The Waukesha nighclub Let it Be architecturally evokes the Cavern Club in Liverpool, where the Beatles first made their name. Photos courtesy GMToday.com

A Chair in the Sky: The Jazz Side of Joni Mitchell

Let it Be, 716 Clinton Street, Waukesha

Friday, October 24. Doors open 4pm; Event is from 7:00 to 9:00PM

$15 Online | $20 at the door.

Website: Chair in the Sky

********

“Oh, I wish I had a river/ I could skate away on…I made my baby cry…I’m so hard to handle/ I’m selfish and I’m sad/ Now I’ve gone and lost the best baby I ever had.”

Yes, that’s vintage Joni Mitchell, her wistfully melancholy “River” from the classic album Blue, among the songs Herbie Hancock commemorated musically on his extraordinary 2007 album River: The Joni Letters, which won both album of the year and best jazz album Grammies.

And coincidentally Hancock was the big-ticket jazz show in Milwaukee this week, and he’s earned his high prices over the decades though they’re now too steep for me, a freelance writer even with a career-long specialty in jazz. So it goes.

Still, those in my riverboat (ice-encumbered) — or on my unsteady skates – might keep pressing on to Friday night — an alternative jazz experience that’s far less expensive, being a round-the-fire gathering of gifted Milwaukee-area musicians, with an ingeniously ambitious concert concept, titled A Chair in the Sky: The Jazz Side of Joni Mitchell.

Three of the musicians are known for singing: Father Sky (a.k.a. Anthony Deutsch) and Faith Hatch, both who also play keyboards, and guitarist Garrett Waite. A fourth vocalist, drummer Hannah Johnson, will likely add more harmony for some potentially rich vocal interpretations of jazz-oriented music of the sui generis singer-songwriter Mitchell. I’d argue Mitchell’s music has had some jazzical kinship going back to that album Blue, drenched in the blues, of sorts, as only Joni could.

And the “Chair” is a song title from Mitchell’s much later self-consciously jazzy album Mingus, so it’s fair to surmise that the herculean jazz bassist-composer Charles Mingus resides in the celestial chair, though her song only references long-lost “beautiful lovers” (including musical, no doubt) and the iconic bebop-and-beyond jazz club Birdland. She had collaborated with Mingus before he died in 1979. That song’s lyrics tell a striking idiosyncratic tale, which suits the peculiarly shapely sense of harmonic charges which was fairly unique to her music and a challenge, even for many jazz musicians.

So, this event could be revelatory or memory-refreshing for many listeners, unless you’re recently immersed in the music of Mingus and comparable Mitchell work. They’ll also draw from Hancock’s River: The Joni Letters album to bring the week to an ice-sparked, pirouetting full circle, of sorts.

I haven’t yet mentioned much of the musicianship involved, or the fact this will be held in one of the Milwaukee area’s most notable new music venues, now featuring a goodly amount of jazz and related musics, Let it Be, in Waukesha, not exactly a suburb known for jazz. *

Yet the place’s name defies jazz esoterica: as Let it Be is, of course, among the most celebrated of late-era Beatles albums. At the same time, the space itself harkens to the fab four’s earliest days, with physical layout somewhat mimicking the Cavern Club in Liverpool, where the (pre-Ringo) “moptops” played a lunchtime gig in 1961 and earned five whole pounds.

Here’s some of the Beatles motif in Let It Be.

The brainchild of owner Dave Meister, Let it Be’s walls include photos documenting the Beatles’ extraordinary saga, along with a huge Union Jack flag. The club’s witty physical stylings begin with a silhouetted blackbird perched atop the outdoor overhanging sign adorned with the club’s name.

The entrance to Let It Be, at 716 Clinton Street, Wakesha.

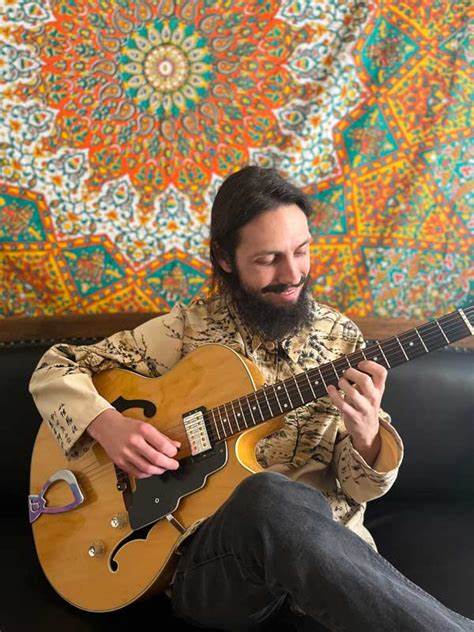

Among the vocalists of the “Chair” concept group, Father Sky sings with a depth as substantial as his epic beard’s length, having developed a broodingly echoey folk-jazz vocal style most influenced by Nina Simone. He most recerntly collaborated with the hip-hop-jazz band KASE on a live album. Further he’s one of the most ingenious pianists to emerge in the region in quite some time, with a quirky, sophisticated harmonic sense, sonic adventurousness and rhythmic attack that seem perfectly suited to do Mitchell’s work justice. (And hmm — Father Sky, did the event’s nominal concept arise from this fellow?)

Father Sky (Anthony Deutsch) will sing and play keyboards for “A Chair in the Sky: The Jazz Side of Joni Mitchell.” Courtesy bloglicense.com

In other words, he’s a soulful singer, in his way, as is Hatch in hers, so the songs’ emotional weight should carry plenty of requisite power. Guitarist-singer Waite is in the straight-ahead jazz tradition but with enough fusion overtones to capture that aspect of Mitchell’s later work.

Then there’s saxophonist Aaron van Oudenallen (a.k.a. Aaron Gardner), of the group The Erotic Adventures of the Static Chicken, who can deliver fusion jazz with a deep background in post Coltrane jazz tradition. Bassist John Christensen is among the region’s most versatile and in-demand bassists, who released a fusion album last year, Soft Rock, which received a thumbs up review from Down Beat magazine.

Hannah Johnson. Courtesy Philip Engsberg.

Finally, drummer Hannah Johnson (above, best known with the group Heirloom) plays across the area jazz scene much as any drummer these days because she’s also so versatile and drives a group with such rhythmic elan and swinging verve as to virtually “lift the bandstand” as Thelonious Monk memorably put it, a dictum that his group achieve something that “levitates” the music.

So, this adds up to a boatload of talent which prompted this preview as much as the concert concept.

So, I’d hardly presume to suggest “be there or be square,” but you could richly round out your recent musical experiences by finding a chair in this sky-seeking affair.

______________________

* Thanks to my old friend, jazz pianist-composer Frank Stemper, who played at Let It Be a while ago, and alerted me to its special qualities.

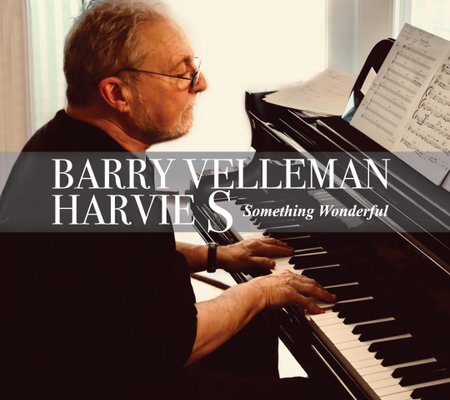

Album review: Barry Velleman/Harvie S. — Something Wonderful (RVS Records)

Album review: Barry Velleman/Harvie S. — Something Wonderful (RVS Records)