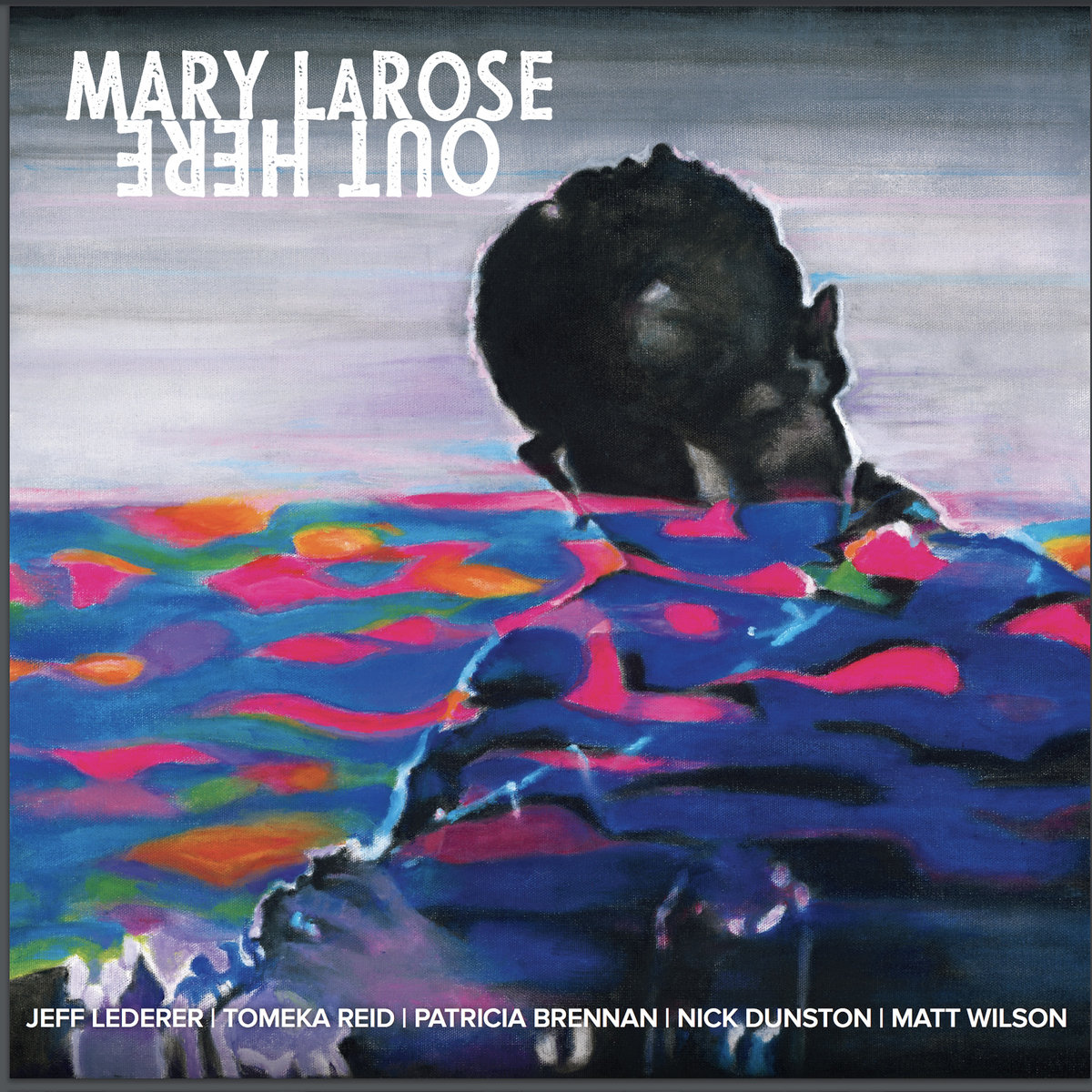

Reviews: Mary LaRose – Out Here (Little i Music), and Out There: Visions of a Sound, jazz portraiture art book by LaRose

