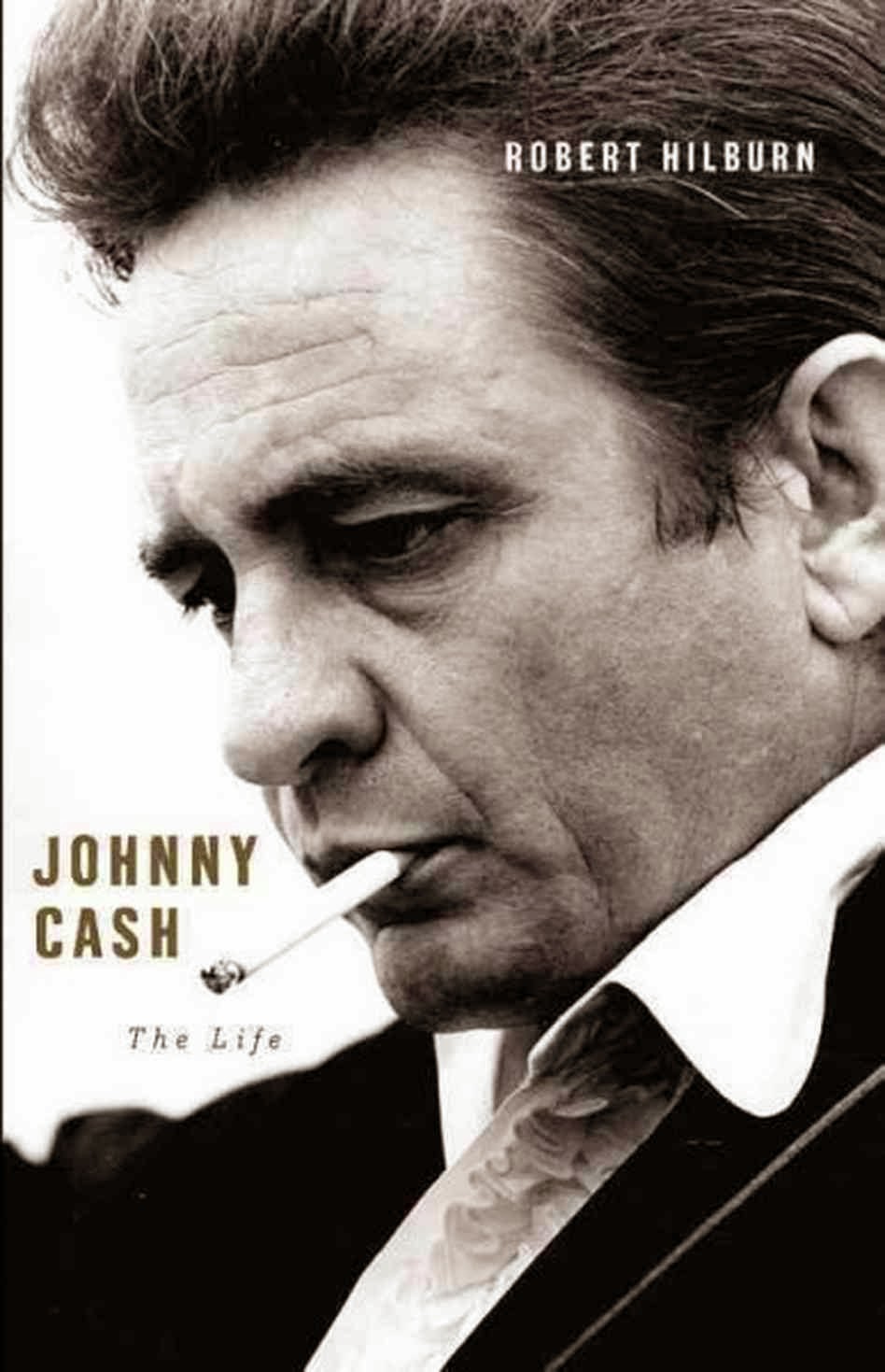

Johnny Cash: The Life by Robert Hilburn (Little, Brown) $32 679 pages

The steely quaver in Johnny Cash’s voice seemed to ring out of the blackest, most-bedeviled corner of the male American psyche. It conveyed the resolute self-assurance of a guy you could count on standing up for the little guy — if not for showing up for a concert date. But to know the man’s life story is to understand all the fault lines cracking the foundation of that heroic American voice and vision.

His John Wayne-esque musicality never sounded slight, even for a few goofy if tough-minded songs like “A Boy named Sue,” which became an improbable hit. It tempered his voice’s natural gravity while revealing a slipstream of humor in a man who often suffered miserably through his life.

Cash hauled his deep-bottomed baritone like a riverboat skipper through a sort of upstream river odyssey, which often felt like the challenging stuff of a novelist. Cash found an outlet to trace his sense of humanity’s tragic arc in his pioneering concept albums. These he dedicated to the truth and poetic mythology of America’s varied strains of “huddled masses,” as they dispersed and faced their often harsh destiny.

