Courtesy Shifting Paradigm Records

Album review: Johannes Wallmann Precarious Towers (Shifting Paradigm Records)

Pianist-composer-bandleader Johannes Wallmann rises to precipitous heights in his 10th album, Precarious Towers, proving his ability to create a concept album, with the extra-musical aspects streaming gracefully throughout. 1 His band includes Down Beat magazine “rising star,” Chicago alto saxophonist Sharel Cassity, Milwaukee vibraphonist Mitch Shiner, Madison bassist John Christensen, and Milwaukee drummer Devin Drobka. “This is the all-star band from this incredibly fertile region of creative jazz in southern Wisconsin and Chicago that I’ve wanted to put together for years,” Wallmann says.

The album lives up to such expectations. Created during the pandemic, it addresses that experience variously, from the whimsically personal to the overtly political. But the music remains powerfully compelling and listenable modern jazz from one of the Midwest’s supreme musicians, who also leads the jazz studies program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The concept arose from watching his house-bound daughter ambitiously build tall structures with Lego segments, until they fell. Her father sees such effort as reflecting human aspiration, but also hubris. The title tune is indeed rhythmically precarious, with complex off-center tempi, especially from drummer Devin Drobka, a master of striking indirection and accent, while invariably still propelling a tune. Vibist Shiner elicits bluesy feeling reminiscent of Milt Jackson (here, and on the one cover, “Angel Eyes”) and altoist Cassity throughout displays a boppish sax voice that sings as deftly as it swings, a sort of Bird on flaming wings.

“McCoy” honors Wallmann’s greatest pianistic influence in a handsome Tyner-ish minor mode theme. Wallmann unleashes glittering arpeggios and resounding octaves. “Never Pet a Burning Dog” displays the composer’s wit, as an analog to proper pandemic precautions, and the changes here suggest that McCoy Tyner’s modal style is not mutually exclusive from shapely chord changes.

Keyboardist Johannes Wallmann (center) and saxophonist Sharel Cassity, who released the new album “Precarious Towers,” perform together recently at the Madison Jazz Festival. Photo by Kevin Lynch

The album climaxes with a three-part suite titled “Pandemica.” Part one, self-described as “pensive,” unfolds like an adagio etude. Part two, subtitled “Unreliable Narrator,” alludes to today’s head-swimming online media overload, with Shiner’s vibes well-articulating droll commentary. The final movement is explicit: “Defeat and Imprison the Conman Strongman.” It’s a dolorous yet ingenious Dorian-mode theme, with the “cognitive dissonance” of competing lines between bassist John Christensen and Wallmann’s left hand.

The album’s two-part denouement, in effect, is by turns lyrical “Try to Remember” (Wallmann’s tune, not the stage standard), and a fun piece inspired by a Madison tradition, entitled “Saturday Night Meat Raffle,” (to win high-protein food) which conveys a certain off-kilter social dynamic in a Frank Zappa-esque way. Throughout this brilliant album, the band brims with virtuosic elan and restraint, in service of Wallmann’s musical evocation and storytelling.

And Cassity, who recently shone brilliantly (with Wallmann) at the Madison Jazz Festival, is a star in a galaxy that still seems a tad remote from wider appreciation. So, look upward, and listen for her.

One might also read in all this album’s permutations, the precariousness of this nation’s democracy, but infused with hope and collective determination. 2

________

This review was originally published in shorter form in The Shepherd Express, here: https://shepherdexpress.com/music/album-reviews/precarious-towers-by-johannes-wallmann/

- Wallmann’s album last year, Elegy for an Undiscovered Species, for jazz quintet and string orchestra, was named a “best of 2021” album by Down Beat magazine. It was also among the top 10 jazz best albums of 2021 in this writer’s international critics poll. Wallmann also leads the jazz program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, as the inaugural John and Carolyn Peterson Prof. of Jazz Studies.

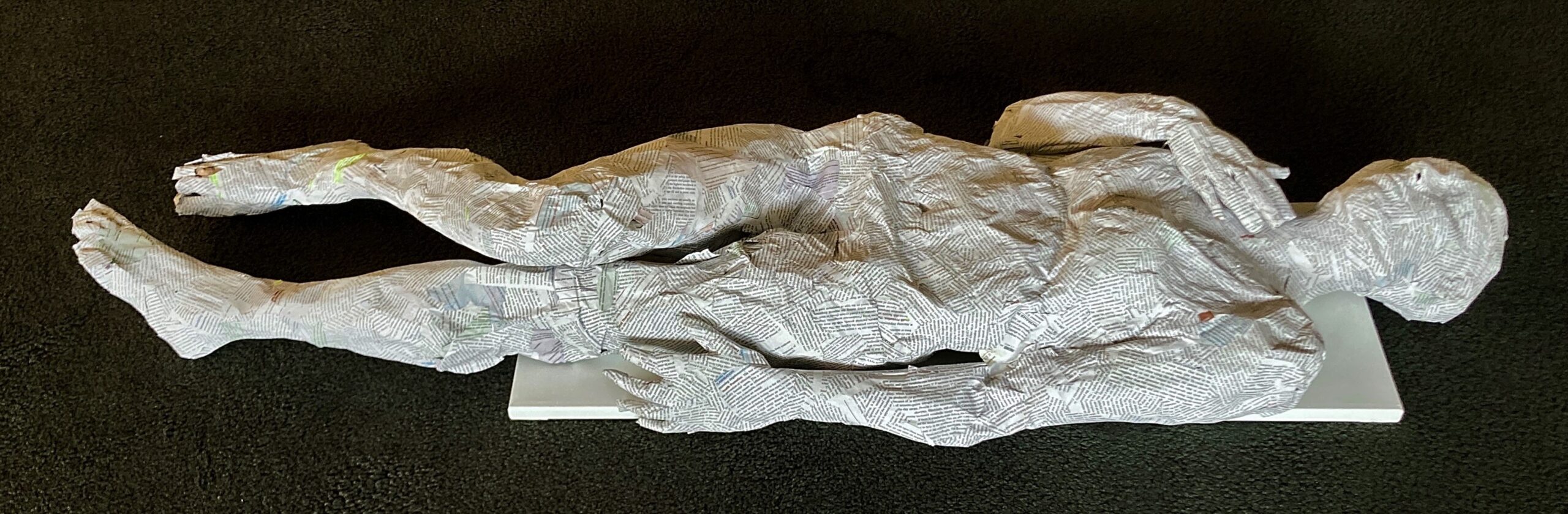

- Another bonus of this album is its delightfully comical (“Look out below!”) cover, courtesy of the uncannily resourceful graphic designer Jamie Breiwick (best known as a jazz musician), employing artwork by Amy Casey. In my book, it’s a candidate for album cover of the year.