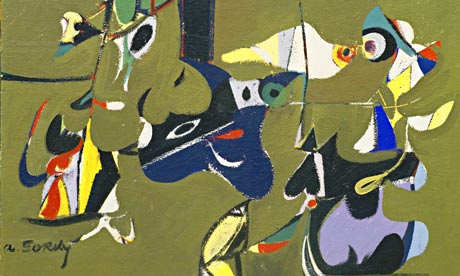

“Garden in Sochi,” Arshile Gorky, oil, 1940- 41. Courtesy studiointernational.com

“Garden in Sochi,” Arshile Gorky, oil, 1940- 41. Courtesy studiointernational.com

When I first heard that the winter Olympics would be held in Sochi, I thought it must be a beautiful place, endowed with sumptuous Russian landscapes. That’s because my primary association with the city is a series of paintings that Arshile Gorky (born, Vosdanig Adoian) created in 1940 through 1943, titled Garden in Sochi. So I present several digital reproductions of them with commentary inspired not only by these wonderful paintings but by two aspects of the Olympics that have grabbed me.

The first event was the performance at the Cultural Olympiad in Sochi by the Brian Lynch Quartet, led by the Grammy-winning, Milwaukee-raised trumpeter who has worked in the bands of many jazz greats including Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Horace Silver, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Phil Woods, and Eddie Palmieri. I recently wrote at length about Lynch’s recent recordings on another Culture Currents posting. But he played a time-honored role as an American cultural ambassador and he’s a product of both Nicolet High School and the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music, and the surprisingly vibrant jazz scene of Milwaukee in the late 1970s and early 1980’s.

I’m also celebrating the first gold medal ever won by America in ice dancing, thanks to the dazzlingly executed and sublime performance of Meryl Davis and Charlie White, a duet performance that few artistic athletes could equal, a testament to youthful dedication and vision.

So my subject is art and its resonances and, if they had asked me, the Cultural Olympiad would have borrowed one of Gorky’s Sochi paintings and used it as a motif in their promotional efforts for the Olympics. These beautiful works are both evocative of the region’s natural splendor while being distinctly modern in their abstract and dynamic lyricism. I now see certain athletic postures and gestures in these forms.

In the painting above, see the figure in the upper left, seemingly balancing on one leg and holding other limbs and bodily forms out in a complex and exuberant manner. Throughout the composition, the undulating forms can be seen as expanding and contracting muscles and tendons amid exertion and artful self control. Gorky surely never consciously intended such associations, but they seem valid now, because this is an art of allusion.

“By allusion the thing alluded to is both there and not there,” the critic Harold Rosenberg wrote of Gorky’s abstract work. “Allusion is the basis upon which painting could, step-by-step, dispense with depiction, without loss of meaning.” Thus, I contend the meaning could become multi-various, like the forms that arise in a garden each spring, related to forebears, yet each possessing unique character.

Allusion’s regenerative meaning was achieved through “emotional reference, evoked by color, shape, by movement…” Rosenberg wrote, which brings us back to physical art of movement, like ice dancing. 1

Rosenberg and a number of other observers also see the weight of history in Gorky’s work, as did the artist himself. His art testifies to the plight of the almost perennially oppressed Armenian people, an experience that many indigenous cultures of the sprawling regions of greater Russia endured as well, through that nation’s troubled, tragic and powerfully human history.

As a teenager, Gorky tried to flee with his mother and his sister Vartoosh to escape the Turkish genocide of Armenia. These children and Lady Shushanik were forced on the 100-mile “death march” of 1915 to the frontier of Caucasian Armenia. The mother grew sick as she refused most food and water that her children frantically searched for, because she cared about their health and welfare over her own. According to Vartoosh’s son Karlen Mooradian, “In a frenzied effort to obtain food money, Gorky, aided by Vartoosh, carved traditional Armenian women’s combs from ox and bull antlers acquired from street vendors, and tried to sell them.” 2 This experience may be a genesis of one of his most famous paintings, The Liver is the Cock’s Comb which, though a later and more complex work, actually contains compositional parallels to the Garden in Sochi series.  “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” Arshile Gorky 1944: Courtesy wiki paintings.com

“The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” Arshile Gorky 1944: Courtesy wiki paintings.com

The Adoian family had hoped to reach the Georgian capital, about 100 miles to the north and toward Sochi. But they never got beyond Yerevan, because the mother became critically ill from malnutrition and refused to leave the soil of Armenia.

After the government refused to allow the children to place their mother in a hospital for homeless genocide orphans, the brother and sister tried to care for her in an old “war-torn room in a dusty abandoned structure whose inhabitants had been killed,” wrote Mooradian. The roof leaked when the snow began melting near the end of the winter of 1919, and each morning before leaving, Arshile and Vartoosh “lifted up their mother and placed her on the window ledge to lessen the chance of forgetting wet.”

