Composer-pianist Frank Stemper. Courtesy frankstemper.com

Pound-it-out-piano player? Erstwhile composer? Slightly obsessive golfer with a chip shot on his shoulder? Whatever he is, Frank Stemper’s done gone Euro on us, proving his composer’s erst is a while around now, or ‘Round Midnight, or whatever time it is in Austria.

Best known recently in Milwaukee as a jazz pianist, most often with the brilliant bassist Hal Miller, Frank Stemper is actually a longtime composer of “legit” music, heavy on the quotation marks. That’s not because he’s not really a legit composer, as he’s highly honored in that realm. It’s because, since returning to his hometown, Stemper reclaimed jazz as his personal “classical” music, thus we look at his history in the “modern” Euro-classical tradition a tad more from the vernacular perspective.

But no doubt about it. When Beethoven hit his muse — like a musical linebacker crashing head-on — in the 1970s, Stemper was sent reeling, but soon steadied himself with a composer’s pen in hand. 1

Here’s the Beethoven bobble head Stemper received recently from your blogger for a milestone birthday. Look at that middle linebacker’s mug. Plus, Beethoven is one “middle linebacker” who, in his later years, never would’ve been drawn offside by an Aaron Rodgers “hard count,” as he was stone deaf! How he composed his late-career masterworks remains one of the miracles of the ages. Courtesy eBay 2

A Stemper friend since grade school, I wrote the poetry libretto for his doctoral dissertation work, for soprano and chamber orchestra, Seamaster, premiered in Milwaukee by Marlee Sabo and the Milwaukee Chamber Orchestra.

But Stemper has ventured oe’r rough seas to far reaches of orchestral tidal waves and islandic chamber work, since then. He spent several decades as professor of composition at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, where he first hooked up with bassist Miller, who spent a residency there, some years ago.

Stemper’s composing style, generally speaking, is post-Schoenberg expressionistic, often with almost compulsive modulations, and extreme dynamic ambushes.

He tries to harness sound, broken free from tonality, and flying. It’s usually bracing stuff and can be stimulating fun for those in the grappling mood. Among his most impressive works was a vividly-imagined piece called Secrets of War, written in response to the Illegitimate Iraq War, which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

A cursory look at the score of Symphony Number 4 (Protest), shared by the composer, suggests, amid muscular scoring, plenty of space, or grace notes, with small chamber-like details and interplays. This may reflect Mahler’s influence, though his model (such as it may remain), The Second Viennese school, employed plenty of chamber-like moments in larger orchestral scores. Beethoven’s propulsive dynamics and tempi seem inherent to Stemper’s language. Characteristically he’s more concerned with ensemble players arriving at the end of phrases or passages in rhythmic unison, rather than on pitch, allowing for freedom and ambiguity of tonality. Swift sequences of tonally chromatic sharps and flats abound, and improvised moments are invited.

Similarly, bass clef passages seem to work more for dramatic effect, than tonal grounding. One extended passage of bass clarinet and clarinet tangling with each another amidst similar byplay from bass trombone and trombone promises quasi-comical (or dangerous?) effect. Ah, such squabbling occurs in social-movement protests, certainly on the left, and most certainly on live battle lines of opposing political camps, as I’ve personally witnessed.

(The program also included Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1 and Smetana’s woozy, stirring and nationalistic Le Moldau, two pieces which faintly befit Stemper’s influences and American-oriented programmatics.)

Stemper’s oeuvre amounts to ultimately a personal, and original style of new music. sometimes delving into wit-leavened, honest sentiment, mined from his remarkable memory for historical details and contours.

By the way, his scored piano music reveals jazz influences yet often super-charged in intensity or with harmonic density and piston-like rhythms akin to Dave Brubeck, but in concentrated samples. It’s powerfully realized in the latest recording of his music, Blue 13: The Complete Piano Music of Frank Stemper, by Junghwa Lee.

The new piece, an orchestral work titled “Protest” reviewed below, also shares some qualities with “Secrets,” i.e. extra-musical sounds, bumps-in-the-night, rattles, and vocal-isms from orchestra players.

Stemper had been coy about the programmatic aspects of “Protest,” having referred to it as simply “Symphony No. 4” to his golfing buddies, perhaps fearing it might not live up to explanations even to himself, before the piece was born in performance.

As a score, the 16-minute piece seems subversive of classical symphonic notions of sonata-allegro form, based on major-minor key interplay and traditional three-part, long form. But I’ve hardly studied it extensively. The score includes instructions for ensemble players to “whisper” even at the very end. This might conveniently obscure the possibility of distracted audience members doing same, by then. But I doubt you’ll find Stemper’s music boring, though perhaps provocative of instant comment. So it goes. 3

However, the piece hardly bombed. Stemper claims it received four or five curtain calls. Nevertheless, I was told by a semi-reliable concert witness to “pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!” (opening and closing it with convenient alacrity).

Before departing overseas, Stemper betrayed natural, if comical, anxiety about the trip, since he hadn’t had an orchestral piece premiered in quite some time. So I can’t wait to actually hear it, and/or protest it.

