Ron Cuzner (Courtesy facebook.com

It was eleven years ago today, March 27 of 2003, when my mother called me from Milwaukee and told me Ron Cuzner had died that day, at 64. I was stunned to a Cuzner-like pregnant-pause silence. I had moved to Madison in 1989, so I lost my close connection to Ron in those pre-radio streaming years.

He had done his last Ellington “Solitude” intro, and uttered his last golden catch-phrase.

He and his jazz program The Dark Side had finally moved on to the light. 1

Cuzner was the one-of-a-kind disk jockey who exposed countless nocturnal Milwaukeeans to his beloved music on various radio venues, starting in 1968 with an “underground radio” station (along with WUWM’s Bob Reitman). His longest tenure was at the otherwise-classical music WFMR. Cuzner’s preferred time slot was midnight to sunrise. Yet hardly a vampire, he also emceed high-profile jazz concerts and ran a small jazz record store downtown.

Long-time Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel media critic Duane Dudek deemed him probably “the most singular stylist in Milwaukee radio history,” who “took a slow drawl, meticulous diction and an encyclopedic knowledge of jazz to almost every radio station in the city.” 2

In the darkness, he took his sweet time with you. Cuzner’s on-air silences involved exquisite timing between words or phrases — inserting languid grace into his delivery — the opposite of Top 40 DJ hyper-prattle. And sometimes, after the silence, the concluding phrase would be in a slightly lower, softer register: “With a song…in my heart.” He knew how such a deflation of tone could convey emotion, and sometimes pathos.

This guy from Racine would quote a humbling lyric: “They’re playing songs of love, but not for me.” He faithfully carried the torch for jazz but also another flame, for all the lonely people listening to him. Yes, his music kept him company through all those long, dark nights. But back then, he never knew really who or how many people were actually listening.

So Cuzner surely spent countless nights utterly alone until sunrise, feeling sometimes like the most forsaken bluesman. He likely suffered, at times, a bit of Naked City paranoia. He obsessively marked his name on most of his 10,000 CD cases and discs. His vast LP collection is gone, but his wife Janet donated his CDs to the library of the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music.

Cuzner’s program migrated almost as often as a restless pied piper, partly because of his dedication to a quintessentially American music that grew up flirting with commercial instincts like an illicit lover. But also radio station managers would simply pull the plug on his show — either a callow son-in-law program manager changing formats willy-nilly, or simply for tiring of Cuzner. But he understood the mercurial, ratings-obsessed radio business.

So, perhaps his style involved some self-preservation, the cool hipster carrying deep loss on his shoulders with effortless style. That announcing style had what some deemed a faintly patrician insouciance, with impeccable yet fluid and mellow diction. Somebody once niftily characterized his delivery as “an English butler who’d had a few martinis.” ( You can access podcasts of many of his shows on ITunes and on the Ron Cuzner Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Ron-Cuzner/97979281464.

Another priceless bit, audible on the 7-11-99 podcast, is about how his grandmother “used to bake me pies and cookies and things; and she called me Butchie…” That one grew out, no doubt, of one of his signature bits: “I sincerely hope you are warm tonight, and that you are together tonight, and that your cookie jar is filled to the very brim… with the cookies of your choice, of course.”

These sugary bits had very personal resonance and poignancy, because Cuzner was a diabetic, and he died of that condition. Yes, his on-air persona was masterful shtick that grated on some people. But in retrospect, with nothing but recordings of him, the shtick is precious, in the best sense.

In person, he was laid back, soft-spoken, and yet articulate with, I think, a natural ease with diction. Unlike many of us, he took care to say what he meant as precisely and as well as possible, to honor his own thoughts. How many of us bother to do that anymore in conversation, or even when texting? Dwindling attention spans may have to do with human behavior as well as all the technology engulfing over our lives. So Cuzner ended up making a helluva lot of sense when you talked to him. Are there other people out there, who knew Ron or his show, who know what I’m talking about?

