John Ehlers

Monthly Archives: February 2025

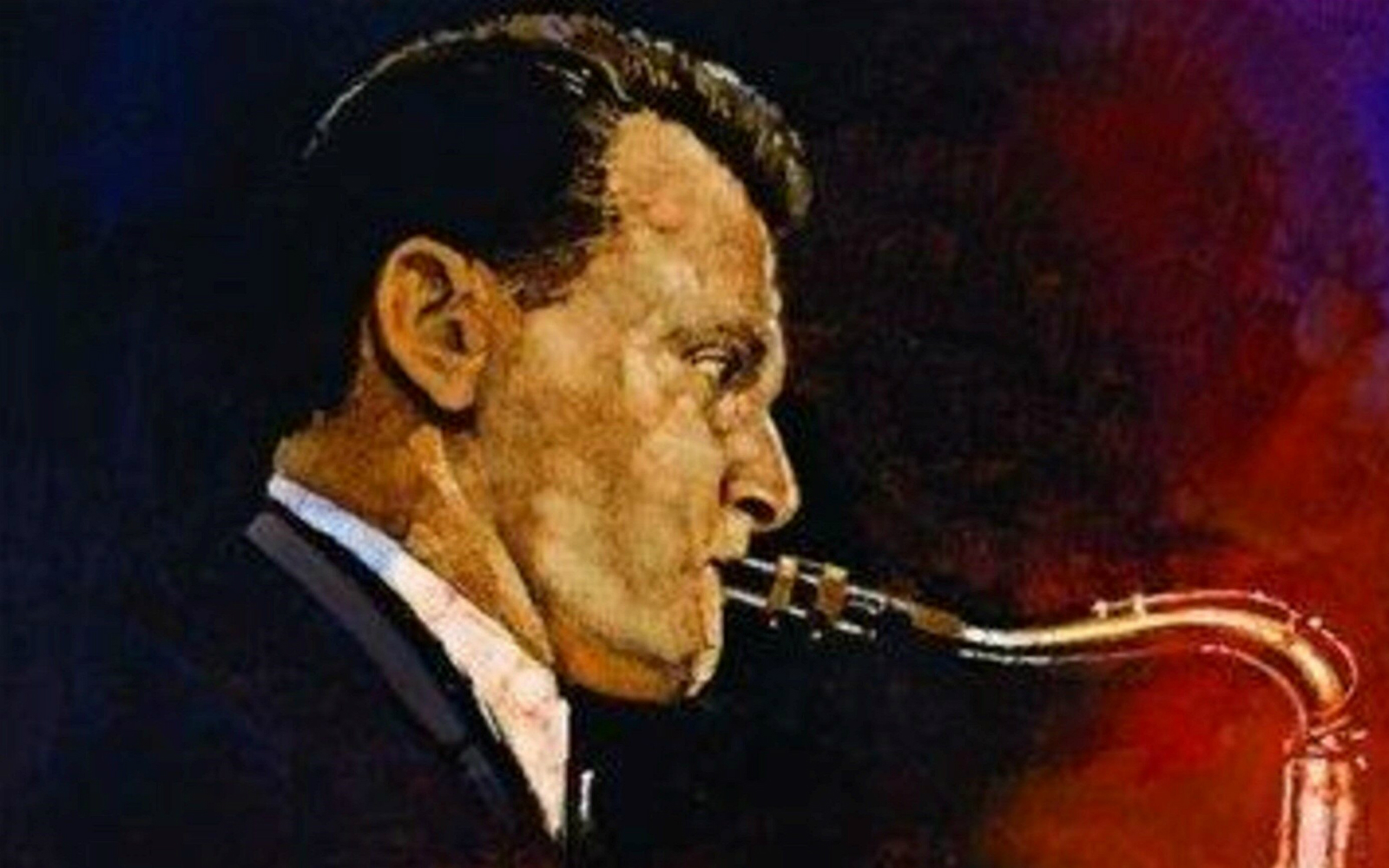

Stan Getz now? Why he still matters

Why now? Why Stan Getz now? I’d meant to post this on his birthday, February 2, but got sidetracked. Still, I post because this remains his birthday month, and because he’s a voice in time and beyond it, a voice within time and forever. Wherever I go, I’ve come to know, I yearn to hear him, and all he has to say.