Jazz singer/visual artist Mary LaRose embarked on one of the most daring and enlightening projects I’ve heard in a long time. Out Here lovingly reimagines compositions by, an associated with, Eric Dolphy, the supremely gifted multi-instrumentalist who died tragically at 36, in a Berlin hospital, of a diabetic coma after physicians presumed him merely a drugged-out jazzer. 1

LaRose and an excellent quintet resurrect Dolphy. 2 Jeff Lederer’s clarinets superbly evoke Dolphy’s exclamatory, sinuous playing style. Drummer Matt Wilson goes “out there” like a dancing tightrope walker. LaRose ingeniously sets Dolphy’s music to vocalese and scatting. She reveals the meaning of tune “245” — the Carlton Street address in Brooklyn, where many jazz musicians resided. She’s a “fly on the wall” in this hippest of abodes.

She shows that Dolphy’s “Out There” — “You’ve got to push yourself, get out there.” — is cutting-edge but not free jazz, sustained like a gyrating thread of many colors. Her singing lends warm humanity to Dolphy’s wide intervals, his way of releasing, and containing, musical expression. “Music Matador” revels in Dolphy’s underexposed roots in lilting Panamanian rhythms.

“Serene,” is a Zen-like meditation on the sublime relationship between syncopation and relaxation. “Love Me” (a Victor Young standard Dolphy recorded in duet with Madison-based bassist Richard Davis), is here a duet between LaRose and bass clarinetist Lederer, who are married, and they radiate nearly erotic sensual interplay.

Finally, a Mal Waldron tune that Dolphy debuted, “Warm Canto” glows, accompanying LaRose’s poetic ode to death, as strangely moving as anything modern jazz song has produced: “When I am dead, make art of my bones, bleach and dry them in the sun/ pure white, startling as stars…”

LaRose recites these lyrics, in the first person, in a tender yet declamatory tone. She seems to strive to both honor and inhabit Dolphy’s long-passed but ever-present spirit. A vividly-imagined, wholly-personalized evocation of the man and the artist.

Give thanks that time has allowed her, and the sun Out Here, to rise and shine on his legacy, to lengthen it to more proper fulfillment.

This album review Was lowercaseriginally Published in the Shepherd Express in slightly shorter form:https://shepherdexpress.com/music/album-reviews/out-here-by-mary-larose-little-i-music/

***

Jazz singer-songwriter-artist Mary LaRose in her studio, where she produced the art for her new book “Out There.” Courtesy Jazz Times

During LaRose’s period of this creativity, largely the pandemic, she produced far more than just a great album of music. She is also an accomplished visual artist, who studied with the famous realist painter Philip Pearlstein. She has also published, in conjunction with the album Out Here, a book of her portraits of jazz saxophonist’s, titled Out There: Visions of a Sound, (the main title is also the title of a well-known Eric Dolphy album).

The book is a limited edition of 100 copies, and at least as comparable an accomplishment as the album, in its own way. It’s one of the finest collections of jazz portraiture artwork I’ve seen, given that jazz portraits are far better-known in photography. 3 How many people can say they transmuted the year of the plague into so much quality productivity?

LaRose consciously chose to set her work apart from jazz photography by not basing her portraits on photographs, but rather on videos of the musicians. That way, she could strive to capture more of the dynamic essence of the musician, without venturing far beyond her realistic discipline. Rather than hard-edged realism, she uses pastel crayons on black paper to highly evocative effect, on all of the portraits except for the color cover portrait of Dolphy, which is oil on canvas, and also the cover of the album.

That painting is much more of a painterly exercise, with dancing red tones around Dolphy and his flute, which seems to evoke, and perhaps defy, Dolphy’s famous quote, “When you hear music, after it’s over, it’s gone in the air; you can never recapture it.”