Most Cuzner fans likely have some great nocturnal memories of “The Dark Side.” If you were lucky enough not to be alone, how many times did he assist in a seduction, or in rekindled lovemaking? An indelible memory for me was the night — while half asleep in my bedroom darkness — a thundering and clarion music broke unannounced from my radio speaker. The piano style sounded familiar but I’d never heard it ringing and roaring with such hair-raising authority.

When Cuzner announced the title “Ebony Queen” I learned it was from the new album by McCoy Tyner, Sahara. It was the breakout album of Tyner’s career. After leaving Blue Note Records, he had wood-shedded for several years and signed a new contract with Milestone Records. This was his first album since fully mastering an extraordinarily muscular new technique and expressive concept, bolstered by lightning bolt left-hand bombs, and piston-powered right-hand abandon. A deeply sonorous eloquence now informed his intimate lyricism. Tyner had reach an artistic level commensurate to his former bandleader, John Coltrane. It led to the most successful period of Tyner’s career, and demonstrated how bracing, inspired jazz could have commercial power.

And it was Cuzner who turned me onto this pivotal moment in the music’s history, among others.

He also aired his own critical opinion at times. He once commented on a Down Beat magazine review which referred to pianist Mulgrew Miller, bassist George Mraz and trumpeter Lew Soloff as “also-rans.” Then he played a dazzling cut from the recording of the three musicians. At the end, he repeated their names and added, “also-rans, indeed,” his voice dripping with irony. We lived in “Henry’s city,” as he put it, referencing Milwaukee’s long-time and sometimes baronial mayor Henry Maier. But from midnight to dawn, it was Cuzner’s city.

The dark side of Ron Cuzner’s city. Courtesy facebook.com

He was a good friend to me and many members of the jazz community, especially the musicians, who often listened to Cuzner coming home from their late-night gigs. 3 We befriended each other when Ron became a customer of mine at Radio Doctors “Soul Shop” on Third and North Avenue, where I was the jazz record buyer. Later, I covered jazz for The Milwaukee Journal. Ron would eventually get me my first radio job, as a DJ at WLUM, when he left that station. 4

Ron Cuzner conducts an on air pow-wow with Milwaukee jazz musicians. Seated (from left to right) are trombonist Steve Blonien, pianist Ray Tabs, saxophonist Hattush Alexander, bassist Lee Burrows, trumpeter Tom Baker, saxophonist Warren Wiegratz and Cuzner. Courtesy rickjonesjazz.com.

I’m sure Cuzner had many highs and lows in his great career. But because he was there when we went to sleep, or when we couldn’t sleep — there for our highs and lows — he and his music became good friends for many people who never met him. 5

Ron Cuzner was, in his way, our musical consciousness. One of my personal favorite Cuznerisms was, “Twenty-two minutes after the hour. And the hour, of course …is absolutely inconsequential.” That’s funny, but it also conveys some of Cuzner’s hip, open-minded philosophy and the program’s aura of wee-hours timelessness. For years, many of us fell asleep to Cuzner, so he likely entered the corridors of our dreams, with his jazz infiltrating our alpha waves.

A Keith Jarrett album title sums up Cuzner well: The Melody At Night, With You.

Finally here’s Ron’s own farewell, a recording of his closing to his program each sunrise, accompanied by pianist Don Shirley’s gospel tune “Trilogy.”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UyUjoh3E3pw

Please feel free to add comments or memories of Cuzner and “The Dark Side.”

A shorter version of this article was published March 27, 2003 in OnMilwaukee.com

_______________

1 Listen here to Cuzner’s trademark show opening, Duke Ellington’s sublime “Solitude” with Cuzner piping up at about 3:30 in. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZhycM79gSYs#t=24

2. http://www.jsonline.com/entertainment/tvradio/having-the-pipes-just-part-of-making-magic-on-the-on-radio-lc39ch8-134871563.html

3 Once while I was listening I heard Cuzner say, “It’s the suggestion of Kevin Lynch that you drive safely tonight. You see, his life could depend on it. A message of safety from Kevin Lynch, and from WFMR, Milwaukee.” (He borrowed many friends’ names for that bit, often after talking to them on the phone.) Then he played something for me, unrequested. It was the title tune from Dave Holland’s Conference of the Birds — music a tad more cutting edge than he normally played, but he understood my taste perfectly and nailed it.

