A Southerly Cultural Journal, Vol. 4

Appalachian Mountains courtesy: http://www.conservapedia.com/Appalachian_Mountains

Appalachian Mountains courtesy: http://www.conservapedia.com/Appalachian_Mountains

Having driven to Cincinnati to connect with my sister Sheila, we headed south into Kentucky, destined for the Blue Plum Music and Arts Festival in Johnson City, Tennessee, June 1-3.

The sun rose to greet us, as did the deep valleys and hills leading into the mountains of Appalachia. Cincinnati’s own verdant density had given me a sense of the region’s natural bounty. But once we reached increasingly southern expanses the raw magnificence rose in fullness. The broad-shouldered peaks, serenely exultant in lush greenery, unfolded in marvelously softened geometric variations as our car plunged into the highway depths.

As we descend a paved grade, vast looping angles and loping planes open before us on each side of the highway, revealing massive, undulating forms curving ahead at the fresh curve of each crest.

Turning to follow the blur beside me, I sense how modern pioneers forged roads through such rugged terrain.

The highway is cut into low mountainsides of red rock, which can be as treacherous as it is beautiful. Frequent signs warn of falling rock, and yet but the tremendous compression of fissures, severe angles and gravity create a muscular tapestry of slashed stone — grinding and shifting at the most glacial rates, rippling along in a craggy dance of asymmetric angles, slashed crevices and serrated ridges. Small foliage nestles into many of the cracks and, at times, when the rock angle leans high and back away from the highway, vines take root and cascade down over them.

I felt too emboldened by the speed of our car and the summery joy of our mission to fret over falling rocks, but other signs did dismay me. A motley array of billboards stand not on the highway shoulder — but out on many of the most sumptuous and beautiful vistas along the way. An almost perverse sense of consumer capitalism surely drives advertisers and marketers to climb up these precarious hills hauling equipment and billboards to ruin the most aesthetically pristine spots with loud, brash come-ons.

A more recent product of postmodernity rise more ominously, cell phone towers. Our society’s compulsive desire to electronically transmit information — while in transit far beyond the actual requirements of necessary communication — has created this aberration. The tripod towers stand with a militia-like sternness of randomly situated sentinels, their vertical receptor panels hovering in all directions, their thick, long cables running their full height and slithering off to power boxes at the side of the fenced-in base.

So there, throughout the rugged beauty of Appalachia — which has long signified a kind of untainted, pre-industrial primitiveness — stood the peculiar paradox of these ugly towers. They are seemingly hidden out in high, lonely hills and yet fully capable of transmitting potentially cancerous radiation into the bodies of wildlife nearby and people far away from them, via the cellphones we compulsively attach to our torsos and heads. 1

Finally arriving in Johnson City somewhat quelled my misgivings about billboard and cell tower blight. The 13th annual Blue Plum Festival proved a sense and sensibility filled delight. The streets of downtown Johnson City are jammed with food and craft vendors who benefited from a weekend of idyllic weather. A popular item was the electrical necklaces and wands that allow fest-goers to express their enjoyment of the experience in psychedelic fashion. My sister, stylish but hardly extravagant in her personal tastes, gave in and bought one of the brightly glimmering neck pieces, with a small electric guitar pendant.

Sheila also went back a second time and took some nice pictures of to the Urban Art Throwdown, a competition of graffiti artists, working in an outdoor gallery of freestanding panels arranged as folded triptychs.

The winning work included a fanciful highway scene dominated by a painted portrait of the legendary country bluesman Blind Lemon Jefferson, a perfectly apropos subject for a music festival comprising many veteran and young American roots-music musicians.

Prize-winning graffiti art at Blue Plum Festival, courtesy Johnson City Press

Prize-winning graffiti art at Blue Plum Festival, courtesy Johnson City Press

The festival headliners were Darrell Scott, Guy Clark & Verlon Thompson and the Goose Creek Symphony. Other notable talent included Malcolm Holcombe, Sol Driven Train, Dangermuffin and guitarist Eric Sommer. The festival included three other outdoor side stages, including a jazz stage (headlined by saxophonist Keith McKelley and pianist Lenore Raphael), and 12 local clubs offered live music. I’d wager that there are few American towns of this size (pop. 63,000 ) that currently have 12 live music venues. The fest also offered a kids-oriented extreme sports area, a roller derby championship and, most distinctive of all side attractions, an animation festival, with competition from filmmakers from all over the country.

Blue Plum may not be as big or as renowned as legendary Merlefest among Appalachian music festivals, but the featured roots music artists did Johnson City proud. The community is nestled in the foothills of Appalachian Mountains here in the far west corner of Tennessee, near the borders of Virginia and South Carolina. Nearby is Bristol, smack dab on the Tennessee-Virginia border, and “the birthplace of country music.”

