Lombardi’s Left Side — Herb Adderley, Dave Robinson and Royce Boyles. Forward by Bill Cosby. $26.98, Ascend Books, www.ascendbooks.com

One foggy day in the early 1980s I walked down to the shore to take in the fresh, heavy atmosphere of Lake Michigan beside the Milwaukee Art Museum and War Memorial.

Then, out of the mist, a tall, agile man came jogging toward me. I quickly recognized the wide-set eyes and high, handsome cheekbones. It was Herb Adderley, probably my greatest athletic hero, like a vision, in the flesh. What struck me as he passed was his gliding, almost balletic lightness of foot, a rhythmic beauty in his stride, the proud bearing of his presence.

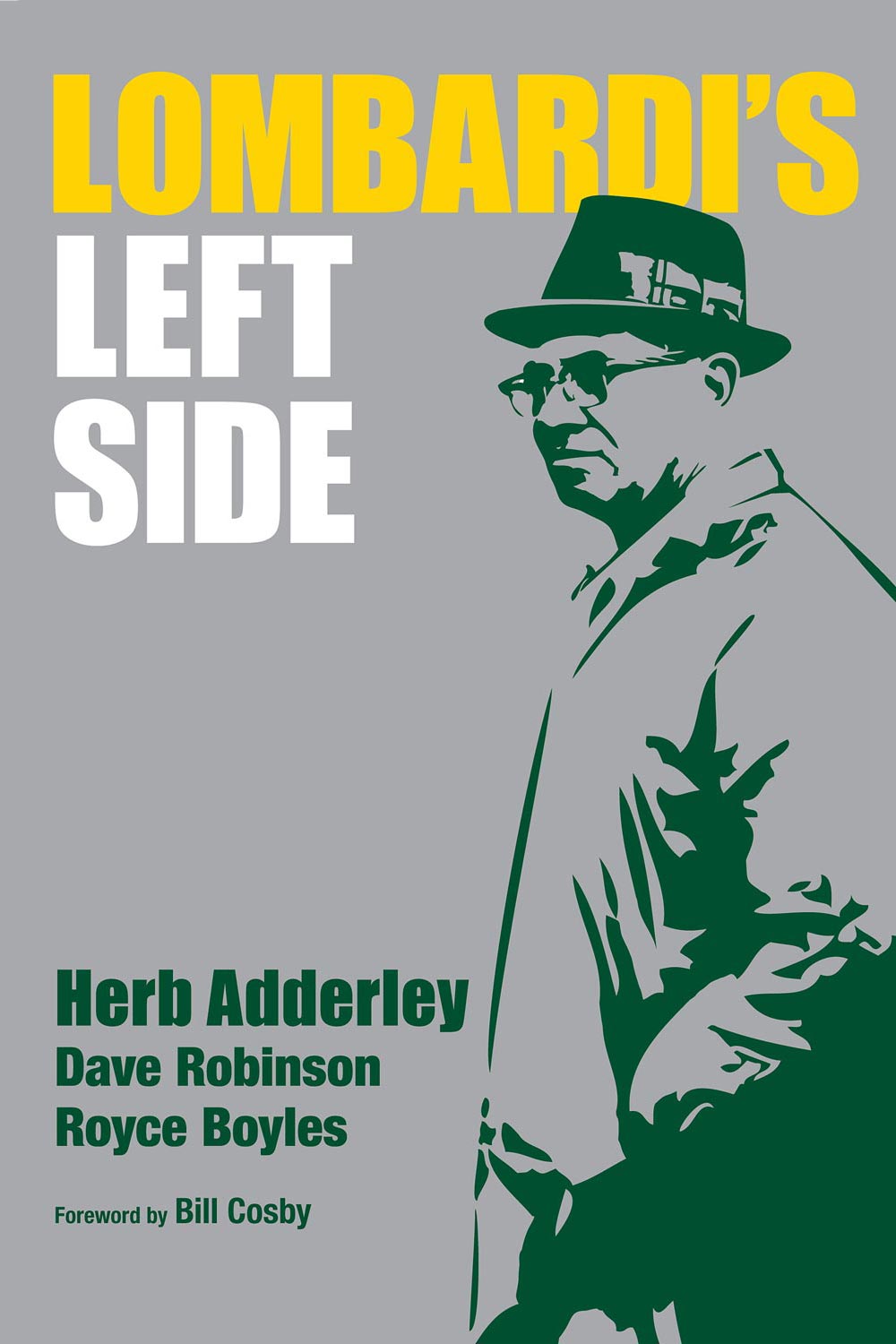

I turned and he disappeared, but fixed in my memory. I had always appreciated those physical qualities watching him play in his Hall of Fame career as a defensive back and kick returner for Green Bay Packers. A photo in Lombardi’s Left Side illustrates his artful way of catching long, end-over-end kickoffs – securely in his soft, bare hands rather than gathering it into his chest, so he could get a quicker start.

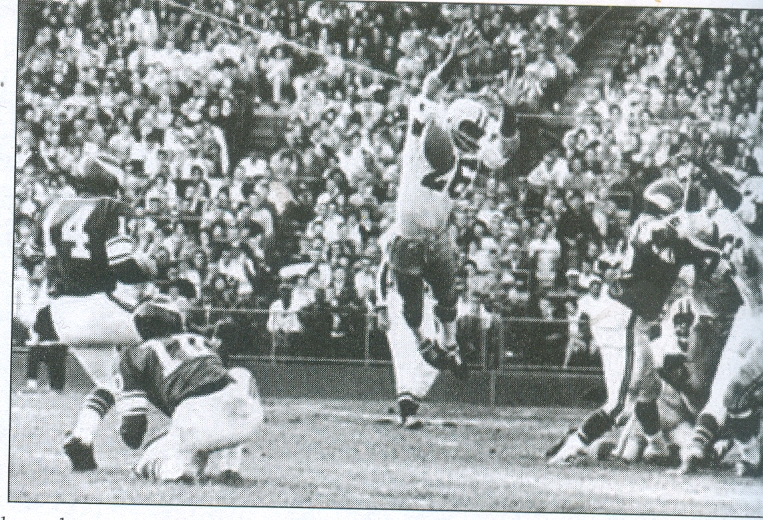

