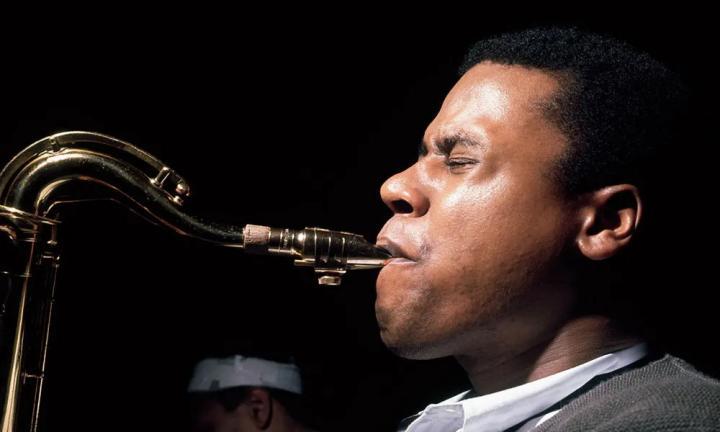

Wayne Shorter in the era of his celebrated Blue Note recordings

MADISON JAZZ FESTIVAL 2023, Review VOL. 1

This is for anyone who cares about the passing, in the eternal night, of Wayne Shorter. He was a titanic of modern jazz and jazz-fusion, and of American music in general. As with the famous Titanic, there was a certain fatefulness in him, even though he lived to 89. One of his underappreciated albums was Phantom Navigator, and his wife Ana died in 1986, at age 43, in the crash of TWA Flight 880. And his music often seemed to dwell in mystery, not unlike most of the iceberg submerged and waiting for the “unsinkable” ship liner, now once again in our consciousness, due to intrepid if fatefully foolhardy explorers.

The following video’s value is representing a live tribute by a sextet of musicians who handle an intriguing array of Wayne Shorter repertoire with aplomb and dedication as part of the recent Madison Jazz Festival.

The festival, by the way, has evolved to become, in my book, the best Midwestern jazz festival north of the inherently larger Chicago Jazz Festival. These musicians are from the Madison and Milwaukee region, but perform Shorter’s music in a representative manner, as comparable to most any region in America. The concert was at saxophonist-entrepreneur-educator Hanah Jon Taylor’s music venue Café Coda in Madison, which has been one of the Midwest’s hotbeds of such creative and improvisational music for some years now.

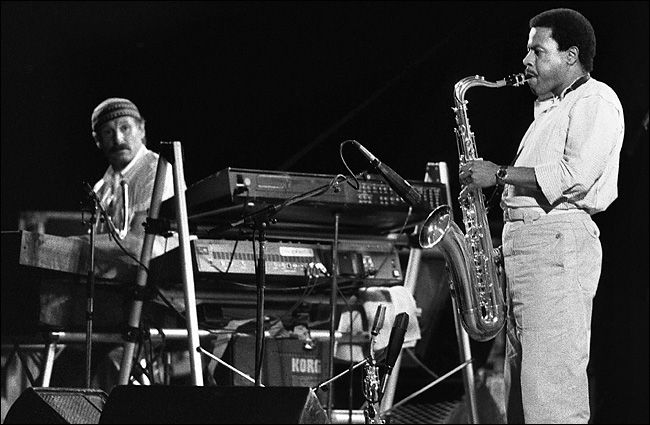

Pianist Dave Stoler (left) and bassist John Christensen from the Shorter tribute band. Tribute band photos courtesy Arts + Lit Lab

