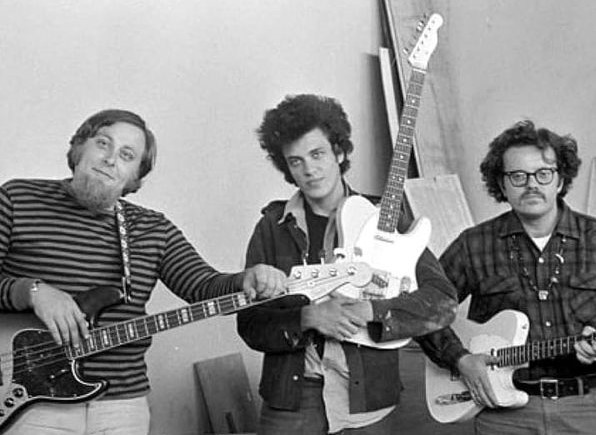

Bob Reitman and his WUWM-FM co-host, son Bob Reitman III, celebrating his 49th anniversary on radio. He retired recently after 57 years as a radio host. Courtesy Shepherd Express

Bob Reitman was always too hip to be avuncular, and yet there was always a knowing and deeply-informed manner about his music presentation over the decades. We heard and felt the easy warmth of his delivery and his concise commentary, as if you were listening to someone you could relate to even if he wasn’t related.

So what was he? it’s not too much to call him the Oracle of Alternate Milwaukee Radio, arisen in the 1960s, the man of music and poetry which shaped my generation and so music of music that ensued.

So Reitman live on the air is gone, his vibrations, sagely crafted and often transporting, now swallowed into the sounds of silence and perhaps time’s regain, imprinted on our memories.

There should be recordings of his show online. And there are intimations of more things to come on the Facebook Page of his WUWM show, titled “It’s Allright Ma (It’s Only Music)”.

I listened to him not enough in his final years co-hosting on Thursdays with his son, Bob Reitman III, on WUWM-FM, the last music program the station allowed as it moved to a talk and news radio format. He commanded that much respect. Like others, I probably assumed subconsciously he’d go on forever. At least he’s still alive, unlike too many of his important cultural contemporaries.

After all, radio was the medium in which we first experienced the explosions and sublime adventures of a generation of musicians who seemed fearless, wild and charismatic in their creative fire. And the new culture was driven by a new power of mind and spirit-expanded possibility and of protest. Through those historic decades of transformation we always had Reitman on our side. He persisted on Milwaukee radio for more than a half century.

Reitman also co-founded Milwaukee’s original alternative “underground” newspaper Kaleidoscope, as a central figure in the citiy’s alternative culture. I don’t know how much actual writing he did for the newspaper, but I do see an interview he did with rock “genius” Frank Zappa in an online PDF of an early issue.

But if there was a music journalist with the sensibility closely akin to Reitman’s it was probably Rich Mangelsdorff. So I will let him, in a Kaleidoscope essay, define a bit of the music that both he and Reitman were exploring and promoting back in the day:

“Serious rock is a constant pushing forward of the shores of awareness, expanding the frontiers of sound and, as the liner notes to Jimi Hendrix’ album state: “put(ting) the heads of . . . listeners into some novel positions,” i.e. consciousness expansion. . .

Bob Dylan’s decision to merge Woody Guthrie/Cisco Houston materials and sentiments with a rock sound (aided by blues-group musicians such as Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper) gave rise to the multi-level lyric style which is universally employed in serious rock. More tunes are direct referents to the psychedelic experience than anyone but an initiate could realize. Most can be interpreted two or three ways, easily. The best are like multi-faceted jewels allowing the mind limitless play with associations and meanings.”

— Courtesy Mike Zetteler’s blog Zonyx Report

So what Mangelsdorff dubbed “serious rock” or even “high rock” was Reitman’s bag, in spades, as much as poetic singer-songwriters. Spurred by the perhaps unprecedented spirit of cultural liberation the burgeoning Boomer generation had fed, the new rock drew on a rich array of American indigenous musics of African-Americans, as did jazz, the more self-consciously “serious” American music that I latched onto as a young aficionado and then as a music journalist.

For this reason I was personally somewhat closer to a man who paralleled Reitman’s career for a long time as a jazz disc jockey, Ron Cuzner (He later gave me a chance to succeed him when he departed from WLUM-FM). Both started at WUWM-FM and Cuzner’s late-night program followed Reitman’s nine-to-midnight slot on WZMF and several other stations they both migrated to when their fairly pure artistic standards wore out their welcome, typically with a bottom line-minded change of station management.