The great Packers coach Vince Lombardi had made Adderley the team’s first African-American first-round draft choice in 1961. He royally repaid Lombardi and Packer nation, over and over again. Some, like Pro Football Hall of Fame writer Ray Didinger say “Herb Adderley was the most complete NFL cornerback I ever saw. He could do everything. Some people call my radio show and say Dion Sanders is the best. Dion is in the Hall of Fame and deservedly so, but the next guy he hits will be the first. Herb could cover, hit, run and return kicks.”

The great Packers coach Vince Lombardi had made Adderley the team’s first African-American first-round draft choice in 1961. He royally repaid Lombardi and Packer nation, over and over again. Some, like Pro Football Hall of Fame writer Ray Didinger say “Herb Adderley was the most complete NFL cornerback I ever saw. He could do everything. Some people call my radio show and say Dion Sanders is the best. Dion is in the Hall of Fame and deservedly so, but the next guy he hits will be the first. Herb could cover, hit, run and return kicks.”

Adderley gave important things to America as well. I knew Herb was a superb athlete. Now, after reading the book he has co-written with teammate Dave Robinson – Lombardi’s top draft pick in 1963 — and author Royce Boyles, I know Herb is a great American. He fought for personal and social justice with all the intelligence, skill and tenacity he brought to his job as a prototype “shutdown” cornerback, ball-hawk and dangerous kick returner.

