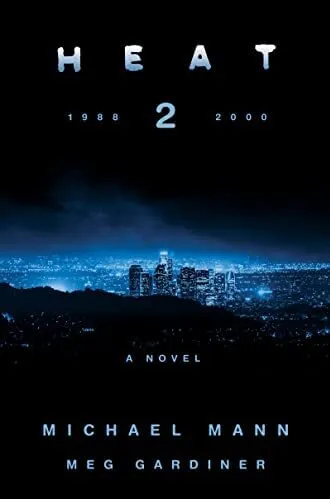

The 2022 novel “Heat 2,” adapted from the 1995 film “Heat,” reached No. 1 on The New York Times best-seller list, encouraging writer-director Michael Mann to begin a new movie version of the novel.

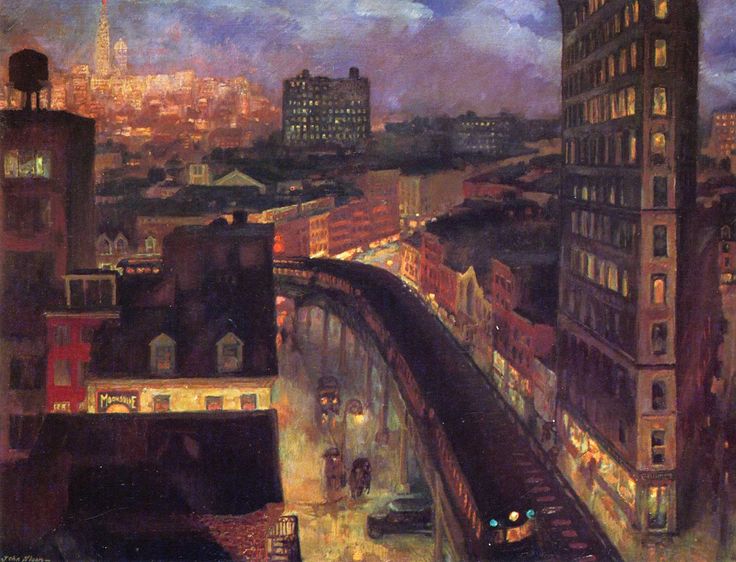

The 1995 film Heat always simmered and glowed, a dangerous film-noir masterwork that cast a long net over contemporary Los Angeles, the megapolis of diamonds, set in an ocean of blackness. It also caught fire and exploded midway, in a dazzling street shoot-out between contemporary cops and robbers. But mostly it felt like a brooding character study of an ostensible “antagonist,” a career criminal, more as the protagonist, with the hyper cop on his trail more as antagonist.

Director screenwriter Michael Mann also plied a plot trope, the now prison-averse bank-hit virtuoso Neil McCauley compelled for one last big score so he can retire securely, out of country. Mann first made a name as executive producer of the hugely influential TV series “Miami Vice” (and later a short-lived cop series, the superior “Crime Story”).

The Chicago native and UW-Madison English lit major who had his life changed by a movie rather than a book when he saw Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 satirical masterwork Dr. Strangelove.

In an LA Weekly interview, he described the film’s impact on him:

It said to my whole generation of filmmakers that you could make an individual statement of high integrity and have that film be successfully seen by a mass audience all at the same time. In other words, you didn’t have to be making Seven Brides for Seven Brothers if you wanted to work in the mainstream film industry, or be reduced to niche filmmaking if you wanted to be serious about cinema. So that’s what Kubrick meant, aside from the fact that Strangelove was a revelation.[10]

Mann graduated from Wisconsin with a B.A. in 1965. He earned an M.A. at the London School of Film in 1967.

Starkly Beautiful, High Tech

Kubrick’s austere high-tech visual spaciousness is evident in Mann’s style, and over the years Mann has revealed a predilection for somewhat unconventional heroes, or antiheroes, back in his first successful film 1981’s Thief, an immersive portrait of a criminal played by the always-interesting James Caan. Mann used actual former professional burglars to keep the technical scenes as genuine as possible. In 1986 he did Manhunter, the noirish police procedural that introduced genius-criminal Hannibal Lector (played by Brian Cox) to the movie world (and opened the door to Anthony Hopkins much broader version of Lector in Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs). And in 2004, Mann cast good guy-hero Tom Cruise against type as a hit man in Collateral. (I haven’t seen his new film Ferrari, but the titular real-life race-car driver and designer seems to fit the pattern.)

