Jazz singer Jessie Hauck performs with two other key members of “Milwaukee Jazz” history, saxophonist Berkeley Fudge and guitarist Many Ellis. Courtesy Wisconsin Conservatory of Music

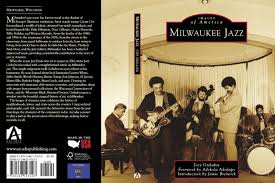

Book review: Milwaukee Jazz by Joey Grihalva, Arcadia Publishing $21.99

This illustrated history lives and breathes with its images, almost literally. The profusion of photos, from the 1920s to the present, lets you see horn players blowing fire, drummers thrashing and paradiddling, and singers wailing the blues. Milwaukee Jazz jump-starts the memories of anyone who lived through even some of the city’s remarkable jazz creativity. For young readers or non-Milwaukeeans, it should be revelatory. It’s loads of fun, but also significant in several ways.

Milwaukee Jazz, part of Arcadia Publishing’s Images of America series, helps substantially to correct a widespread impression. Milwaukee is considered a jazz backwater in many larger cities, most conspicuously Chicago, with which Milwaukee has, well, a complicated relationship. And yet, among the numerous illustrated gems in the book is the ironic tidbit that Herbie Hancock, arguably Chicago’s most famous pianist, got his first professional gig up the dusty country road here in Polka City.

Front and back cover of “Milwaukee Jazz,” Photo courtesy WCM

Having closely covered Milwaukee arts during what author Joey Grihalva appropriately calls a “jazz Renaissance” in the 1980s, I see that scene as reflecting Milwaukee as an archetypal American city. It is the essence of the urban heartland (more on that later) And this notion helps us understand why, without much fanfare, most any other medium-to-large-sized American city has its own distinctive jazz scene, Madison being another example I can attest, to first hand. 1

So let’s dive into some of the images and memories vibrating through this almost effortlessly digestible book.

Do you remember, or know, that Duke Ellington seemed enchanted (as you see here) by Milwaukee entertainer and nightclub owner Minette Wilson, better known as “Satin Doll,” for whom he wrote and named one of his most famous tunes?

Duke Ellington (center) makes the jazz scene in Milwaukee which includes (directly below him) a possible muse, entertainer/club owner Minette “Satin Doll” Wilson. Courtesy Wisconsin Black Historical Society

In far less exalted terms, by the late 1950s the jazz club The Brass Rail “had primarily become a strip club with local musicians providing the soundtrack. This was true of most of the Mafia-owned venues downtown, of which there were many,” Grihalva writes. So, Milwaukee musicians did what they needed to make a living. We later learn that, in 1959, Brass Rail owner Izzy Pogrob was almost certainly murdered by the mob for stealing a boxcar of their alcohol (probably illegally obtained to begin with).Thus, the shadows of this quintessential American city’s deeply ethnic-immigrant grain reveal themselves. Italian and other ethnic club owners did help sustain the music, though too often musicians went poorly paid, despite a musicians union.

By contrast, among the happiest stories is that of Al Jarreau, who grew up on E. Reservoir Avenue, developed in local clubs, and became a multi-Grammy winning vocalist with a chameleon-like stylistic and tonal latitude. But here we learn that Al’s father played the musical saw – with award-winning virtuosity. One infers from this information that young Al may have developed his almost bi-tonal singing ear by absorbing his father’s wowing, sing-song saw!

Jarreau return to “sweet home Milwaukee” frequently and lent his name to a scholarship at his alma mater, Lincoln High, before dying in 2017 at 76.

The city has also attracted great talents from elsewhere including, in modern times, pianist-vibist Buddy Montgomery from the famous musical family from Indianapolis, including his more-celebrated brother guitarist Wes Montgomery. Another Indianapolis transplant, organist Melvin Rhyne, and Montgomery became important figures in Milwaukee, by force of their prodigious talent, ability to develop young sidemen, and for Montgomery forming the Milwaukee Jazz Alliance to advance the interests of local musicians.

Another great musician, from Minneapolis, who grew up here (with local guitarist Manty Ellis as a sort of brother figure) was bop alto saxophonist Frank Morgan. He had a promising career snuffed by a 30-year drug bust jail term, but Morgan returned in the 1980s to international acclaim as an elder jazz statesman.