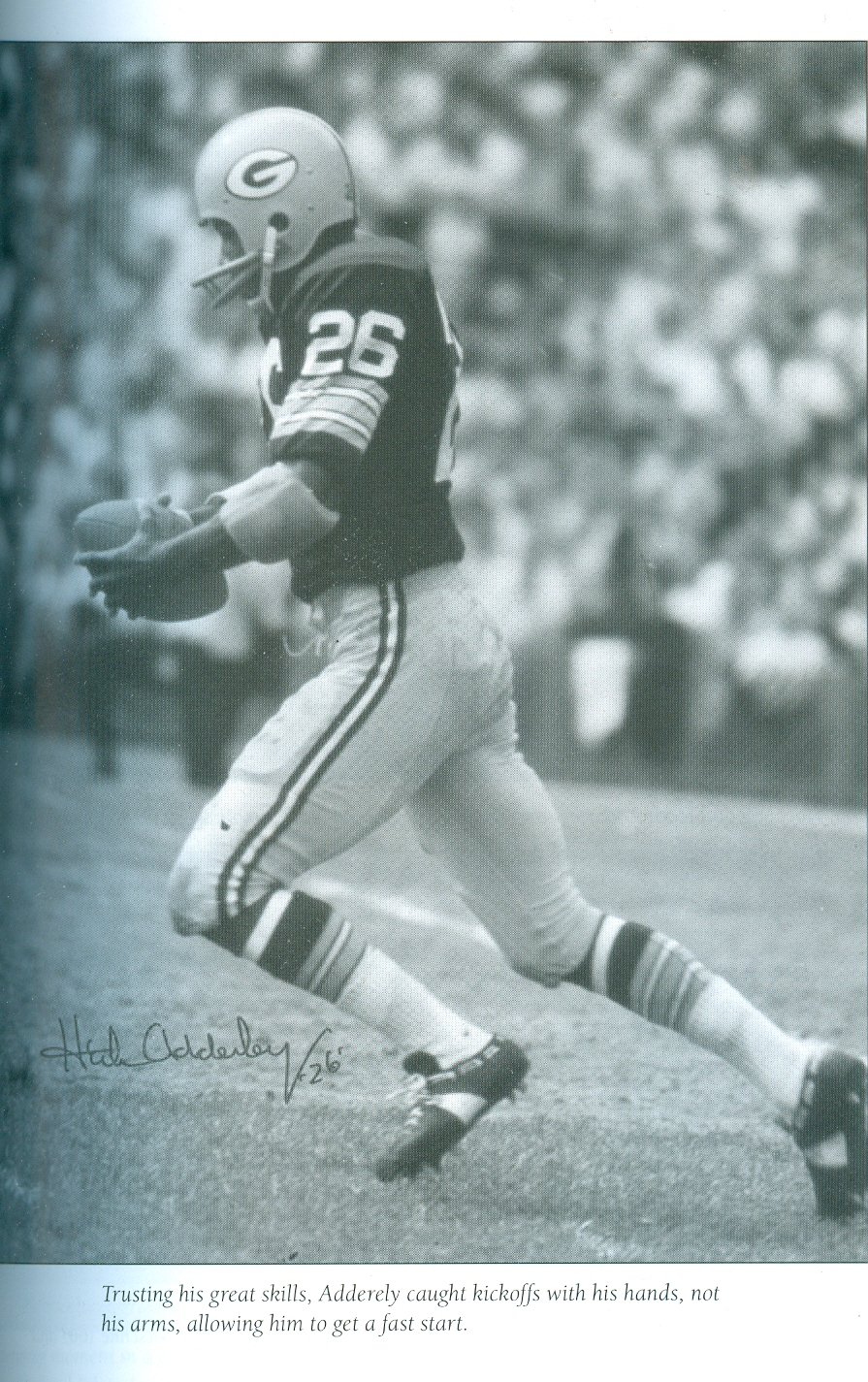

Herb Adderley displays his stunning athleticism with this field goal block. He was startled to realize he had penetrated so far that the ball hit him in the face. The Vikings coach objected that he was offside but apologized the next day when he saw the film.

Yes, it’s a sports book, but Lombardi’s Left Side distinguishes itself as the story of America’s sports culture and general society in the 1960s, and how that echoes down to the present.

I’ve read plenty about that football era, including Dave Mariness’ magisterial biography of Lombardi, When Pride Still Mattered. But there may be no book that has better highlighted and clarified the important role Lombardi played in advancing racial equality. I don’t think I’m overstating to suggest that Lombardi had a bit of Martin Luther King Jr. in him, and — tough guy that he was — perhaps even some of Malcolm X.

Adderley points out that, with his Italian descent, Lombardi would get a deep tan during the team’s late summer training camps and, at least once, experienced racial discrimination. Before a preseason game with the lily-white Redskins in North Carolina, a restaurant refused to seat him with his own blonde wife. When Lombardi told Washington’s acknowledged-racist owner George Marshall of the incident, Marshall laughed at at him, which eventually ended the two team’s longstanding preseason games, after Lombardi began scheduling the games every other year at high school stadiums. Lombardi’s point to Marshall was that racial advancement was more important than revenues — the sort of principled act that amazed and inspired Herb Adderley, he writes.

