Why now? Why Stan Getz now? I’d meant to post this on his birthday, February 2, but got sidetracked. Still, I post because this remains his birthday month, and because he’s a voice in time and beyond it, a voice within time and forever. Wherever I go, I’ve come to know, I yearn to hear him, and all he has to say.

I also share a warm moment with him, forever.

I understand now, as well as a non-saxophonist can, what John Coltrane meant when he said of Getz, “We’d all sound like that if we could.” Coltrane was, among other things, a supreme master of balladeering, where many saxophonists make their bid for a sound as beautiful as possible.

My own analogue to Coltrane’s indirect superlative: I would carry Getz’s sound with me further than any other instrument’s, if forced to forsake all but one. Maybe it’s a Sophie’s choice between Getz and Miles Davis.

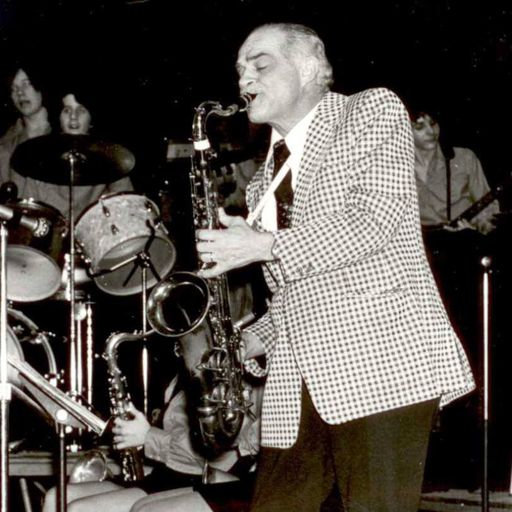

As a relatively young music journalist, I had already reviewed a Getz performance at the Milwaukee Jazz Gallery for The Milwaukee Journal, a highlight among many superb artists I heard and reviewed there. Two years later, I interviewed him in his Chicago hotel room, then wrote a feature previewing a Getz performance at a Rainbow Summer concert in Milwaukee. There I met him again afterwards and, though brief, his thanks for the article seemed authentic. Then he surprisingly asked me to accompany him walking to his nearby hotel room, under one small condition.

Would I please carry his saxophone for him? After the performance, he was fatigued, partly the byproduct of years of abuse of his body with drugs and alcohol. He was only 57.

I accepted the task gladly, and the moment soon swelled into a thrill. I gripped and hoisted the case of one of the world’s most revered artistic instruments, beside its owner and artmaker. It inspired a short poem, “Bossa Not So Nova.”

So, I’ve written about Getz in three modes but, mea culpa, it still doesn’t seem enough.

You see, lately I’ve revisited him upon buying a used copy of the Getz musical biography Nobody Else But Me, by Dave Gelly. It discourses across the artist’s career with close readings of numerous Getz recordings, his legacy beyond memories, as he died in 1991.

This excellent book prompted me to dig out an array of Getz recordings. As I write, I’m listening to him essay “Infant Eyes,” an exquisite ballad by another giant of the tenor sax, Wayne Shorter, and each long whole note unfurls with delicious tenderness and knowing delicacy.

Here’s a link to Getz’s version of “Infant Eyes,” from the album Moments in Time: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gvr_BrW_xk0

I couldn’t have responded to this recording much earlier than a couple years ago, when I obtained a copy of this album, recorded live by Getz’s Quartet in 1976, but not released until 2016 on Resonance, a label specializing in what I’d call “jazz archeology.”

And there’s more affinity between Getz and Shorter than a few tunes in Getz’s repertoire. The sound of their voices resonates similarly, an exquisitely soft vibration, a singing like a distinctly masculine bird that — warbles and vibratos aside — can hold a note like a distant horizon of destiny. Both saxophonists have lived lives deeply shadowed by tragedy, likely informing their profound sensibilities.

Indeed now, the tune playing is “The Cry of the Wild Goose,” by trumpeter Kenny Wheeler, and it belies one misplaced reservation I held about Getz in the past.

He disabused me of it when I saw him in 1982 at the Jazz Gallery. But I’m referring to back in the mid-1960s when he broke into public awareness with his lilting bossa nova luminosities. He could hold and caress a note as if it were palpable and breathing which, with him, it truly was. Such audible tenderness enchanted me as much as any other single jazz artist did with one recording, Getz/Gilberto. Created, arranged, and recorded by virtually all Brazilian musicians, the album racked up unprecedented sales for a jazz recording (2 million copies in 1964) and became the first non-American album to win a Grammy Award for Album of the Year, in 1965.

And sure enough, right now with Horace Silver’s “Peace” (also from Moments in Time), Getz is beguiling yet again. But back during the bossa nova craze, for all my admiration, I doubted whether Getz was capable of anything approaching what I call “The Cry.”

I do hear a cry in the “wild goose cry” tune I’d just heard, but I’m referring to a sound often heard among saxophonists in the 1960s, during the same time Getz lulled and seduced with “The Girl from Ipanema.”

The notion of “The Cry” is the expressionism that numerous saxophonists especially began manifesting during that period of social upheaval and raised consciousness over racial injustice. It’s a heavily freighted topic and subtext. So perhaps its unsurprising that a naturally lyrical white saxophonist isn’t easily associated with it. Nevertheless, over the years, the true and extraordinary range of Getz’s expressive power expanded, and his version of “The Cry” arose, as such a striking contrast to his inherently singing style that it carried the weight of striking effects, like a sculptor’s chisel discharging chards and sparks, to convey how life can force us to extremes of feeling and response.