I also share a warm moment with him, forever.

I understand now, as well as a non-saxophonist can, what John Coltrane meant when he said of Getz, “We’d all sound like that if we could.” Coltrane was, among other things, a supreme master of balladeering, where many saxophonists make their bid for a sound as beautiful as possible.

My own analogue to Coltrane’s indirect superlative: I would carry Getz’s sound with me further than any other instrument’s, if forced to forsake all but one. Maybe it’s a Sophie’s choice between Getz and Miles Davis.

As a relatively young music journalist, I had already reviewed a Getz performance at the Milwaukee Jazz Gallery for The Milwaukee Journal, a highlight among many superb artists I heard and reviewed there. Two years later, I interviewed him in his Chicago hotel room, then wrote a feature previewing a Getz performance at a Rainbow Summer concert in Milwaukee. There I met him again afterwards and, though brief, his thanks for the article seemed authentic. Then he surprisingly asked me to accompany him walking to his nearby hotel room, under one small condition.

Would I please carry his saxophone for him? After the performance, he was fatigued, partly the byproduct of years of abuse of his body with drugs and alcohol. He was only 57.

I accepted the task gladly, and the moment soon swelled into a thrill. I gripped and hoisted the case of one of the world’s most revered artistic instruments, beside its owner and artmaker. It inspired a short poem, “Bossa Not So Nova.”

So, I’ve written about Getz in three modes but, mea culpa, it still doesn’t seem enough.

You see, lately I’ve revisited him upon buying a used copy of the Getz musical biography Nobody Else But Me, by Dave Gelly. It discourses across the artist’s career with close readings of numerous Getz recordings, his legacy beyond memories, as he died in 1991.

This excellent book prompted me to dig out an array of Getz recordings. As I write, I’m listening to him essay “Infant Eyes,” an exquisite ballad by another giant of the tenor sax, Wayne Shorter, and each long whole note unfurls with delicious tenderness and knowing delicacy.

Here’s a link to Getz’s version of “Infant Eyes,” from the album Moments in Time: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gvr_BrW_xk0

I couldn’t have responded to this recording much earlier than a couple years ago, when I obtained a copy of this album, recorded live by Getz’s Quartet in 1976, but not released until 2016 on Resonance, a label specializing in what I’d call “jazz archeology.”

And there’s more affinity between Getz and Shorter than a few tunes in Getz’s repertoire. The sound of their voices resonates similarly, an exquisitely soft vibration, a singing like a distinctly masculine bird that — warbles and vibratos aside — can hold a note like a distant horizon of destiny. Both saxophonists have lived lives deeply shadowed by tragedy, likely informing their profound sensibilities.

Indeed now, the tune playing is “The Cry of the Wild Goose,” by trumpeter Kenny Wheeler, and it belies one misplaced reservation I held about Getz in the past.

He disabused me of it when I saw him in 1982 at the Jazz Gallery. But I’m referring to back in the mid-1960s when he broke into public awareness with his lilting bossa nova luminosities. He could hold and caress a note as if it were palpable and breathing which, with him, it truly was. Such audible tenderness enchanted me as much as any other single jazz artist did with one recording, Getz/Gilberto. Created, arranged, and recorded by virtually all Brazilian musicians, the album racked up unprecedented sales for a jazz recording (2 million copies in 1964) and became the first non-American album to win a Grammy Award for Album of the Year, in 1965.

And sure enough, right now with Horace Silver’s “Peace” (also from Moments in Time), Getz is beguiling yet again. But back during the bossa nova craze, for all my admiration, I doubted whether Getz was capable of anything approaching what I call “The Cry.”

I do hear a cry in the “wild goose cry” tune I’d just heard, but I’m referring to a sound often heard among saxophonists in the 1960s, during the same time Getz lulled and seduced with “The Girl from Ipanema.”

