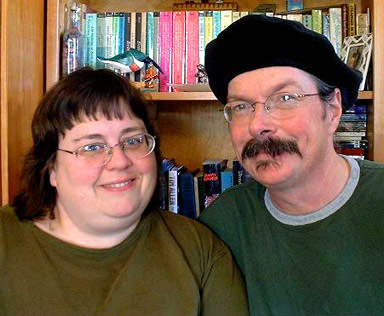

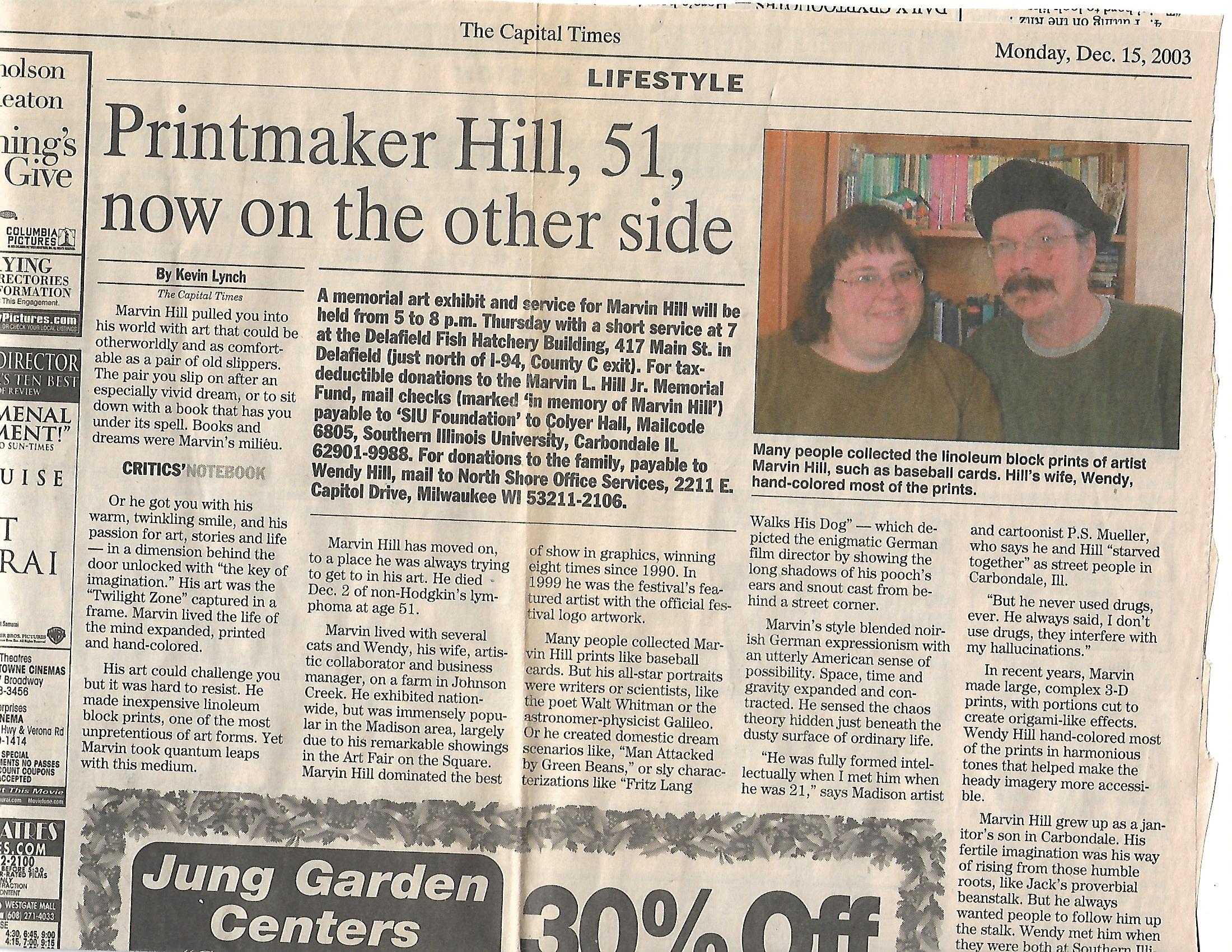

A prize possession of The Milwaukee Art Museum’s “Ashcan School” collection is the large painting “The Sawdust Trail,” from 1916 by George Bellows. Milwaukee Art Museum

Happy New Year Culture Currents readers!