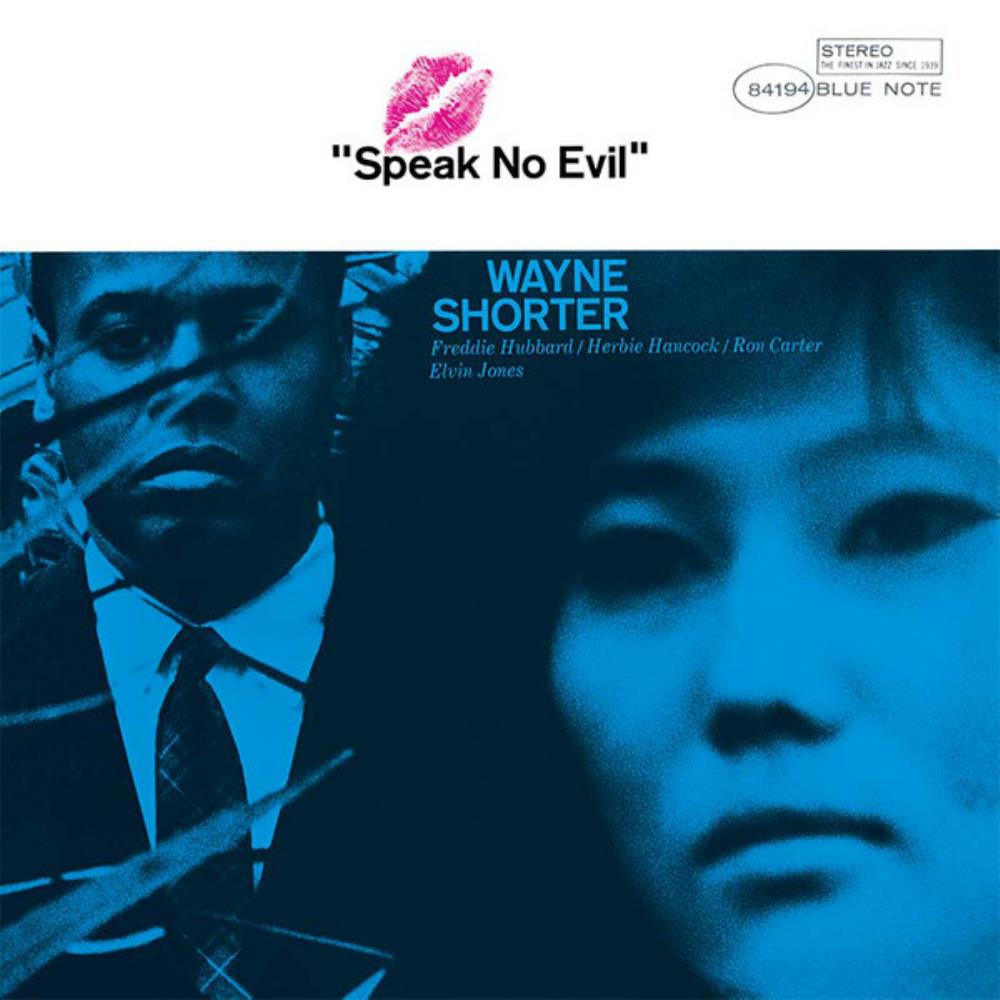

The tribute event was organized by the Arts + Literature Lab and it covers a discerning array of Shorter’s remarkable oeuvre. It opens with “Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum,” one of the uncannily fetching tunes from his masterpiece album of the 1960s, Speak No Evil.

Wayne Shorter’s 1964 acoustic jazz masterpiece, “Speak No Evil.” Bing images

The title admonishment doesn’t mean that Shorter did not fearlessly peer into the eyes of evil and transmute that into music, among his other uncanny feats. Besides the implicit ominousness of that fable-evoking tune, that shadow-toned album includes the pieces “Dance Cadaverous” and “Witch Hunt,” although one suspects Shorter, a Buddhist fascinated with science fiction, was far more intrigued than put off by the “evil” powers of witches. Tenor saxophonist Pawal Benjamin, employing Shorter’s own horn voice, dug into hearty low notes in a solo both meaty and muscular, though not as oblique as Shorter’s would be. Pianist Dave Stoler came in swinging with some Herbie Hancock-like harmonies. The only drawback here was a rather ragged ensemble reading of the theme.

But that cleaned up in the playing of the ensuing tune, “Lost,” from an underappreciated Blue Note album The Soothsayer. Stoler plays tough here, riding the changes with block chords, really digging into this minor-key mood. As with the first tune, “Lost” has marvelously dense but resounding harmony in the ensemble line, rendering it indelible to memory.

The front line of the Wayne Shorter tribute band included (L-R) trumpeter Russ Johnson, tenor saxophonist Pawal Benjamin, and alto saxophonist Clay Lyons.

The band ensues with their own take on “Nefertiti,” recorded with the Miles Davis Quintet. The original was atypical in that it repeats the sighing, languid theme over and over, with no front-line solos, only drummer Tony Williams sustaining the tune with an explosive solo throughout, so you are constantly listening to his drumming as the theme turns mantra-like. Here the band allowed for a Benjamin tenor solo that slices up the theme nicely while drummer Wayne Saltzman digs into the Williams-esque rock-shuffle feel while striving to approximate the incendiary energy of a drummer who made legend of himself with Miles Davis even in his late teens.

Here Stoler also delivers very Hancock-like block chords and octaves, tart and pungent but still pretty, a fine-honed power.

The ensuing tune, “The Big Push,” also from The Soothsayer, has harmonies I could eat for dinner, as protein-packed as they are, and another oddly engaging melody. About Shorter’s harmonies: Each has a story-telling quality, with a layered ensemble chord a chiaroscuroed image in itself, and the change sequences cast suspense and weird beauty in equal measure.

I’ll touch on the second set somewhat more briefly: a highlight was Shorter’s intense yet atmospheric “Sanctuary,” written for Miles Davis’s slightly satanic yet spiritual album of controversial jazz fusion, Bitches Brew from 1970. It has a loping, free-ish melancholy contour, and here trumpeter Russ Johnson shone — the style is his wheelhouse, unfettered but well-formed improv.

Tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter with trumpeter Miles Davis in the band that produced “Sanctuary,” from the seminal jazz fusion album “Bitches Brew,” which included bassist Dave Holland and drummer Jack DeJohnette. Courtesy www.musicajazz.it/festival-e-concerti

The band then shifted back to the Shorter Blue Notes with “El Gaucho,” another deceptively simple theme from the album Adam’s Apple with a characteristically resonating harmonic structure.

The band encores with, for Shorter, comparative ear candy. The rollicking “Yes or No” is among the composer’s most ingratiating and invigorating melodies and saxophonist Benjamin is cooking the hard-bop brew here, which could have been a Jazz Messengers tune, from Shorter’s days as musical director of that band. But the title’s implicit dialectic is key; this is from the album JuJu, by which time Shorter’s was conceptually delving into paradoxical African powers beyond the ordinary.

Such tension-filled qualities permeated the musical particulars of his writing and soloing style and helped to sustain the intrigue of several generations of jazz musicians as represented here.

So, this critical preview is to help document what you hear but, most of all, to encourage you to sit down, buckle up in the safari jeep, and follow this band longer than you might otherwise, on this Shorter sojourn:

(16) Tribute to Wayne Shorter at Cafe CODA – YouTube

________________