Moby Dick; or, The Whale

A new silent film by Wu Tsang, accompanied live by Present Music’s ensemble.

Orchestral Music composed by Caroline Shaw, Andrew Yee and Asma Maroof

***

A silent film version of Moby-Dick, accompanied by a crew of live musicians “on the deck” of the theater.

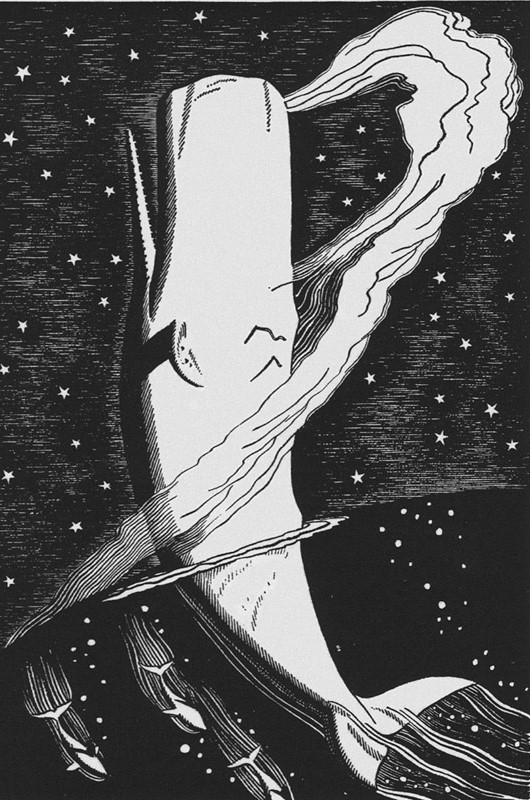

The notion intrigues and evokes…One imagines, in their questing voyage halfway around the globe, the sail-propelled whaling ship Pequod must’ve had vast stretches of yawning silence, though only from human speech.

Yet Herman Melville’s epic fictional trip, based his experience on such ships during the 19th century heyday of whaling, was surely accompanied by a layered array of sounds, musical in various ways and otherwise.

The rhythmic, surging crash and splash of the sea against the creaking wooden hull, echoing through the slats into the forecastle, the forward portion of the ship below deck where the the common crew members lived. In tight quarters with bunks against the inside hull, the rolling music of the ocean surely seeped deeply into many a seaman’s dreams. The rhythms likely reached back to Captain Ahab’s quarters.

Imagine also the ocean wind whistling and howling across the deck, and rippling and slapping powerfully against the mighty sails, causing further sequenced creaking from the wooden masts.

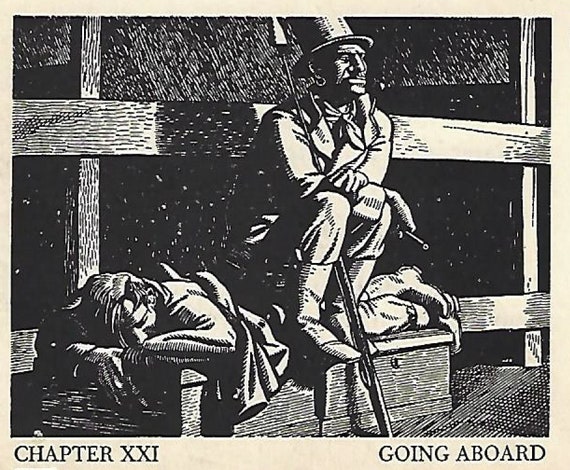

And, of course, sailors themelves were renowned for the sea chanteys they sang and played on fiddles and tambourines. A key character, the Black cabin boy Pip, is a tambourine player.

A silent “Moby-Dick” also recalls the first-ever film adptation of the great novel — the silent “The Sea Beast” from 1926, which starred John Barrymore as Ahab. It was remade into the first talkie version as Moby Dick in 1930, also starring Barrymore. The more definitive film version didn’t arrive until 1956 when the great director John Huston took on the project, casting Gregory Peck as Ahab, and Richard Basehart as Ishmael.