Alto saxophonist Frank Morgan (here with pianist George Cables) grew up in Milwaukee and, after decades of jail time for a drug bust, his career revived in the ’80s and ’90s to great acclaim. Courtesy Pat Robinson

As early as the 1920s, Georgia-born trumpeter Jabbo Smith was considered a rival to Louis Armstrong in traditional jazz. In the 1930s, he moved to Milwaukee where he stayed for decades, perhaps experiencing, even as a black musician, the city’s well-known bonhomie.

One of the city’s greatest native-born instrumental talents was also marketed as a rival to another more famous musician. Grihalva does this story justice, with four pages devoted to pianist/bandleader Sig Millonzi. Capitol Records signed him in the mid-’50s, hoping to market him as the “American Oscar Peterson.” Millonzi didn’t quite see himself as a version of someone else, so his national recording career was short-lived. But he dominated the Milwaukee scene in the ’50s and ’60s.with his legendary trio and his big band, which would become the Jack Carr-Ron DeVillers Big Band, after Millonzi’s death.

Celebrated Milwaukee jazz pianist and inter-racial pioneer Sig Millonzi leads his big band at Club Garibaldi in Bay View, where the group played every Monday night from 1975 until Millonzi’s death in 1977. Courtesy Stacy Vojvodich

This great Italian-American musician also contributes to one of the most important stories coursing through Milwaukee Jazz – the sometimes delicate but compelling saga of race relations in what remains one of America’s most racially fraught and segregated cities (partly due to its peculiar geography).

Grihalva reports that, in the 1920s, “the hottest (jazz) rooms were in the black neighborhood of Bronzeville. Located just north of downtown, most Bronzeville clubs were known as ‘black and tan’ because they welcomed both black and white patrons.” And yet, in 1924, black musicians in Milwaukee had to form their own union after being excluded from the local American Federation of musicians union.

This history is another reason why Milwaukee is an archetypal American city, as a microcosm of our nation’s troubles, complexities and sins. America’s indigenous musical art form, forged largely by descendants of African-American slaves, was embraced by various ethnic groups, which eventually led to crossing color lines. Millonzi recorded with black jazz entertainer Scat Johnson (who begat two talented musical sons) and Millonzi later became a big local draw at Summerfest performing with Berkeley Fudge and Manty Ellis, two leading local black players.

Another integrative exemplar was virtuoso Milwaukee guitarist George Pritchett, a somewhat irascible character who, perhaps because of his willfulness, consistently employed black rhythm section players, including drummer Baltimore Bordeaux, “integrating otherwise all-white south side bars and clubs.”

Actual integration of local bands reaches back at least to the 1940s. A Milwaukee Jazz photo shows black and white musicians from that period jamming, including Jewish saxophonist Joe Aaron and (possibly) black local singer-pianist Claude Dorsey.

Black and white Milwaukee musicians from the 1940s jam, including Jewish saxophonist Joe Aaron (center) and possibly black singer-pianist Claude Dorsey (left). Courtesy Rick Aaron

Of course, the mythology, and often the practicality, of the jazz life told young, ambitious musicians to eventually test their mettle in New York or Chicago. So inevitably this city lost major talent, such as saxophonist Bunky Green and pianist Willie Pickens to the Windy City.

Then something happened in the early 1980s – Milwaukee’s “jazz renaissance.” Several important inner city clubs played a role, including Brothers Lounge, Space Lounge and The Main Event. But two crucial entities arose in synchronicity. In 1978, Chicago community organizer and amateur musician Chuck LaPaglia opened the Milwaukee Jazz Gallery on Center Street and – with his strong Chicago connections – got his ambitiously fledgling club on the touring circuit for national jazz performers.

The club location, in Milwaukee’s Riverwest neighborhood, on a direct artery into the inner city, facilitated integrated audiences and LaPaglia booked national acts several weekends a month, and filled out his calendar with an eclectic array of Chicago and Milwaukee performing arts talent.

