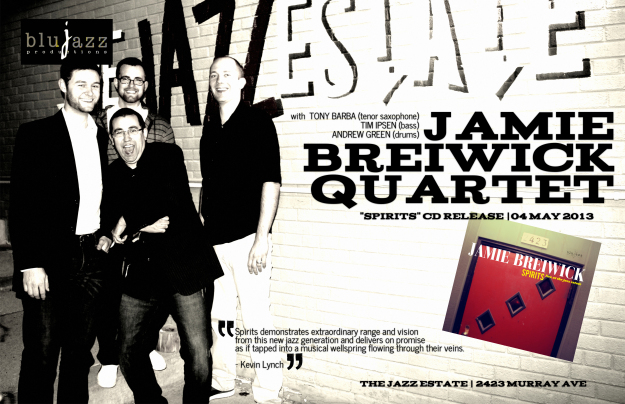

The Milwaukee jazz quartet Heirloom performed an album release concert at The Estate recently. Photo by Kevin Lynch

For a jazz club to survive since 1977, especially in Milwaukee, you’d

have to think it just might be haunted by cats, as in a place of nine lives,

where a tail may sway or wiggle, but typically swings and sometimes

even forms an S curve, akin to Miles Davis’s famous posture while

soloing.

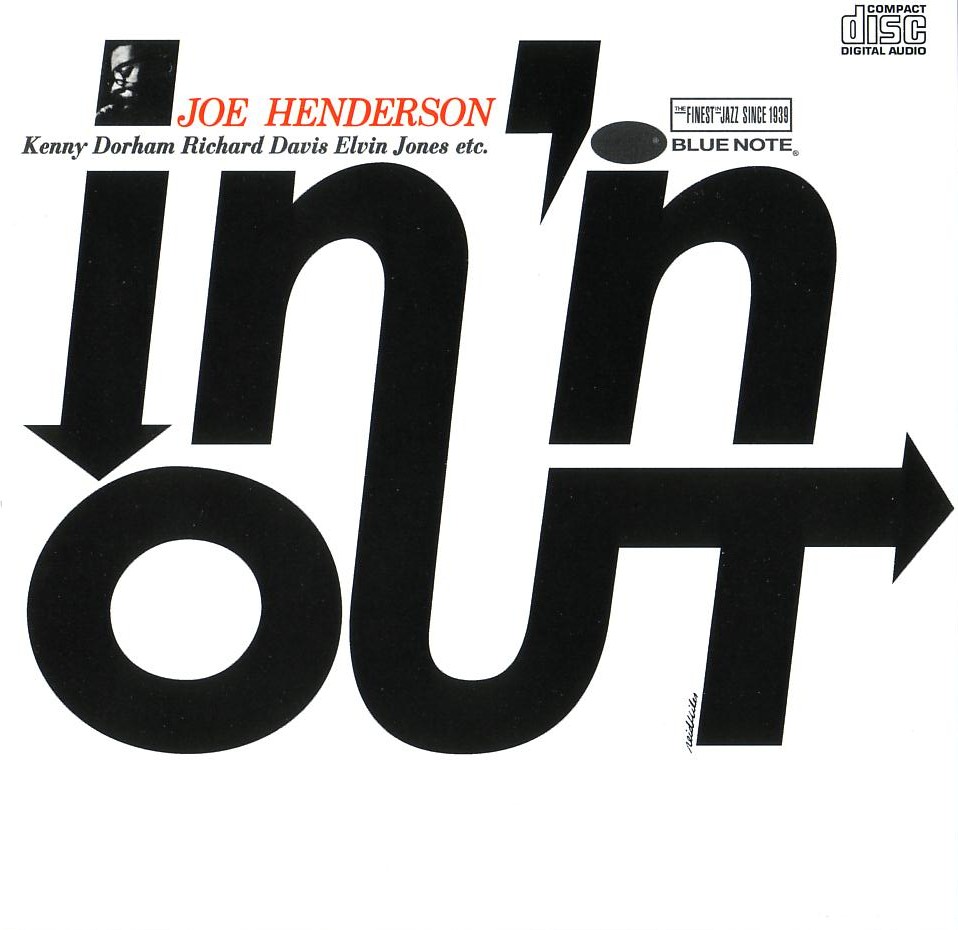

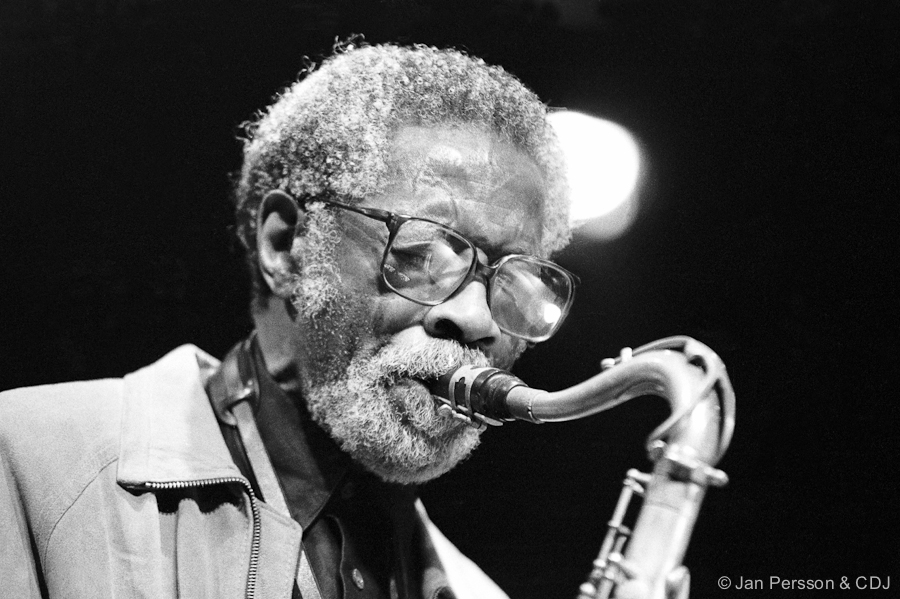

The Estate (a.k.a The Jazz Estate) has never been blessed with Miles

in person. But jazz, America’s indigenous art form, is now a long, strong

international language spoken by many practitioners, including such

famous Estate performers as Joe Henderson, Tom Harrell, The Bad

Plus, Harry Connick Jr., Cedar Walton, Eddie Gomez and Little Jimmy

Scott, and Milwaukee-bred stars like Brian Lynch, Lynne Arriale, and

David Hazeltine, among others.

Cat ‘tails are a serious theme here, as current owner John Dye has

transformed the joint into one the city’s most sophisticated cocktail

hangouts, befitting hip culture, jazz or no jazz.

So the music has faded into the club’s ether several times over the

years. But give this city some props for helping to revive venue’s music.

There are reasons why local jazz singer Jerry Grillo has made

Milwaukee his own in a celebrated recorded anthem titled “My

Hometown, Milwaukee” just as he’s made The Estate his artistic and