Notice: I’m reposting this review because I chose a favorite John Sloan painting for my new Culture Currents blog theme, the night-time image (at top). This painting “Six-O’Clock, Winter,” (1912) is not in the Milwaukee show but there’s more than enough that’s well worth seeing.

Also, it’s easy to let an art show run slip by: THIS EXHIBIT RUNS THROUGH FERUARY 19. It’s a great tribute to the artwork in the MAM’s permanent collection. Speaking of visual art, The Ashcan School was “the first American art form.”

Art Review:

The Ashcan School and The Eight: Creating a National Art. The Milwaukee Art Museum, through February 19, 2023. Bradley Family Gallery

For information and tickets: https://mam.org/exhibitions/details/ashcan-and-the-eight.php

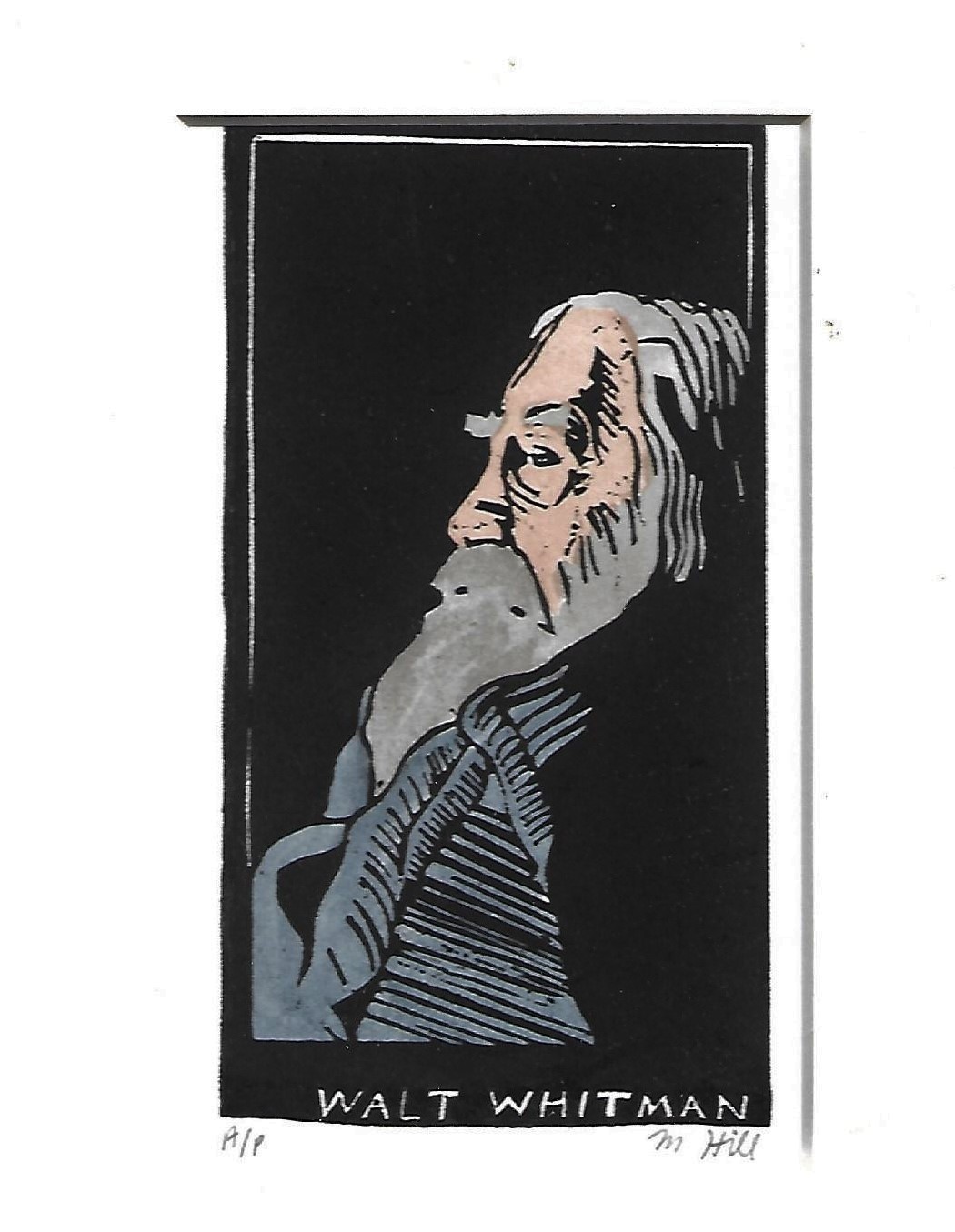

To see a world in a grain of sand” poet William Blake once put it. Later, American poet Walt Whitman would see “a grain of sand” as no less perfect than a leaf of grass.”

These great modernist poets saw things profoundly magnified in the humblest of earthly entities, light years from most of the art and music that for centuries courted royalty. So perhaps it was inevitable that the nation built on the anti-regal and messy moorings of democracy foster an art movement antithetical to royalty-schmoozing. Rather, one of the commonfolk, at least in its ideals. This American motherlode would bear the nation’s first “national art.”

Known as The Ashcan School, its name derived from a pejorative critical comment that the art was as good as “a can of ashes.” But in that comment’s snoot the artists saw soot, as in a poetical paradox. The ashes contained dirt, enough to allow seedlings to grow and tilt toward social justice, found in artistic truth. That is, a great, if profoundly flawed nation’s life and essence might be extrapolated from something as slight as a cigarette butt’s droppings.

