Brendan Fraser in “The Whale.” A24

After seeing the film The Whale, out newly on video (and various streaming services), it has lodged in my memory and psyche as powerfully as any recent film, including the much bigger and more commanding theater films like Oppenheimer and Killers of the Flower Moon, as excellent as those are.

This is the sort of small film that’s perfect for video viewing. It has to do with humanity on an intimate yet highly charged scale. And it deals with one of the least-acknowledged and discriminated-against minorities in our gradually and fitfully enlightened society.

That is, obese people, even morbidly obese, which is especially relevant in a state like Wisconsin, with its high percentage of overweight citizens. Beyond that, the central character is gay. I think you’ll understand, by the end, why Brendan Fraser won the best actor Oscar for 2022. Yes, he had to put on a lot of weight for the role, which can sometimes seem to beg to Academy Awards voters, and he’s courageously traveled 180 degrees from his early, ripped George of the Jungle image.

But it truly was the depths and the bubbling-right-on-the-surface humanity of his acting which made this performance special, courting greatness. He plays a huge man who never leaves his apartment and could likely never get down the flight of stairs to the parking lot. Fraser’s large blue eyes form welling pools of suffering; giving and yearning, deepened by the mass beneath them. As an obese Caucasian, he might suffer from a comparable discriminatory disdain by people who presume a person’s societal position is largely their fault, just as do so, most pointedly, many African-Americans.

So, Fraser, as Charlie, deals with his shame in various ways, including relying on a friend, Liz (Hong Chau, an Oscar nominee for the role), who is the sister of his deceased partner. She is an advisor, sounding board and enabler of his compulsive eating. You get a sense in this role of the complexity of her character, and in fact all four of the main characters in the story are richly layered.

Hong Chau as Liz in “The Whale”

Charlie teaches English online and blacks out his own video-chat window during lessons so his students can never see him. He’s significantly estranged from his teenage daughter Ellie (Sadie Sink) because he left his marriage for a lover, upon admitting his gayness, when she was eight years old. For all his fights against gravity, reaching her might be his most uphill and wrenching battle. The daughter shows up and is intensely passive-aggressive in challenging and probing her father.

Sadie Sink as Ellie in “The Whale.”

Like all-too-many-suffering minorities, Charlie struggles with low self-esteem, perhaps even strains of self-hatred. What is extraordinary about him is his capacity to see the value in others, even at the most elemental level. This makes him a wonderful teacher who is striving for the greatest possible honesty in his students, even valuing it more than conventional proprieties of English writing or exposition.

I didn’t expect Melville’s Moby-Dick to be a key motif in the story, given that I am a Melvillian of sorts. But it turns out that an essay that daughter Ellie wrote about Moby-Dick, when she was in eighth grade, is something Charlie hangs onto, for her sake as much as his own. As much as I’ve read and studied the great novel, I gained a fresh interpretive insight from Ellie’s intuition into the story, which actually befits the biography of Melville. And Charlie values the essay personally as a kind of symbolic reflection upon him, something he anguishes over and yet draws a somber sustenance from. That is partly because his daughter wrote it, and accordingly he seems to sense that each of his remote English students is a child of his. And just maybe those words will be a lifeline for Charlie from drowning in his own abyss of pathos.

A fourth key character is a quiet wildcard, Thomas (Ty Simpkins), a young man who visits Charlie and appears to be a door-to-door missionary who might (or might not) help the profoundly isolated man toward a spiritual path of redemption and self-worth. The superb Samantha Morton also plays Charlie’s ex-wife, in an intense yet briefer role.

I, for one, disagree with some critics who glibly dismiss the film as “a landmark exercise in trolling” or “misery porn” — and notice the use of the fashionable slang terms to posture the critics’ “hipness.” It now seems increasingly that every perceived experience now has a “porn” underbelly to it, often as a droll punchline. We need to accept now that film is an inherently voyeuristic art form.

Another critic “hates” the film which, she notes, received a six-minute standing ovation at the Venice Film Festival. Her big knockout zinger seems to be declaring unpersuasively that Charlie “peddles in toxic positivity,” a contrarian’s absurdly tortured phrase and notion. Rather, his “positivity” seems perhaps over the top, at times, but it is desperate, not unlike Ahab’s poor, nearly-drowned black cabin boy Pip, who at his direst moment, sees “God’s foot on the treadle of the loom.”

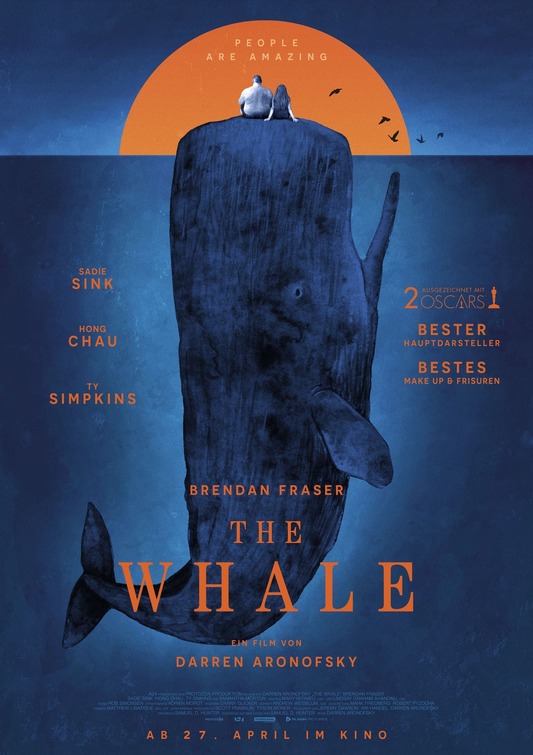

One promotional poster for “The Whale.” IMP Awards

At times, the film’s source as a play, by screenwriter Samuel D. Hunter, shows up in small, melodramatic staginess. But no, you won’t find a strong element of modernist irony in The Whale, yet I’m thankful for that. Let’s not forget Moby-Dick’s subtitle, or, The Whale. It shouldn’t be too hard to discern the elusive, great white whale as the richer signifier of this film’s title than an obvious pejorative insult. In fact, this is a courageous film in this era of both unfettered, cruel bigotry and sometimes-stifling political correctness, America’s sad polarities. Another title variation might’ve been Carson McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, but to revive that would be simply saccharine.

Brendan Fraser in a critical moment in “The Whale.”

As a title and a symbol, The Whale rides the waves of a difficult life much better, from its unfathomable depths to its improbable breach at the end, which perhaps breaches “suspension of disbelief” reality, but so be it. This is where the story was striving towards, rather than a “happy” temporal ending.

***

As a video bonus, all the lead actors, Hunter and director Darren Aronofsky, provide more-insightful-than-normal reflections, in a “making of” side feature.

______________

Kevin, this is glowing, intriguing writing.

Judy, Thank you. Your comment was succinct and well-written itself. Glad you liked the review. Kevin