Insightful film critic/historian David Thomson writes: “No one has done more to uphold, extend and enrich the film noir genre than Michael Mann.”

Mann has also delivered brilliant portraits of tobacco industry whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand in The Insider and of arguably the most famous, extroverted and unconventional athlete, of his era in Ali.

By contrast, McCauley wants to be as invisible as possible. Much of his success as a high-end bank robber has to do with his mental discipline and strategies, developed as a Marine. He’s capable of killing, but only of necessity.

In a pivotal scene, unbeknownst to Robert De Niro’s McCauley, Al Pacino’s LAPD Detective Vincent Hanna and officers wait inside a shipping container watching the events from a live infrared surveillance feed. Then, a police officer decides to sit down in the corner, his equipment making a thump as it meets the container’s edge. McCauley stares at the container, knowing something isn’t right, and aborts the lucrative job.

It’s parallel to a similar situation in which the real-life Neil McCauley aborted a job which led to the real-life cop after him (Chicago PD detective Chuck Adamson, a consultant to Heat) to grow to admire him for his professionalism.

Cat and Mouse

Amid a lot of brain-bending cat-and-mouse, Hanna thinks he’s getting to know McCauley and chases him down in a car, without probable cause at that point, only to walk up and invite him for coffee.

Ever-cool, McCauley agrees (coffee is a small weakness of his), and the ensuing scene between two indelible actors includes both sharing symbolic recurring dreams, each revealing vulnerabilities. Then McCauley steels himself again, lays out his tough-minded situational philosophy, delivered with DeNiro’s clipped yet soft-spoken rectitude: “I guy told me one time, ‘Don’t let yourself get attached to anything you’re not willing walk out on in 30 seconds flat, if you feel the heat around the corner.’”

Verbally jousting again, both men make it clear they will not hesitate to kill the other, if they encounter each other in a do-or-die situation (Hanna’s motive more ostensibly high-minded).

The iconic coffee house scene from Michael Mann’s “Heat” was based on an actual meeting between the real-life Neil McCauley and Chicago police officer Chuck Adamson. Courtesy Warner Brothers

A coffee chat between the real-life McCauley and Adamson, “the heat,” inspired Mann’s interest in the historical story, and the movie idea. In 1962, McCauley had already spent 25 years behind bars — more than half his life. He had spent eight years in Alcatraz, with four years in solitary confinement.

The film version of McCauley’s self-discipline is tested when he falls into a personal relationship he hopes to cultivate once he’s retired. He meets the young woman named Eady, played poignantly by Amy Brenneman, in a coffee shop, where the lonely woman unsuspectingly makes the first move on the dark, sharply-dressed stranger. He will keep his real work secret from her.

Though Eady (Amy Brenneman), makes the first move, career criminal Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro) offers a hand in friendship after the ice is broken. theatretimes,org

The film plot builds to McCauley’s crew attempting a $12 million bank robbery. The final climactic one-on-one chase scene between the two star actors is austerely beautiful in its suspense, its editing, noir cinematography and music, almost balletic in its physical dynamics.

I revisit the film, to refresh memories, or to urge those who haven’t to discover it, “one of the best-made films of the decade” which rewards repeated viewing, Thomson asserts. It’s also to note the unusual novel Heat 2, written by Mann years after his film, which clearly haunted him, and co-written by accomplished thriller author Meg Gardiner. Nor did the “sequel” come ASAP after the original to capitalize on the first film’s success. And Mann reversed the typical pattern of book-to-film. This is clearly a mature artist, allowing a story concept, a saga, to gestate over years and indeed the novel story line is more ambitious than Heat.

Best Seller List

Published last August, Heat 2 rose to the top of The New York Times best seller list, reflecting the film’s power and prestige, and the book’s superbly vivid yet hard-boiled narrative. Mann is in negotiation with Warner Brothers for the film version, with Adam Driver potentially set to play the younger McCauley circa 1988, Ana de Armas as his love interest, and Austin Butler in the expanded role as McCauley’s right-hand man Chris Shiherlis who, unlike his boss, barely survives the original Heat.

Reading the book, I wondered whether Mann would attempt to film it. This story arc ranges from 1988, a decade before the events in Heat — Hanna is cutting his teeth as a rising star in the Chicago police department chasing an ultraviolent gang of home invaders.