Without any modern special effects, much less digital magic, that film’s dramatic scenes of fighting the massive white sperm whale remain fairly breathtaking.

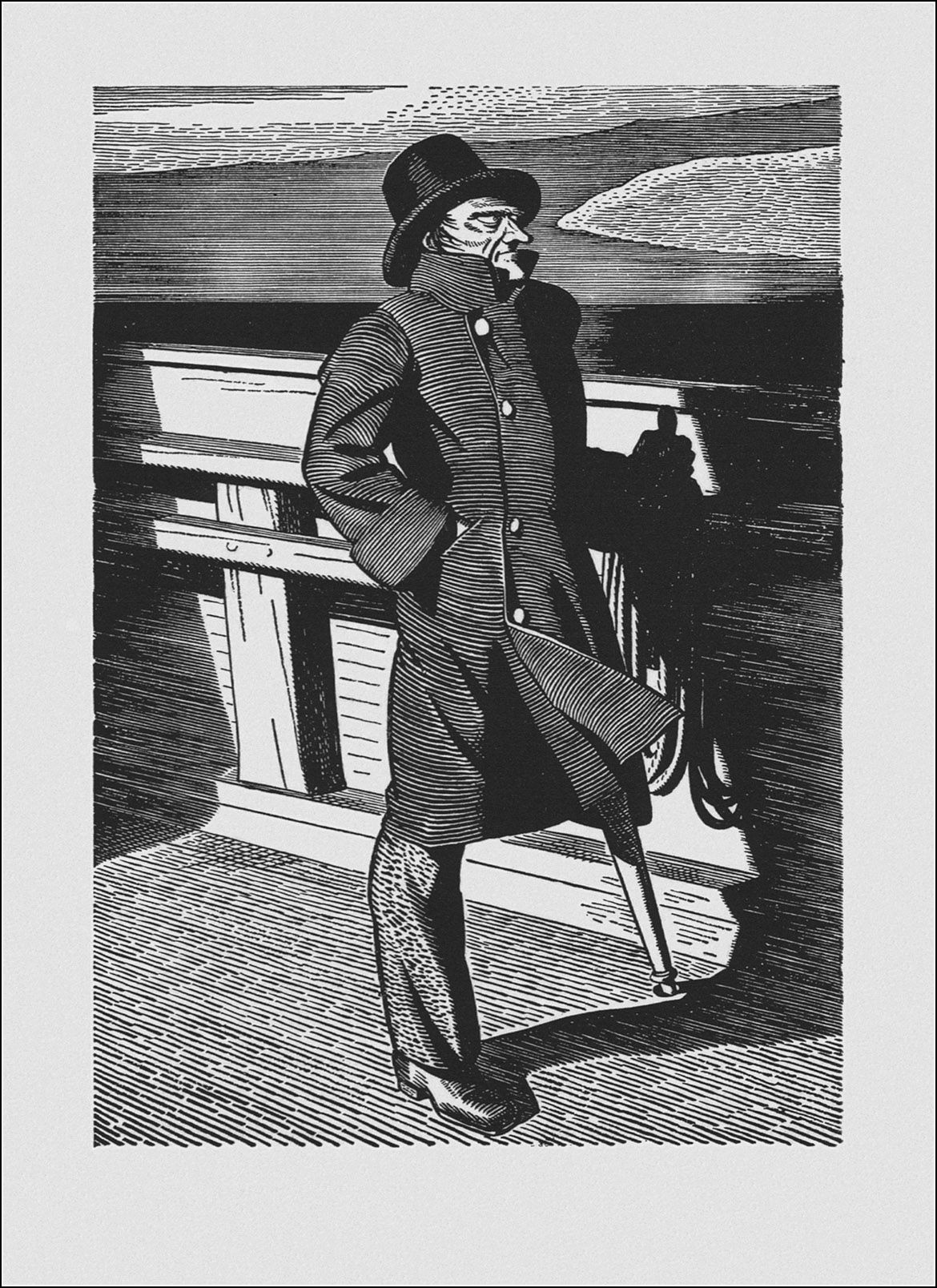

And though some questioned the casting of “good guy” Peck, he embodied the strange man’s stentorian eloquence and charisma, his stern fixation on the horizon of doomed destiny, an often-raging captain obsessed with revenge against the whale that tore off his leg and virtually demasted his manhood.

