Lynne Arriale has traveled a long ways since she left her hometown of Milwaukee. When she returns to Wisconsin for concerts in Madison and Milwaukee, it will be as a brilliantly mature pianist and composer whose music has grown and evolved into something profoundly attuned to social and political conditions of our time.

The Lynne Arriale Trio, with John Christensen on bass and Mitch Shiner on drums, will perform Saturday, April 2 at Café CODA, 1224 Williamson St., in Madison, at 7 and 9 p.m. Tickets are $25 per show. For information, visit https://cafecoda.club/.

Then, the trio performs in Milwaukee on Sunday, April 3 at The Jazz Estate, 2423 N. Murray Ave., at 7 p.m. Tickets are $20-$27. For information, visit https://jazzestate.com/.

Finally, Arriale will perform a master class on Monday, April 4 from 6 to 8 p.m. at The Helen Bader Recital Hall, of the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music, 1584 N Prospect Ave, Milwaukee. The class is free and open to the public. For more information, visit https://www.wcmusic.org/concerts-events/master-class-series/ or https://fb.me/e/2k1sFSB4C

Always a fabulous musician, since winning the 1993 international great American jazz piano competition, she has come to realize the confluence of art and life, for its better and worse.

But before addressing her mature artistry further, I’ll suggest it’s probably too easy for those from a musician’s hometown to always think of her as “our musical daughter,” and never realize the scope of the artist’s accomplishments and acclaim. Jazz Police’s declaration of her as “the Poet Laureate of her generation” may sound a tad high-falutin’ for hometown folk. Yet, in a still culturally under-recognized city, we might take pride in a native’s success where we can get it. Arriale’s growth derives from her talent and drive, and the vast reach of her world-wide touring, recording and educating experience, accompanied by consistent acclaim.

Her full biography is rather dizzying. Awards and jazz chart-topping among her previous 15 albums aside, one of Arriale’s most distinctive honors was to be the only woman among a gaggle of ten all-star pianists in a tour of Japan titled “100 Golden Fingers,” which included Tommy Flanagan, Hank Jones, Cedar Walton, Kenny Barron, Harold Mabern, Monty Alexander, Roger Kellaway, Junior Mance and Ray Bryant. It’s doubtful that a larger aggregate of distinguished mainstream jazz piano masters has ever toured together. Her musical collaborators include Randy Brecker, George Mraz, Benny Golson, Rufus Reid, Larry Coryell, and Marian McPartland.

Nor has it been all about Arriale the artist; this comparably dedicated educator was the first woman accorded a cover story for the magazine JazzEd. She has conducted master classes and clinics internationally throughout the US, UK, Europe, Canada, Brazil and South Africa. She’s also Professor of Jazz Studies and Director of Small Ensembles at The University of North Florida in Jacksonville.

