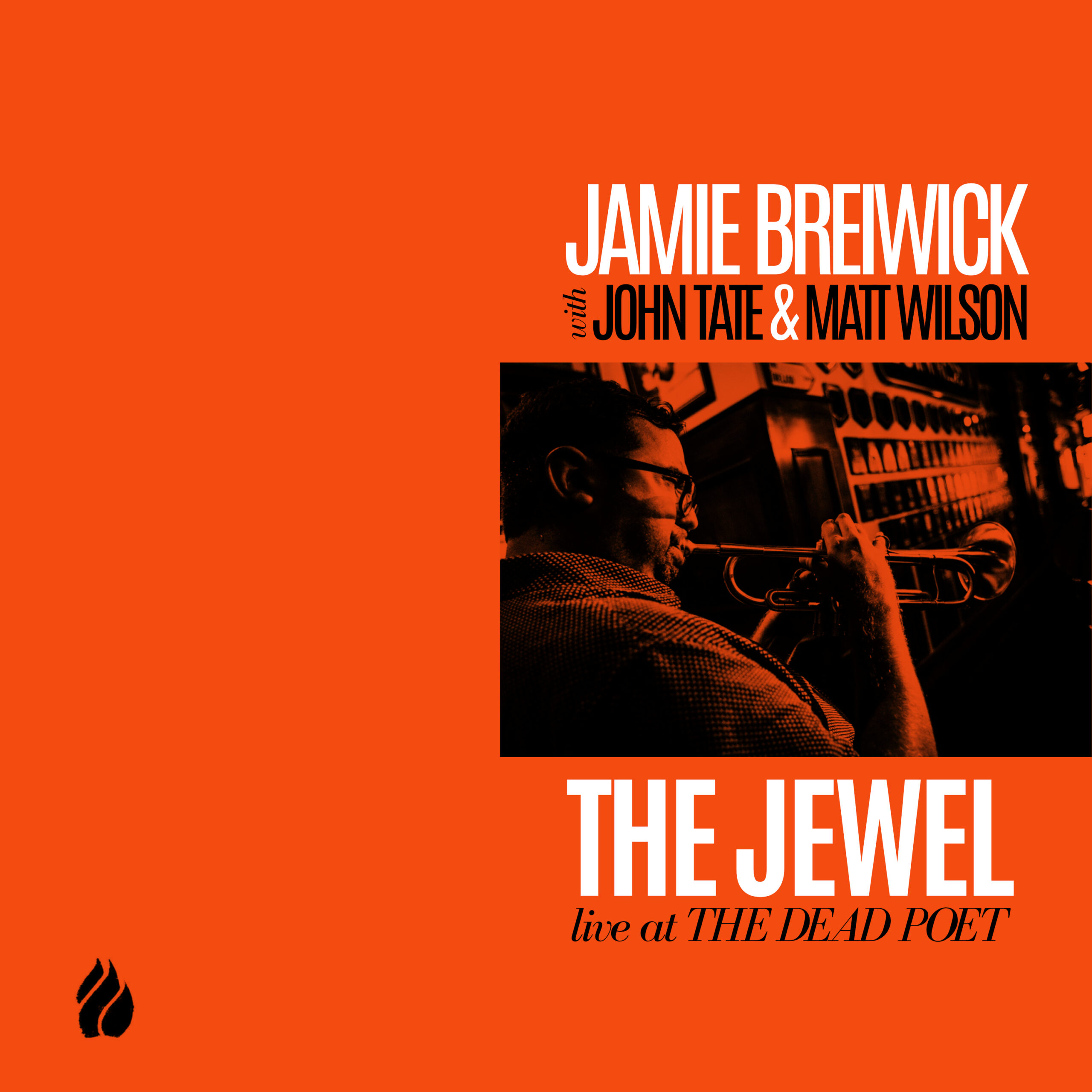

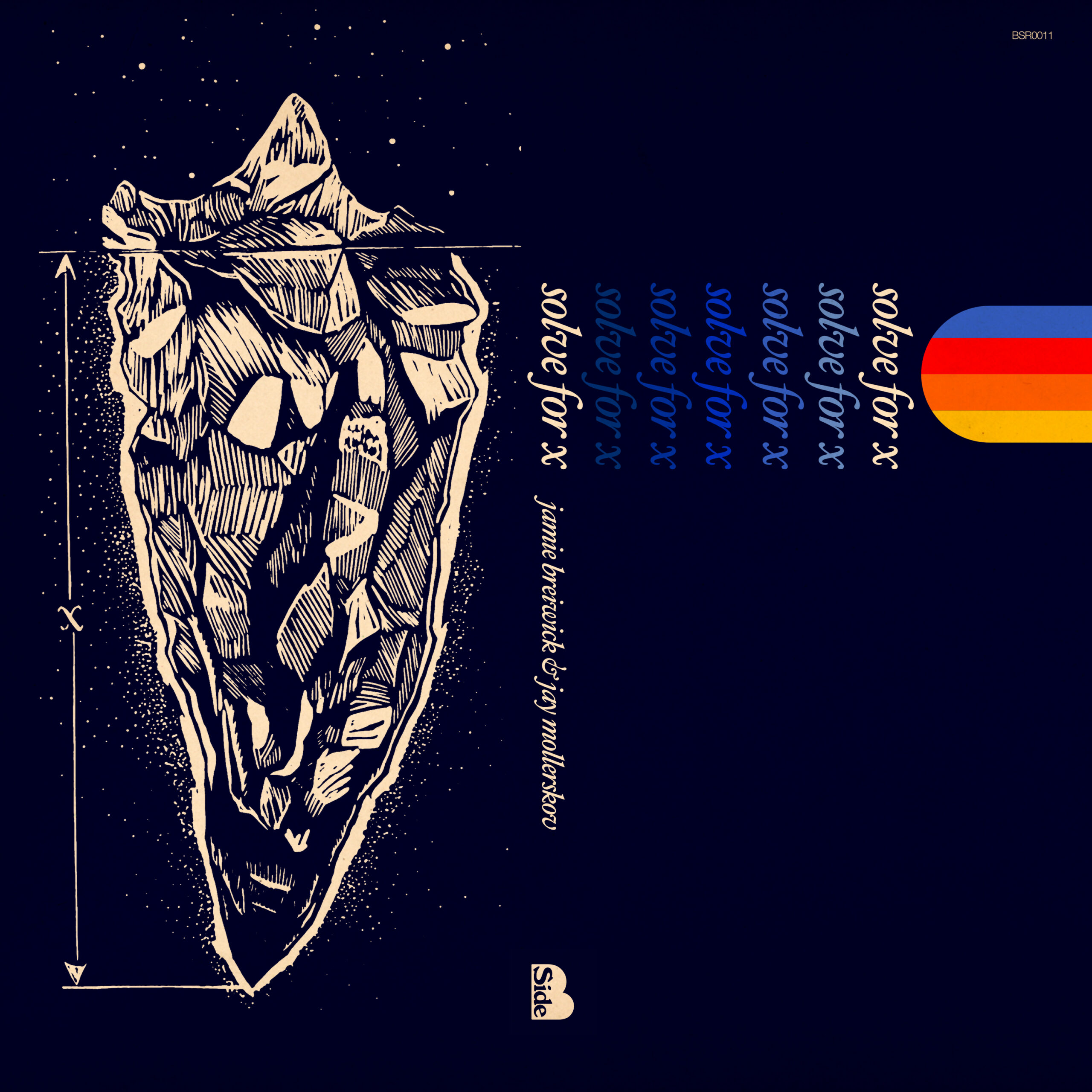

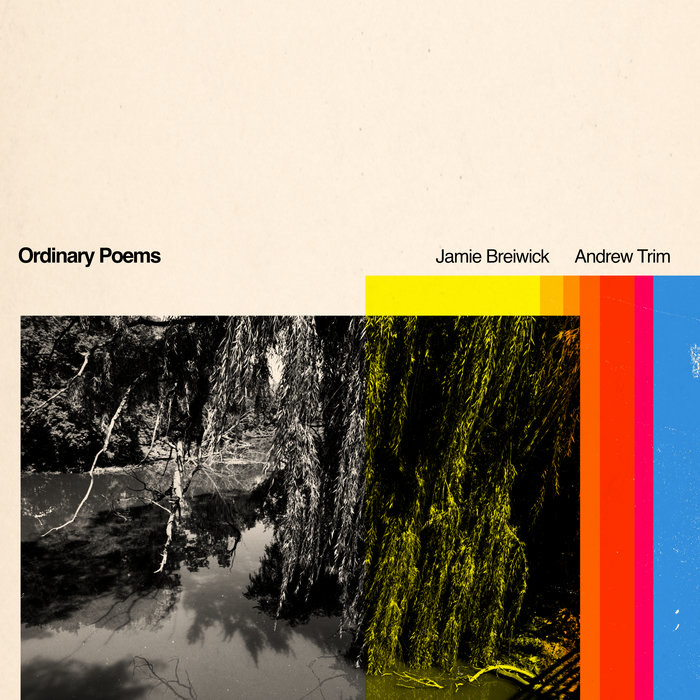

Ordinary Poems – Jamie Breiwick and Andrew Trim (B-Side and Float Free Records)

This is an enhanced version of the album liner notes I wrote for the 2024 recording “Ordinary Poems” by trumpeter Jamie Breiwick and guitarist Andrew Trim.

The noir mist clears and, amid shadows, the glint of a battered old trumpet and six steel guitar strings, maybe caught too long in the rain, perhaps the pickup bolts are beginning to rust. It’s the sound of Americana in the venerable street jazz vernacular.

In the haze one readily imagines legendary New Orleans trumpeter Buddy Bolden blowing over the rooftops and a seminal blues guitarist like Blind Lemon Jefferson. Call them “ordinary poems,” at once versified and an utterly common musical dialog between two bards of Highway 61 and The Long and Winding Road.