And yet Reitman was who I listened to probably as much as Cuzner in those early years for being on at more amenable hours and for the rich diversity of his programming. For a while he hosted at both WUWM, on “It’s All Right, Ma (It’s Only Music),” a titular takeoff of a Bob Dylan song, and at WZMF, on “The Eleventh House.” He honed his craft on the former, a public radio show, then reached a wider audience on the commercial-but-alternative ZMF and ensuing stations, with listenership following him faithfully in his migration across the dial.

A seminal event for this listener was Reitman playing “East-West,” the transporting 13-minute-plus instrumental merging Eastern classical raga, John Coltrane and blues-rock, written by guitarist Mike Bloomfield and performed by the Butterfield Blues Band. I began to understand the broader and deeper implications of the new blues-rock, and its impulse to jam, but here with a marvelous sense of form, a relationship to jazz which I was concurrently delving deeper into. This was 1966, when the Butterfield album East-West was released, a year before the music from San Francisco emerged as “the summer of love” blossomed in a psychedelic array of colors and passion.

Of course, Reitman was also Milwaukee’s first public “Dylanologist” before the term was ever coined. Who knew Bob Dylan’s music better, or presented its most politically charged music, and the inner workings of his esoterically poetical lyrics?

This combination of qualities made Reitman must-listening in an era long before the Internet and relatively easy access to recordings online. We were blessed to have the music curated by someone so gifted and insightful.

By the late 1980s, however, perhaps in the spirit of that decade, Reitman set aside his easy self-seriousness for a hidden inner performer, and did a two-man comic banter show on WKTI with Gene Mueller. The duo gained unprecedented visibility for Reitman, “pulling ridiculous stunts, hosting unhinged television specials, and even appearing on an episode of Cheers.” as Milwaukee Record recently noted.

Yet there’s another major aspect of the Godfather of Milwaukee Rock. The music experience on the radio made a quantum leap when the music became a live performance with both local groups and touring groups hitting the city.. And here again was Reitman at the fore, as the emcee for the most important and compelling of rock shows.

Fans have doubtless many memories of Reitman at the stage microphone making introductions. “My name is Reitman…” — a tall. slender figure adorned in black jeans and T-shirt, and signature black leather vest. He was really never quite a hippie “flower child” sort. He was more, a la Lou Reed, an East Coast hipster. Reed’s bracingly naked confessional song “Heroin” recorded by The Velvet Underground was also a trademark Reitman offering, helping to define and challenge the sensibilities of the time. Reitman had something of Reed’s taut poetic sensibility, without the songwriter’s irritating personal foibles. He always sounded more like an older brother, whose record collection you loved to rifle through and play.

***

Reitman also served as the figurehead host for two of the most pivotal music events in Milwaukee rock music history, which I attended. First was the three-day Midwest Rock Fest at State Fair Park in July of 1969, less than a month before Woodstock, with paper flyers promoting the forthcoming rural New York event wafting through the crowd like weed smoke.

Reitman oversaw and introduced all three days of a powerhouse lineup that may still be unequalled in the city’s history, including the freshly-minted supergroup Blind Faith, with Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker and Stevie Winwood, playing one of their first live gigs; Led Zeppelin; Joe Cocker; Jeff Beck; Johnny Winter; Jethro Tull; Bob Seeger; Kenny Rogers and the Fifth Edition; Delaney and Bonnie & Friends; Buffy Sainte-Marie; John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers; Taste, with Irish guitar virtuoso Rory Gallagher; the proto-punk band the MC5, and others, including Milwaukee’s Ox, a derivative of Clapton’s previous supergroup Cream.

