singing style that it carried the weight of striking effects, like a sculptor’s chisel discharging chards and sparks, to convey how life can force us to extremes of feeling and response.

To me, Getz seemed to be universalizing the plight and poignance conveyed in “The Cry,” most often associated with African-American musicians. This is not to minimize the racial suffering those artists endured and expressed, but to find the shared humanity in it. Getz’s suffering might be arguably his own demons’ making, more than of a cruel society built on systemic racism. He even was capable of violence under the influence, which he always regretted, even serving brief incarceration.

Gelly insightfully notes a great irony, how the drugs and liquor might’ve facilitated an “alpha state” in which, Getz explained, “the less you concentrate the better. The best way to create is to get in the alpha state…what we would call relaxed concentration.”

Such can be the price of art. Does that make it ill-begotten? Illegitimate?

As a Russian Jew, he may have had ancestral instincts of suffering and class oppression hounding his psyche. Accordingly, he seems a different sort of expressive animal — “Nobody Else But Me” as he might say. The simplicity of the declaration also may reflect Getz’s uniqueness, his fingerprint identity, his sonic originality as a pied piper whom, when heard, we still feel compelled to follow, decades after bossa nova first sailed across waves and valleys. Years after his last living breath.

Thank the music gods for his voice, retrieved and captured.

_________

1 a poem about Stan Getz (written to the cadence of “Girl from Ipanema.”)

2 Moments in Time comprises mainly classic and modern jazz standards with Getz’s working quartet at the time: pianist Joanne Brackeen, bassist Clint Houston and drummer Billy Hart. However, Resonance also released simultaneously a Getz album Getz/Gilberto ’76, highlighting guitarist-singer Joao Gilberto, and Brazilian songs,

pps. I also wrote about Getz when I found a used copy of his album Sweet Rain, as few years ago.

3. Here’s a review of a live Getz performance at The Milwaukee Jazz Gallery, in 1982: