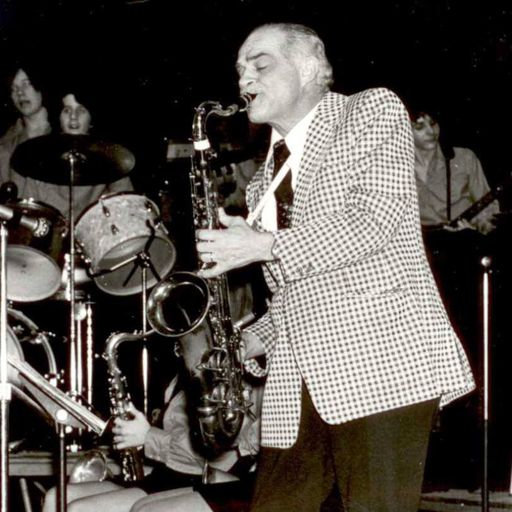

Ben Sidran. All photos via BenSidran/bensidran.com, unless otherwise credited.

Ben Sidran. All photos via BenSidran/bensidran.com, unless otherwise credited.

Ben Sidran is a hydra? After many years of observing the multitalented pianist-singer-producer-author-interviewer-broadcaster, I strive to characterize him. “Renaissance man” is a cliché nearly as old as its historical genesis. More remote yet apt, hydra, the nine-headed snake from Greek mythology, seems only a slight rhetorical exaggeration. Grappling to encompass his myriad accomplishments, I hope you get a sense of the jazz man’s vast resonance.

And yet, despite his intellectual bona fides, literary as well as musical, as a performer he’s always projected a relaxed, unassuming aura which was no less evident in a recent interview.

The occasion is Sidran’s performing with his trio in Milwaukee for the first time in many years, at Bar Centro at 8 p.m. on Thursday, September 7, even as the Madison-based Chicago native has lived virtually his whole life in the state of Wisconsin.

First, I’ll try to highlight the range of his accomplishments. He first arrived as a member of a rock band, led by Milwaukee native Steve Miller in 1968, and wrote one of Miller’s most iconic songs, “Space Cowboy.” Sidran really emerged in 1971, the year of his first album under his own name and of the important book of “jazz/sociology”: Black Talk: How the Music of Black America Created a Radical Alternative to the Values of Western Literary Tradition. That loaded subtitle says plenty about the book, which includes a forward by iconic jazz saxophonist Archie Shepp. Another scholarly Sidran work, There Was A Fire, traces the Jewish contribution to American music and The American Dream. He has also published a book of remarkably simpatico interviews with jazz musicians, and a superb autobiography, A Life in the Music.

Sidran’s album “The Concert for Garcia Lorca” was nominated for a Grammy Award. ebay.com

Among his notable recording projects over the years have included any number of albums highlighting his self-accompanied singing, an offhanded yet often pointed style. Those have ranged to a brilliantly unpredictable album recording poetry of Federico Garcia Lorca, another adapting writings of existentialist Albert Camus to song, an all-star recording adapting Hebrew wisdoms, and an album of Bob Dylan songs.

Also, he hosted a Peabody Award-winning interview program Jazz Alive on National Public Radio, and presented a Tedx Talk, “Embrace your Inner Hipster.” The hipster is a person searching for “authenticity in an age of technology,” he explained.

For all that, one thing he’d never done is record an album of piano trio music until now, with Swing State, with bassist Billy Peterson and his son Leo Sidran on drums. 1 and 2

What prompted this after all these years of jazz-related singing?

“Just what you said, never having done it, trying to keep it fresh,” Sidran replies in a phone interview. “Piano trio playing is very much part of the tradition I like, and it was a good time to make it.”

The piano trio’s seemingly stripped-down format helps prompt the question of why and how he has worked so incessantly over the years in such a vast range of expressive, conversational, and analytical modalities.

“It may sound strange but in doing all of that to me they’re not different things. Playing piano, writing, working on a book, or the radio, they were similar: they take a certain amount of focus, experience, and technique. It all basically revolves around music, it’s music-centric. So, it’s focusing on the music of people. More than the actual notes — the things that music critics get into — that means less to me than the people in the culture.”

Why did he reach so far back into the 1930s for most of the material on Swing State?

“That’s when I first started playing piano, back in the ‘50s. That’s also what I listened to. Music in the ‘30s is a lot like today playing music from the ‘90s. It seems like a long time ago now but at the time it was contemporary.”

But why play it now? “It’s just comfortable to play and I don’t have any problems playing songs that are part of the tradition. That makes sense to me, that’s what we do really.”

So, in a sense Sidran has taken a deep breath after years of artistic striving to let his fingers, instead of his voice, do the talking. He sounds both relaxed and invigorated by vintage romantic standards.

One of the most distinctive renditions is “Laura,” typically a limpid, wistful love song to a dead woman. But Sidran cuts the pathos way back, and turns it into a taut, mid-tempo exploration of almost mysterioso effect. I told him “Laura” sounded like how the late jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal might approach it. Sidran gracefully accepted the compliment, then explained that in fact Jamal had been “the guide for that arrangement.”