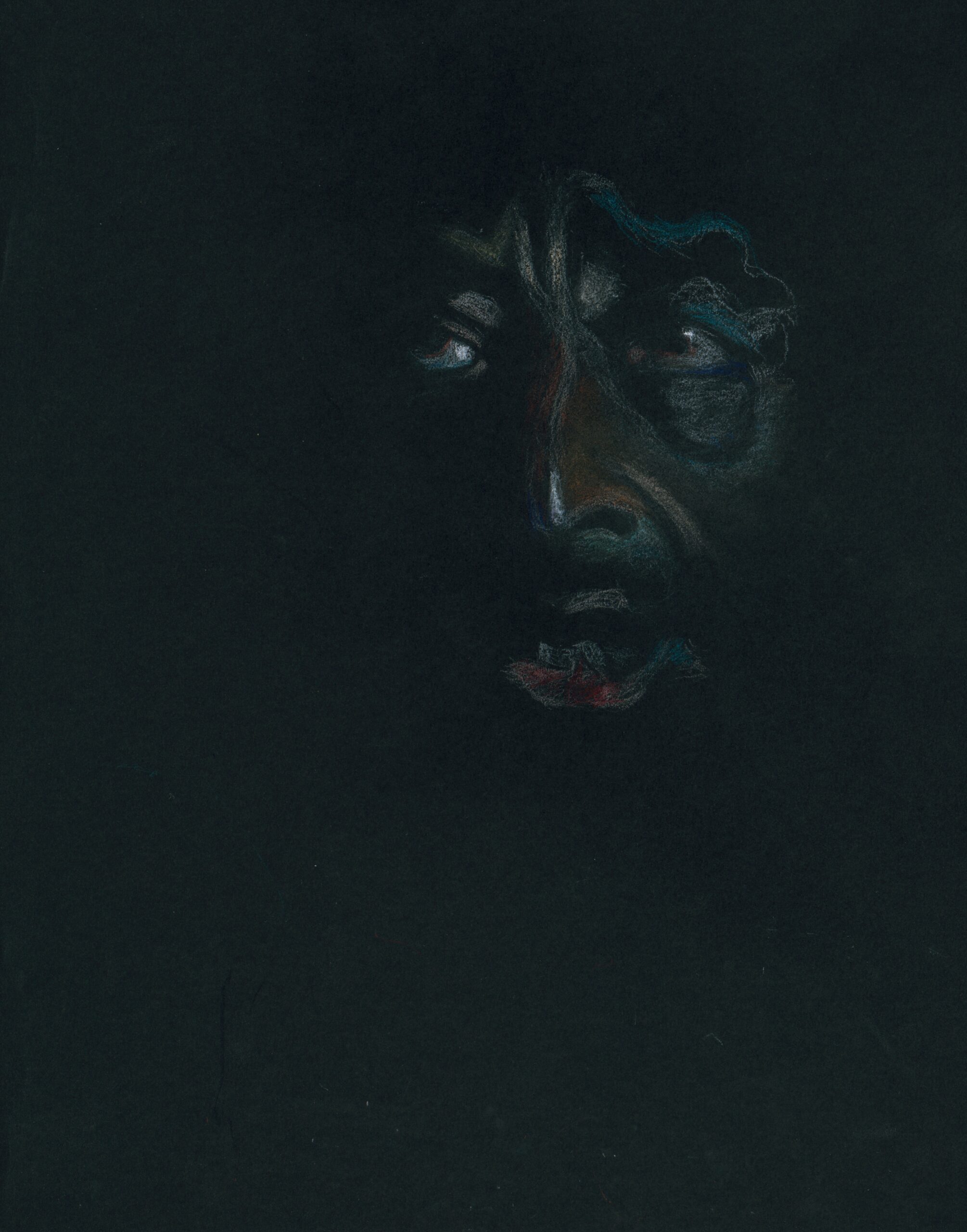

Otherwise, she contains her interpretive and expressive skills in the depiction of the musician himself. In the No. 9 portrait of Yusuf Lateef, the musician who first inspired her to do this series, his eyes glint amid his most prominent features, all hovering in darkness, as striking as the ghost of Hamlet’s father.

Yusef Lateef, by Mary LaRose, pastel on textured art paper, 2021

Pastel crayon is a still-underappreciated medium (which I myself have used extensively). It provides a palpable presence that is perfectly enhanced by the textured black art paper. This embraces the blackness of most of these musicians, but these could be called “noir jazz” portraits, given that noir aesthetics in film, typically accompanied by jazz scores, emerged in the 1940s and ’50s, when most of these musicians got their starts. Time after time, LaRose reveals how shadows haunt and mystify, to varying degrees, each musician, even as her colors render the face vibrant. Most features a distinctly sculpted, though alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons, who played for years with the great pianist Cecil Taylor, is almost abstracted into a dream of a jazz face on Mount Rushmore.