Stemper’s music has found happy homes (though perhaps as a “problem child”) in a number of European and other foreign orchestras, including previously with conductor Guntram Simma, who commissioned this work (with funding from the city of Dornbirn) and debuted it with the Collegium Instrumentale Dornbirn.

American composer Frank Stemper (right) confers with conductor Guntram Simma during rehearsal for Stemper’s Symphony No. 4 (Protest), in Dornbirn, Austria. Photo by Nancy Stemper.

For now, we have a substantially appreciative and not overly judgmental review, by a German critic. Stemper is pictured after the performance in the bottom photo of the review layout.

If this review page opens in a German text, a mouse right click should allow you a translation function: https://www.kulturzeitschrift.at/kritiken/musik-konzert/guntram-simma-und-das-collegium-instrumentale-verstroemten-bei-dornbirn-klassik-viel-energie-und-aussagekraft

p.s. Qualifiers aside, I really do like most Stemper music that I’ve heard over the years. I’m not sure whether it likes me as much.

_________

1 The rough-and-tumble analogy to demanding modern music holds true in that pianist Stemper — a high school footballer and amateur rugby player — once badly injured one of his hands playing the “impossible” piano part of Schoenberg’s song cycle Pierrot Lunaire. Old Schoenberg clearly won that arm-wrestling match — from his grave.

2. However, I did not purchase the Beethoven bobble head from eBay, rather it came from Art Smart’s Dart Mart and Juggling Emporium, on Brady Street. in Milwaukee.