Lombardi understood the complex tenor of his times, the 1960s. As comedian Bill Cosby, who played on the same Philadelphia high school basketball team as Adderley, writes in his forward, “It happened during a chaotic time in America.” And the book “captures it beautifully.”

I think it’s a great book because there is much pain in that beauty — physical and psychological — especially regarding the ignorance and arrogance of racism, and the abuse of power, by both white and black men.

Coach Lombardi and two convention-defying African-American prize first-round draft choices had the right stuff to expose such societal and institutional flaws, and to work to change them, by example and by direct challenge.

The fast-reading story builds in dramatic tension, first over the course of the Lombardi era yet that saga is well-known, unfolding in the first great pro football dynasty in little Green Bay Wisconsin, population 80,000.

But the book’s edge comes from this story following the tumultuous racial undercurrents of the era. Though not many realized at the time, Lombardi opened the door for racial equality in pro football and the welcoming of diversity — especially towards African-Americans – which greatly increased the quality of play, despite the NFL’s ingrained mentality of white privilege, and several franchises (the Cowboys, Redskins and St. Louis Cardinals) that unflinchingly practiced racist policies, one of which Adderley would butt heads against directly.

Without flinching Lombardi drafted and traded for black football players in ratios as high as or higher than any team in the league, Royce writes. “He was not going to let any issue undermine team unity or keep them from getting excellent players, regardless of color.”

