Zev Feldman’s reputation in the jazz world has spread to where he is a consulting producer for the legendary Blue Note label. Here he is with Blue Note president Don Was (left) in the label’s tape archives. All photos courtesy of Zev Feldman

. The name Monk for decades meant jazz giant Thelonious Monk. Then a Emmy-winning TV detective named Monk became the star of a popular series called Monk, claiming new first association for the name in popular culture.

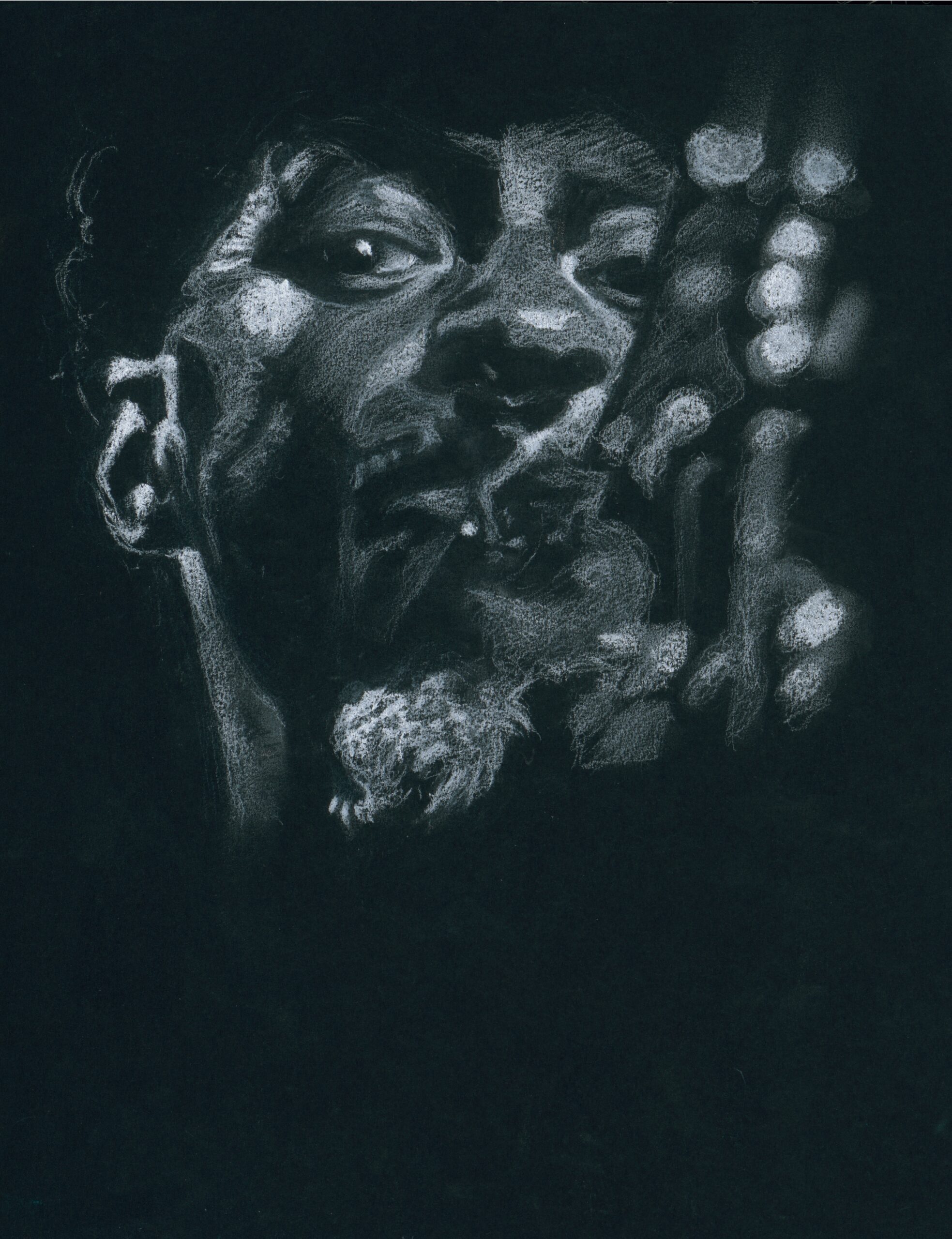

And now, along comes Zev Feldman, to take the detective role back from the TV guy, and for the sake of jazz. So now Feldman is known as “The Jazz Detective.” Detective Monk’s mystical raised hands might have a counterpart in Feldman’s internal musical dowsing rod, sensing the jazz dead, who gravely whisper, “Over here lies my best undiscovered work.”