By contrast, the title tune is finger-popping hard bop, and that funky jazz style seems to be the dominant aspect of Sidran’s own piano style. How does hard-bop of the 1950s fit into his musical world?

“Well, it’s the style of piano playing of Bud Powell, Horace Silver, Wynton Kelly, a lot of piano players from the ‘50s and ‘60s that I grew up listening to. That’s my favorite kind of harmonic and rhythmic approach. Certainly Horace Silver categorizes as hard bop but it’s the language of the idiom of bebop.”

He’s too modest to think he’s a hydra, or plays as well as any of his favorite hard-bop pianists. But Sidran’s hydra head that actually thinks like a critic analyzed a piece by one of his favorites pianists, Sonny Clark, in these 1984 liner notes to Clark’s album My Conception. After a deft comment on the 32-bar structure of “Minor Meeting,” Sidran unfurls this lyrical description: “Sonny’s relaxed, casual attitude during his solo belies the precision of his lines and the almost literary construction of his musical ideas. It’s as if his playing is a non-verbal narrative that describes, in equal detail, both the ultimate destination of the journey and the little flowers along the way.”

But he’s a communicator in many senses so, despite Swing State, it would be a disservice to ignore his contributions as a jazz singer and producer, greatly influenced by another hipster singer-pianist, Mose Allison. He’s produced albums by Allison, Van Morrison, Rickie Lee Jones and Diana Ross. Sidran’s own most notable recent vocal recording is probably Dylan Different. How good is it? The album offers “covers that uncover a near symbiotic connection to his source’s material,” raves All-Music Guide’s knowledgeable critic Thom Jurek.

“I did the Dylan songs I grew up with in the ‘60s, the songs that I liked to listen to. I wasn’t so much making a statement about Dylan as I was reinterpreting his songs because I grew up with them and they were fun to play. Dylan has had such a long career that he’s had four or five different periods. It’s hard to summarize. So, this was a tribute to the way he approaches lyrics and putting a Ben Sidran spin on the arrangements.”

But like Dylan, Sidran can’t help making some sort of statement, and one is embedded in the title of the latest instrumental album. He’s lived most of his life in one of the most critical swing states in politics and, in that sense, beyond the uncanny rhythmic state that jazz swing evokes, political implications were intended.

“Of course, here in Wisconsin the majority of voters are Democratic but the Republicans have got the state (electoral map) so gerrymandered that they take over the (legislative) offices,” Sidran explains. “I want people to be aware that this is a swing state electorally, and it’s important to get this right, and not let one party co-opt the other.”

Sidran’s album communicates this in a subtle way, almost like subliminal messaging, as if the romance in this wordless music beckons us to not forget Martin Luther King’s dream, of human equality and opportunity for all.

This prompted me to ask him about the political implications in his first book Black Talk. He didn’t want to paraphrase a book written so long ago, which doesn’t mean it doesn’t retain relevance.

And yet he feels that something in the book’s subject, black culture, has been lost, or perhaps needs reclaiming.

“I can tell you that the music and culture that I wrote about, the black music and culture of the ‘60s has almost no references in today’s black culture. So, I can’t really speak to the music that’s current because it doesn’t reflect what was going on 50 or 60 years ago. I don’t listen, and I haven’t listened, to very much rap music, and of course that’s been the leading form of black music since the ‘90s. So, I haven’t paid attention to a lot of this stuff. I go back to rhythm and blues and bebop; it’s very hard for me to contextualize this other music which I don’t listen to.

“Maybe it needs a different labeling for me to understand discussion of what people call contemporary. I don’t recognize it in the greater subject of my book.

“The music of the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s was a great flowering, a cultural explosion of tradition. I mean there hasn’t been a greater musician than John Coltrane in 60 years. Today, there’s a lot of good young players out there. But it’s not as interesting to me as listening to Jackie McLean or, I love Eddie Harris.”

“The music I’m talking about, bebop, is still the most elegant improvisational music that has come out of America and really all around the world. It is not a particularly commercial format compared to a lot of others that have come along. It is difficult to play and difficult to listen to, in some cases.

“So, it’s not for everybody. The music that interested me made me understand American society from the inside out, to understand various aspects of what America is.”

Still swinging, Sidran stands strong by the bastions of American music history, by what we can still draw inspiration and insight, by honoring.

___________

This article was originally published in The Shepherd Express, in slightly different form, here: https://shepherdexpress.com/music/music-feature/ben-sidran-in-milwaukee-for-first-time-in-years/

- Leo Sidran also reaps a bounty of diverse musical talents: drummer-multi-instrumentalist-singer-songwriter. He also hosts an acclaimed interview podcast, The Third Story with Leo Sidran.

- A reliable source reports that Racine-based trumpeter Jamie Breiwick will be at least sitting in with Ben Sidran’s trio at Bar Centro. The following night, at 7 p.m. Friday, Sept. 8, Breiwick’s jazz-hip-hop group KASE will be recording a live album at Bar Centro with the jazz-folk group Father Sky, a.k.a. pianist-singer Anthony Deutsch.