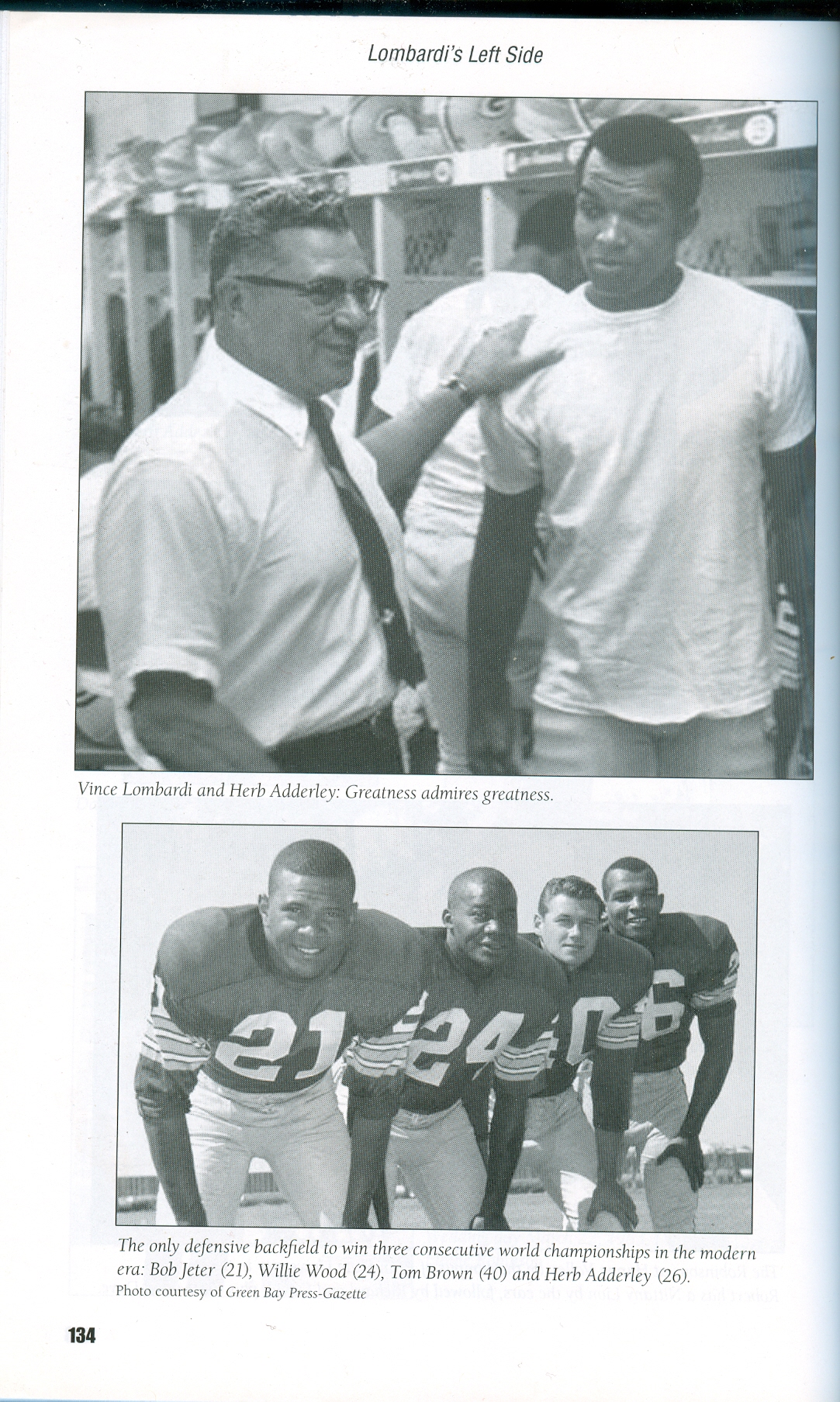

Lombardi’s was the first NFL team with an African-American starting linebacker (Robinson) and his dynastic defense included five great black players who contributed to the high standard of defense that won championships. Three comprised arguably the greatest left-side defense in pro football history — a key to defending against the naturally right-handed tendency of most offenses. These were end Willie Davis, linebacker Robinson and cornerback Adderley. 1 The other starting black defenders on those great teams were free safety Willie Wood, right corner Bob Jeter and right end Lionel Aldridge.

Tellingly the upstart expansion American Football League hired significantly more African-American players, and probably caught up with the senior league faster than many anticipated, because of that factor.

Remember, after the Packers won the first two dominating showdowns between the leagues, the Joe Namath-led New York Jets’ upset of the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III was one of the most startling reversals of destiny pro football had ever seen. The AFC team’s one-two punch at running back was a pair of black players, Matt Snell and Emerson Boozer. A third outstanding black Jet on that team played like Adderley — left cornerback Johnny Sample who picked off an Earl Morrall pass at the Jets’ 2-yard line in the first half which proved pivotal in the 16-7 Super Bowl victory.

Adderley’s career is studded with highlights, including 48 interceptions, nine touchdowns and an average of 25.7 yards per kickoff return (over 3,000 career kick return yards) and being selected for the Pro Football Hall of Fame All-1960s team. His seven interceptions returned for touchdowns was in an NFL record at the time. He also has the same career value by NFL weighted approximate value ranking (106, or tied for 76th place) as Charles Woodson, the greatest Packer defensive back of the Mike McCarthy coaching era. 2

They were strikingly similar players: tough tacklers who knew how to take a calculated risk for a game-changing play.

Adderley also nabbed the first interception return for a touchdown in Super Bowl history, in 1967 against the Oakland Raiders. It was Vince Lombardi’s last game as a Packer coach which was a great loss for not only the team but Adderley. Lombardi’s replacement, over-his-head assistant coach Phil Bengston, alienated much of the team, including Adderley who asked to be traded and was sent — intentionally he says — to racism-infested Dallas in 1969. Though the talented Cowboys fared better than Bengston’s Packers.Adderley went from one bad coach to another. Yes, Cowboy coach Tom Landry is a Texas legend, but he hated Adderley from the start, for being a member of the team that had defeated his Cowboys in consecutive playoff games, including the brain-freezing Ice Bowl in 1967.