cocktailed home away from home. The song won a 2023 WAMI Award

for “Most Unique Song” and a mayoral proclamation for “Milwaukee

Day” in May of 2022. The mayor helped cement the venue’s reputation

in Milwaukee lore, at least obliquely, like the proverbial cat standing slyly

in the bandstand shadows. Grillo’s song is colorfully celebratory and

self-deprecating, again, pure Milwaukee.

Jazz singer Jerry Grillo adds drama to one of his many performances over the years at his “home” club, The Estate. The singer will perform a Christmas show at The Estate on December 5. Photo courtesy jerrygrillo.com

In other words, this town has a still-underapprecated modern legacy of

jazz performance and radio. Think of the indomitable and peripatetic dejay Ron Cuzner, WHAD’s Michael Hanson, or WMSE’s Jim

Glynn and Dr. Sushi, or Howard Austin and WYMS programming in the

1980s and ’90s. They all helped sustain jazz consciousness and

lifebood for the sake of live events, which Cuzner frequently emceed

during his many years as the city’s pied piper of airwaves jazz. The

community of jazz that has sustained the local culture over those years

has included, along with The Estate, The Wisconsin Conservatory of

Music, The Milwaukee Jazz Gallery and its offspring, the JGCA, The

Pfister Hotel’s Blu nightclub and Mason Street Grill, Caroline’s Jazz Club, Bar Centro, Transfer Pizzeria Cafe and The Milwaukee Jazz Institute, an exemplary recent education and concertizing organization.