The notion of “The Cry” is the expressionism that numerous saxophonists especially began manifesting during that period of social upheaval and raised consciousness over racial injustice. It’s a heavily freighted topic and subtext. So perhaps its unsurprising that a naturally lyrical white saxophonist isn’t easily associated with it. Nevertheless, over the years, the true and extraordinary range of Getz’s expressive power expanded, and his version of “The Cry” arose, as such a striking contrast to his inherently singing style that it carried the weight of striking effects, like a sculptor’s chisel discharging chards and sparks, to convey how life can force us to extremes of feeling and response.

To me, Getz seemed to be universalizing the plight and poignance conveyed in “The Cry,” most often associated with African-American musicians. This is not to minimize the racial suffering those artists endured and expressed, but to find the shared humanity in it. Getz’s suffering might be arguably his own demons’ making more than of a cruel society built on systemic racism. As a Russian Jew, he may have ancestral instincts of suffering and class oppression hounding his psyche. that of the perpetul serf, in the bottom rung of an bloted monarchial system. Even today, how do those millions in the nation’s lowest caste subsist in Putin’s oligarchic, war-mongering Russia? We may hear Stan’s echo in them, too.

Accordingly, he seems a different sort of expressive animal — “Nobody Else But Me” as the biography’s title seems to borrow from his voice. The simplicity of the declaration also may reflect Getz’s uniqueness, his fingerprint identity, his sonic originality as a pied piper whom, when heard, we still feel compelled to follow, decades after bossa nova first sailed across waves and valleys. Years after his last living breath.

Gelly insightfully notes a great irony, how the drugs and liquor might’ve facilitated an “alpha state” in which, Getz explained, “the less you concentrate the better. The best way to create is to get in the alpha state…what we would call relaxed concentration.”

Such can be the price of art. Does that make it ill-begotten? Illegitimate?

Nay, I say. Thank the music gods for his voice, retrieved and captured.

Stan Getz and Astrid Gilberto in Berline 1966.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sVdaFQhS86E

Finally, here is my revised version of “Bossa Not So Nova.”

Bossa Not So Nova

Fattening and fifty-seven, Stan Getz

sweats out a melody, red-faced.

The sax sings effortlessly.

“Hey thanks for the article,

I gotta walk to the Hyatt,

can you carry my horn?” he croaks.

The sax sings light blue.

Young and tan, and tall and lovely

the girl in knee socks walks and sways.

And Stan stops his sax, and walks and goes,

“Ahhhh.”

It ain’t so much man appraising sweet youth.

Or it’s that too, with a clear trace of chagrin.

“I’m beat,” his cigarette breath bellows softly. “Just go slow.

Hey can you find a doctor?

My bass player needs one.”

His bass player?

We walk along the Milwaukee River

at 10 PM Sunday.

Is there a doctor in the river?

They’re all on-call, sleepin’ or smokin’

in a big, green, long-and-cold halllll.

Stan wonders about Mader’s, is it open do I know?

His belly rumbles southern volcanos.

The sax sings effortlessly, but just not really at me,

no, right from its case like the wind,

in her hair, in her long and lust-erous hair .

Tall and tan and young and handsome,

the boyish man from Ipanema is wheezin’

while a woman somewhere dreams…

to the old scratchy side that goes, Ahhh.

The sax singing ever so softly

as in a morning sunrise,

en la playa del aureo hombres…

(on the beach of golden men…)

(tenor sax solo to fade-out)

- Stan Getz’s saxophone case was used to store his ashes after he died of liver cancer in 1991. His ashes were then scattered into the ocean off the coast of Marina del Ray, California.

– Kevin Lynch (Kevernacular), 1988

_________

I’m hardly the only person to poeticise Getz. I imagine numerous have. One who did it as beautifully as anyone is Jim Hazard, a poet from Milwaukee who served as my primary committee-member when I did my masters in creative writing at UW-Milwaukee.

Here’s my little remembrance of Jim and his Getz poem:

Note: James Hazard was a very gifted writer and a dedicated jazz cornetist who died in 2012. (disclosure: he was a professor of mine in grad school, 22 years ago. He was a warm, funny, soulful and deeply supportive teacher, and continued to champion my career efforts over the years. He loved especially Chet Baker and Stan Getz, among many jazz musicians)

Writer and cornetist Jim Hazard with his spouse of 38 years, poet Susan Firer.