The sequel section, in 2000, sprawls a bit with a sub-plot on the Mexican/U.S. border and into Paraguay in Chris’s growing involvement with high-end weapons technology bidding between two Asian crime families.

How well might this work as a movie? Mann has proven adept at longer storylines, as in Ali, The Insider, The Last of the Mohicans and Manhunter. The characters dimensions lay in the weeds, as he’d already sketched them out deeply for the Heat actors to absorb in the original screenplay. But when I got to this book’s climax, I sensed its magnetic pull on the director: to become perhaps his most ambitious stab at virtuoso action-film scene orchestration.

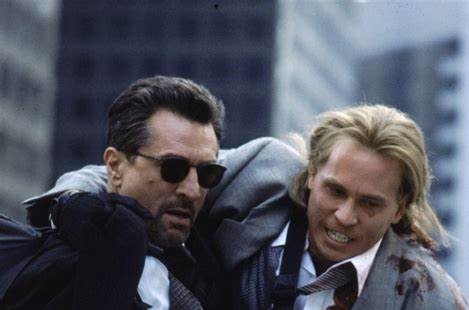

The extended scene is brilliantly written in the book, so I’m optimistic. Which brings me to the question of how two people write a novel together. I would imagine that Gardiner wrote most of the actual narration and dialog, while Mann probably developed the storyline, attempting to flesh out his main characters’ prequels and sequels to Heat. Besides learning plenty about fictionalized pre-Heat McCauley, who clearly is the central figure, we get plenty more about Chris Shiherlis (played vividly by Val Kilmer in Heat), who considered McCauley his “brother from another mother.” Though now involved, partly by professional necessity, with a female Asian crime family boss, Chris still carries a torch for his ex-wife Charlene (played by Ashley Judd in the film).

Neil McCauley Robert De Niro) helps his injured partner Chris Shiherlis (Val Kilmer) to safety in the big shootout scene in “Heat.” 1movies.life

Complex, Clean Aesthetics

Chris doubtless admired McCauley’s moral code, loyalty to his men who don’t screw up, and a theft style of complex yet almost clean aesthetics, which arises when he addresses the people trapped in the bank: “We want to hurt no one. We are here for the bank’s money, not your money. Your money is insured by the federal government. Think of your families. Don’t risk your life. Don’t try and be a hero.”

Here we see what the younger McCauley may have learned the hard way. In the prequel section of the novel Heat 2, McCauley himself is compelled to try to be the hero, to save his girlfriend Elisa — in the grip of the serial house burglar-killer-rapist Otis Wardell, and three others of his crew. McCauley has the comparative advantage of surprise but is outnumbered. Wardell survives McCauley’s sniper-pick-off of his three men.

In the sequel section, when Wardell catches up with Elisa’s daughter Gabriela, the only witness to her mother’s murder, Detective Hannah is now hot on Wardell’s trail, but a few steps behind directly protecting the young woman. Meanwhile, someone is also murderously closing in on Hannah…This leads to the rather breathtaking – even to read and imagine it – climactic scene.

I am really looking forward to Mann and his ace film team’s open-field running through the scene’s swarming, chaotic danger.

In his career-long inquiry into the noir genre’s implications, Mann seems to be creeping towards capture – of pure tragedy as identified by Camus, in which both purveyors of good and evil appear justified to cross the line into the other’s moral realm. Then, only a Greek chorus-like spiritual imploring to eternal mysteries remains to console our bereft souls. Ever-doomed McCauley here seems a full-fledged tragic figure. Hanna’s compulsions, meanwhile, put him at risk of betraying both true righteousness with the self-righteousness of hubris, and “the greater good.”

The novel seems to extend a dominant theme in Mann’s work “the ferocity and absurdity of the attempt to find redemption in hell,” as Thomson darkly puts it. 1

Still, if dedicated, chase-addicted cops like Lt. Hanna (from “The City of Angels”) stay in the hunt, some cops may still be gaining on, and outrunning, the devil.

_______________

This article was previously published in a slightly different form in The Shepherd Express, here: https://shepherdexpress.com/film/reviews/firing-up-the-heat-with-director-michael-mann/

- Wikipedia: Scott Foundas, (July 26, 2006). “A Mann’s Man’s World”. LA Weekly. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- David Thomson quotes from The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, Knopf, 2002, 560-561