4 That first job as a DJ was memorable, especially the night I was on the air when breaking news came over the teletype that Marvin Gaye had been murdered. What an announcement to read on the air! WLUM is an urban station and the studio phone lines lit up like small souls suffering in an earthly purgatory.

5 When Cuzner emceed jazz concerts fans had an opportunity to see the latest of his trademark caps. He even wore one with his swimming trunks when he hosted his pool parties. It was more than vanity to cover his bald head; he was quite fair-skinned, a true nocturnal creature.

Alto saxophonist David Bixler. Courtesy myspace.com.

Alto saxophonist David Bixler. Courtesy myspace.com.

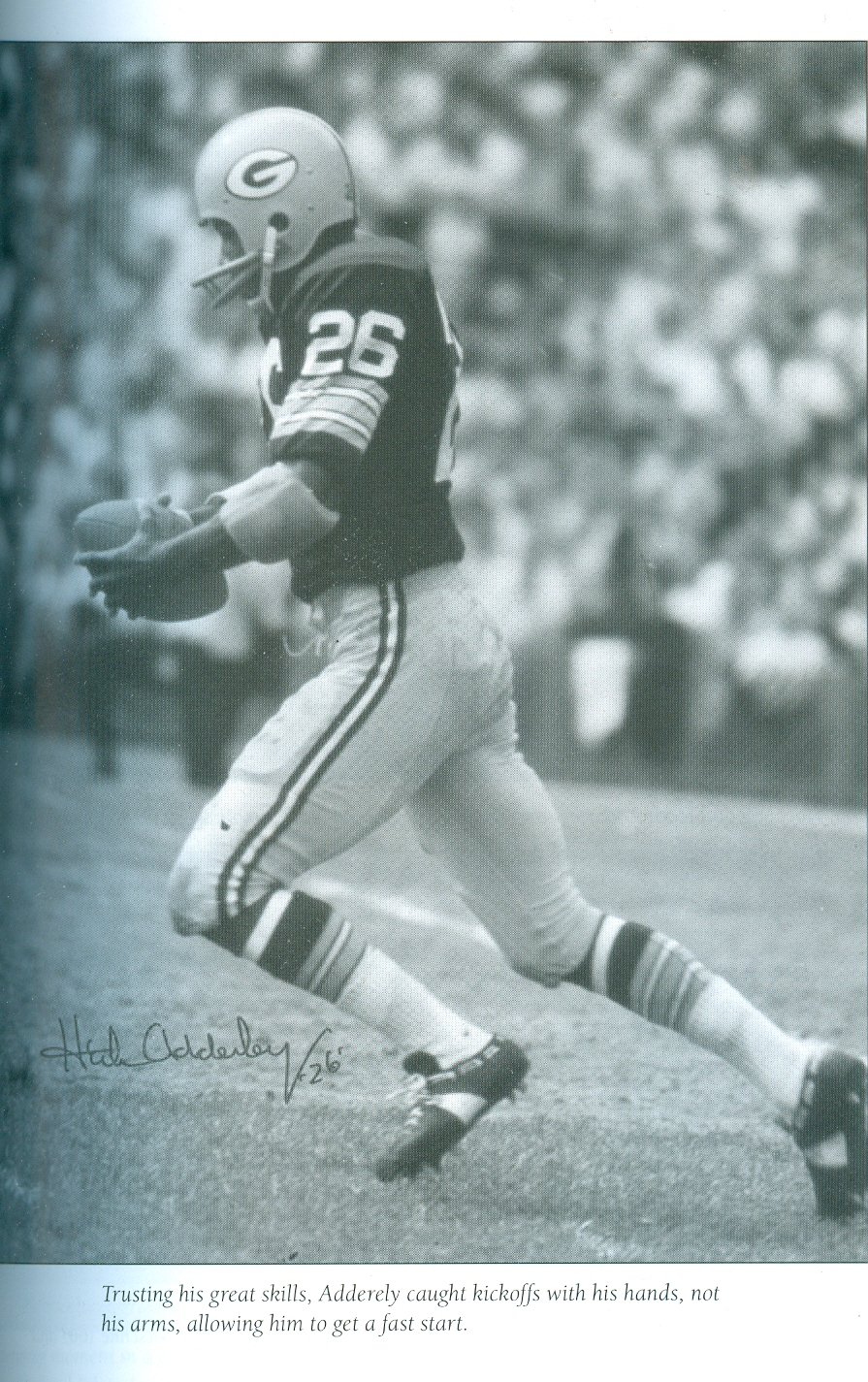