Coincidentally or not, Hazard and I both wrote Stan Getz poems. Hazard’s, “A True Biography of Stan Getz,” is great modern poetry, from this 1985 collection New Year’s Eve in Whiting Indiana, a masterful book-length ode to his hometown, shedding light on myriad shards and stories of naked, radiantly quirky humanity obscured by grimy smokestacks.

Jim’s poem suggests how Getz’s inimitable saxophone style channeled the romantic impulse in the young Hazard. My Getz poem is based on an actual encounter with Stan Getz (1927-1991), and quotes from his hit song “The Girl from Ipanema.”

Here are excerpts from:

A True Biography of Stan Getz

By James Hazard

“When you change the modes of music, the society changes.” — Confucius, via Gary Snyder

“Place yourself in the background.”, rule one , “An Approach to Style” — Strunk and White

I. 2013 Davis Ave., Whiting, Indiana

The place of his first grade appearance, 1950 or 1951. I was doing the Forbidden in the bathroom: listening to the radio while I bathed, heedless of electrocution and hoping for a jazz record , on the rhythm-and-blues Gary radio station.

Stan Getz played “Strike Up the Band” and I was heart-struck. I was already a heart-wreck, having seen Gene Tierney, her face hitting the screen as a flash flood in LAURA…

(Hearing for the first time that sound, the long and many noted phrases of it, but the sound itself carrying those long phrases out to the ends of breath as if Stan Getz’s lungs and heart would fall in on themselves, wreckage. And Gene Tierney filled one entire wall of the Hoosier Theater and like the bathroom radio – electric, fatal — could not be touched.)…

__________

Jake Heggie’s opera adaptation of “Moby-Dick” is coming to the stage, very soon.

Thar she blows!

Aye, he rises. He rises again.

Those who recently attended the visually rapturous film version of “Moby-Dick” by Wu Tsang and superbly accompanied live by Present Music in Milwaukee, take note of this:

Moby Dick does not go away. He haunts us all. The esteemed composer Jake Heggie‘s opera version of “Moby-Dick” will be staged by the Metropolitan Opera, in early March! 1.

Here’s the lowdown:

Photos from the World Premiere of Heggie’s Moby-Dick at the The Dallas Opera, 2010

_____________

- Jake Heggie is best known for his opera adaptation of the riveting and Academy Award-winning film Dead Man Walking, starring Susan Sarandon and Sean Penn.

Historian Timothy Snyder reveals the moment’s urgency pending a meeting in Munich on the Ukraine-Russian War

Ukranian soldiers disembark from a tank. Kyodo News

Timothy Snyder’s historically-informed essay is easily the most insightful writing I’ve read on the political and World War implications for appeasement of Russia, which Trump is moving heedlessly towards. Appeasement of Germany in Czechoslovakia in 1938 led to World War II. Please read this to gain understanding of where we’re now situated. Then perhaps contact one of your representatives to help send a message, at the very least.

Russia is not America’s ally. Trump and Putin in Helsinki in 2018. Brookings Institute.

Ahoy! Present Music does “Moby Dick,” as a new silent film, with live music

Moby Dick; or, The Whale

A new silent film by Wu Tsang, accompanied live by Present Music’s ensemble.

Orchestral Music composed by Caroline Shaw, Andrew Yee and Asma Maroof

***

A silent film version of Moby-Dick, accompanied by a crew of live musicians “on the deck” of the theater.

The notion intrigues and evokes…One imagines, in their questing voyage halfway around the globe, the sail-propelled whaling ship Pequod must’ve had vast stretches of yawning silence, though only from human speech.

Yet Herman Melville’s epic fictional trip, based his experience on such ships during the 19th century heyday of whaling, was surely accompanied by a layered array of sounds, musical in various ways and otherwise.

The rhythmic, surging crash and splash of the sea against the creaking wooden hull, echoing through the slats into the forecastle, the forward portion of the ship below deck where the the common crew members lived. In tight quarters with bunks against the inside hull, the rolling music of the ocean surely seeped deeply into many a seaman’s dreams. The rhythms likely reached back to Captain Ahab’s quarters.