In July of 1927, folklorist-promoter Ralph Peer recorded trainman-singer- songwriter-yodeler Jimmie Rodgers, The Carter Family and a group of other old-time musicians in Bristol. 3 The fact that two such great names in American music made seminal recordings at the same time in Bristol earned the city the distinction as country music’s official birthplace.

The Blue Plum main stage was situated at the far end of downtown Johnson City, with Buffalo Mountain standing as a majestic drop, emanating the hoary profile of the great creature for which it is named.

Several groups and performers greatly impressed me for a variety of stylistic and artistic reasons. Sol riven Train was perhaps the biggest surprise of performers unknown to me.

The served up a steaming gumbo of styles with a front line that includes saxophonist Russell Clarke and trombonist guitarist Ward Buckheister. The style is billed as “Southern roots music, New Orleans brass and Afro-Caribbean rhythm,” and it’s surely something I didn’t expect at a festival in Appalachia. But then, that’s a presumption of cultural stereotype because this fest proved remarkably cosmopolitan and eclectic. Sol Driven Train rides a high-spirited yet extremely skilled style, especially with its deft variations on reggae beats especially on an eloquently ardent “Toda la Gente.” Lead singer Joel Timmons has an effortlessly soulful delivery and the group’s exuberance slips into offbeat drollery with songs like “Cat in Half,” a country rock ode about breaking up and dividing up possessions, with the protagonist offering his lover: “We can cut the cat in half,” the type of contemporary song that achieves a disarmingly unsentimental poignancy. The band also had the chutzpah to close their set with five-man percussion jam, with enough rhythmic and theatrical vitality to work in a festival setting.

Goose Creek Symphony remains an excellent progressive bluegrass-country band with strong vocal harmonies. But after having broken up and reformed several times, they seemed a little dated following Sol Driven Train.

I only caught a bit of Eric Sommer’s set, on Saturday afternoon but his searing, deft and incisive guitar playing proved why he’s been such an in-demand session and touring musician for artists as gifted and diverse as Leon Redbone, Chris Smithers, John Hammond, Sarah Watkins (of Nickel Creek), Little Feat and the British new wave band Gang of Four, among others.

The South Carolina trio Dangermuffin followed with more highly accomplished yet unpretentious musicianship. Yes, they do some extended Grateful Deadly jams but rarely succumb to noodling. Not unlike Sol Driven Train, they have a near-perfect feel for the reggae groove, but with more of the Afro-pop guitar flow.

I have coincidentally written recently on my blog about the next artist, another South Carolina talent named Malcolm Holcombe, so I’ll refer you to that: https://kevernacular.com/?p=159

But at this festival, Holcombe made sure that we realized he’s one of the funnier singer-songwriters on tour today with his blend of down-home wise-cracks and eccentric passion, which includes an unnerving head shake that makes you think maybe he didn’t beat the devil, like some of the famous blues musicians his style resembles. One his hellhound-on-my-trail raps is about having “the creeps,” one of the keys to which “is not lettin’ anyone else know you have ‘em.”

“But then, you’re paranoid,” he added, with a slightly fiendish grin.

1 “The original establishment of a cell tower grid was convenient for military purposes, and (now due to the undemocratic federal Telecommunications Act of 1996). Both state and local government are prohibited from adopting emission standards that would be safer for the public than the very inadequate and dangerous levels set by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

http://www.berkeleydailyplanet.com/issue/2010-04-20/article/35079?headline=Cell-Phone-Towers-Should-We-Fear-Them—By-Raymond-Barglow-a-href-mailto-www.berkeleytutors.net-www.berkeleytutors.net-a-

So “telecom companies have carte blanche to do whatever they want without opposition. Although large groups of people are now fighting proposed cell towers all over America, they are not allowed to mention potential health effects to the city planning commissions who must approve these towers, or else the telecom companies threaten to sue the cities. And so all over America large groups of people are opposing cell towers based on any other reason they can find. The scientific evidence from all corners of the world is mounting geometrically regarding the harmful effects of towers.”

http://www.celltowerdangers.org/my-story.html

Despite German and Israeli studies that showed rates of cancer increasing for long time nearby residents, 2 American Cancer Association website currently minimizes concerns about the health risks of cell phone towers themselves. Nevertheless, the towers signify the risk of cancer that still has researchers hard at work regarding cell phones themselves — which are typically used and transported in the closest proximity to human bodies.

3 Bill Malone, Country Music U.S.A. Second Revised Edition, University of Texas Press,

2003, p.65.