Overall though, there is little mistaking most every musician. So, a fun game to play — for those knowledgeable of jazz reed players from the ’60s and beyond — is to see how many you can identify, without seeing the name on the facing page.

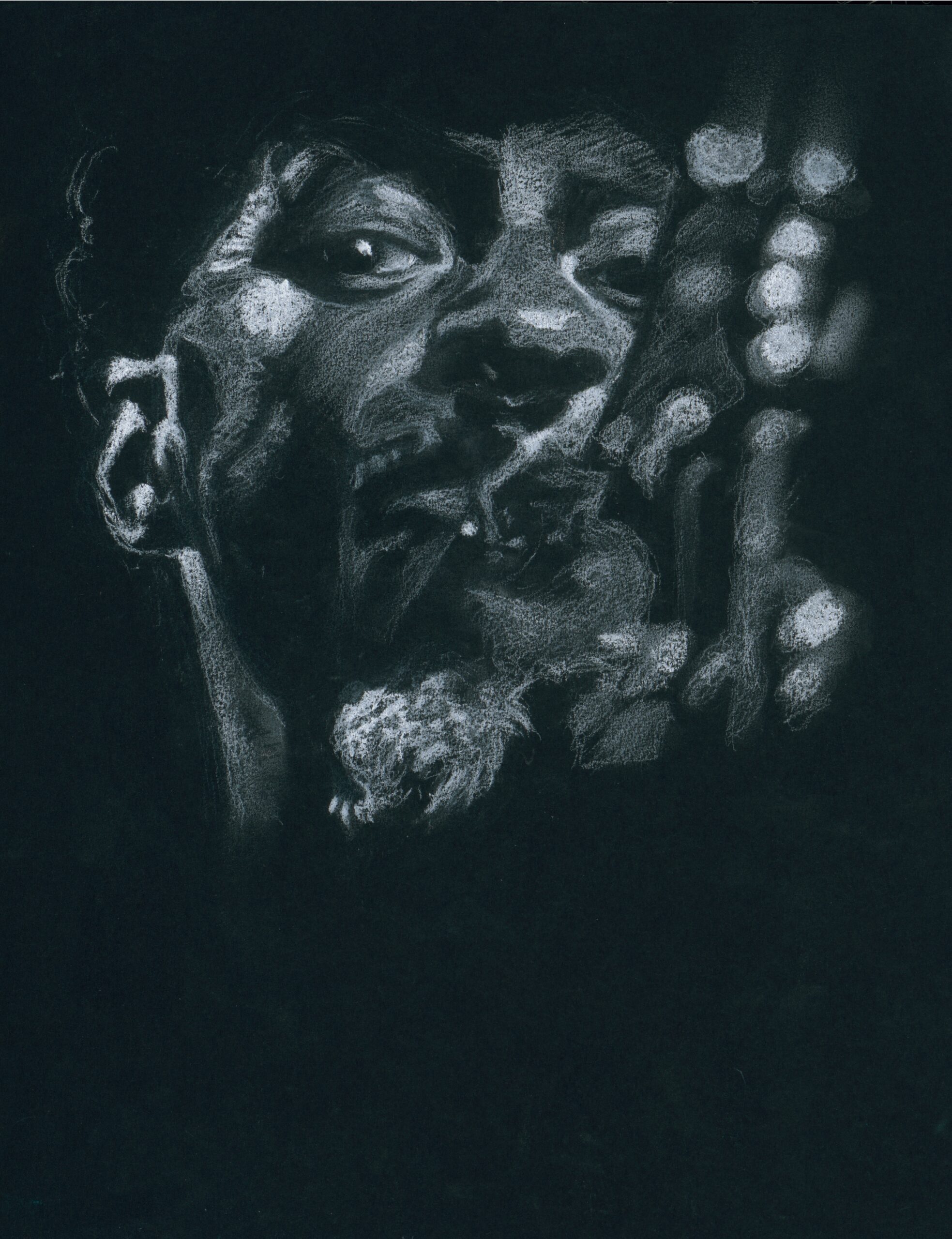

However, the greater value of the book is the expressive artistry LaRose brings to her rough-hewn realism. She superbly she captures the facial traits along with the physical effort and technique necessary to play a reed instrument. In other words – – as her reed-playing husband and musical collaborator Jeff Lederer notes in the book’s introduction – she focuses on the embouchure of each musician, a fair assessment.