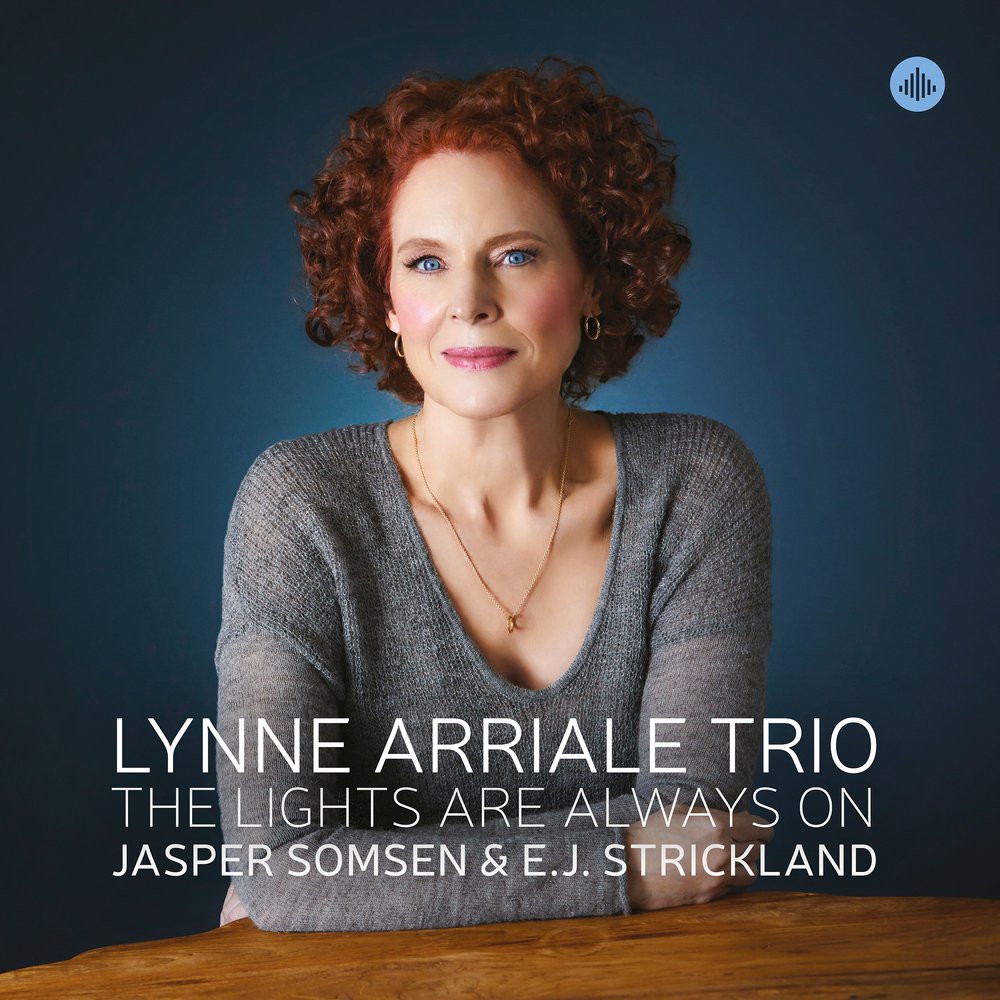

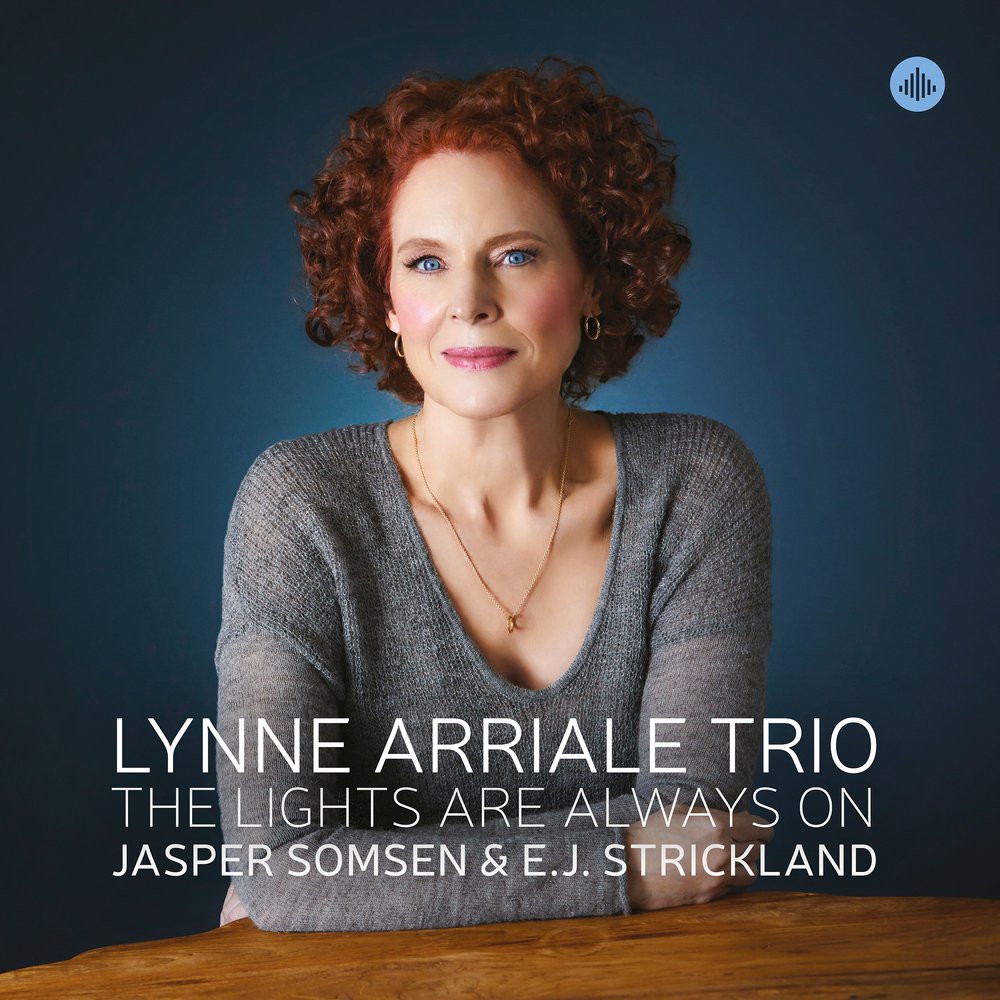

Nevertheless, as much as any pianist of her generation, Arriale has dedicated herself to the distinctive art form of the jazz piano trio, as the late Bill Evans and company came to define it. As demonstrated in her new album The Lights Are Always On, she continues developing her synchronistic relationship with bassist Jasper Somsen, and drummer E.J. Strickland, one of my favorite percussionists of his generation. Yet, like most dedicated touring professional jazz musicians not named Keith Jarrett, she’s also an ace at working with local trio mates, as she’ll do in Wisconsin.