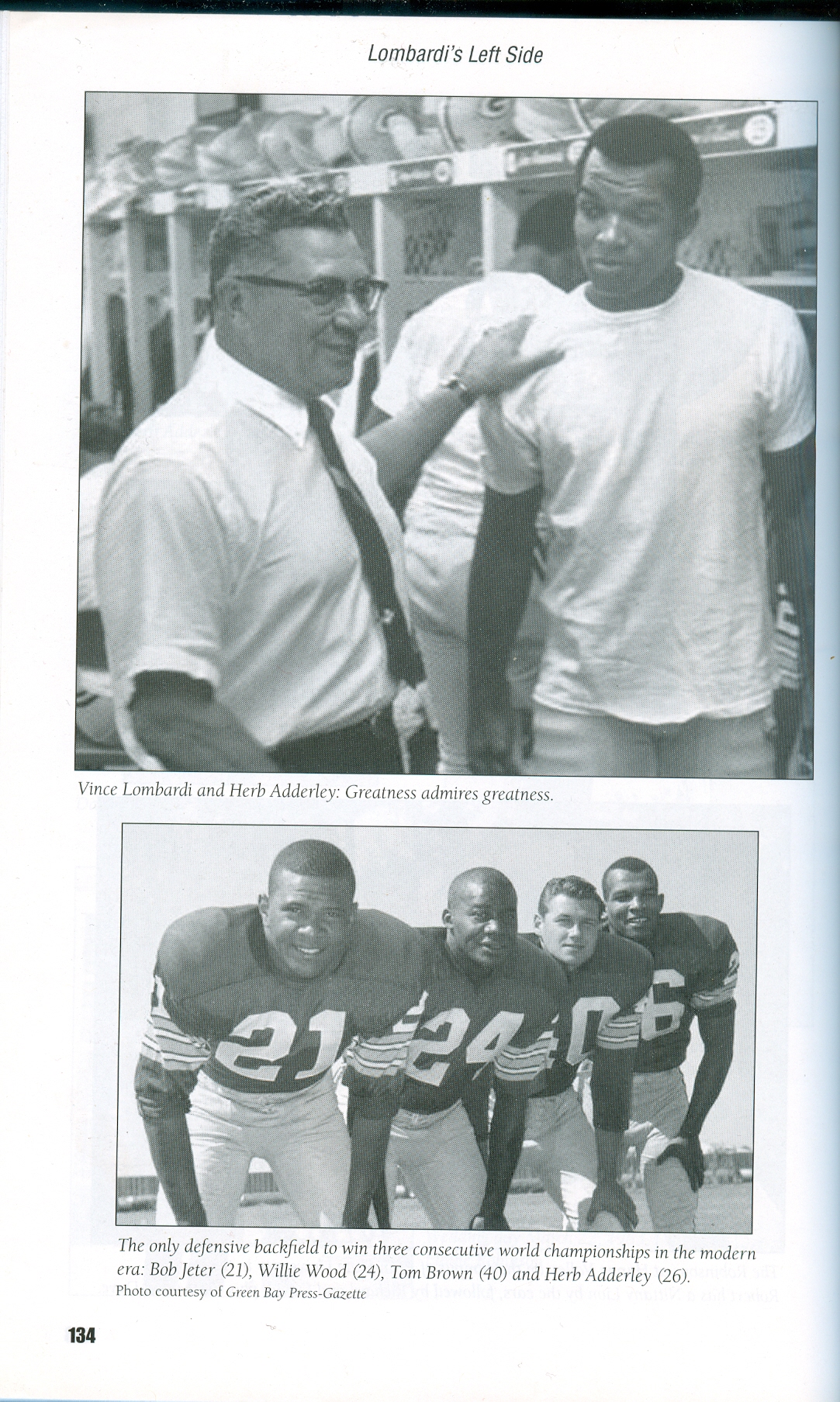

The great Packers coach Vince Lombardi had made Adderley the team’s first African-American first-round draft choice in 1961. He royally repaid Lombardi and Packer nation, over and over again. Some, like Pro Football Hall of Fame writer Ray Didinger say “Herb Adderley was the most complete NFL cornerback I ever saw. He could do everything. Some people call my radio show and say Dion Sanders is the best. Dion is in the Hall of Fame and deservedly so, but the next guy he hits will be the first. Herb could cover, hit, run and return kicks.”

The great Packers coach Vince Lombardi had made Adderley the team’s first African-American first-round draft choice in 1961. He royally repaid Lombardi and Packer nation, over and