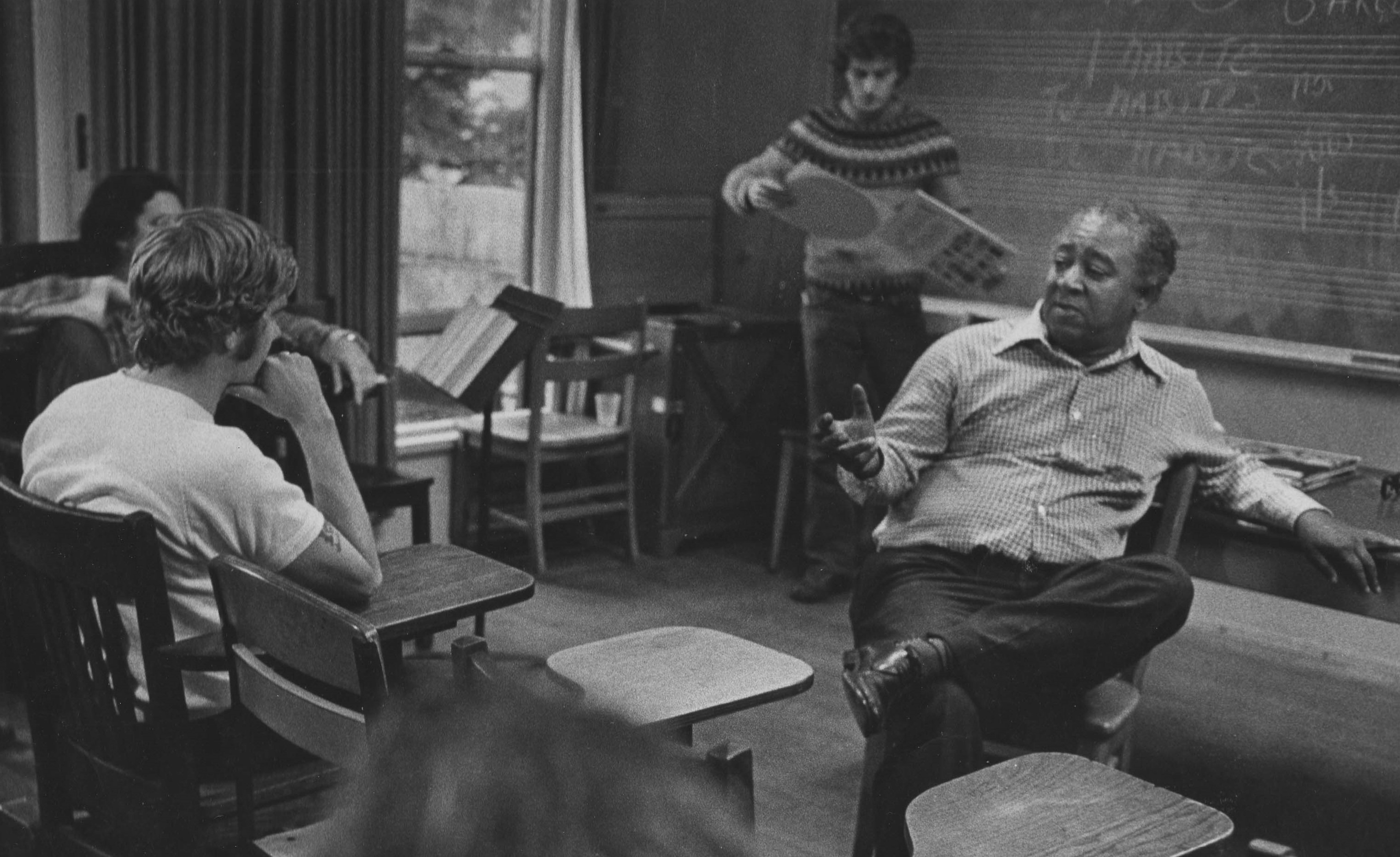

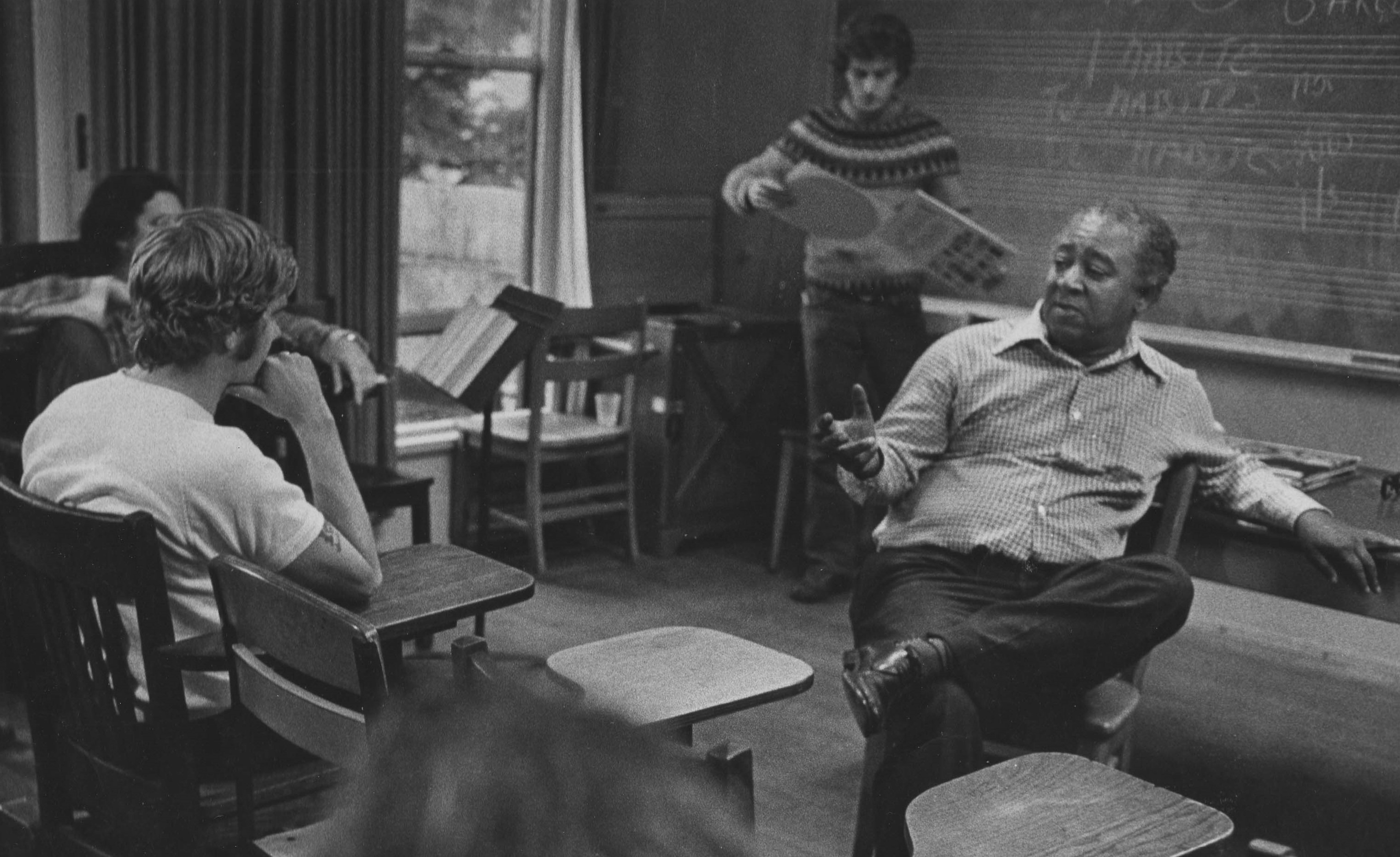

Concurrently, The Wisconsin Conservatory of Music had established a jazz degree program (focusing on small combos unlike most jazz ed) led by Milwaukee guitarist Manty Ellis and pianist-educator-mentor Tony King. Avuncular and oracular, he was a harmonic genius, emerging from the tradition of Earl “Fatha” Hines. King traversed the bridge from early to modern jazz theory. His hunger for knowledge arose from “the Jim Crow segregation he endured as a child in southern Illinois.” King, Ellis and others, like saxophonist Fudge and Chicago pianist Eddie Baker, helped mold the school’s burgeoning baby boomer/Gen X breed of players.

The Wisconsin Conservatory of Music’s Tony King (right) instructed and inspired students and co-founded the school’s important jazz degree program. Courtesy WCM.

Crucially, these young musicians had the chance to intimately see and work with world-class musicians at the Milwaukee Jazz Gallery, including Milt Jackson, Dexter Gordon, Chet Baker, Dave Holland, Henry Threadgill, Anthony Braxton, Muhal Richard Abrams, Betty Carter, The Monk-alumnus band Sphere, Art Blakey and the Marsalis brothers. Summerfest already had a big-name Jazz Oasis.