“Moby Dick; or, The Whale,’ a 2022 film by Wu Tsang, presented with a live orchestra. Photo by Diana Pfammatter, Courtesy Wu Tsang.

Silent, but not literally, is this new film by Wu Tsang (pictured at top), who is a MacArthur “genius” Fellowship winner. Along with the music, she takes the viewer by the hand in that her film does have a narrator, of sorts, though it’s not Ishmael, Melville’s narrator. Rather, in a twist, it is the book’s “sub-sub-librarian” who adapts a script from the book’s “extracts,” his eccentrically encyclopedic array of quotations about whaling that prefaces the book’s famous opening line “Call me Ishmael.”

In an interview with Flash Art, Tsang describes this “librarian”: “In our version, he lives inside the belly of the whale, and he’s a kind of a Jonah-like god figure. He can provide these different layers of research and commentary that maybe the characters in the story are not able to reflect upon themselves.” 1

Tsang explained how her interest in the subject arose only a few years ago.

“A friend of ours, a film studies scholar named Laura Harris, was giving a talk about C. L. R. James’s book Mariners, Renegades & Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In, which is a postcolonial reading of Moby-Dick.” 2

“Laura’s reading of Melville via James was an important opening that got me super excited to think about how something so old and historical can also have a very contemporary feeling to it. The book is also a prism through which to look at the present, even if it’s a very old story.”

Indeed, this writer is working on a novel about Melville, and in my extensive reading on the author and his work, James’ 1953 book remains among the most pertinent. One can argue the current crisis of leadership worldwide, where “strongman” leadership is ascendant, derives from the unregulated overabundance of capitalist economics. James, who identified as a Marxist, addressed this problem in drawing upon the clear significance of the whaling ship Pequod as a symbol for America and democracy under siege by an oppressive, self-interested leader.

Like America, Melville decribes an extremely diverse crew population, 44 men from the U.S. (including Native American), northern and southern Europe, South America, Africa, Polynesia, Iceland, the Azores, China, and India.

Monomaniacal Ahab convinces the crew to forsake its general mission of whaling, for the captain’s sole puropose — pursuing and killing Moby Dick. 3

Publicity for the new film indicates it addresses the issue of capitalism as well as colonialism.

Tsang comments in Flash Art: “Most modern forms of political leadership are not even straightforwardly about world domination or war, although we also experience that as well. It’s the drive to organize society in a capitalistic way, for an abstraction.”

In his book, James draws out the ways in which the Pequod’s crew and captain illustrate the structure of capitalism. The crew, James writes, is “living as the vast majority of human beings live . . . seeking to avoid pain and misery and struggling for happiness.”

Above them all sits Captain Ahab, the chief executive who wields centuries of accumulated knowledge and labor for his own gain, but who — not unlike Donald Trump and his circle — would blindly throw all of it into the abyss.

For James, the novel forces readers to consider whether this kind of civilization can even survive.

***

Tsang continues, “I also was looking at different research around the maritime history of that time period. There’s a book called The Many-Headed Hydra (Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, 2000) that, like C. L. R. James, focuses on the ‘motley crew’ of sailors, and how this social class of people were coming from all over the world. The book talks about how the ship was a place of mixing for cultural exchange, news and information, and even spreading revolution.”

A significant part of the cultural exchange ocurs at intimate and personal levels. Thus the new film will play up a subtext of the book, homosociality and homoeroticism.