The Milwaukee Art Museum’s The Ashcan School and The Eight: Creating a National Art allows Americans to see themselves in the early 20th century, a time of great cultural upheaval, a nation shapeshifting in its peculiar genius — troubled, compulsively creative, proud, and quotidian. It was also struggling through the first World War with the Great Depression around the corner. Yet immigrants poured in, adding diversity, labor energy, and societal tension. Perhaps more than anything, modernism’s post-industrial revolution had shackled and driven America.

How did the Ashcan School capture all this? First, they objected to exhibition practices that they considered restrictive and conservative. They often employed an expressionistic, painterly style to portray gritty and downtrodden subjects previously deemed inappropriate for high art and museums, the stuff of “ashcans.”

Accordingly, the museum’s curators and guest show catalog essayists draw parallels to cultural and social issues still relevant today.

The Art Museum owns one of the nation’s largest collections of works by the Ashcan School, and this is the first exhibit to include nearly the entire 150-object collection, says curator Brandon Ruud. Prints, drawings, paintings, and pastels represent artists of the so-called “The Eight,” who largely produced the Ashcan style and sensibility: Robert Henri, John Sloan, George Luks, George Bellows, Everett Shinn, William Glackens, Arthur Bowen Davies, Maurice Prendergast. Several affiliated artists like Stuart Davis reveal the full range of the group’s subjects and artistic practices.