Yes, the music coursed through the thick, nocturnal city air with a darkly swinging pulse, as an ongoing alternative to disco and pop-rock. Dedicated disc jockeys like drive-timer Howard Austin and all-night jazz guru Ron Cuzner fed the real jazz thing into local airwaves and perhaps the subconsciousness of those sleeping to Cuzner’s music, “in my solitude.” On the Milwaukee River, it flowed too, through a riverfront jazz club in the up-the-Mississippi tradition, and on the East Side at the Jazz Estate.

Local record stores stocked the Savoy, Blue Note, Prestige, and Impulse labels and then, Afro-electric Miles Davis (!). A multi-venue Kool Jazz Festival with jazz superstars, from Sarah Vaughan to Ornette Coleman, came to town in 1982. Grihalva also rightly notes the jazz influence on the city’s internationally renowned punk-folk rock band, The Violent Femmes, which emerged during this renaissance. Newer Milwaukee groups like Foreign Goods work the crossroads of jazz, hip-hop and R&B.

Grammy-winning trumpeter Brian Lynch (pictured below as a WCM music student) who later joined Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, pianists David Hazeltine and Rick Germanson, bassists Gerald Cannon and Billy Johnson, drummers Carl Allen and Mark Johnson and others arose to national success from this northern gumbo of old and new jazz tradition – “paying dues” in jam sessions and for-the-door gigs, and the higher education standards that the lucrative big-band era begat modern jazz in high schools and colleges around the country.