These albums were a central aspect of an artistic ambition unmatched in country music history. In many circles he would eventually be proclaimed as the greatest artist in the history of the genre, finally surpassing Hank Williams. He would care for other people’s souls much more than his own, while struggling mightily to control the day-to-day impulses that a fast-rising and descending superstar faced with life on the road.

That’s where the wide-ranging pathos and, yes, the juiciness of this biography arises.

Hilburn is frank without indulging voyeurism on a man with a large appetite for life.

He seems to have been through much of it with Cash, albeit with the proper journalistic distance. He is touted as the only journalist to have witnessed Cash’s legendary concert at Folsom Prison (a photo in the book verifies his presence there, actually standing beside Cash.)

So Hilburn manages the delicate balance of opportunity that a posthumous work provides while treading carefully through Cash’s large, extended natural and musical family, and among the profusion of memoirs they produced, along with Cash’s own two autobiographies. In Hilburn’s picaresque scenario, Johnny Cash’s complicated life of drug addiction, unpredictable behavior and infidelity puts a great onus on him as a performer, artist and as a man.

But Lordy, we feel Cash’s own suffering and the travails of those closest to him, especially the four daughters he sired with his first wife Vivian, whose domestic ways perhaps doomed her prospects as a lifelong mate of such a driven and charismatic performing artist. The admiring females came a-callin’, as did the siren song of drugs, to help ease the pressures of the road. He stayed hooked on amphetamines fitfully through much of his career and a number of crazy scenes resulted, including driving his second wife June Carter’s Cadillac into a telephone pole and breaking his nose and knocking out four front teeth. Or accidentally helping ignite a 500-acre National Park forest fire that resulted in 53 dead condors.

Yes, Cash fell down, down, down, into a ring of fire. But he improbably managed to become the most popular American recording artist of the late ’60s and early ’70s, by the force of artistic will and unshakable human and spiritual values. In 1969, he help Bob Dylan perform a transcendent “Girl from the North Country” on the iconic folk-rock singer’s country album Nashville Skyline. Cash’s Grammy-winning liner notes to the album may be the most poetic evocation of Dylan’s genius ever penned. A sampling of the notes:

This man can rhyme the tick of time

the edge of pain, the what of sane

And comprehend the good in men,

Can feel the hate of fight,

the love of right

And the creep of blight

at the speed of light

The pain of dawn,

the gone of gone

the end of friend,

the end of end… 1

That year, Cash sold more records (6 million) than anyone had in a year. This would lead to his extraordinarily pioneering television variety show.

What also led to that point was the path he took championing America’s most embattled and forsaken peoples. He’s best known for the often blistering and virtually unprecedented prison albums at Folsom and San Quentin (he’d served jail time for a drug bust in El Paso). In the slightly chaotic San Quentin performance, you get the uncanny feeling that Cash has managed a shift of moral grounding — and that the prisoners have covertly taken over the prison, akin to Melville’s Benito Cereno, and righteously so.

Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison in 1968. Courtesy experimentaltheology.blogspot.com

Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison in 1968. Courtesy experimentaltheology.blogspot.com

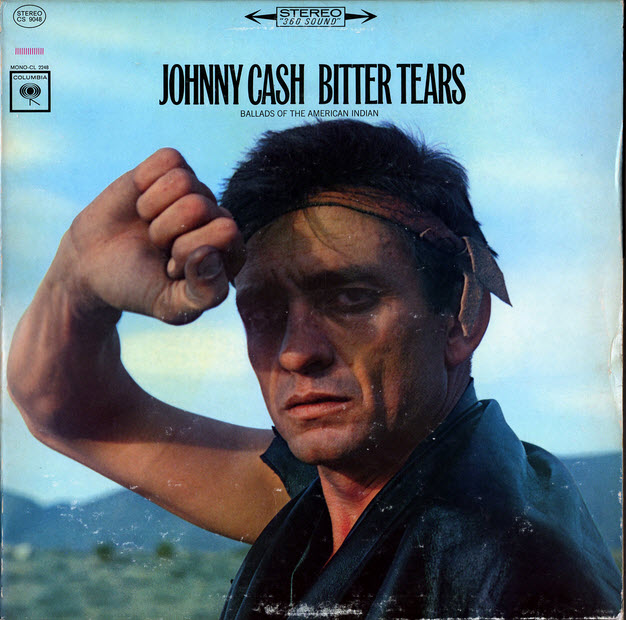

After those, his most famous humane interest was for the Native American, whom he identified with deeply and realized that their cause had received short shrift during the civil rights movement of the ’60s. The cover of his album Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian shows him dressed unironically as an Indian. The various paeans and story-songs include included a savage portrait of General Gorge Custer — then still depicted in school textbooks as a hero — for his slaughter of Native Americans.

Then there’s the unforgettable “Ballad of Ira Hayes.” Hayes was a Pima Indian, one of six Marines in the historic photo of the flag raising on Iwo Jima during World War II, perhaps the most celebrated image of the war. Hayes struggled with all the attention and returned to his native Arizona and tried to lead a normal life. The iconic photo’s fame wouldn’t let him be. He felt unworthy — other soldiers had given their lives in the battle. “He sank deeper into alcoholism was and arrested 52 times for public drunkenness before he was found dead in an abandoned adobe hut,” Hilburn reports.