over again. Some, like Pro Football Hall of Fame writer Ray Didinger say “Herb Adderley was the most complete NFL cornerback I ever saw. He could do everything. Some people call my radio show and say Dion Sanders is the best. Dion is in the Hall of Fame and deservedly so, but the next guy he hits will be the first. Herb could cover, hit, run and return kicks.”

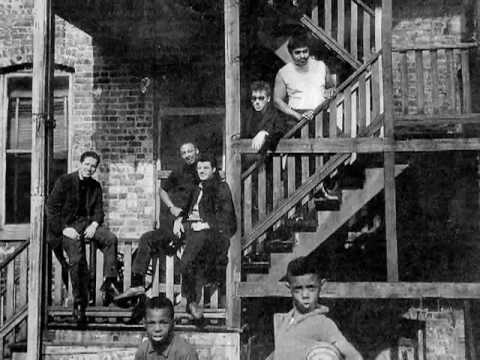

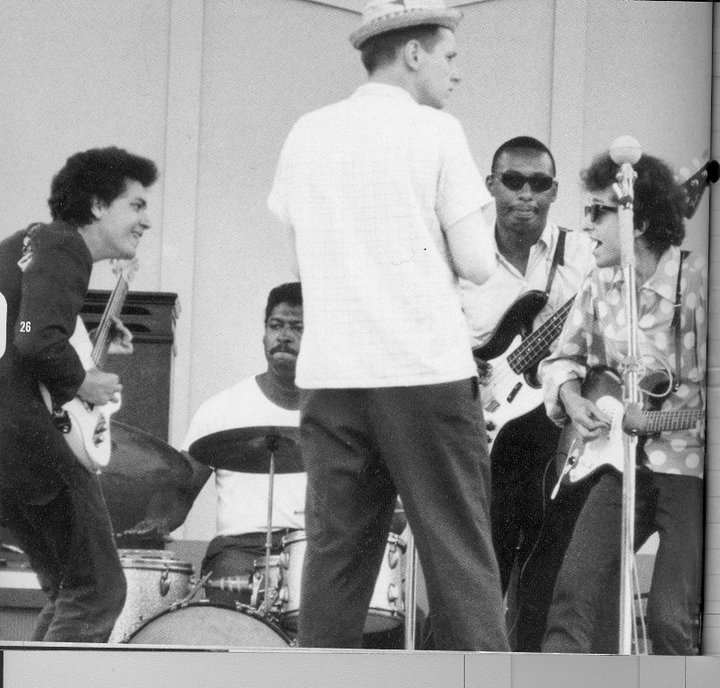

Bob Dylan shocked many listeners at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival by playing with an electric band including Michael Bloomfield (far left) on electric guitar and Bloomfield’s Paul Butterfield Blues Band mates, Sam Lay on drums and Jerome Arnold on bass. Courtesy Sony/Legacy