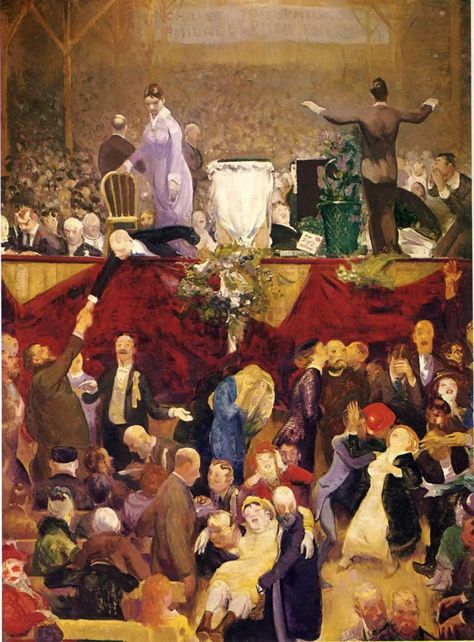

One’s eye might easily gravitate to a large painting in the show, Bellows’ “The Sawdust Trail,” by traditional measures of scale and complexity a “masterpiece,” even though the group’s aesthetics strove to burrow beneath grand art conventions that may obscure the truth as they saw it. The painting earns its renown, an epic canvas with a cinematic view of a religious revival meeting.

It tells a rich and sardonic story of post-Puritan American impulses that continue to this day in evangelic churches. The charismatic preacher, named for a real historical figure, Billy Sunday, would solicit salvation while typically delivering a thunder-and-lightning sermon to spook believers out of their savings. The air above his big tent virtually billows with a dense cloud of sun-lit smoke that might easily exalt the illusion of the divine.

Billy Sunday himself glad-hands one convert. Is he still a man of the people or is this just the old quotidian poseur, compulsively pressing flesh, greasing it to open the wallet? Meanwhile, several women faint (from the fumes of divine inspiration?) amid the dense, motley crowd. Exaltation, or delusion, or some other strange strain of behavior is distinctly American as it is universal, to see the “MAGA” power deluding today, and the global trend to political authoritarianism.

A man with that kind of power might be a Republican presidential candidate — if he can beat out Donald Trump who, heathen though he may be, knows most of the preacher’s hidden gifts for dark persuasion and personality-cult politics.

An even more insidious example of how compromised holiness undermines the truth is Mike Pence, who has said he will not testify to Congress about the January 6 insurrection, even though he was a primary execution target. He’s played it politically all the way, claiming a dubious “separation of powers” privilege — only because he survived.

So, these Ashcan diggers uncovered America haunted by cycles of power as old and foreshadowing as the first conquests of Native Americans and slavery.

Yet one might better experience this exhibit on a smaller scale, as a kind of forensic mystery, investigating the human figures that tell personal stories of lives possibly forsaken or transgressed.