This is all to put one uber-cozy and eccentrically-configured East Side

club in its rightful historical context. The Estate endured nearly

devastating losses during COVID. A small miracle of persistence?

The intimacy and modest size has seemingly put it beyond the

perceived employment of many regional jazz artists who might have

ostensibly outgrown such neighborhood venues, such as renowed

cutting-edge Chicago saxophonist Ken Vandermark, as Dave Cornils

expained recently in an east side coffeeshop. “He told me a lot of

venues don’t invite us,” Cornil relates.

Who’s Dave Cornils? A new cat in town? He’s a 40-ish gatekeeper of

the music, the latest Estate manager and music booker. He’s actually

been a Dye right-hand man, a barkeeper par excellence who had to

memorize the five-to-six hundred drink recipes Dye requires for

Byrant’s, his showcase cocktail lounge. There’s no menu there, so

Cornils had to ask a customer what she likes, read her response and

whirl up a wizard’s brew. Doubtless his improbable acumen at this

weighty task helped Dye decide Cornils had the chops to book good

jazz and related music.

Those duties might actually be easier than all the esoteric mixology, with

some artist website assistance. “It’s been fun, a challenge for a nerdy,

encyclopedic brain,” he says with measured self-regard. How did he get

into jazz? “My parents were not a jazz family. So this was an offshoot of

rebellion. Whatever they didn’t like must be cool. I learned from records

and listening to WMSE, which was like going down a rabbit’s hole. Jazz

there is a bottomless pit, but it also keeps you humble.” Jazz guitarist

Andrew Trim enhanced Cornil’s education when he became a fellow

bartender.

The manager’s formal education and professional background is in

graphic design. “I’ve built up the club’s calender with a rotation of local

performers, a young crop of comers with drive,” he says. Those include

the sparkling quartet Heirloom, which just played the Estate for a

release event for their excellent debut album Familiar Beginnings.