Imagine also the ocean wind whistling and howling across the deck, and rippling and slapping powerfully against the mighty sails, causing further sequenced creaking from the wooden masts.

And, of course, sailors themelves were renowned for the sea chanteys they sang and played on fiddles and tambourines. A key character, the Black cabin boy Pip, is a tambourine player.

A silent “Moby-Dick” also recalls the first-ever film adptation of the great novel — the silent “The Sea Beast” from 1926, which starred John Barrymore as Ahab. It was remade into the first talkie version as Moby Dick in 1930, also starring Barrymore. The more definitive film version didn’t arrive until 1956 when the great director John Huston took on the project, casting Gregory Peck as Ahab, and Richard Basehart as Ishmael.

Without any modern special effects, much less digital magic, that film’s dramatic scenes of fighting the massive white sperm whale remain fairly breathtaking.

And though some questioned the casting of “good guy” Peck, he embodied the strange man’s stentorian eloquence and charisma, his stern fixation on the horizon of doomed destiny, an often-raging captain obsessed with revenge against the whale that tore off his leg and virtually demasted his manhood.

“Moby Dick; or, The Whale,’ a 2022 film by Wu Tsang, presented with a live orchestra. Photo by Diana Pfammatter, Courtesy Wu Tsang.

Silent, but not literally, is this new film by Wu Tsang (pictured at top), who is a MacArthur “genius” Fellowship winner. Along with the music, she takes the viewer by the hand in that her film does have a narrator, of sorts, though it’s not Ishmael, Melville’s narrator. Rather, in a twist, it is the book’s “sub-sub-librarian” who adapts a script from the book’s “extracts,” his eccentrically encyclopedic array of quotations about whaling that prefaces the book’s famous opening line “Call me Ishmael.”

In an interview with Flash Art, Tsang describes this “librarian”: “In our version, he lives inside the belly of the whale, and he’s a kind of a Jonah-like god figure. He can provide these different layers of research and commentary that maybe the characters in the story are not able to reflect upon themselves.” 1

Tsang explained how her interest in the subject arose only a few years ago.

“A friend of ours, a film studies scholar named Laura Harris, was giving a talk about C. L. R. James’s book Mariners, Renegades & Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In, which is a postcolonial reading of Moby-Dick.” 2

“Laura’s reading of Melville via James was an important opening that got me super excited to think about how something so old and historical can also have a very contemporary feeling to it. The book is also a prism through which to look at the present, even if it’s a very old story.”

Indeed, this writer is working on a novel about Melville, and in my extensive reading on the author and his work, James’ 1953 book remains among the most pertinent. One can argue the current crisis of leadership worldwide, where “strongman” leadership is ascendant, derives from the unregulated overabundance of capitalist economics. James, who identified as a Marxist, addressed this problem in drawing upon the clear significance of the whaling ship Pequod as a symbol for America and democracy under siege by an oppressive, self-interested leader.

Like America, Melville decribes an extremely diverse crew population, 44 men from the U.S. (including Native American), northern and southern Europe, South America, Africa, Polynesia, Iceland, the Azores, China, and India.

Monomaniacal Ahab convinces the crew to forsake its general mission of whaling, for the captain’s sole puropose — pursuing and killing Moby Dick. 3

Publicity for the new film indicates it addresses the issue of capitalism as well as colonialism.

Tsang comments in Flash Art: “Most modern forms of political leadership are not even straightforwardly about world domination or war, although we also experience that as well. It’s the drive to organize society in a capitalistic way, for an abstraction.”

In his book, James draws out the ways in which the Pequod’s crew and captain illustrate the structure of capitalism. The crew, James writes, is “living as the vast majority of human beings live . . . seeking to avoid pain and misery and struggling for happiness.”

Above them all sits Captain Ahab, the chief executive who wields centuries of accumulated knowledge and labor for his own gain, but who — not unlike Donald Trump and his circle — would blindly throw all of it into the abyss.

For James, the novel forces readers to consider whether this kind of civilization can even survive.