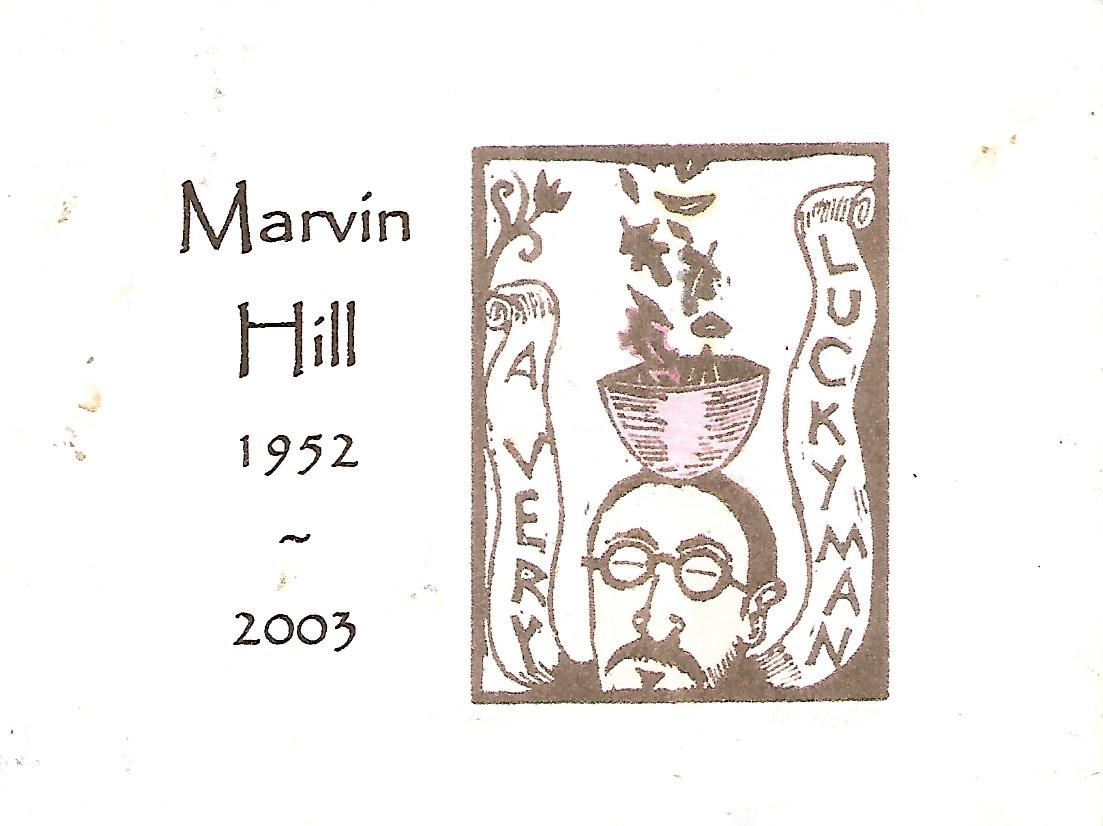

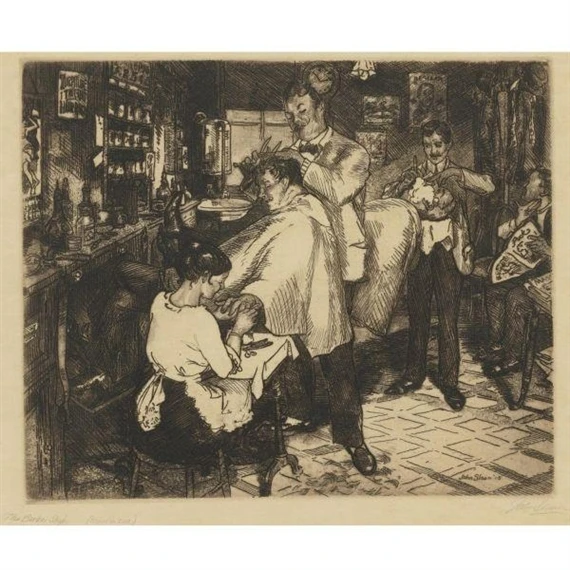

John Sloan The Barbershop, etching and aquatint, 1915, MutualArt.com

Zoom down from, say, the atmospheric expanse of “The Sawdust Trail” to individual figures in intimately revealing scenes. No one surpassed painter-printmaker John Sloan at carving out these small-window revelations of what would become known as Americana, in a land still grappling with its identity.

The class-laden print The Barbershop animates to the point of satirical comedy. A crowded barbershop is recast as a tableau of sublimated class-warfare. The two men being serviced clearly reign. One seems to eye, with lust or disdain, a young lower-class woman manicuring him. Seated in waiting, a middle-class man reads the satirical Puck magazine, and beside him lies a subversive Marxist magazine called The Masses, for which Sloan served as art editor. The complex, beautiful composition (less than 10 by 12 inches) is riddled with America’s contradictions of social indulgence and defiance.

Among Sloan’s numerously displayed gritty parables of the underclass is Night Windows. A Peeping Tom husband spies on a bathing neighbor in a nearby window, while his wife hangs out his family’s laundry amid squalling children. In Sloan’s world, God may or may not have been invited for dinner. They are too busy trying to put bread on the table for the brood.