Hearing such spectral vibes over and over, the researcher-record producer has become one of the most important non-jazz musicians in the art form, responsible for an astonishing bounty of recordings that are helping reshape the legacy of jazz history.

And his musical roots are deep, if not pure, Milwaukee.

The GRAMMY-nominated independent record producer, and the Co-President of Resonance Records, is now also a consulting producer of archival and historical recordings for Blue Note Records, the quintessential jazz label. He’s been dubbed “the Indiana Jones of Jazz” in Stereophile magazine and is widely known as the “Jazz Detective.” Over the last 25 years, he has worked for PolyGram, Universal Music Group, Rhino/Warner Music Group, and Concord Music Group, among others. In 2016, he was voted “Rising Star Producer” in Down Beat Magazine’s International Critics Poll, and he was voted “Producer of the Year” in 2022.

He’s co-produced several other labels’ important historic projects, including the acclaimed Thelonious Monk discoveries Les Liaisons Dangereuses and Palo Alto.

He also co-produced the monumental 2021 release of John Coltrane, A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle on Impulse! Records.

Amid this auspicious career in the music’s archeological byways, Feldman found his seeming destiny when he crossed paths with “my dear friend and mentor (producer) George Klabin at Resonance Records,” he says. “Since Resonance, my life was forever transformed. I was given an intriguing proposition: if I found unreleased jazz recordings, not just reissues, but newly unearthed material, George said I could produce it for release on the label. That was like putting fire on gasoline and led directly to what I’m doing now.”

Feldman with his mentor, Resonance Records president George Klabin

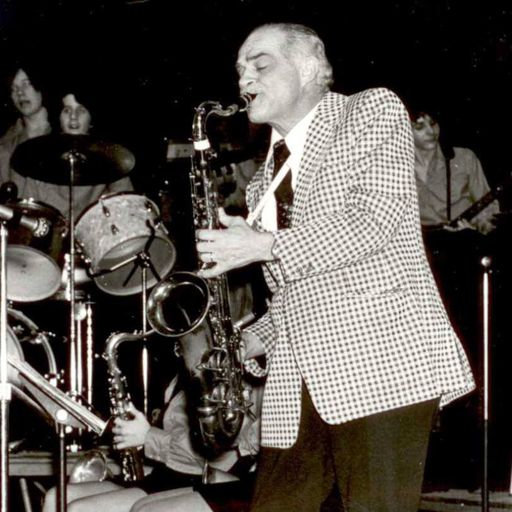

But Feldman’s back story shaped who he would become. He was born in Los Angeles, but his family moved to Madison shortly afterwards and Feldman’s passion for jazz goes to deep Milwaukee familial roots. His great uncle was the stellar Milwaukee tenor saxophonist Alvin “Abe” Aaron, who worked and toured with Les Brown (on all those famous USO tours with Bob Hope and in the studio), Dave Pell, Jack Teagarden, and others. Another uncle, Joe Aaron, also played reed instruments. Feldman’s cousin is longtime Milwaukee flutist Rick Aaron, now based in Florida. His Aunt Dora played guitar in an all-female jazz band in Milwaukee around ‘20s and ‘30s called The Bachelor’s Delight.

Feldman’s Aunt Dora (second from right) played guitar in the all-female jazz band Bachelor’s Delight in the 1920s and ’30s.

“Music, especially jazz, was always around and was passed down from the elders,” Feldman says. “It’s been part of our family’s language since I was a child.

“My mother and father (who were Milwaukee natives) had an awesome record collection in all genres of music. In high school I was all about classic rock from the Beatles, the Stones, Hendrix, the Who, but was also really digging Miles and Coltrane, and eventually the Mahavishnu Orchestra, and so much more. My most memorable live music experience in Milwaukee was seeing my great uncle Joe Aaron perform at a club when I was 18 years old and went with my great aunt, Shirley, and my grandmother. I even had a couple of Heinekens, which was very exciting.”