It portrays Ishmael, the American novice sailor, and Queequeg, the Polynesian lead harpoonist, as lovers, and the ship’s crew as a community that has partly transcended gender and race. It features queer sex, costumes codesigned by Telfar Clemens and, of course, sailors grasping gelatinous whale blubber.

Melville’s book doesn’t specifically depict gay sex but it’s not difficult to imagine the goings on in a ship of men at sea for many months at a time. And in the book, Ishmael and Queequeg share a bed in a crowded New Bedford inn of necessity, yet “upon waking next daylight, I found Queequeg’s arm thrown over me in the most loving and affectionate manner,” Ishmael relates. “You had almost thought I had been his wife.” Later in the chapter “A Bosom Friend,” Ishmael continues, “how it is I know not but there is no place like a bed for confidential disclosures between friends. Man and wife, they say, there open the very bottom of their souls to each other; and some old couples often live and chat over old times till nearly morning. Thus, then, in our hearts’ honeymoon, lay I and Queequeg – a cozy, loving pair.”

And then, “and Queequeg now and then affectionately throwing his brown tattooed legs over mine, and then drawing them back; so entirely sociable and free and easy were we…”

Although long-married and the father of four children, Melville was most likely a man of strong bisexual feelings, most markedly for his fellow contemporary author Nathaniel Hawthorne, to whom he ardently dedicates “Moby-Dick.”

In her comprehensive Melville: A Biography, Laurie Robertson-Lorant insightfully writes, “His essential bisexuality, more conscious and less guilt-ridden, thanks to his sojourn in the South Seas, than that of the many repressed Victorians, would enable him to envision social organizations that would liberate human personality, not constrain it; yet he, too, was a child of his culture and his time, just as deeply wounded in his maleness as women were in their femaleness by a patriarchal culture that repressed the feminine in man and the masculine in woman…” 4

And the very end of the grand tale — with the ship sunk in a whirlpool by Moby Dick, Ishmael is the lone survivor to tell his astonishing story — carries symbolic weight regarding the profound relationship between the two shipmates, bosom frends, singers of the sea’s engulfing song.

It is a sort of call and response, Queequeg, in his final breath, in effect calls up to his friend to take his air-filled coffin, which he requested built after a near-death experience. Ishmael responds, grabbing and embracing it to his bosom and surviving afloat for several days until another passing ship finds him.

As for the film’s music score performed live, I expect Present Music to execute it with vivid aplomb and style. There are good reasons they maintain an international reputation while remaining loyally-based in the town of their birth in 1982. Their Thanksgiving concert at St. John’s Cathedral was one of the most richly diverse and moving events I’ve experienced in some time.

_____________________

- Filmmaker/installation artist Wu Tsang’s full interview with Flash Art: https://flash—art.com/article/wu-tsang/

- C.L.R. James, Mariners, Renegades and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In, c. 1953, reissued in 2001, University Press of New England, Dartmouth College (with an introduction by Donald Pease).

- In the early 1800s when “Moby-Dick” is set, whales were hunted primarily for their oil, which was used for lighting lamps, the main source of illumination before the invention of electric lights. Whale oil lamps were in use from the 1780s to around the 1860s. Over time many lamps were converted from whale oil to kerosene or camphine and eventually to electricity. Whale oil was extremely popular because it burned cleanly, brightly, and lasted longer than candles or other oil.

- Laurie Robertson-Lorant, Melville: A Biography, Clarkson Potter, 109 The “sojourn in the South Seas” the biographer references includes Melville’s time spent among the naturally unrepressed Typee people. That experience led to his first, and highly successful, semi-autobiographical book Typee, which included, for the time, quite sensual descriptions of the islanders, who often spent time in the nude.

John Coltrane “Live at Birdland.” Courtesy deep groove mono

John Coltrane “Live at Birdland.” Courtesy deep groove mono