Robert Henri, Dutch Joe, (or Jopi van Slooten), oil (24 by 20 inches), 1910, Pinterest

Robert Henri, who was the movement’s leader, had the portraiture skill to humanize the mother, the man, or boy, in the brood.

Witness his marvelous portrait of a street urchin named Dutch Joe, (or Jopi van Slooten), from 1910. In this bundle of mischief, you sense potential, yet risk. “The disparity between the innocence of the hero and the destructive character of his experience defines his concrete, or existential, situation.” That’s how American literary critic Ihab Hassan characterized what he called America’s “radical innocence.” 2 It entailed the possibility that, in his scruffy vigor, brash will and ingenuity, Joe might get ahead in the world, or be swallowed up in it.

This show is populated with a fascinating array of colorful actors, many of problematic agency.

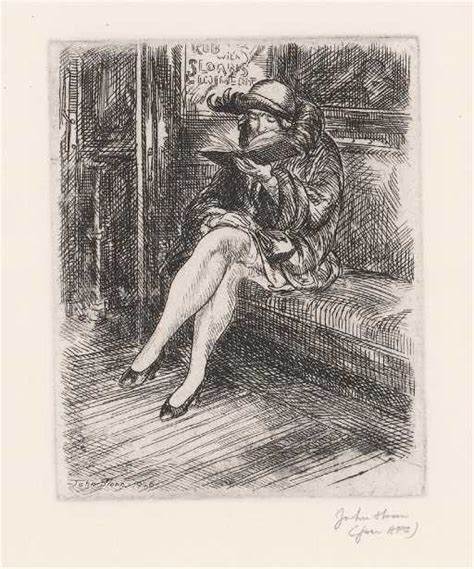

John Sloan, Reading in a Subway, etching, 1926. Pinterest

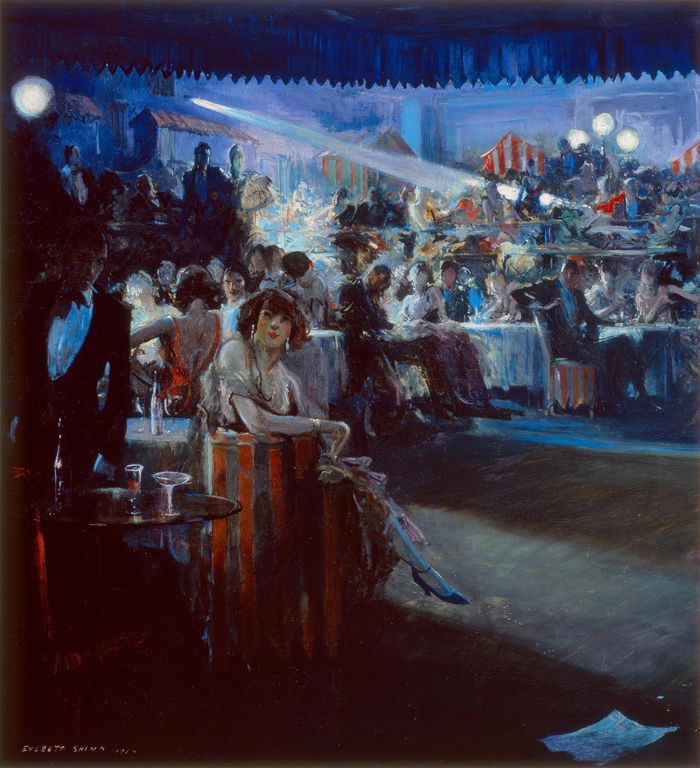

Everett Shinn, The Nightclub Scene, oil, (36 by 34 inches) 1934

From Shinn’s iridescent Nightclub Scene to Sloan’s bundled-from-the-cold flapper in Reading in a Subway, or the vibrant gaggle of 9-to-5 women in Return from the Toil, these artists encounter a diverse populous and gives lie to the contemporary criticism (on an exhibit wall commentary) that these artists diminished women and minorities in the class-struggle tableaux. They were doubtless men of their time, subject to certain biases, but by this evidence they strove for greater understanding and truth of how we live together, and in isolation, in America, to envision a real yet better way, one quotidian day at a time.