Others include The Erotic Adventures of the Static Chicken and vocalist-

pianist Faith Hatch. Maybe the essence of the place’s straight-ahead

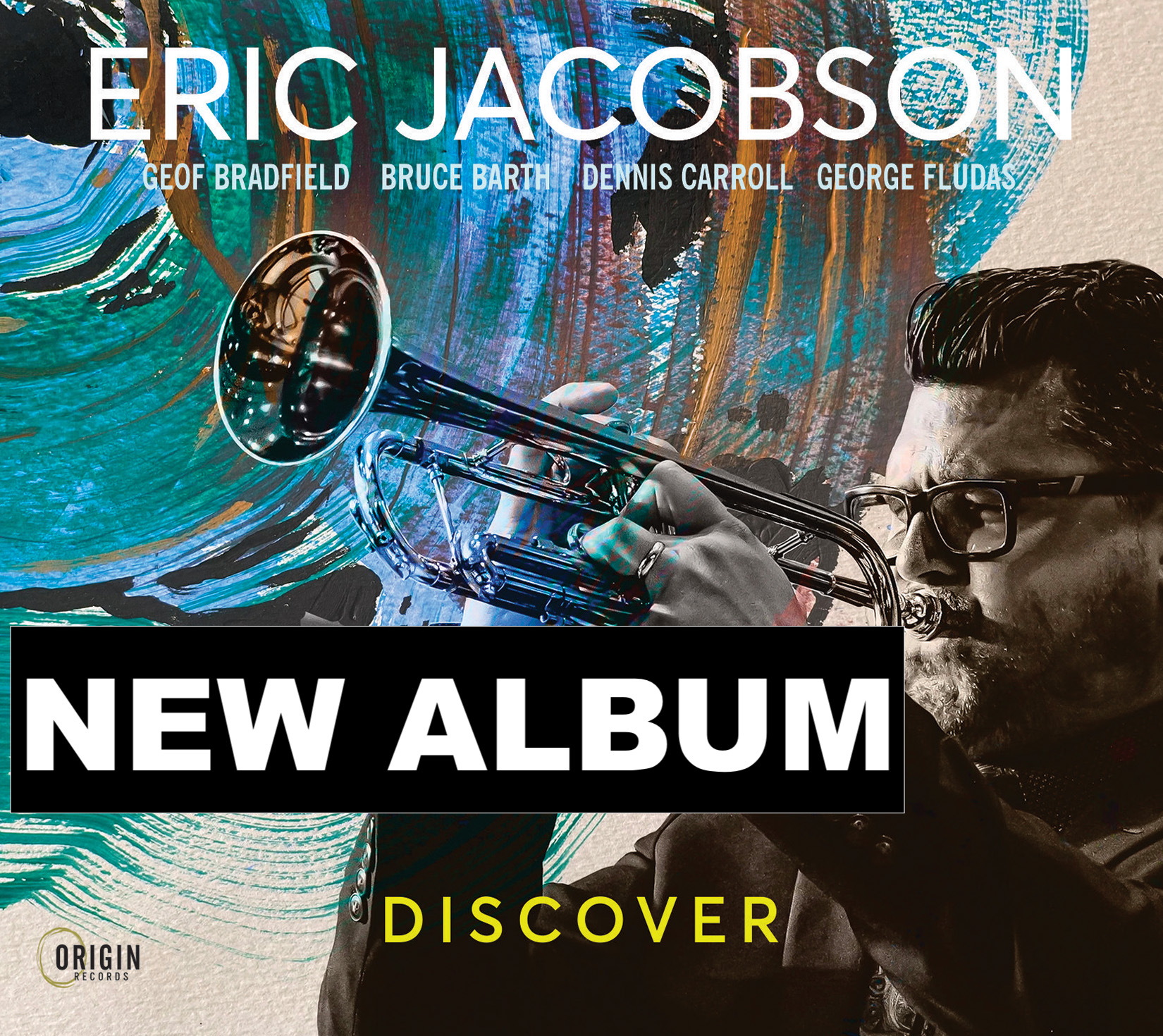

jazz legacy is exemplified currently by virtuoso Milwaukee trumpeter

Eric Jacobson, who performed “Joyspring”: The Music of Clifford Brown”

in early October, inflaming the the historic post-bop fire for the present.

Among compelling out-of-towners on deck include Chicagoans guitarist

and Blue Note recording artist Fareed Haque who returns October 18,

and cornetist Josh Berman on October 10, then acclaimed East Coast saxophonist-

composer Caroline Davis on November 7.

“Berman is aways interesting including the way he moves his body to his music. You can be deaf and know what he’s playing,” Cornils quips.

A stylistic wild card will be Victor DeLorenzo and Friends, on October 25. Milwaukeean DeLorenzo is best known as the original drummer for the renowned jazz-influenced folk-punk band The Violent Femmes.

Even local artists are getting their financial due. A new policy has each

set being a separate show and cover charge. “It’s the only way to to

make enough money for the musicians, given that the place seats 60

maximum.”

The Estate stage and some of its distinctive seating layout.

About a dozen choice seats are ultra-intimate with the stage

— a couple feet away. The majority of audience seating extends in two long wings on each side of the stage, one including the bar. Right behind the close-up seats is a narrow walkway and wall shelf for drinks of standing listeners, and then the

restrooms. So, improbable as it seems, a seat on one of these two

enclosed thrones can provide some of the best music acoustics you’ll

find in town.

If such musical and mixological magic can happen at the Estate, may it

live on forever.

____________

The Estate website, including detailed information on all upcoming music performances, is here: https://www.estatemke.com/

This article was originally published in The Shepherd Express: https://shepherdexpress.com/music/local-music/jazz-is-back-at-the-estate/

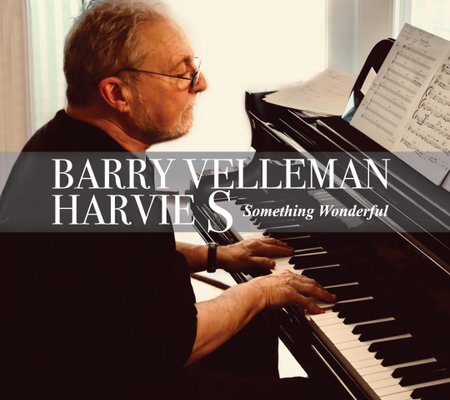

Album review: Barry Velleman/Harvie S. — Something Wonderful (RVS Records)

Album review: Barry Velleman/Harvie S. — Something Wonderful (RVS Records)