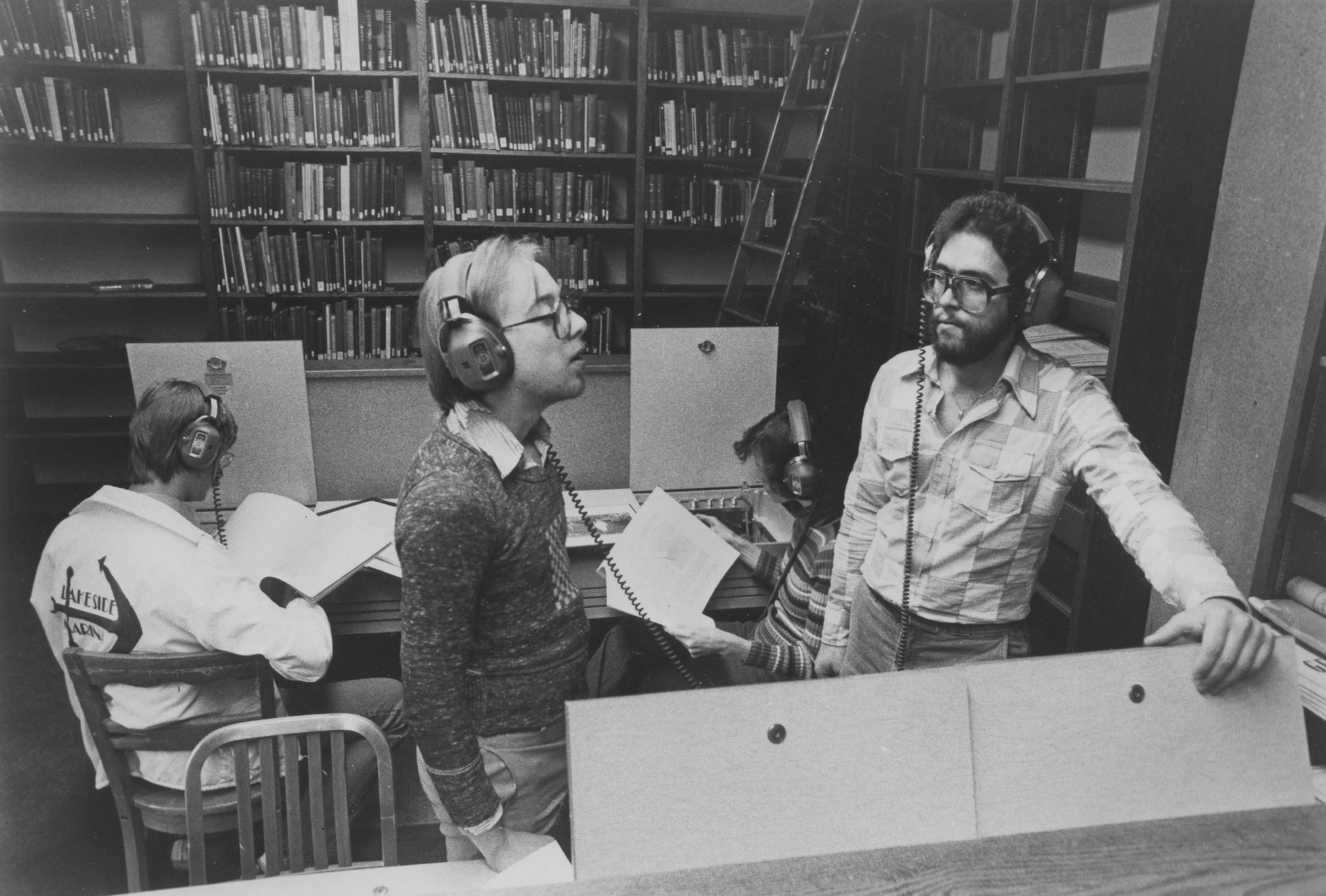

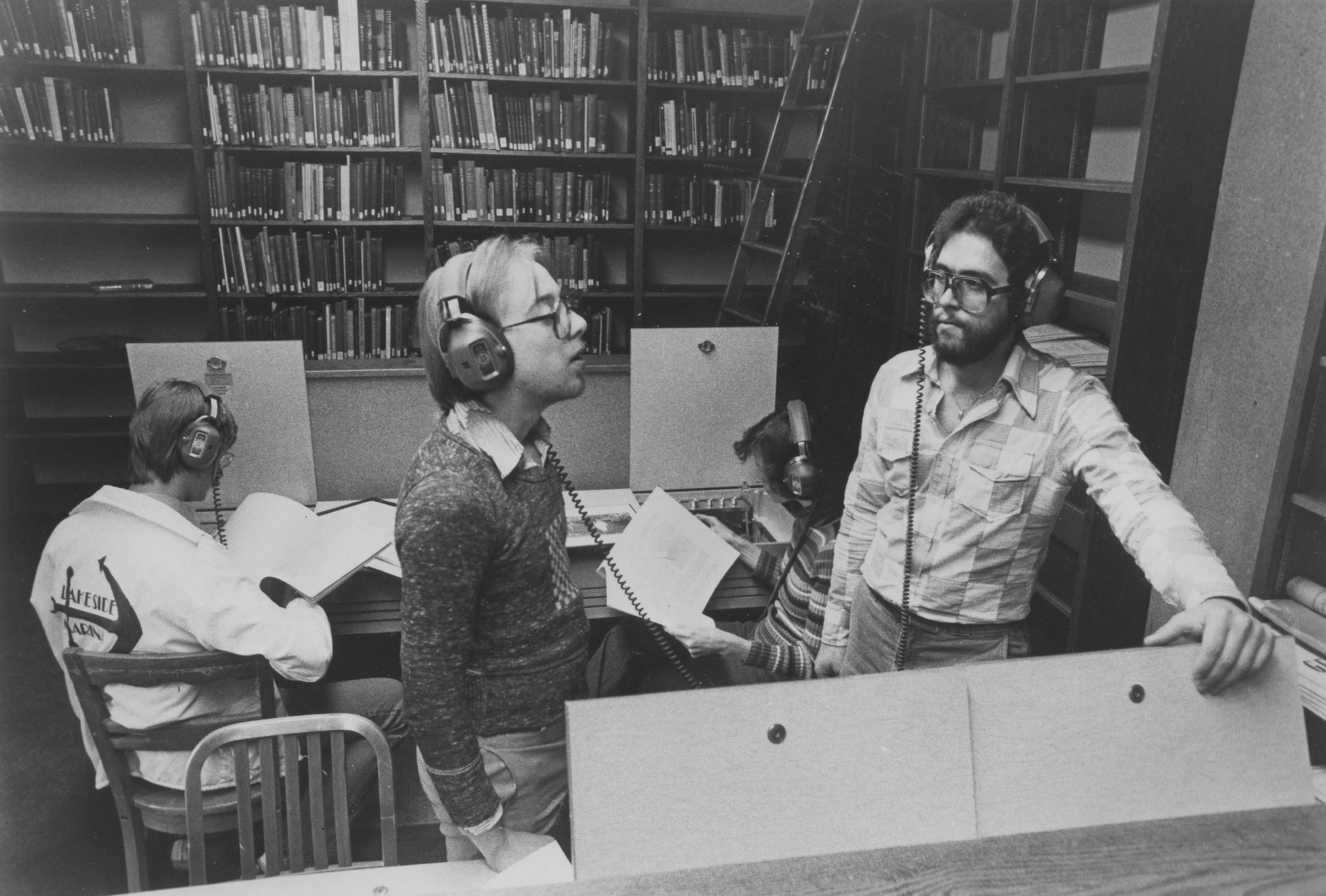

Trumpeter Brian Lynch (left) auditions music with another student in the Wisconsin Conservatory listening room in the early 1980s. Lynch’s auspicious career has since included two Grammy Awards. Courtesy Joey Grihalva and WCM.

Wisconsin Conservatory alumnus Lynch, now a music professor at the University of Miami, exemplifies the history-conscious American jazz artist, passing the music forward. This extensively-honored musician is capable of transmitting and embodying the music’s glory and its ghosts, having authored tribute albums to unsung trumpeters and, most recently, Madera Latino, a magnificent Latin-jazz interpretation of the music of Woody Shaw, an electrifying and advanced post-bop trumpeter who died before his time, under tragic circumstances. Lynch also frequently returns to Milwaukee for student workshops and concerts. A younger Milwaukee-area jazz trumpeter-educator-advocate with admirable historical perspective is Jamie Breiwick, who provided the book’s introduction.

As a historical writer, Grihalva is comparatively young, but dedicated, and he has done smart and diligent research to create this book. There are some notable omissions, such as the utterly original avant-garde bands Matrix 2 and especially the brilliant What On Earth? (identified in passing as a jazz-fusion group). Also one must note important 1970s jazz-fusion groups like Sweetbottom, which produced progressive fusion guitarist Daryl Stuermer – of Genesis, Jean-Luc Ponty-George Duke fame – and Street Life, the Warren Wiegratz-led house band for The Milwaukee Bucks for years. Reed wizard Wiegratz now works often with an award-winning Latin-jazz fusion band VIVO. Nor can we forget the stellar ensemble Opus, which remains active, educating and recording, with its original personnel.

And for the book’s panoply of artists and jazz-scene builders, Arcadia should’ve provided an index.