In other words, they often told a small “d” democratic story, creating heroes among quietly courageous women and other folks hidden in the cracks of society.

And the men depicted are often satirical subjects of classism and sexism, as in preacher Billy Sunday and Sloan’s “Barbershop” scene.

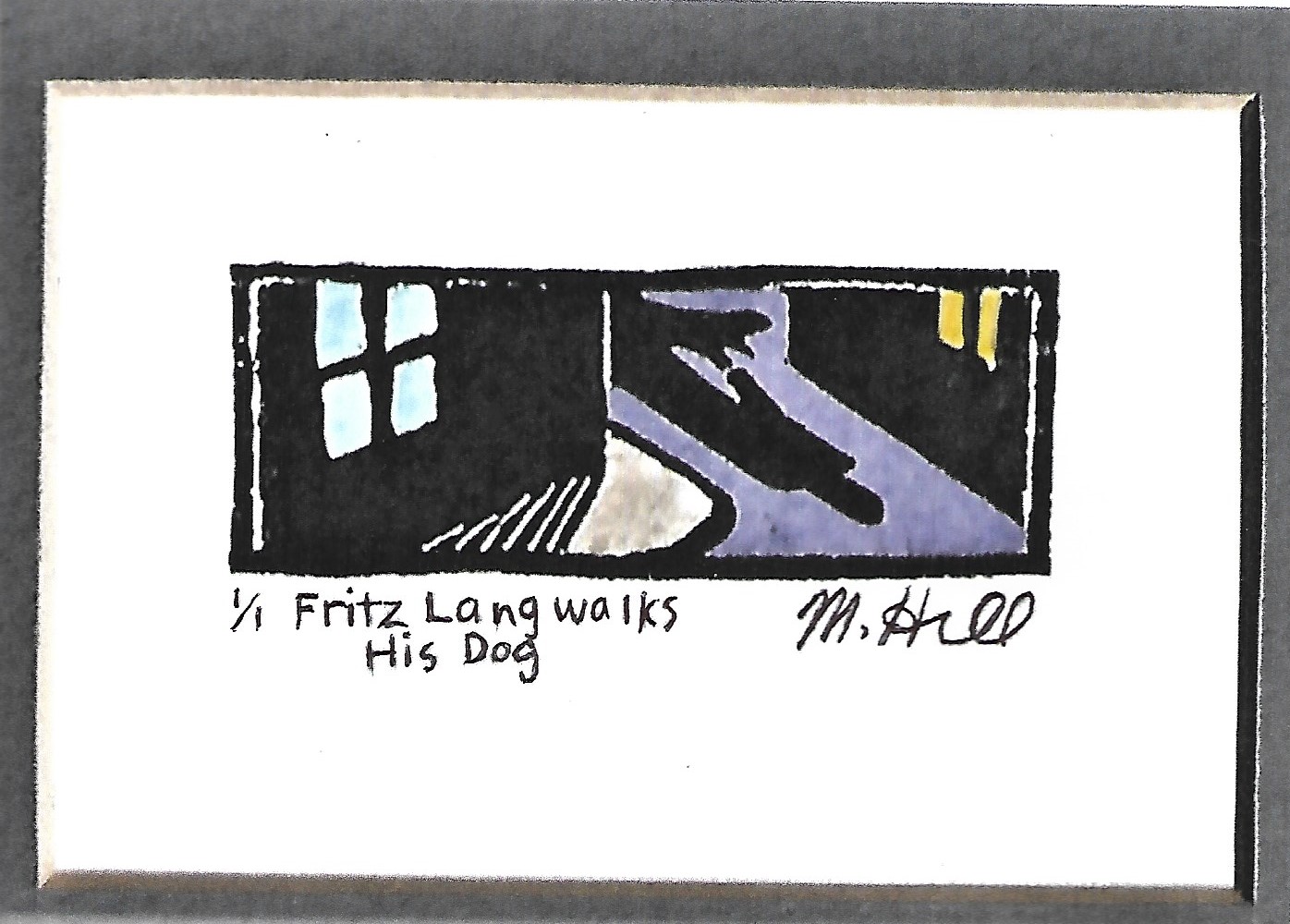

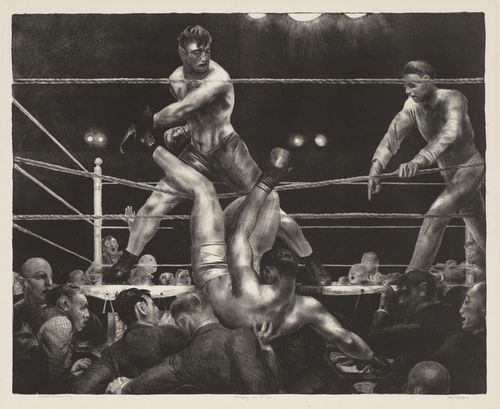

George Bellows, Dempsey and Firpo, lithograph, 1923-24, (18 by 22 1/4 inches), Pinterest

Perhaps the most famous image in the show is Dempsey and Firpo, the lithograph print that led to George Bellows’ explosive painting of a big-time heavyweight boxing match, a literal witnessing of the brutal sport that came of age in this era. “When Dempsey was knocked through the ropes he fell in my lap,” Bellows explained to Henri. “I cursed him a bit and placed him carefully back in the ring.” So, Bellows justifiably includes himself in the painting’s corner, a bit like director Alfred Hitchcock’s impish cameo appearances.

Bellows had studied art under Henri. John Fagg’s superb catalog essay describes how “Henri encouraged his students both to scour city streets for inspiration and to read widely and embrace culture in all its forms.” This sounds like the best kind of voraciousness that would exemplify the American striving these artists documented and interpreted, warts and all.

“Henri talked not only about the students’ paintings but also about music, literature, and life in general, and in a very stimulating manner, and his lectures constituted a liberal education,” recalled Stuart Davis. 3