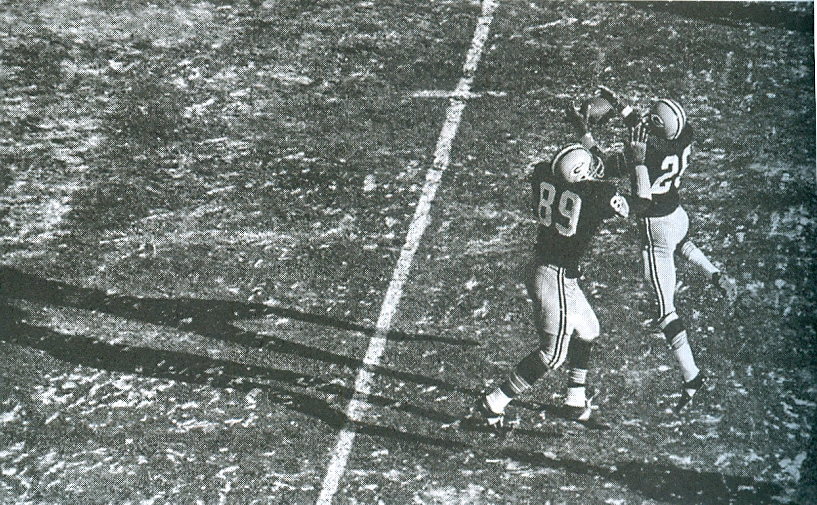

How many fans recall Herb Adderley’s interception (here with co-author Dave Robinson), or his fumble recovery in the 1967 Ice Bowl? * Herb’s heroics are frozen in the annals of history by the Ice Bowl’s iconic final drive.

Landry despised Adderley’s fashionable muttonchops and the cool composure that belied the guts to play several seasons with a lacerated bicep. Adderley proved an inspiring leader for the Cowboys, who’d been incapable of “getting over the hump,” and several players, such as star running back Calvin Hill say they never would’ve won their first Super Bowl in 1971 if not for Adderley’s leadership and inspiration. Cowboy defensive back Mel Renfro said, after a 38-0 thrashing by The St. Louis Cardinals “all hell broke loose from inside a number 26 jersey.”

“’What the hell is wrong with you? You guys act like a miserable bunch of losers,’” Adderley told the team. “The whole locker room got a wake-up call. Nobody had ever taken that approach before because Landry was so laid back as far as his emotions were concerned. Herb just tore into us and got our attention. He brought the Lombardi ambiance of ‘no crap.’ ‘Let’s get it done.’ He was very tough-minded.” 3

Green Bay’s ability to win close championship games was the hallmark of Lombardi’s greatness, and in big, tight games the Cowboys played well enough to lose: “they were in need of a heart transplant,” Royce writes.

Page by revealing page, the great Tom Landry shrinks into a very small man. He coached his team as if they were robots required to adhere to his complicated schemes. He ended up perversely benching Adderley — because he was using his intelligence, skills and instincts to make big plays, as Lombardi taught him to. Landry absurdly insisted that players rigidly follow his scheme, even if they gave up a touchdown. The book sheds light on some of the well-known photos of Landry grimacing in disgust after a loss.

Even worse, persistent racism infected the Cowboy clubhouse. On one occasion someone on the squad wrote the word “nigger” on top of the locker room bulletin board listing the NFL rushing leaders. An arrow led from the “n-word” to the name of the person atop the league leaders, the Cowboys’ own Calvin Hill. In another instance, the Cowboys’ former Olympic champion Bob Hayes was referred to as a “coon” in front of the entire team. “He pulled out a bone that looked like a chicken wishbone, referring to the term “coon bone.” Renfro recalls. Boyles notes that controversially slain Florida teen Trayvon Martin’s shooter allegedly referred to him as: a “f—ing coon.”

Adderley puts it bluntly: Tom Landry and Tex Schramm knew what was going on in Dallas and were part of it for not stopping it.”

In another instance, the two team leaders decided to keep a less talented white player and cut a more talented black player. “That racial tactic told me Landry didn’t put his best players on the field because of the color of their skin.” 4

The book’s final section is aptly climactic in its drama. It shows that the story has no race-baiting or politically correct agenda. It exposes African-American Gene Upshaw, head of the NFL Players Association as exploiting countless retired NFL players for what amounted to personal greed. It took someone is courageous and respected as Adderley to file a class-action lawsuit on behalf of the league’s retired players to recoup some of the millions being earned by video games, such as popular John Madden game, that used numerous retired players’ names and identities, without a penny of compensation. It’s a sad and heroic chapter in NFL history and another remarkable measure of a man as a transformative hero in the sport, both during and after his playing career.