***

Tsang continues, “I also was looking at different research around the maritime history of that time period. There’s a book called The Many-Headed Hydra (Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, 2000) that, like C. L. R. James, focuses on the ‘motley crew’ of sailors, and how this social class of people were coming from all over the world. The book talks about how the ship was a place of mixing for cultural exchange, news and information, and even spreading revolution.”

A significant part of the cultural exchange ocurs at intimate and personal levels. Thus the new film will play up a subtext of the book, homosociality and homoeroticism.

It portrays Ishmael, the American novice sailor, and Queequeg, the Polynesian lead harpoonist, as lovers, and the ship’s crew as a community that has partly transcended gender and race. It features queer sex, costumes codesigned by Telfar Clemens and, of course, sailors grasping gelatinous whale blubber.

Melville’s book doesn’t specifically depict gay sex but it’s not difficult to imagine the goings on in a ship of men at sea for many months at a time. And in the book, Ishmael and Queequeg share a bed in a crowded New Bedford inn of necessity, yet “upon waking next daylight, I found Queequeg’s arm thrown over me in the most loving and affectionate manner,” Ishmael relates. “You had almost thought I had been his wife.” Later in the chapter “A Bosom Friend,” Ishmael continues, “how it is I know not but there is no place like a bed for confidential disclosures between friends. Man and wife, they say, there open the very bottom of their souls to each other; and some old couples often live and chat over old times till nearly morning. Thus, then, in our hearts’ honeymoon, lay I and Queequeg – a cozy, loving pair.”

And then, “and Queequeg now and then affectionately throwing his brown tattooed legs over mine, and then drawing them back; so entirely sociable and free and easy were we…”

Although long-married and the father of four children, Melville was most likely a man of strong bisexual feelings, most markedly for his fellow contemporary author Nathaniel Hawthorne, to whom he ardently dedicates “Moby-Dick.”

In her comprehensive Melville: A Biography, Laurie Robertson-Lorant insightfully writes, “His essential bisexuality, more conscious and less guilt-ridden, thanks to his sojourn in the South Seas, than that of the many repressed Victorians, would enable him to envision social organizations that would liberate human personality, not constrain it; yet he, too, was a child of his culture and his time, just as deeply wounded in his maleness as women were in their femaleness by a patriarchal culture that repressed the feminine in man and the masculine in woman…” 4

And the very end of the grand tale — with the ship sunk in a whirlpool by Moby Dick, Ishmael is the lone survivor to tell his astonishing story — carries symbolic weight regarding the profound relationship between the two shipmates, bosom frends, singers of the sea’s engulfing song.

It is a sort of call and response, Queequeg, in his final breath, in effect calls up to his friend to take his air-filled coffin, which he requested built after a near-death experience. Ishmael responds, grabbing and embracing it to his bosom and surviving afloat for several days until another passing ship finds him.

As for the film’s music score performed live, I expect Present Music to execute it with vivid aplomb and style. There are good reasons they maintain an international reputation while remaining loyally-based in the town of their birth in 1982. Their Thanksgiving concert at St. John’s Cathedral was one of the most richly diverse and moving events I’ve experienced in some time.

_____________________

- Filmmaker/installation artist Wu Tsang’s full interview with Flash Art: https://flash—art.com/article/wu-tsang/

- C.L.R. James, Mariners, Renegades and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In, c. 1953, reissued in 2001, University Press of New England, Dartmouth College (with an introduction by Donald Pease).

- In the early 1800s when “Moby-Dick” is set, whales were hunted primarily for their oil, which was used for lighting lamps, the main source of illumination before the invention of electric lights. Whale oil lamps were in use from the 1780s to around the 1860s. Over time many lamps were converted from whale oil to kerosene or camphine and eventually to electricity. Whale oil was extremely popular because it burned cleanly, brightly, and lasted longer than candles or other oil.

- Laurie Robertson-Lorant, Melville: A Biography, Clarkson Potter, 109 The “sojourn in the South Seas” the biographer references includes Melville’s time spent among the naturally unrepressed Typee people. That experience led to his first, and highly successful, semi-autobiographical book Typee, which included, for the time, quite sensual descriptions of the islanders, who often spent time in the nude.