America, and the world, suffer profoundly today for having forgotten the wonders, complexities, and tragedies – the hard lessons of the 20th century. Yet, some of the best of the century was jazz, here, there and everywhere, now a global art form of the improviser-composer in a blues-based language, or freely spun ones. Celebrate and support it wherever you live. And best of all, hear it live, with friends, especially in a time when our sense of community has splintered radically, increasingly abstracted into “sharing” on miniature electronic devices. Jazz remains doggedly, a lifeblood of humane and democratic art, a music of tradition and liberation.

Especially in such a decreasingly literate age, image-rich Milwaukee Jazz is a vibrant document for any jazz lover, or music lover with open ears. It brings to mind the idea of American novelist William Faulkner, a quote adapted by Barack Obama in his “A More Perfect Union” speech: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

______

Milwaukee Jazz is available at local bookstores, and from www.arcadia publishing.com To purchase a copy autographed by the author, visit http://www.mkejazzbook.com

Book signing events will be held Friday, October 11, at the Wisconsin Black Historical Society. Another event is tentatively planned for September in Sherman Park with the Manty Ellis Trio. Details coming soon.

Grihalva also plans an online e-supplement to the book, with more photos, and written contributions from others, including this writer.

- 1 I explore this idea of Milwaukee as an archetypal American city in greater depth in my forthcoming book Voices in the River: The Jazz Message to Democracy.

- 2 Milwaukee’s jazz-classical-rock band Matrix should not be confused with the same-named fusion horn band from Appleton, which became recording artists for RCA in the 1970s. An original member of that Appleton group has recently blessed Wisconsin music history with the book Wisconsin Riffs: Jazz Profiles from the Heartland, a fairly comprehensive history of Wisconsin jazz musicians by Appleton educator-musician Kurt Dietrich. He’s the father of a gifted jazz orchestra leader/composer.arranger based in Madison, Paul Dietrich, who recently released a brilliant debut orchestra album.

Like this:

Like Loading...