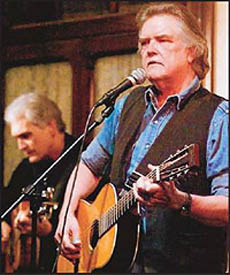

Guy Clark and Darrell Scott: Country Troubadours for the Ages

A Southerly Cultural Travel Journal Vol. 5

A prime motivation for my nearly 800-mile drive from Milwaukee to eastern Tennessee was to see the now-venerable Texas singer-songwriter Guy Clark. It was a deeply gratifying experience. Though only 70, Clark is currently walking with a cane (perhaps still suffering from effects of a broken leg in 2008) but when he settled in and warmed up with fellow guitarist and songwriter Vernon Thompson, he quickly offered several fine brand-new songs, proving his creative powers have hardly diminished. “The High Price of Inspiration” addressed how creativity is almost always inextricably entwined with life when he says he’d like “inspiration without strings I like that once.” Another new one Coyote (Spanish for trickster or, as Clark said, “coward”) pointedly conveys the wrenching story of mercenary smugglers who exploit the desperate dreams of illegal aliens along the Mexican American border: “You took all my money and left me to die in South Texas sun.”

Here you gain a sense of Clark’s distinctive artistry as his dusty, understated singing style assured that the song’s pathos would never be oversold with sentimentality. As always with Clark, the feeling are vivid in his voice but tempered by the sense one is overhearing a man singing to himself. He often sounds as if he’s just awoken from a dolorous dream. So hearing him is an utterly human experience.

Lost love, a classic theme of country music, is perfectly recast in his classic “Dublin Blues,” amid a self-assuringly jaunty beat, the protagonist rues the fading object of his love, across the Atlantic Ocean and half of America:

I wish I was in Austin/ In the Chili Parlor Bar/Drinkin’ Mad Dog Margaritas/

And not carin’ where you are.

The wishful denial expresses the emotional truth, the art of slight indirection.

Although he is also a master craftsman of guitar-making, Clark understands the proper place the material objects have in life. In “Stuff that Works,” he sings about the “kind of stuff you don’t hang on the wall/ the kind of stuff you reach for when you fall.”

His handsome face — weather-worn, craggy and now slightly collapsing – seems a prime candidate for the Great American Roots Singer-songwriter Mount Rushmore.

Just for the sake of argument, I’d also nominate Clark’s old compadre, the late Townes Van Zandt (together probably the real-life Pancho and Lefty), Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, Neil Young and maybe Lucinda Williams, as an alternate. Coincidentally the visages of all these people show the weight of their gifts and burdens, often interchangeable in nature. Calling all cultural chiselers.

Clark’s small wave to the crowd at the set’s end conveyed something, perhaps a slightly amazed humility. He has a reputation as an ornery cuss but you get the feeling that — aside from his loving competition with Van Zandt — he never wanted a whole lot more than a workbench at which he could fashion his guitars and dream up stories of desperados and desolatos to sing. Today Clark’s esteem among his contemporaries is underscored by a recent 2-CD recording of his songs by the likes of Willie Nelson, Emmylou Harris, John Prine, Roseanne Cash and others. “Guy’s songs are literature,” said Lyle Lovett, one of the artists heard on the tribute. “His ability to translate the emotional into the written word is extraordinary.”

Despite all this, I think Darrell Scott deserved the Blue Plum’s closing headliner spot, because he’s a performer in his absolute prime and a songwriter who could arguably crack into the company above. And his style connects more directly with a large crowd.

His voice can take a lyric line and hoist it from an inner feeling to an outer wail with chilling suddenness. And yet he doesn’t lose the sound of intimate probing that gives the feeling emotional honesty. His baritone-tenor range recalls Paul Simon without the tendency to preciousness.

That’s a special singing skill and his lyrics are an easy match in quality. For example, the jazzy-gospel “River Take Me” is about an out-of-work man who wants only “to live within the means of his own two hands.” When Scott sang fervently, “River take me, far from troubled times,” you sense very human desperation in the reach for a mythological metaphor: The troubled imagination must do the work that those underused hands cannot, while understanding the risk of the dream. “The river can drown you or wash you clean.”

Yet Scott looks beyond one man’s personal situation. One of his most covered songs* is “You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive,” a majestically mournful melody which commemorates the hard coal miner’s life in Harlan County, Kentucky, where “you spend your life digging coal from the bottom of your grave.” It’s the story of his own grandfather — and of many men whose lives are too proverbially close to “nasty, brutish and short.”

Scott performed with the band comprises of all his blood brothers who he said had performed together as a whole ensemble since they were teenagers. You could sense the deep history circulating among these men complex yet gone with understanding and affection.

* Kathy Mattea’s rendition of “Harlan County” is not to be missed on her album Coal.

Like this:

Like Loading...