The actual musicians, trumpeter Jamie Breiwick and guitarist Andrew Trim, have previously worked and recorded in a myriad of contemporary contexts, from hip-hop to psychedelic, especially the voracious and prolific Breiwick.

“The conversation for the album actually started about 10 years ago when Jamie hit me up while I was still living in Chicago,” Trim recalls. “I had shared a solo guitar recording of ‘Monk’s Mood’ that laid the groundwork for getting to know each other and finding lots of musical common ground. Another big influence is a gorgeous album from 2002 called Heaven by Ron Miles and Bill Frisell. I knew Ron when I was coming up as a guitarist in Denver and studied guitar with Frisell’s old guitar teacher Dale Bruning. We wanted to make something that carried the spirit of that encounter.”

So, lean in, ordinary listener. Be entertained, enlightened, perhaps transported. And let’s toss a few dollars’ worth of affirmation into the buskers’ guitar case.

Breiwick reflects that no single word encapsulates the vast landscape of this nation’s vernacular musics — blues, folk, rock ‘n’ roll, country, gospel, bluegrass, and jazz — as well as does “Americana.”

You can’t get much more Americana than the first tune, by Trim, titled “One for Bill” – as in Bill Frisell — perhaps the paragon of a capaciously democratic genre of creativity that follows the road-weary troubadour over the rainbow and back. It’s mooning intervals whistle folkish-yet-American weird, old-timey-yet-timeless, Trim’s refrains drenched in back-alley blues.

“I wrote (it) on Frisell’s 70th birthday,” Trim says. “ ‘Ordinary Poems’ describes the beauty I found in the ordinary when deeply exploring black-and-white photography. The album cover is a collaboration between Jamie’s design and some of that photo work.”