Feldman’s great uncle was the noted Milwaukee tenor saxophonist Joe Aaron.

Joe Aaron’s and the great tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins (left)

“Growing up, my grandparents lived right behind Peaches record store in the Silver Spring shopping center. I spent so many vacations visiting their house, and countless hours in Peaches, which eventually became a Mainstream record store. Milwaukee has always been a second home for me and I’m very lucky to be able to say so,” says Feldman, who’s formulative detecting fuel may be his passion for Kopp’s hamburgers.

Talent and Chutzpah

Since becoming a jazz music host and music director at his college radio station, Feldman’s talent and chutzpah led to progress impressively in the music business, at Polygram Records in Maryland as early as age 20 as a merchandiser and marketing specialist. He later went to Rhino Records, the reissue company, and finally national director of catalog sales for the Concord Music Group.

After a period of freelancing, he met producer George Klabin of Resonance Records in 2009. “George pulled me out of the sales and marketing realm and put me on the production highway and I’m eternally grateful.”

Since his ground-breaking success at Resonance, Feldman has co-founded a similar label, Elemental Records, and is now releasing with his own “Jazz Detective” imprint. Among the other dazzling array of historical recordings Feldman has dug up over the

The Jazz Detective label logo

years for either label are no less than eight recordings by the beloved, influential pianist Bill Evans, and five by iconic guitarist Wes Montgomery, as well as recordings by Sonny Rollins, Sarah Vaughan, Stan Getz, Charles Lloyd, Eric Dolphy, Jaco Pastorius, Grant Green, Shirley Horn, Woody Shaw, The Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchesatra, and Larry Young, among others. Most recently the acclaimed finds have included “The Lost Album from Ronnie Scott’s” by Charles Mingus for Resonance.

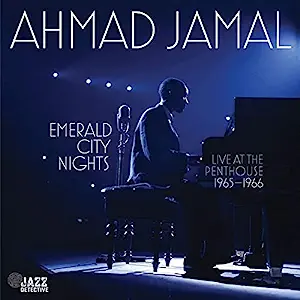

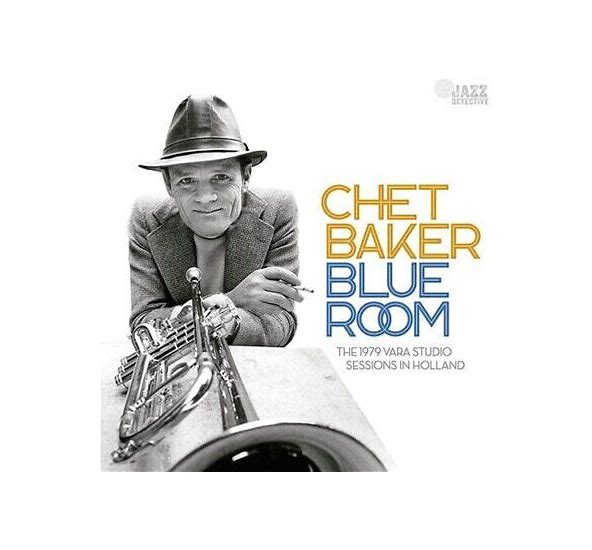

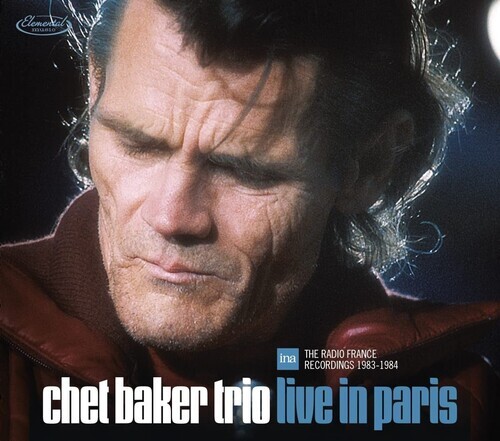

From Elemental has come the massive five-LP, three-CD set of Albert Ayler’s Revelations: The Complete ORTF 1970 Fondation Maeght Recordings. Jazz Detective has recently released two double-disc sets of Ahmad Jamal Emerald City Night: Live at the Penthouse, Sonny Stitt’s Live in Baltimore and Chet Baker’s Blue Room: The 1979 Vara Studio Sessions in Holland, which followed a superb Baker Live in Paris trio album from 1983-84. Both Baker sets give a good idea what the often-sublime trumpeter-singer sounded like when he performed between those two dates at the Milwaukee Jazz Gallery in 1981, which this writer reviewed. 1