The LP cover to Cash’s “Bitter Tears,” also reissued as a CD. Photo courtesy joannasvision.com

Cash planned the song as his set’s centerpiece at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival, run by George Wein, who founded the celebrated Newport Jazz Festival and was widely admired for artistic integrity more than commercial values.

It was a historic event, with the first appearance of Bob Dylan the festival broke its attendance record with 70,000 paid customers. But the date epitomizes Cash’s challenges and triumphs. His mounting nerves addled by drugs, he missed his plane flight to Rhode Island and was re-scheduled for the end of the festival.

“He didn’t look good. With his drawn face and his unfocused manner, he resembled a man on a wanted poster,” Hilburn recalls.

Nevertheless, “Cash sang (“Ira Hayes”) with a commitment and purpose that transformed his set. It was the moment he had been waiting for. This was his message for Newport. This was who he was and what he believed…’Ira Hayes’ was a revelation for an audience that knew Cash chiefly for his hits.” 2

What Johnny Cash brings to his performance as a singer-songwriter, and as a man living a life he struggled with, makes him so compelling. He seemed to exert no effort to impress with stylistic manner or pretense. He rarely strayed far from the spare boom-chicka-boom rhythmic groove of his longtime backup band the Tennessee Three. But he knew how to exercise poetic license.

On The Johnny Cash Show he sang “The Man in Black” and explained that he wore the funereal color for all the struggling and bereft humans in America, though some saw this explanation as insincere, as he’d worn black for many years.

It didn’t matter — he made his point brilliantly. That sense of artistic license also meant he set a broad definition of what valuable music constitutes. His TV program bridged the cultural gap between traditional country and the emerging pop counterculture, besides great country artists he also presented Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Derek and the Dominoes, Stevie Wonder, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Linda Ronstadt, Kris Kristofferson and, showing his sense of history, Louis Armstrong, wherein Cash and Satchmo re-created Armstrong’s recording of “Blue Yodel #8” with Cash’s country music role model Jimmie Rogers.

At least one of the daughters inherited much of her father’s gift. So we’re fortunate that Roseanne Cash’s body of work is simpatico and complementary to her father’s. Neither here nor in her wonderful memoir Composed, does as Roseanne let dad off the hook. And yet, we come to know how much he finally redeemed himself in her eyes.

Daughter Roseanne and Johnny Cash, late in his life. Courtesy hqwallbase.com

Besides personal reconciliation with Roseanne, he spoke to her, and to millions, through extraordinary art, such as the song “Hurt,” one of the high points of the album The Man Comes Around, part of an unlikely ongoing collaboration between Cash and rock producer Rick Rubin which produced several magnificent autumnal career albums. Cash laid claim of a new medium brilliantly with his music video of “Hurt,” a lacerating testament to moral suffering written by Trent Reznor, lead man with Nine Inch Nails.

With wife June — just diagnosed with cancer — looking on, the Grammy-winning “Hurt” depicts Cash shouldering a tremendous burden with a sort of naked grace.

Amid artifacts of a lifetime, Cash sings: “I hurt myself today/to see if I still feel…Everyone I know goes away/ in the end/ and you could have it all/ my Empire of dirt/ I will let you down/ I will make you hurt.”

Here’s the video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SmVAWKfJ4Go&feature=kp

Roseanne saw it this way: “Dad showed me the video in his office at the house and I cried all the way through it. I told him, ‘You have to put it out. It’s so unflinching and brave and that’s what you are.’ I was tremendously proud of him. I thought it was enormously courageous. It was a work of art, excruciatingly truthful. I thought, ‘How could that be wrong in a way?'” 3

Perhaps that is the best way to view Cash’s career and his deeply troubled life. He did most everything, in this story, for the sake of his art, in all its history-laden beauty and excruciating truth.

Hilburn unflinchingly and humanely follows the long, rocky road to its end. And yet, let Kris Kristofferson have the last biographical word, here in his comment in Rolling Stone’s list of the 100 greatest artists of all time. “Johnny Cash was a biblical character. Like some old preacher, one of those dangerous old wild ones. He was like a hero you’d see in a Western. He was a giant. And he never lost that stature.” 4

________________

* Ira Hayes’ story is also dramatized in the Clint Eastwood film Flags of our Fathers.

1. from liner notes by Johnny Cash for the album Nashville Skyline by Bob Dylan, 1969 Columbia Records, reissued 2003 Sony Music Entertainment, Inc.

2.Johnny Cash: The Life, by Robert Hilburn, Little, Brown, 2013. p 260-61

2. Ibid, p. 603

I know my nephew will enjoy learning about Johnny Cash by reading this passionate review, Kevin.

Ann

Thanks Ann, I love the opportunity to try to answer his curious adolescent question, “Who is Johnny Cash?”