Still, it is her hand and eye, guiding the meandering line of pastel crayon on black paper that lends the vitality to these interpretive portraits. That attuned line and mottled texture almost work like a lasso, whirling and catching each subject or, as Miles Davis once put it, “chasing down the voodoo.” This cumulative effect renders them as “black saints,” the title character-type whom Charles Mingus addressed in his masterful album The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady. That titular character was reportedly inspired by Dolphy.

Among her most haunting portraits are two successive ones of the late Albert Ayler, who was found dead in New York’s East River in 1971, a mysterious “drowning” to this day. Ayler possessed a large-eyed countenance of radiant spiritual innocence. In the first portrait, Ayler is not playing. Rather he gazes directly into the viewer’s eyes, possessing here a curious serenity. In the second rendering (below), he’s playing his tenor sax but the eyes still remain riveted on the viewer. Does he see his darkly looming destiny? Or is it a spirit, reflected in you, the recipient of his fire music?

Albert Ayler, by Mary LaRose. Pastel on textured our paper 2021

There are many monochromatic portraits executed in white pastel, and others amount to lively masks of many colors. One of the most striking of those is of Guiseppe Logan who, in a life-worn face of crevasses and cavities, seems to feel “the black man’s burden” Here for every day that his life of abject obscurity subject him to.

Guiseppe Logan, By Mary LaRose, Pastel on textured our paper, 2021

There are six more portraits of Eric Dolphy’s handsome and sensitive face, aside from the cover painting, signifying the importance he holds in LaRose’s eyes. Here we see the range of his virtuosity on flute, alto sax, and bass clarinet. That brings a measure of justice to this musician, especially considering how his career was cut short – by what may have been racist stereotyping judgment by attending doctors when he died, just as this refined man was reaching full maturity as an artist. Not all these men are dead. Yet, such superb portrayals of such blacks saints who were, to varying degrees, “Invisible Men” in their lifetimes, amount to a tender, precious honor to them. With the music, it’s almost as if we can freeze-frame them in our mind’s eye – a moving image of musical life in the very breath of creative ferment.

The book also includes an artist’s statement, an introduction by Lederer, and an index of the video sources for each of the portraits.

Along with the innovative album Out Here, the book Out There is a treasure trove I will revisit often, and learn from, as a visual artist working in the same medium. Yet Out There has traveled far further than any mere academic exercise.

Both the album Out Here and the portrait book Out There are available at the record label’s Bandcamp page, here: https://littleimusic.bandcamp.com/merch

__________

1 Apparently unbeknownst to doctors, Dolphy was a teetotaler who didn’t smoke cigarettes or take drugs.[11]

Ted Curson, a trumpeter who worked with Dolphy in Mingus’s band, remembered: “That really broke me up. When Eric got sick on that date [in Berlin], and him being black and a jazz musician, they thought he was a junkie. Eric didn’t use any drugs. He was a diabetic—all they had to do was take a blood test and they would have found that out. So he died for nothing. They gave him some detox stuff and he died, and nobody ever went into that club in Berlin again. That was the end of that club”.[62] Shortly after Dolphy’s death, Curson recorded and released Tears for Dolphy, featuring a title track that served as an elegy for his friend.

2. LaRose previously did an excellent album titled Reincarnation, taking the same approach to compositions of Charles Mingus, the great bassist, composer and bandleader, who was Dolphy’s longest employer before he went solo.

3. The only recent jazz portrait artist I can think of with comparable quality is Madison-based Martel Chapman, who works in a very different, cubistic style of portraiture.