Bob Dylan shocked many listeners at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival by playing with an electric band including Michael Bloomfield (far left) on electric guitar and Bloomfield’s Paul Butterfield Blues Band mates, Sam Lay on drums and Jerome Arnold on bass. Courtesy Sony/Legacy

Norman Rockwell’s painted cover for “The Live Adventures of Michael Bloomfield and Al Kooper.” Courtesy popscreen.com

Norman Rockwell’s painted cover for “The Live Adventures of Michael Bloomfield and Al Kooper.” Courtesy popscreen.com

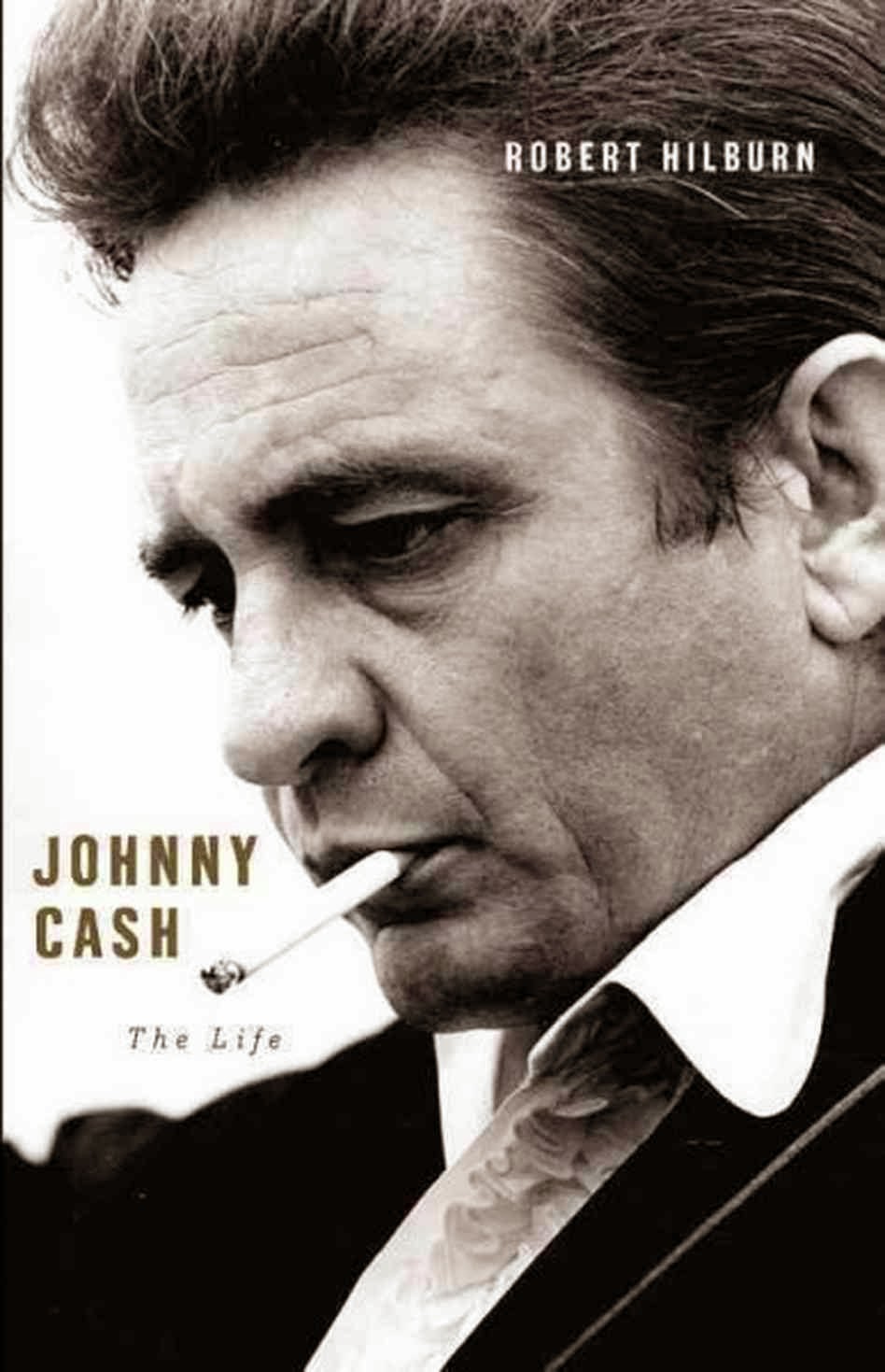

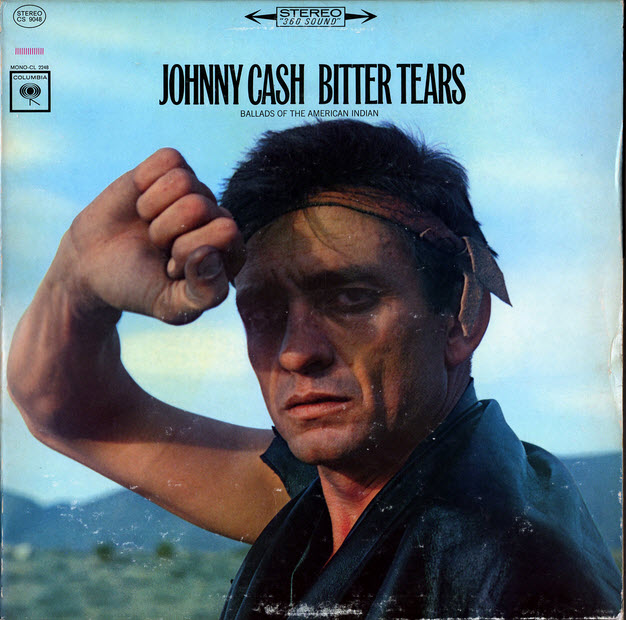

Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison in 1968. Courtesy experimentaltheology.blogspot.com

Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison in 1968. Courtesy experimentaltheology.blogspot.com

Courtesy bluenote.com

Courtesy bluenote.com

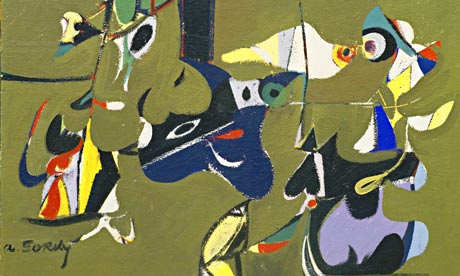

“Garden in Sochi,” Arshile Gorky, oil, 1940- 41. Courtesy studiointernational.com

“Garden in Sochi,” Arshile Gorky, oil, 1940- 41. Courtesy studiointernational.com “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” Arshile Gorky 1944: Courtesy wiki paintings.com

“The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” Arshile Gorky 1944: Courtesy wiki paintings.com “Portrait of the Artist with his Mother,” Arshile Gorky, 1926-29, Whitney Museum of American Art. Courtesy pinterest.com

“Portrait of the Artist with his Mother,” Arshile Gorky, 1926-29, Whitney Museum of American Art. Courtesy pinterest.com Another variation in Arshile Gorky’s “Garden in Sochi” series from 1943 nowritza.pwp.bluyonder.co.uk

Another variation in Arshile Gorky’s “Garden in Sochi” series from 1943 nowritza.pwp.bluyonder.co.uk A third “Garden in Sochi,” variation by Gorky, from the Museum of Modern Art. courtesy the Guardian.com

A third “Garden in Sochi,” variation by Gorky, from the Museum of Modern Art. courtesy the Guardian.com