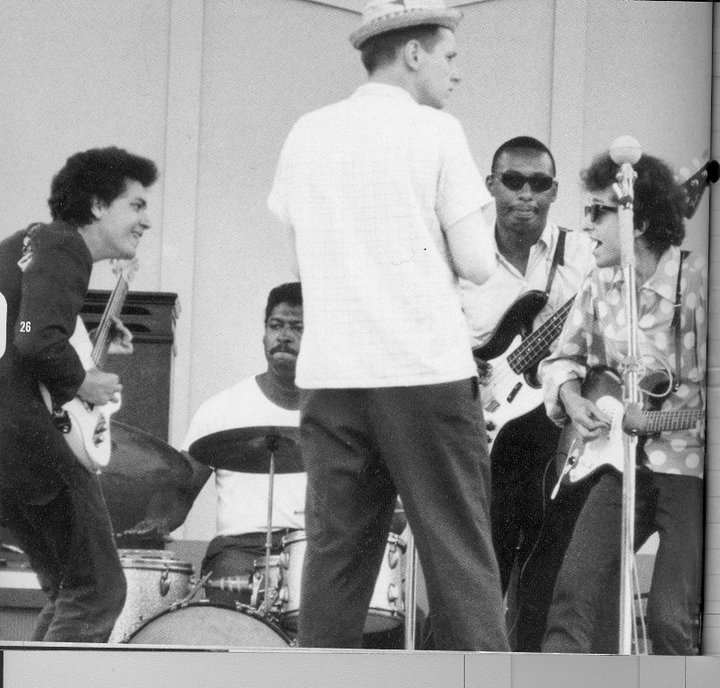

Future pop superstar Kenny Rogers, far right, leads the First Edition at Milwaukee’s Midwest Rock Fest in August 1969.

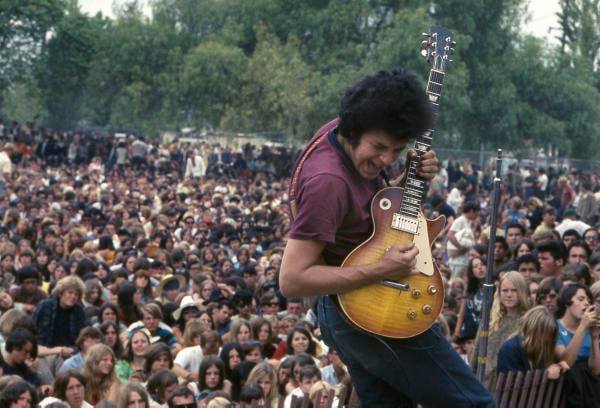

Clapton, Zepplin’s Jimmy Page, and Beck constituted the triumvirate of British blues rock guitar heroes at the time, a coup not even Woodstock could claim. Add emerging virtuoso Johnny Winter and Irish guitarist Rory Gallagher (see below) and the guitar ante is upped further. However, Blind Faith frankly seemed to be feeling their their way through their new repertoire. Still, Winwood’s effortlessly soulful singing shone. And Led Zeppelin — with Robert Plant’s overgrown trellis of blond hair and primal-scream voice rising from Hades, and Jimmy Page’s searing, ridiculously low-slug Gibson Les Paul blues guitar, sometimes played with a violin bow, amid John Bonham’s thunder ‘n’ lightning drums — made the most lasting group impression.

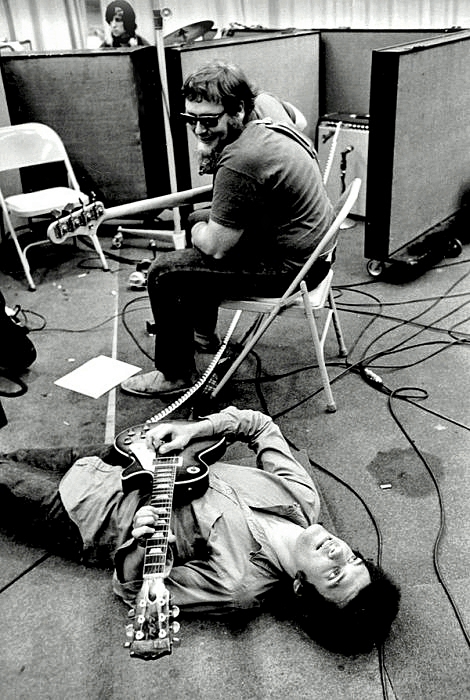

Drummer Ginger Baker of Blind Faith (left) talks with journalists at the Midwest Rock Fest at State Fair Park. Photo by Marc Dulberger

Oh yes, Ginger Baker’s exploding red hair mop and four whirling limbs delivered the most virtuosic rhythms of the fest. Yet the fest’s dark-horse winner was definitely the nearly unknown Irish power trio Taste, with Gallagher’s raucous singing and blistering guitar work. I’d rank him up with the triumvirate.

The fast-rising power trio Taste, led by Rory Gallagher (right) was the dark-horse winner among the many talented acts at Midwest Rock Fest in 1969.

This summer of ’69 was the brief, shining moment of the short-lived Golden Era of Rock Fests, with the dark clouds of Altamont in December looming on the horizon.