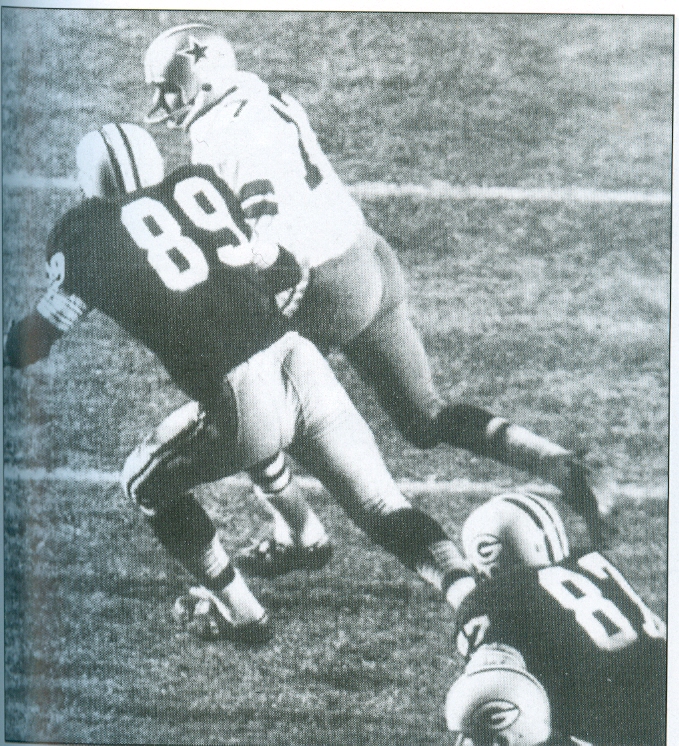

Dave Robinson (89) displayed his intelligence, size and athleticism in this climactic play of the 1966 NFL championship game, by forcing Cowboy quarterback Don Meredith to throw a game-ending interception in the end zone.

OK, as an Adderley-idolizing would-be cornerback who broke his leg in a 7th grade St. Robert team practice, I admit I haven’t done justice to Dave Robinson’s role in this story. (Full disclosure, a linebacker broke my leg.) Robinson’s huge play to sniff out a roll-out pass and force a championship-clinching Dallas interception might have been the most crucial athletic play of the Lombardi era. However, it is forever overshadowed by the heroics of the final drive of The Ice Bowl.

But Adderley clearly is the star of this eye-opening and deeply gratifying story, and his close friend Robinson seems to concede that.

________________

All photos copyright 2012, Lombardi’s Left Side, by Herb Adderley, Dave Robinson and Royce Boyles.

* Your faithful blogger watched the entire Ice Bowl again for this review. Herb Adderley’s greatest play of the game actually ended it. After Bart Starr’s famous quarterback-sneak touchdown, Dallas had several chances to score the winning touchdown. If completed, Don Meredith’s long pass with seven seconds left along the sideline would have stopped the clock in Packer territory and given him a chance to throw into the end zone and win the game. But Herb Adderley soared high into the air and knocked the ball out of bounds. With that, the Packers won an NFL championship for a record third consecutive year.

1 With Robinson’s February induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, all three members of “Lombardi’s left side” are now enshrined in Canton.

2 http://www.pro-football-reference.com/leaders/career_av_career.htm. Adderley’s NFL pick-six record would be surpassed by several players, but interestingly the two career leaders, Ron Woodson with 12 TD interceptions and ex-Packer Charles Woodson with 11, took 17 and 16 career years respectively to accumulate their totals. Adderley played only 12 years, and in his last year recorded no interceptions while riding the Cowboy bench, due to Tom Landry’s personal animosity toward him and his Lombardi-trained style. (Another ex-Packer, Darren Sharper, ties Woodson’s 11, but took 14 years. Sharper’s recent legal troubles suggest that Lombardi’s rare skill with character building would not be transmitted by osmosis into the Mike Holmgren era.)

3. Herb Adderley, Dave Robinson and Royce Boyles, Lombardi’s Left Side, Ascend Books, 2012 202

4. Ibid. 206

I am not a football fan, as you well know, Kevin. Despite that, I really enjoy reading this. Thanks for the link.

Ann

Must have done something right to get a non-football fan from Illinois to enjoy this. Smoke and mirrors, (slightly cracked?)