McCoy Tyner (1938-2020) Photo by Marc Norberg DownBeat

McCoy Tyner’s Quartet performs an extended piece first documented on the live recording “Enlightenment,” with Tyner on piano, Azar Lawrence on saxophone, Juney Booth on bass and Alphonse Mouzon on drums. Courtesy the Jazz Video Guy.

Autumn comes sooner every year, and old man winter howls right ’round the corner. But no, I’m talking now more about the chill down my back and the shudder of a kind of love lost. I’m talking about feeling distraught because I’ve lost more than just a kind of friend. We also lost a god. As well as I knew this artist, I could never touch him, even if I once shook his hand. I’m talking about the titantic pianist McCoy Tyner, who passed away Friday, March 6 at the age of 81.

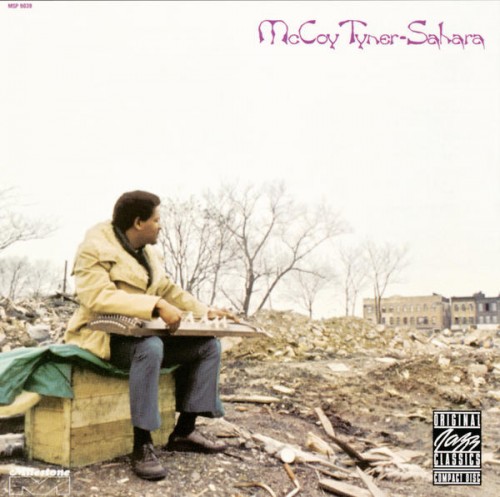

On the other hand, I recall vividly being a Chicago nightclub, where he kindly autographed an album of mine, Sahara, one of the very few times in my journalistic career when I succumbed to the need for some idolizing. I also recall him letting the Milwaukee guitarist Jack Grassel sit in with his band at another Chicago club, from his generous sense that earnest Jack could really play, which he really could, even if McCoy had never heard him.

I call him a friend not because it was mutual, only because I knew him like the back of my hand.

I call him a god because I dearly recall him playing the piano with his uncanny authority and beauty. I always return to one night, when I first heard McCoy break through nocturne into thundering infinity.

I was in college, still living at home, and cocooned in my third-floor bedroom, listening to “The Dark Side,” the all-night radio program of legendary Milwaukee jazz disk jockey Ron Cuzner. Laying on my bed, I felt something in my chest and heart, a swelling that felt the closest I knew to levitation. My small table radio seemed magnified as well. The music was Tyner’s “Ebony Queen,” from his extraordinary new 1972 album Sahara. A stirring, declamatory rhythmic melody rang forth from his piano, and explosive chords erupted from the depths, as his right hand showered sinuous lines of cascading energy, urgency and passion. Soprano saxophonist Sonny Fortune echoed it and added his own bracing solo.

I had never heard anything like this from a piano, such vaulting power and sternly gorgeous soaring, the stuff of eagles on the high seas of atmosphere. Drummer Alphonze Mouzon drove a highly athletic style that fit perfectly, as did bassist Calvin Hill.

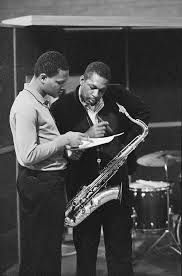

McCoy Tyner and John Coltrane Facebook.com

And I was all the more astonished because I knew Tyner well, from his years with the classic John Coltrane Quartet. He’d been brilliant before, but not dueling with titans on their own turf. Of course, Coltrane was a titan but you always knew he was The One. Now his intensely humble pianist was, as well. He had also been an innovator in his adoption of the eastern modal style but also built on his use of the interval of fourth, all of which set him apart, and had pianists copping him like mad.

“A Prayer for My Family” revealed his long affinity for majestic lyricism. And “Valley of Life” showed him an Eastern searcher, by playing the koto, a Japanese folk string instrument, along with Fortune’s lovely flute.

Sahara‘s centerpiece is the 23-minute title tune — more expansive, eloquent and dynamically ranging, with more head-spinning piano pyrotechnics, a monstrously thunderous left hand, a broad impression of the vast African desert, a world unto itself. Not only had Tyner clearly wood-shedded like a fiend, he now seem endowed with near superhuman powers, extending to his compositions.

When I bought Sahara, my respect for Tyner increased further, because of the understated beauty of the cover. He sat on a wooden box in the middle of a junkyard with an overcast cityscape, holding the Japanese koto in his lap.

Critical praise followed, a Grammy nomination and five stars from Down Beat magazine. There, Michael Bourne raved, “An awesome and visionary artist…’Sahara’ is brilliant… (and Tyner is) one of the most-deserving-to-be-experienced creators in America.”

Yes he’d changed the cultural landscape, and many triumphs would follow, the similar glories of Sama Layuca, and Song for My Lady, the jazz orchestra album Song for the New World, and the muscular exhilaration of the double album Enlightenment, which captured a live quartet concert with imposing power.

He even managed commercial success with the title tune of an album with sap-free string arrangements, Fly with the Wind. Big band and Latin albums would follow and impressive small-combo albums, like the 2-CD all-star Supertrios, and a variety of bands with many artists where he often demonstrated his ability to swing like a mother.

Tyner’s “with-strings” album “Fly With the Wind,” a commercial success. Courtesy dusty groove.

I saw Tyner variously, the early Chicago nightclub dates, and at The Milwaukee Jazz Gallery, where I was so impressed I penned these words in my introduction to the anthology of press coverage for that important Midwestern jazz venue:

“It felt like an intelligent life-force carrying meaningful form, beauty, drama, wit, and mystery. At times the effect challenged my mind and emotions; other times the music exhilarated me.”

I also added that, in a June 1981 interview before his first Milwaukee club date since the 1960s, he told me, “It’s a good feeling to know you contributed something to the world. I’ve had guys back from Vietnam come up to me and say, ‘you helped me through the war.’ Others say,’ you helped me make it through college.’ ” That had to do with the musical and spiritual power of McCoy’s music, and of many who played at the Gallery.

I’ll also cherish a quintet concert in Madison, and a memorable Tyner big band concert at the Chicago Jazz Festival. Here I had a chance to photograph him, and captured visually some of his passion and quiet geniality, (see accompanying photos)

McCoy Tyner at the 2003 Chicago Jazz Festival, leading and conducting his big band which included, in the bottom photo, lead tenor saxophonist Billy Harper, (far left). All fest photos by Kevin Lynch

It was a great period for modern, straight-head jazz, even though the art form struggled during the disco era and always with the commercial dominance of rock. But it retains its artistic power and cultural authenticity with artists like Tyner, and deeply influenced many musical forms, including rock, and became more than ever an international world music.

Yet we also witnessed Tyner’s inevitable physical decline, which revealed his humanity all the more.

So this news was hardly a shock, though powerfully saddening. Of course, we’ll always have the music. What a blessing and inspiration.

It’s also a splendid feeling, how much easier it is to imagine McCoy Tyner flying with the wind.

_________