Reitman emceed another historic concert I saw: Bruce Springsteen, in 1975, when he was young and still relatively unknown enough to play a venue as small as Milwaukee’s Uptown, mainly a movie theater in the middle of Milwaukee. This was shortly after Springsteen’s album The Wild, The Innocent and the E-Street Shuffle and before the release of Born to Run.

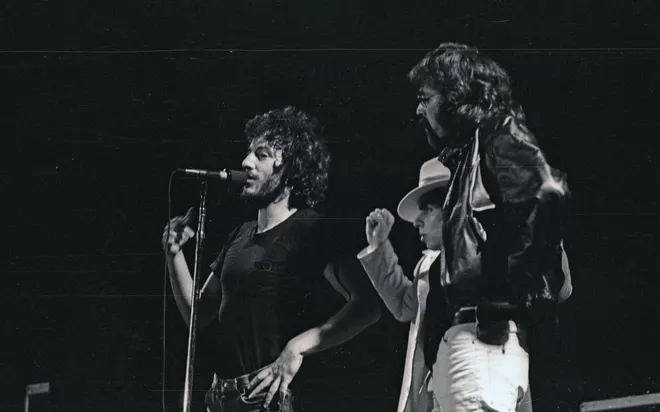

Emcee Bob Reitman, right, with Bruce Springsteen and Stevie Van Zandt (center) on Oct. 2, 1975, at Milwaukee’s Uptown Theater. Springsteen speaks to the crowd after a bomb threat was called in, forcing an evacuation and temporary suspension of the show. Photo courtesy Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

About a half hour into the show, Reitman had to come back onstage — to stop Bruce and his Street Band flying in fourth gear (how often did that ever happen?) — and announce that a bomb scare had been reported. We looked at each other, uncomprehending the impossible. We felt suspended in a heavy, humid atmosphere of collective bodily energy permeating the packed theater. But everyone had to evacuate it. Still, Reitman said, if everything proved safe and secure, the concert would continue at midnight. Springsteen promised a full show. We all dispersed to various locales and waited with a mix of horrified angst and itchy anticipation.

Who knows how the word of “all clear” got out (maybe on Reitman’s radio station) but most of us returned with, well, only blind faith.

By midnight, the place was completely packed again, and Springsteen, with a huge “where-ya-all-been” grin, and a “one-two-three-four!” relit his band’s own fiery fuse. With big saxophone honker Clarence Clemons riding shotgun, Bruce and the boys rolled down Thunder Road for at least another 190 minutes, into the wee small hours of the morning! Springsteen had hit another crest in the breaking dawn of legend. I doubt very many of his concert-goers slept much that night.

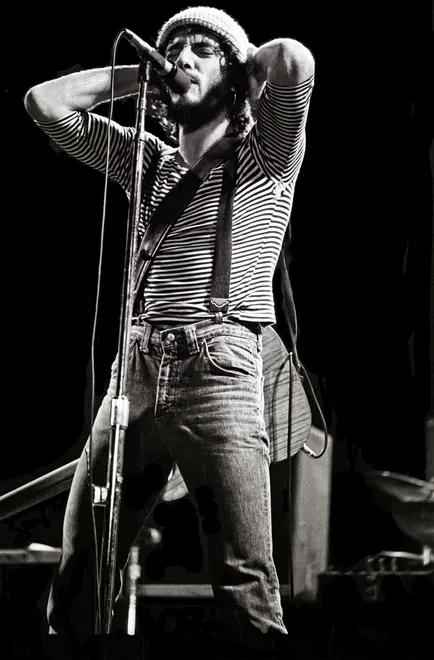

Bruce Springsteen (by then rather intoxicated according to a bandmember) performing after midnight at the Uptown when the bomb threat had been cleared. Photo by Robert Cavallo

Bruce Springsteen (by then rather intoxicated according to a bandmember) performing after midnight at the Uptown when the bomb threat had been cleared. Photo by Robert Cavallo

That seems a long time ago, but the weird and then exultant vibes of that night remain etched in my memory. And Reitman was our cultural conduit, as he has remained, though increasingly as a sort of Boomer nostalgia act, to be honest. Yet, there’s still power and value in that deep, vibrating thread of American history.

Thanks, Bob.

For a fine, concise biographic sketch of Reitman, check out Shepherd Express‘s Dave Luhrssen: https://shepherdexpress.com/news/community-news/bob-reitman-retires-from-milwaukee-radio/?utm_source=ActiveCampaign&utm_medium=email&utm_content=What+was+Bob+Reitman+s+influence+on+Milwaukee+radio%3F&utm_campaign=Daily+News+Friday+April+19%2C+2024