To me, Getz seemed to be universalizing the plight and poignance conveyed in “The Cry,” most often associated with African-American musicians. This is not to minimize the racial suffering those artists endured and expressed, but to find the shared humanity in it. Getz’s suffering might be arguably his own demons’ making more than of a cruel society built on systemic racism. As a Russian Jew, he may have ancestral instincts of suffering and class oppression hounding his psyche. that of the perpetul serf, in the bottom rung of an bloted monarchial system. Even today, how do those millions in the nation’s lowest caste subsist in Putin’s oligarchic, war-mongering Russia? We may hear Stan’s echo in them, too.

Accordingly, he seems a different sort of expressive animal — “Nobody Else But Me” as the biography’s title seems to borrow from his voice. The simplicity of the declaration also may reflect Getz’s uniqueness, his fingerprint identity, his sonic originality as a pied piper whom, when heard, we still feel compelled to follow, decades after bossa nova first sailed across waves and valleys. Years after his last living breath.

Gelly insightfully notes a great irony, how the drugs and liquor might’ve facilitated an “alpha state” in which, Getz explained, “the less you concentrate the better. The best way to create is to get in the alpha state…what we would call relaxed concentration.”

Such can be the price of art. Does that make it ill-begotten? Illegitimate?

Nay, I say. Thank the music gods for his voice, retrieved and captured.

Stan Getz and Astrid Gilberto in Berline 1966.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sVdaFQhS86E

Finally, here is my revised version of “Bossa Not So Nova.”

Bossa Not So Nova

Fattening and fifty-seven, Stan Getz

sweats out a melody, red-faced.

The sax sings effortlessly.

“Hey thanks for the article,

I gotta walk to the Hyatt,

can you carry my horn?” he croaks.

The sax sings light blue.

Young and tan, and tall and lovely

the girl in knee socks walks and sways.

And Stan stops his sax, and walks and goes,

“Ahhhh.”

It ain’t so much man appraising sweet youth.

Or it’s that too, with a clear trace of chagrin.

“I’m beat,” his cigarette breath bellows softly. “Just go slow.

Hey can you find a doctor?

My bass player needs one.”

His bass player?

We walk along the Milwaukee River

at 10 PM Sunday.

Is there a doctor in the river?

They’re all on-call, sleepin’ or smokin’

in a big, green, long-and-cold halllll.

Stan wonders about Mader’s, is it open do I know?

His belly rumbles southern volcanos.

The sax sings effortlessly, but just not really at me,

no, right from its case like the wind,

in her hair, in her long and lust-erous hair .

Tall and tan and young and handsome,

the boyish man from Ipanema is wheezin’

while a woman somewhere dreams…

to the old scratchy side that goes, Ahhh.

The sax singing ever so softly

as in a morning sunrise,

en la playa del aureo hombres…

(on the beach of golden men…)

(tenor sax solo to fade-out)

- Stan Getz’s saxophone case was used to store his ashes after he died of liver cancer in 1991. His ashes were then scattered into the ocean off the coast of Marina del Ray, California.

– Kevin Lynch (Kevernacular), 1988

_________

I’m hardly the only person to poeticise Getz. I imagine numerous have. One who did it as beautifully as anyone is Jim Hazard, a poet from Milwaukee who served as my primary committee-member when I did my masters in creative writing at UW-Milwaukee.

Here’s my little remembrance of Jim and his Getz poem:

Note: James Hazard was a very gifted writer and a dedicated jazz cornetist who died in 2012. (disclosure: he was a professor of mine in grad school, 22 years ago. He was a warm, funny, soulful and deeply supportive teacher, and continued to champion my career efforts over the years. He loved especially Chet Baker and Stan Getz, among many jazz musicians)

Writer and cornetist Jim Hazard with his spouse of 38 years, poet Susan Firer.

Coincidentally or not, Hazard and I both wrote Stan Getz poems. Hazard’s, “A True Biography of Stan Getz,” is great modern poetry, from this 1985 collection New Year’s Eve in Whiting Indiana, a masterful book-length ode to his hometown, shedding light on myriad shards and stories of naked, radiantly quirky humanity obscured by grimy smokestacks.

Jim’s poem suggests how Getz’s inimitable saxophone style channeled the romantic impulse in the young Hazard. My Getz poem is based on an actual encounter with Stan Getz (1927-1991), and quotes from his hit song “The Girl from Ipanema.”

Here are excerpts from:

A True Biography of Stan Getz

By James Hazard

“When you change the modes of music, the society changes.” — Confucius, via Gary Snyder

“Place yourself in the background.”, rule one , “An Approach to Style” — Strunk and White

I. 2013 Davis Ave., Whiting, Indiana

The place of his first grade appearance, 1950 or 1951. I was doing the Forbidden in the bathroom: listening to the radio while I bathed, heedless of electrocution and hoping for a jazz record , on the rhythm-and-blues Gary radio station.

Stan Getz played “Strike Up the Band” and I was heart-struck. I was already a heart-wreck, having seen Gene Tierney, her face hitting the screen as a flash flood in LAURA…

(Hearing for the first time that sound, the long and many noted phrases of it, but the sound itself carrying those long phrases out to the ends of breath as if Stan Getz’s lungs and heart would fall in on themselves, wreckage. And Gene Tierney filled one entire wall of the Hoosier Theater and like the bathroom radio – electric, fatal — could not be touched.)…

__________