The ensuing title tune is a thoroughly engaging melody, a contrast of tart pizzicatos and warm horn mewling, sharps and flats, hard and soft. It rides a catchy, upbeat groove recalling the Southern rock of The Allman Brothers.

” ‘Light Pollution’ is my attempt at merging the feeling of Ellington/Strayhorn with the energy of night in Chicago,” Trim explains. It may be the most eccentric piece, sounding perhaps like aural infections of sensory poisoning, the kind more starkly discernible beside the road less taken in snowy woods. Still, the wry elegance of the two simulated composers is evident.

Trim adds, “Nearly the whole record is recorded with my guitar tuned down a whole step to match the B-flat trumpet…or the lower range of a bass player. I jokingly called it ‘B-flat Guitar.’ ”

Well, no joke. Such are things that simpatico voices, like Ellington and Strayhorn, do by artistic necessity.

Trim’s “MKE Blues” tells a story all too vividly familiar to losers for a day, to urban graspers for hope.

Among Breiwick’s compositions, “Jack’s Corner” is the most daring and beautiful so far, as if interval leaps elegantly soar and twirl through wind currents, like a master carnival acrobat — in slow motion. The tune describes his son’s “creative little escape corner in our den — nod to Neil Young.”

‘Politely’ transcribes the harmonic base of early 20th-century American composer Charles Ives’ complex and dissonant The Unanswered Question with a simple, but tonal melody atop, its shapely curvature seems to suggest a question mark, or two.

“Common Origin” precisely evokes wind chimes, each sonic “cell” improvises a fragment of the chimes, like Terry Riley’s minimalist masterpiece “In C.” “Each melodic fragment is interpreted by the soloist. To perform it you move through each succession of 40 melodic fragments,” Breiwick explains.

Finally, “Dreamland” sends you off to Monkland with tenderly Thelonious turns-of-phrase evoking “Pannonica.” This is a Paul Motian-credited tune recorded by Frisell and saxophonist Joe Lovano. Monk allegedly composed it, as there’s a (never-published) bootleg recording of him playing it. Trim continues, “Somehow, I came into possession of Frisell’s hand-written chart for it which says at the top ‘Monk Played This’ (!). Dreamland is, of course, also the name of Jamie’s long-running group that plays Monk’s music.” The duo’s fine contrapuntal interplay here especially reveals guitarist Trim’s deftness at phrasing and voicings.

So, follow this wondrous road, hidden in sleepy and windswept hollows. And come back to your prosaic, ordinary life haunted in the noir of sonic wizards, drifting along the street like spirits begone.

________________

Ordinary Poems may be purchased in several forms at: https://bsiderecordings.bandcamp.com/album/ordinary-poems

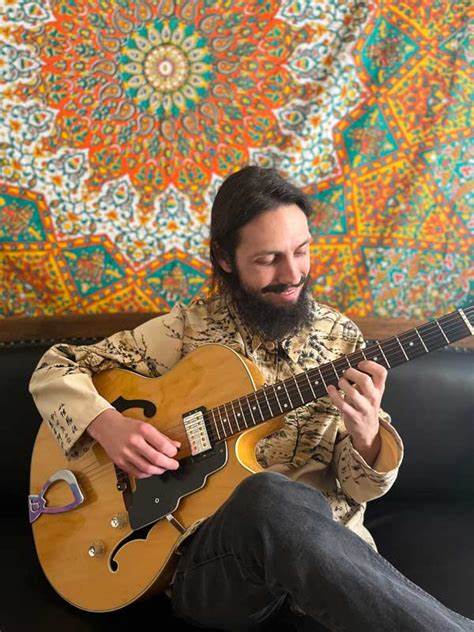

Jamie Breiwick (left), Andrew Trim, and Warhol’s Elizabeth Taylor.

Ben Sidran. All photos via BenSidran/bensidran.com, unless otherwise credited.

Ben Sidran. All photos via BenSidran/bensidran.com, unless otherwise credited.