On March 20th of that spring, 39-year-old Lady Shushanik collapsed in the arms of her children — dead of starvation and of the genocide that killed two million Armenians, or three-quarters of the nation. The Turks were also warring with Russia, so Armenia became a great battlefield. At the time, Vartoosh was 13 and Gorky was nearly 15, and beginning to develop strong artistic sensibilities. 3

Vartoosh says that his mother taught her brother “the poetry of Van’s nature. Of the sea, plants, animals, the mountains and valleys, the earth and clouds. She was the port Queen. Gorky never forgot what she had taught him.’ Someday,’ he told me, ‘my paintings of mother will make her live forever.” 4  “Portrait of the Artist with his Mother,” Arshile Gorky, 1926-29, Whitney Museum of American Art. Courtesy pinterest.com

“Portrait of the Artist with his Mother,” Arshile Gorky, 1926-29, Whitney Museum of American Art. Courtesy pinterest.com

And a couple of paintings and drawings of their beautiful mother are among Gorky’s most famous works of art and show his mastery of traditional and modernist artistic portraiture. Gorky wrote in a 1943 letter that he should have really titled the Sochi series Garden in Khorkom, for a Gorky family garden in Armenia. Nevertheless, one can imagine that he envisioned this garden in Sochi as signifying the family’s deliverance — Sochi was the closest city in Russia that would not be under Turkish influence. In the letter, he referred to the family garden, perhaps to gratify family members: “In that series I have, for example, depicted most prominently the beautiful Armenian slippers father and I used to wear, the ones we purchased in Armenia’s Van from the Armenian artists when uncle Grikor and I rode there by horse.”

Another variation in Arshile Gorky’s “Garden in Sochi” series from 1943 nowritza.pwp.bluyonder.co.uk

Another variation in Arshile Gorky’s “Garden in Sochi” series from 1943 nowritza.pwp.bluyonder.co.uk

The artist also depicts “my translations of mother’s soft Armenian butter churn, that pearl in the crown of our hard-working village women. How vividly those days imprint themselves in my heart.” (Note: There is controversy over some of the Gorky letters published by the late Mooradian, whom some art scholars accuse of forging or changing some of his uncle’s letters.) 5

This evocation also reveals Gorky’s deep affinity for Armenia’s ancient and widely influential culture, what Mooradian extensively argued is Gorky’s predominant “hylozoist” outlook. One can begin to sense the dark and deeply personal historical complexities of expression in Gorky’s inherently lyrical abstractions.

Rosenberg saw Gorky’s as work as less biographical while acknowledging their historical heft. Gorky was an extremely erudite amateur historian of art and his early work clearly claimed Picasso and Cézanne as influences. Joan Miro’s influence is also evident underlying some of the Armenian artist’s fanciful forms and compositions.

Gorky’s went on to become among the greatest of the first generation of American abstract expressionists, which included many immigrants who fled war-ravaged Europe, Russia and the Middle East. Willem de Kooning, who once shared a studio with Gorky, commented: “He knew lots more about painting and art—he just knew it by nature—things I was supposed to know and feel and understand. . . . He had an extraordinary gift for hitting the nail on the head.” 6

So, given Arshile Gorky’s sense of art’s historical threads of development, Rosenberg saw the abstract art as products of a program “experimental research.” : “Each of the different versions garden in Sochi is a rap upon a different stylistic door to the future, and a disappointed turning away when no answer comes.

“We can see today that the 1940s Garden was a sufficient opening through which unexplored regions might have been reached. Unfortunately, history, when it does supply answers, never labels them as such.” 7

So the Sochi paintings’ echoes of artistic allusion resonate with the dark clouds of historical experience, and yet remain alive with the inspiring energy of springtime — and of indomitable human achievement.

To make them a world community experience, pan-cultural events like the Olympics need all the historical resonance they can get.

A third “Garden in Sochi,” variation by Gorky, from the Museum of Modern Art. courtesy the Guardian.com

A third “Garden in Sochi,” variation by Gorky, from the Museum of Modern Art. courtesy the Guardian.com

____________________________

1. Harold Rosenberg, Arshile Gorky: the Man, the Time, the Idea, , Horizon, 1962, 55-56

2 Karlen Mooradian, Arshile Gorky Adoian, , Gilgamesh, 1978,143

3. Ibid. 147-48

4. Ibid. 148

5. Ibid. 277 (NOTE: Arshile Gorky Adoian and sister Vartoosh escaped to America in 1920, a story recounted in a previous Culture Currents posting https://kevernacular.com/?p=1848 which further details Gorky’s artistic development and relationship to his mother, and my visit with Vartoosh Adoian Mooradian and Karlen Mooradian. I was fortunate to meet them in Chicago, after they noticed a review I wrote of the 1981 Gorky retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum.

6. Melissa Kerr, Gorky Life Chronology, The Arshile Gorky Foundation http://arshilegorkyfoundation.org/gorkys-life/chronology

7. Rosenberg, 82-83.

Kevin, Big thank you for this~

Washing studio floor!

Dale

Gee, Dale, if the post at all helped spur you to wash the studio floor I can finally answer all the naysayers. My writing finally served a practical purpose! I bet your wet floor looks pretty interesting too.

Thanks for reading and responding, KL

Wow, Kevin! Such a beautifully written, detailed interpretation of art, complemented by a powerful historical framework with a story I did not previously know.

Thank you for giving me such lovely opportunities to read and grow.

Ann

Ann,

I’m so happy the Gorky post somehow made for good late-night reading. As good as a cup of warm, lavender tea?