No Bootlegs

It’s important to understand the consistent quality of Feldman’s recordings. He never settles for crudely recorded “bootlegs” no matter how great the artists. Rather, he finds tapes done on high-grade recording equipment or, as with Baker’s Live in Paris, professionally recorded for Radio France, but never released as albums. And his packaging always includes substantial critical liner notes, unpublished photos and interviews with artists, often conducted by Feldman.

“For me, it’s literally about pulling out all the stops, and bringing a story to life,” Feldman says. “I truly want to elevate the art of record making…We brought a style, sensibility and classiness to the presentation, and made it completely legal and official with all the rights holders being cleared and compensated.”

A recent Zev Feldman unearthing, a recording of trumpeter-singer Chet Baker live in Paris.

The multiple Evans and Montgomery projects have been memorable experiences for Feldman, as well as historically redefining the artists’ oeuvre.

“Getting a chance to know the families of Wes Montgomery and Bill Evans has been a blessing,” Feldman says. “We’ve done numerous projects together and have become good friends as well. It’s also been a thrill to work directly with Sonny Rollins, Charles Lloyd, and Ahmad Jamal, who just passed away recently. It’s so interesting because they have a chance to share their experiences and weigh in on all the elements that go into a project.”

Globetrotting “jazz detective” Zev Feldman relaxing in his music library.

No End in Sight

What’s on Feldman’s horizon?

“I’m working with the great Sonny Rollins on a four-LP box set, and he’s looking at everything that comes through and playing such an important role.” Upcoming there’s also unissued live recordings from Les McCann in 1966 and 1967. Feldman is especially excited to have recordings of Wes Montgomery with the Wynton Kelly Trio from the Half Note jazz club in New York City in 1965 (a collaboration which produced what Pat Metheny calls “the absolute greatest guitar album ever made,” Smokin’ at the Half-Note). 3.

Also, “George Klabin and I have been looking for a long time for unissued Art Tatum recordings, and we have a glorious three-LP and 2-CD package coming soon of three hours of unissued recordings.”

The sky is the limit? For Feldman, the deepest buried treasures are the limit. How many jazz ghosts would disagree?

_____________

This article was originally published in slightly different form in The Shepherd Express, here: https://shepherdexpress.com/music/music-feature/the-jazz-detective-searching-for-vintage-music/

1. My review of (and an interview feature with) Chet Baker (Aug. 7 and Aug. 12, 1981) are both in Milwaukee Jazz Gallery 1978-1984, an anthology of the venue’s press coverage and more:

2. The Ahmad Jamal Emerald City Lights sets and the Baker Blue Room set are reviewed in a separate Culture Currents blog, here:

Reviews of two notable “Jazz Detective” albums by Ahmad Jamal and Chet Baker

3. A previous 2005 release from 1965 called The Complete Live at the Half-Note (Wynton Kelly Trio with Wes Montgomery) appears to be an incomplete misnomer.

from NPR feature

REVIEW

MUSIC REVIEWS

Albert Ayler made sublime music. The world was not ready

The saxophonist’s last recorded concerts appear on ‘Revelations’

“Music is the Healing Force of the Universe” begins and ends Revelations: The Complete ORTF 1970 Fondation Maeght Recordings. The gorgeous box set — one of many archival jazz gems recently released under the care of producer Zev Feldman — features unseen photos, extensive liner notes and commentary from Ayler’s daughter, critics, producers and musicians. But more importantly, Revelations restores two full sets performed by the tenor saxophonist’s band, just months before Ayler was found floating in New York City’s East River. The circumstances around his death remain a mystery, but listening to these concerts — recorded July 25 and 27, 1970 — there’s a sense that Ayler was a musician in transition, the primordial yawp of his saxophone sparkling anew from the music of his youth.