None of which, is to say that, on her own, she’s averse to sometimes enhancing the purity of the trio form. This was evident in stunning fashion in her magnificent previous album Chimes of Freedom. As I wrote at the time, “The title song, by Bob Dylan, and Paul Simon’s ‘American Song,’ both sung by K.J. Denhert, tenderly render portraits of humanity.”

Lynne Arriale. Courtesy JazzTimes

Arriale’s finely attuned and powerful playing and arrangements eloquently expanded upon the implications of those verses by two of our nation’s supreme songwriters. Arriale increasingly reached musical and expressive inroads into the essence of the American experience, in all of its joy and suffering, celebration and loss.

Her new album furthers that quest, while asserting her own vision by composing all the music. The Lights Are Always On is a suite of compositions that reflect the world-wide, life-changing events of the past two years. Several of the pieces nominally honor heroes around the world, including “those who served as caregivers on the front lines of the COVID pandemic and as defenders of democracy,” amid the crisis of the last five years, and the Jan. 6 Capitol mob insurrection.

In the liner notes, Arriale explains the pointed and poignant meaning behind the title tune:

“This collection was inspired by the doctor and all front-line health care workers,” she says. “For me, Dr. (Prakash) Gada, (an esophageal and robotic surgeon in Tacoma, Washington) crystallized the workers’ sense of mission during

this extraordinarily challenging time. He said, ‘Here I am back at work after

COVID…I fled Kuwait after the invasion. No matter what happens, no one works

at home. The lights are always on. Babies are being born; bones are being set.

This hospital, this profession…we are in a league of our own; we’ll take care of you,

I promise. I stand next to the most fearless people I have ever seen.’ ”

The title tune coveys care and tenderness in Arriale’s delicate yet forthright phrasing and, as the piece develops into rising phrases and searching tonalities, a measure of dedication and courage, and the “better angels of our nature,” which she still believes in. The tune is brief, as in a dedication.

The album opener “March On,” evokes dogged determination in a steady sequence of minor Tyner-esque chording, as in the steady, tireless dedication of protest marchers for justice in America and worldwide. “notably in the 2017 Women’s March on Washington and those marching to protest the murder of George Floyd.” writes album annotator Lawrence Abrams.

Similarly spirited, “Sisters” is a feel-good, gospel-tinged aria for the advancement of women’s rights and equality, an anthemic statement of full-throated chords, octaves, and shining linear pronouncements, all riding Strickland’s groove-splashing cymbals.

Honor” alludes to Col. Alexander Vindman’s extraordinary courage and righteousness as a witness addressing the impeachment hearings “regarding Donald Trump’s scheme to withhold congressionally approved foreign aid to Ukraine, and thereby extort from that country a sham investigation of Trump’s rivals,” Abrams writes.

Somson’s bass solo seems to evoke the National Security expert’s very personal dedication to his father, who led him to emigrate from Russia forty years ago. Vindman’s story is all the more pointed amid the current Russian attack on Ukraine, after Trump’s weird “bromance” with Vladimir Putin. We know too, that Vindman was fired by Trump for his honesty.

Here and throughout the album, Arriale’s soloing is concise and emotionally to the point, as a performing composer, never lapsing into mere virtuosic display.

“Into the Breach” addresses the Capitol Police who braved the Jan. 6 mob trying to stop the certification of Joe Biden’s presidency win. Arriale doesn’t try to dramatically evoke the chaos, rather again focusing on the heroes, and the sense of dedicated bravery. Her chords and phrases halfway through reach into the upper register, suggesting rising blood pressure and stress. Again, a bass solo allows for thoughtful breathing room, while sustaining the urgency. “Into the Breach” conveys a grave almost Zen-like serenity, which may engender such courage, in the face of overwhelming danger.

The album also features “The Notorious RBG,” a dedication to the pioneering Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Especially memorable is the penultimate tune “Walk in My Shoes,” dedicated to the late Rep. John Lewis. The fairly chromatic dissonance of the chording conveys a masculine righteousness, steely passion and dignity — the essence of the spirit of this bloodied demonstrator in the Civil Rights era in the racist South, followed by a distinguished career as an eloquent firebrand for justice in Congress. I even like the way the tune fades out at the end, as if, even in Lewis’ passing, his spirit may come back, around the bend someday, in some form.

Like this:

Like Loading...