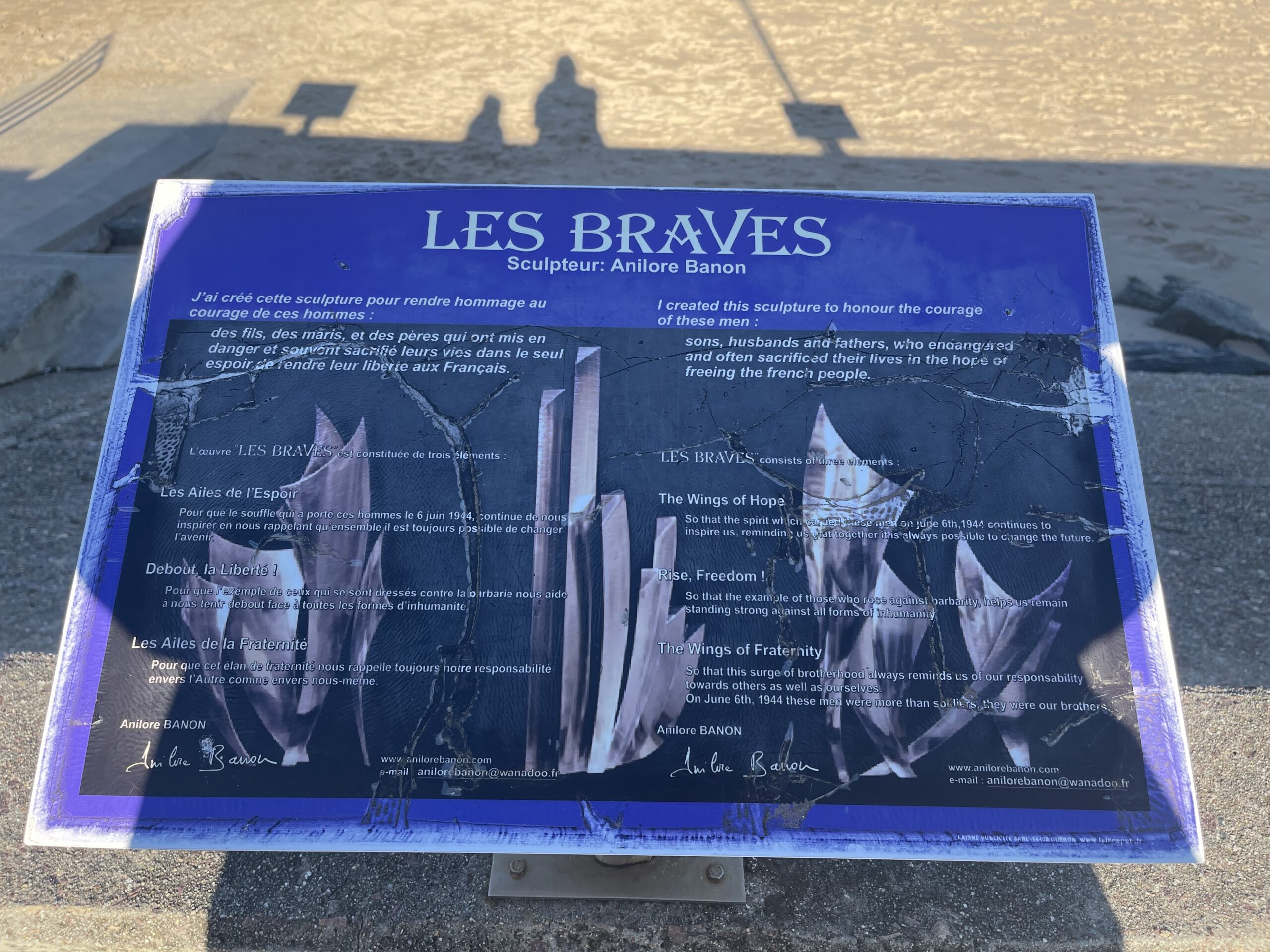

3. The Kurt Vonnegut reference above, to his famous philosophical phrase “So It goes,” from the novel Slaughterhouse Five is quoted in hopes that at least part of the implicit “protest” evoked in Stemper’s piece is anti-war, and especially meaningful for Europeans who still honor the allied D-Day invasion that turned WWII. After the performance, composer Stemper and his spouse Nancy visited Normandy Beach, France, site of D-Day in World War II. The visit to Omaha Beach prompted these reflections by composer Frank Stemper:

“I cannot imagine what it was like to be part of something so grotesque, and I am glad that I cannot imagine it. And thankful. I had to go there, I guess to thank those that had to do it. Nancy’s dad was in the Pacific building air fields on islands. The CBs. My dad was in rural Georgia taking care of German POWs – he never made it to any war zone. He was scheduled to go to serve as a shrink at the Nuremberg trials, but his points ran out and he was discharged…Gus (Valent) paid at (Guadalcanal)

The Stempers also provided these photos, including of another artist’s work, honoring that occasion (footnote photos by Nancy Stemper, unless otherwise indicated):

Omaha Beach, Normandy.

“Les Braves” Normandy beach memorial sculpture, to the fallen and the victorious, by Anilore Banon.

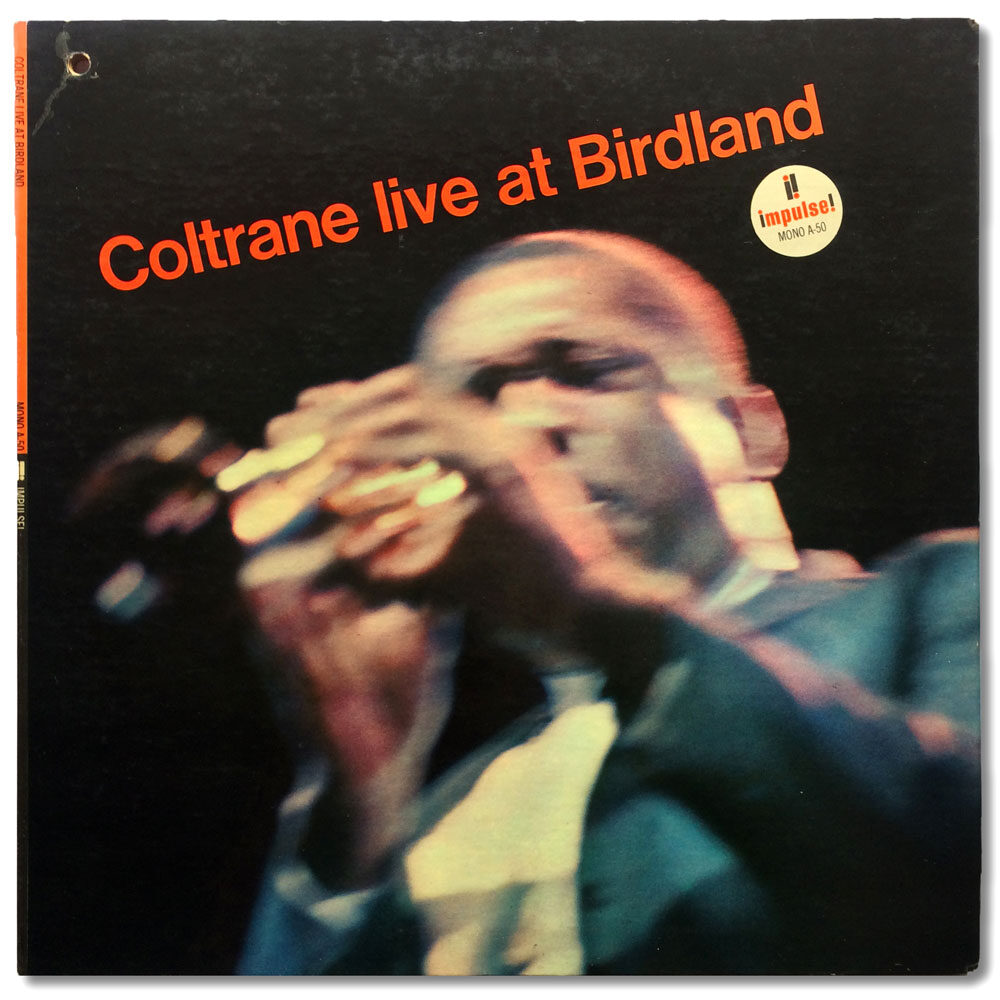

John Coltrane “Live at Birdland.” Courtesy deep groove mono

John Coltrane “Live at Birdland.” Courtesy deep groove mono