This exhibit constitutes such an education, as rare as it is valuable, at a time when it feels sorely needed. If you want to learn about confounding America, of both yesterday and today, in the Faulknerian sense that the past is never dead, this Ashcan art provides you, in immersive depth, yet free of academic pretenses, though the catalogue essays are welcome. It is an experience of vast pleasures amid what Duke Ellington called murmuring “Harlem airshafts,” and Hitchcock’s rear windows, and pregnant, grimy shadows of night. 4

___________________

This review was originally published in a slightly shorter form in The Shepherd Express: here: https://shepherdexpress.com/culture/visual-art/america-unvarnished-in-mams-ash-can-school-exhibit/

1 The exhibit also includes a lithograph version of The Sawdust Trail, which shows more of the fine details in the dense composition.

2 Ihab Hassan, Radical Innocence: The Contemporary American Novel, Princeton, 1961, 7

3 John Fagg, “The Unseen City: The Ashcan School’s New York,” The Ashcan School and The Eight: Creating a National Art, show catalog, The Milwaukee Art Museum 2022, 78

4 A reflection of this collection’s ongoing contemporary relevance and vitality is that it is still growing even after decades. A primary curator of the show, Brandon Rudd explained to me: “One of the truly amazing things about the Ashcan School collection is that it is both such an integral part of the Museum’s rich history and is also active and growing: This exhibition features new acquisitions and never-before-seen donations, as well as loans from private collections in the Milwaukee community and works rarely displayed or seen by the public because of their fragility.”